This article was first published in La Izquierdo Diario examining the book, The Making of Global Capitalism: The Political Economy of American Empire (2012) by Leo Panitch and Sam Gindin.

As we approach the 100th Anniversary of V.I. Lenin’s Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, several modern works are now discussing the usefulness of the coordinates laid down in this and other works by Marxist authors.

Since the start of the warmongering offensive launched by George W. Bush, this concept has returned to the center of Marxist debate, after having fallen into obscurity during the times of ideological retrogression amid the conservative offensive of the 1980s. As Indian Marxist economist Prabhat Patnaik noted, while imperialism in the mid-1970s “perhaps occupied the most prominent place in any Marxist discussion,” only three years later, the topic had “disappeared from the pages of Marxist journals.” Now, “younger Marxists looked bemused when the term is mentioned.”1

Since the beginning of the new millennium, a new series of theoretical elaborations have taken up discussion on features of imperialism in our times of internationalized capitalist production, from the basis of Marxist theory. Some focus on a critical assessment of the “classical” elaborations on imperialism — the works written by Marxists during the first decades of the 20th century, namely Lenin, who marked out a new strategic direction of the epoch.

David Harvey, Ellen Meiksins Wood, Giovanni Arrighi, Robert Brenner, and Perry Anderson have contributed some of the more noteworthy interventions, which we will partly address in this series.

One of the first books to reinitiate the debate was Empire (2000), written by neo-autonomist philosophers Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt, who took up this theme while constructing their theory of an empire without a center: “The United States does not, and indeed no nation-state can today, form the center of an imperialist project,” they wrote three years before the US invasion of Iraq.2 This thesis crashed headlong into reality when the Bush administration launched the US neo-conservative imperialist agenda.

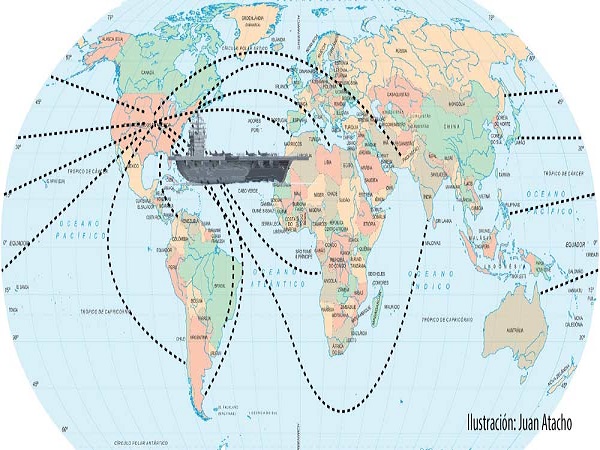

In this article, we discuss The Making of Global Capitalism: The Political Economy of American Empire by Leo Panitch and Sam Gindin (Verso Books, 2012). The book’s central argument is that the US has dominated the planet since World War II, integrating other powers (and countries) by way of subordination to its “informal empire.” The authors see a kind of “super-imperialism” (a term which the authors do not use but is nonetheless very close to their characterization), which they differentiate from the conditions of inter-imperialist rivalry that Lenin had characterized as a central element of the “new epoch.”3

Their proposition

The Making of Global Capitalism meticulously highlights the historical rise of the United States to the rank of world superpower. Using a wealth of documentary evidence, the authors explain the link between US domestic and foreign policy. They argue the state gradually accumulated the capacity to shape global capitalism according to the needs of US corporations, while still giving importance to systemic stability for the sake of all global capital, an impetus for the development of multilateral institutions serving this purpose.

There are two fundamental theses which structure the book. First, to understand the emergence of contemporary global capitalism, it is necessary to consider first and foremost the role played by the states in its construction. Taking issue with various “globo-philic” ideas, the premise is that, far from being the result of economic determinants that operate “automatically,” global capitalism has depended on the capacity of the state to create mechanisms suitable for the internationalization of capital: primarily, the capacity for the US state to function as guarantor of the accumulation of capital on a world scale.

The book is about globalization and the state. It shows that far from being an inevitable outcome of inherently expansionist economic tendencies, the spread of capitalist markets, values and social relationships around the world has depended on the agency of states––and of the US in particular (p. VII).4

The book’s second key thesis is that the United States’ transformation into world superpower, and the subordinating integration of the rest of the old European powers into its orbit (along with other capitalist formations) occurs through the formation of an informal empire: the US has “succeeded in integrating all the other capitalist powers into an effective system of coordination under its aegis” (p. 8).

Departing from the perspectives of Hardt and Negri, the empire of Panitch and Gindin is one with a clear center: the US state, which operates worldwide through a series of multilateral institutions and a distinct hierarchy of “vassal” states. The United States was able to accomplish what they refer to as the “stable basis for the spreading and deepening of global financial markets,” owing to what they define as the internationalization of the state. This definition should not be understood as the emergence of a new “proto-global state” through the new institutions that emerged in the post-war period. Instead, these institutions “were constituted by national states,” although for Panitch and Gindin, these states “were themselves embedded in the new American Empire, and with their internationalization, they now “had to accept some responsibility for promoting the accumulation of capital in a manner that contributed to the US-led management of the international capitalist order” (p. 8).

