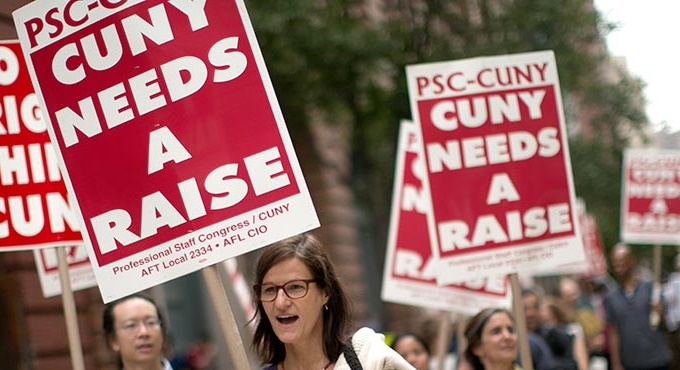

Photo by Dave Sanders / NYSUT United

When I began teaching as an adjunct lecturer in 2001, I was a first-year graduate student in English at the CUNY Graduate Center. I was 29 years old, but I had no previous teaching experience, had received no training, knew little about designing a course, and knew almost nothing about how students learn. I had arrived fresh from Amherst, Massachusetts only about ten days prior.

There I was, on a Saturday morning in early September, standing in front of a class of undergraduate freshman at Lehman College in the Bronx. My composition students that semester were almost exclusively working class people of color, and several of them were recently-arrived immigrants, many of whom were effectively still learning to speak and write in English. The challenge before me was enormous. I had been tasked with helping these 30 or so new students learn how to read critically and how to write clearly and persuasively. For this, I was paid about $2,400 for four month’s work, enough after taxes to cover little more than half of my rent. Today that same adjunct, tasked with those same responsibilities, would receive about $3,200 — amounting to just over a 30 percent increase spread over 16 years (far below the rate of inflation for the same period).

While many workers across the country and the globe have been faced with similarly falling wages, the situation at CUNY is the product of an intentional and ongoing series of economic assaults on American public colleges and universities — a practice that has been made possible, in part, by the continued and expanded use and abuse of adjunct instructors. This economic attack, and the way that university administrations have responded to it, has effectively devalued the practice of teaching and dramatically altered the nature of public higher education in America.

But academics and their unions are wise to the ways that the exploitation of adjuncts hurts faculty and students, and they have begun to fight back. At CUNY, the Professional Staff Congress (PSC), which represents about 25,000 faculty and staff, has approved a historic set of contract demands that directly confront the continued exploitation of adjunct faculty. If won, these demands have the potential to fundamentally transform the university and could set a precedent for other faculty unions at other colleges and universities. However, the PSC’s track record when it comes to addressing the fundamental inequalities between adjuncts and full time faculty is mixed at best — indeed, under the current union leadership, pay inequality for adjuncts has actually increased — and winning a truly transformative contract will require a rank and file who are willing to fight, even when the leadership won’t.

An Injury to One is an Injury to All

Like most other public colleges and universities, CUNY has, over the last thirty years, been subject to a series of state and city budget cuts that have drastically reduced funding for students and decimated the university’s finances. Since the 1980s, city and state investment in the university has fallen steadily, and in 2008-2015 alone, per-student state funding for CUNY’s senior colleges fell by 17 percent while city funding to the community colleges dropped by 13 percent (relative to inflation).

These cuts track the bigger nationwide trend of disinvestment in public universities and programs that has been one of the hallmarks of neoliberal capitalism. While students and faculty have pushed back against this trend, holding mass rallies and protests against tuition hikes and budget cuts, the CUNY administration and the politically-appointed CUNY Board of Trustees (BOT), which takes its marching orders from the mayor and governor, have been largely complicit, rarely questioning the logic of austerity and vowing always to do more with less. Though the consequences of this collusion are many, including a dramatic rise in tuition and largely stagnant wages for faculty and staff, one of the most insidious outcomes of this decades-long assault on CUNY has been a dramatic expansion of the exploitation of cheap, flexible, and — from the university’s perspective at least — ultimately disposable adjunct labor, a practice that has eroded the quality of instruction, shrunk the degree of self-governance, and weakened the power of the faculty and staff union.

This continued use of adjunct lecturers in place of more expensive, full-time or tenure-line faculty has effectively allowed the university to absorb these cuts with little to no administrative resistance. This practice has, in turn, only encouraged more cuts, fueled the ongoing budget crisis at the university, and driven up tuition; all while subjecting a whole generation of often dedicated, experienced, and hard-working lecturers to a career of low pay, few benefits, no job security, and little respect. Indeed, these faculty members, who now teach more than 53% of the courses at CUNY, receive only a fraction of the wages and often none of the benefits that their full time colleagues receive.

But the exploitation of adjuncts isn’t only a question of fairness or wages. It’s a form of structural inequality that the state, the university, and the BOT have ruthlessly used to their benefit for decades, often to divide faculty and drive a wedge between faculty and students. While full-time faculty are paid to participate in the governance of the university, building relationships with other faculty and staff in the process, adjuncts are neither paid nor encouraged to take part in the day to day decision making of the colleges where they work. While full-time faculty have time to attend and participate in union meetings and rallies, adjuncts often teach on many campuses at once and rarely have the time or inclination to get involved with the union. Indeed, even engaged adjunct activists frequently lament their inability to be more active precisely because they are so overworked. This means not only that the full-time faculty must shoulder the burden of this work, but also that the voice and power of the entire faculty within the university is significantly weakened.

This weakening of faculty governance and agency has given even more power to the growing ranks of administrators determined to make public higher education a mirror of the corporate society it has increasingly been forced to serve. Using corporate-driven curriculum initiatives like Pathways — which are designed to churn out graduates more quickly, usually at the detriment of actual learning — to disruptive “innovations” that treat students as consumers and institutions as mere service providers, administrators have been given carte blanche to make the university the handmaiden of neoliberalism and its attendant ideologies, often with the help of corporate think tanks like the Lumina and Bill and Melinda Gates foundations,.

Despite this, or perhaps because of it, many faculty and staff unions like PSC CUNY are pushing back against this assault on their members and going on the offensive.

A Transformational Demand

On November 9, the Delegate Assembly of the PSC CUNY (composed of more than a hundred elected members from more than a dozen different campuses) unanimously approved a set of contract priorities that includes, among other ambitious demands, a historic call for a minimum rate of $7,000 per course for CUNY adjuncts. CUNY adjuncts currently make a minimum of only $3,200 per course, so this demand, if won, would mean more than a 100 percent increase in wages for those at the bottom of the salary scale and similarly large increases for those earning more.

Although this amount would still not completely close the debilitating wage gap between full-time and part-time instructors, it would nonetheless be an extraordinary step in the direction of full parity and would dramatically alter the way the university is organized. No longer able to depend upon the cheap labor of adjuncts to balance its budget, university administration would be forced to join its students and faculty to agitate for more funding from the city and state to cover future expenses.

Just as important, however, is the fact that if the labor of adjuncts was no longer so cheap, the university would have much less incentive to continue to use them in such great numbers, which would force a move toward a full-time faculty. Although there will always be a need for part-time adjuncts to teach specialized courses or to help cover unexpected enrollment increases, ask anyone who cares about the future of higher education, and they will tell you that the vast majority of the faculty at any college or university should be full-time. Full-time employment affords these workers the stability and time to be better teachers and researchers. Indeed, although it is incredibly difficult to measure teaching quality, and although most measurements of teaching quality are notoriously flawed, inaccurate, and often biased against women and teachers of color, study after study has shown that as the use of adjunct faculty increases, teaching quality declines.

In addition to improving the quality of teaching, the job security that comes with full time employment would allow more faculty to expand and develop their research and to explore controversial ideas in the classroom. Importantly, it would also increase the number of engaged faculty members and active union members, facilitating organization within the university in the interests of students and for the public good, while opening up space for criticism of administrative malfeasance and suggestions for more radical transformations of the university and its mission.

Build a Rank and File Movement to Win

Although the demand for “7K” has the potential to inspire and mobilize union members as well as the broader university community, one of the unintended consequences of such a bold call for equity is that there is a natural inclination among even the most stalwart union activists to treat this demand as a starting point for negotiations rather than the minimum acceptable for a contract agreement. In other words, there is the chance that this demand will not be taken up as a bold call to remake the university, but merely as a tool that can be used to win some modest economic gains for adjuncts without actually addressing the deeper corrosive problem of the two-tier labor system. Such a reformist strategy, if followed, would almost guarantee the continued exploitation of adjunct faculty for decades.

However, this does not have to be the case. CUNY faculty and staff can win 7K for adjuncts, but they will have to commit themselves to this demand from the start and be willing to fight for it to the end. The PSC’s current contract expires November 30 and the union has called for a mass rally in front of the CUNY Board of Trustees meeting at Baruch College on Monday, December 4. The rally is a good indication that the union is serious about mobilizing for this contract, and a big turnout of adjuncts would send a clear signal to the administration, as well as the union leadership, that they are ready to fight for 7K.

Of course, a successful contract campaign will require more than the usual rallies and staged-for-the-cameras acts of civil disobedience. Labor agitation among public sector unions in the U.S. has reached historic lows, and the PSC’s last contract — which, despite a successful strike authorization vote, took a full six years to settle — is a good example of why public sector unions everywhere must break with the trend of “labor peace” if they hope to make any gains under the regime of neoliberal austerity. The history of labor and the history of struggle at CUNY both serve as evidence that substantive change requires radical tactics. Therefore, winning a fair deal for adjuncts will require the whole toolbox of labor agitation, up to and including limiting teaching to contractual requirements, slowdowns, work-stoppages, pickets, rolling strikes, and walk-outs by faculty, staff, and students. Such actions will require a strong and militant rank and file that is willing to challenge the Taylor Law as well as the union leadership who will have to be pushed to move beyond their comfort zone.

To build this rank and file power, adjunct faculty and their allies need not wait for marching orders from the union. Instead, they should take the lead and begin to organize and educate around the demand for 7K immediately, reaching out and explaining to faculty and students why this is such an important demand and developing grassroots campaigns to fight for it both inside and outside of the union.

The call for a $7,000 minimum per course for CUNY adjunct lecturers is a righteous demand, grounded in basic moral principles of labor equity. As such, it should be supported by everyone who cares about building strong, fighting unions. Although winning will not be easy, a successful rank and file campaign of faculty and students willing to confront the Taylor Law would be an inspiration to higher education and public sector workers across the country. It would also open up new spaces for radical transformations of the university that could make CUNY the site of continued struggle.