A world order in the image and likeness of the superpower

Panitch and Gindin demonstrate how the world order after WWII is the result of the projection of the character of development and capitalist governance from the US to the rest of the world. The study begins with an analysis of how US capitalism was forged and the particular features displayed by the state from the beginning.

The New Deal emphasized “the distinctive interdependence between the state and capital, and the deep historic orientation of the US state towards the promotion of capitalism, [which] would prove critical for the specific way it would play its emergent role as the manager of capitalism on a world scale” (p. 63). During the interwar period, the United States finalized the development of the capabilities that it deployed after the war to ensure the creation of an integrated, transnational order, one which was supported by the commitment of all states to give guarantees and equality before the law to all capitals. The Treasury Department and the State Department were the key agencies in this development. In the post-war period, these dependencies would play a central role in forging the coordinated actions of the states.

The Bretton Woods agreement on the international monetary order, the intervention of the US during the postwar reconstruction of Europe, along with big government efforts and the destruction of war laid the foundation for an exceptional period of growth that lasted through the end of the 1960s. International trade increased 40 percent faster than gross production during the 1960s. The rate of increase of foreign direct investment was even higher, at two times that of production.

The Making of Global Capitalism describes the crisis that brought an end to this boom as the “contradictions of success” (p. 111). But it also points out how the crisis gave way to a renewal of imperialist impulse, which from the 1980s onwards led the US to promote higher levels of global integration. The way in which this crisis was resolved “was decisive for realizing the project for a global capitalism under US leadership in the final two decades of the twentieth century” (p. 164). A series of important transformations took place, among them the relationship between finance and industry, leading to “a much larger share of total corporate profits” going to the financial sector (p. 187). In addition, “major restructuring” within many of the country’s core industries also took place (p. 188). Perhaps most importantly, there was a shift towards high-tech manufacturing, a “new industrial revolution [that] was largely American-led” that swept across computer and telecommunications equipment, pharmaceuticals, aerospace, and scientific instruments (p. 190). This reconstituted the foundations of US capitalism, and laid the groundwork for the internationalization of production that was commanded by the United States.

The Empire is not imperialism

The great virtue of The Making of Global Capitalism is that it maintains that the international system of formally independent states can be (and effectively is) the foundation for constituting relations of servitude and control. This argument is critical, as some have questioned the current relevance of the theory of imperialism given the proliferation of sovereign states over the last 60 years, which some interpret as an overcoming of the dependent and (semi) colonial status of the former colonies.

The problem is that Panitch and Gindin do not draw greater distinctions between the relationships established by the US with the old imperial powers, and those with other states. They do show more resources were dedicated to the European recovery and to the integration of these countries into a US led international order. Beyond this, they do not distinguish the mechanism of imperial control between the US and non-European states, suggesting equal integration.

For Panitch and Gindin, the relationships between these powers is a different nature from those characterized by Lenin in Imperialism. In his famous polemic against Kautsky, Lenin took issue with Kautsky’s view that inter-imperialist confrontation was not inherent to the nature of the imperialist phase, and that powers acting in a concerted fashion could push for their mutual interdependence within an internationalized economy. Lenin instead argued that one of the “historically concrete features” of contemporary imperialism was precisely the rivalry “of several imperialist powers.” While Kautsky suggested that this was a situation that could be overcome peacefully, Lenin insisted that it was the uneven development inherent in the very dynamics of global capitalism that would make any lasting equilibrium between the powers on the basis of a stable accommodation of their relations impossible.

The Making of Global Capitalism bases itself on the incontrovertible truth that, since the end of World War II, US power has been far superior to that of the other powers and accounts for how the US state created the conditions during the post-war reconstruction period for the involvement of all states in sustaining an integrated capitalist world space, while dismissing the rivalry between the imperialist powers as something belonging to the past. For Panitch and Gindin, this is not only due to a historical change, but also reveals a defect contained within the theories of imperialism developed by Lenin and others at the beginning of the 20th century, which contain “their elevation of a conjunctural moment of inter-imperial rivalry to an immutable law of capitalist globalization..”5 Linked to this is what the authors see as the “especially defective” aspect of these theories, “their reductionist and instrumental treatment of the state,” in that they consider the predominance of the economic determinants as a starting point for understanding inter-state relations.6

But something missing from Panitch and Gindin’s book is a proper theorization of the state and of the social relations on which it is based. Descriptions of the actions of the US state and the “internationalization” of the states abound, but they are not satisfactorily conceptualized nor registered in a theory of inter-state relations. In the case of the US, the imperial power, its agencies rise above the immediate perspective of the capitalist class to direct the construction of global capitalism. On the other hand, all the other states are limited to simply responding collaboratively to the imperial power’s dictates in the interest of global accumulation.

The proposal of situating the determinations, possibilities and limits of the actions of all states, and the reciprocal constraints in the system of states, and taking this as the starting point of the accumulation of capital on a global scale, as the “classical” theory of imperialism does, in no way falls into “instrumentalism.” Globalized capitalism under the impulse of the United States cannot overcome the contradictory relationship between what David Harvey defines as “molecular processes of accumulation,” and the territorial logic of power in which nation states continue to play a key role. Far from being passive actors to the requirements of the “empire,” they actively intervene in an effort to defend certain sectors of the bourgeoisie within its national borders and to increase their own state power (to ensure control over the subaltern classes and preserve their comparative strength to other states). Because the world economy in the imperialist stage is united in “a system of mutual dependence and antagonism,”7 it becomes necessary to consider the mutual determination of the relationship between the economy and the social classes within each state as well as the relations between states, relations that for Trotsky were all part of what he defined as capitalist equilibrium.8 The fact that “capitalism has been unable to develop a single one of its trends to the ultimate end” can be clearly seen in the efforts made to try and manage the contradiction between the increasingly internationalized productive forces and the persistence of their national base.9

Without discussing these issues, the narrative of Panitch and Gindin, in which the US state does not face greater restrictions on its ability to supervise and transform the global system and inter-state relations, is an exaggeration of the coherence that the shaping of the global economy has adopted. Although the authors do register that the US project has run into contradictions, they emphasize the ability of the US to orchestrate ways out that allow for continuation based on previous plans.

It is worth remembering that Perry Anderson, who also tends to emphasize the strength of American power, has nevertheless highlighted the increasing difficulties that it has had in perpetuating the conditions of its own preeminence. In his opinion, the “Empire” is becoming “disarticulated from the order it sought to extend. American primacy is no longer the automatic capstone of the civilization of capital.”10 The author thus confirms the increasing limits that American hegemony faces, even if today there is no one who can dispute this hegemony.

The overestimation of the capabilities of the imperial power is eloquently expressed in the ability that Panitch and Gindin grant to it for containing crisis. They assert that the response to the outbreak of the Lehman crisis, and in the most critical moments that have occurred since then with the debt crisis in Europe, have been one that has seen coordinated action prevail. This may have served to take emergency action against the threat of a new Great Depression, but such action has lacked any effectiveness in dealing with the underlying problems. When we refer to the problem of how to restructure the economy so as to give an impulse to capital accumulation, we see a “zero sum game” that, far from being able to come about through a global consensus, has exacerbated competition and seen unilateral departures. Since 2008, the “containment” of the crisis cannot disguise an ominous landscape, where the perspective for a long period is one of poor growth rates accompanied by high financial instability. The crisis that is making its way around the globe is producing a political polarization which strengthens the responses of those who tend to question the global liberal order from both the right and the left, something that is happening with great force in Europe. Under these conditions, preserving the unity of the major states under their plans becomes an increasingly difficult objective for the United States.

That US imperialism could act as an “empire” for such a prolonged period after the Second World War has less to do with a change in the nature of the relations between the various powers, and more to do with a whole set of conditions that have allowed the United States to prevent, until now, the “uneven development” that would turn the balance of forces against it. The indications that this is now beginning to irredeemably change are occurring on several levels.

We will continue to discuss the work of other authors who have developed various critical aspects of the debate around contemporary imperialism in future articles.

1. Prabhat Patnaik, “Whatever has happened to imperialism?”, Social Scientist, Vol. 18, Nos. 6-7, New Delhi, 1990.

2. Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Empire, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2000, p. xiv.

3. “In this case a single imperialist superpower possesses such hegemony that the other imperialist powers lose any real independence in the face of it and are reduced to the status of small semi-colonial powers,” Juan Chingo and Gustavo Dunga, “¿Imperio o imperialismo?” (Empire or imperialism?), Estrategia Internacional (International Strategy) No. 17, Autumn 2001.

4. The Making of Global Capitalism: The Political Economy of American Empire, New York, Verso, 2012. Page numbers for all quotes are indicated in the body of the text in parentheses.

5. Leo Panitch and Sam Gindin, “Global Capitalism and American Empire,” Socialist Register, London, The Merlin Press, 2004.

6. Ibid.

7. Leon Trotsky, The Third International After Lenin (1928), Chapter 1, “The Program of International Revolution or a Program of Socialism in One Country?”.

8. Paula Bach, prologue to Leon Trotsky, Naturaleza y dinámica del capitalismo y de la economía de transición (The Nature and Dynamics of Capitalism and the Economics of Transition), Buenos Aires, CEIP, 1999.

9. Leon Trotsky, “Marxism in Our Time” (April 1939)

10. Perry Anderson, “Imperium”, New Left Review 83, September-October 2013, p. 111.