Nineteen sixty-eight was a revolutionary year.

The resistance against the Vietnam War and the revolutions in Cuba and Algeria inspired youth around the world to fight the repressive state and, in some cases, capitalism itself. In some capitalist countries, youth and some sectors of workers fought for revolution. Nowhere is this more evident than in the French May of 1968, which was marked by student and worker strikes. In Stalinist countries, the youth wanted not only socialism, but also to bring down the corrupt and authoritarian bureaucracy. This was evident in Prague, where the rebellion against the bureaucracy was violently repressed by the USSR’s tanks.

Mexico was no exception, even though Mexican youth organized primarily against the authoritarianism of the Institutional Party of the Revolution (PRI)—which had held an almost exclusive monopoly on the government since the Mexican Revolution. The PRI had maintained its power by repressing youth, workers and peasants, as well as by effectively banning other political parties and committing massive voter fraud. The PRI maintained a one-party monopoly on Mexico under the guise of “free elections” which had brought into power President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz.

The youth in particular were intensely repressed and criminalized. The police repressed and broke up everything: rock concerts, festivals, soccer games and even art exhibits. These extreme measures hindered cultural expression and free movement, making the police particularly hated in Mexico City. At the same time, the youth were touched by the growing global left movements. Socialist groups began to emerge, discussing the Cuban Revolution, the Vietnam War and U.S. imperialism. Public universities particularly the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) and the National Polytechnic Institute (IPN), served as a hub of politicization for working- and middle-class youth. Both the UNAM and IPN also have a system of “early college” for high school students, which in this period radicalized even younger Mexicans. For example, UNAM’s department of political science went on strike and occupied their department to free Demetrio Vallejo—a political prisoner who had helped organize a massive railway workers’ strike in 1959. He had been locked up since.

The Spark

The spark that lit the massive student movement was the repression of high school students studying at IPN. On July 26, five departments at the IPN organize a strike and occupation, representing thousands of students. July 26 also marked the start of the Cuban Revolution, and the students from IPN and UNAM had organized contingents to go to a commemorative march in downtown Mexico City. At the Zócalo, the center of Mexico City, this march was violently repressed. Many students were wounded, and the police entered the offices of the Communist Party, arresting many members. To avoid the repression, students hid away in a nearby high school, San Il de Fonso, and took it over as a defensive position against the police and right-wing shock troops (porros). Within a few hours, the students had successfully defended their occupation, first from the police and then from these right-wing groups. Teachers, students and parents united to fend off these attacks using rocks, desks and other school materials. Popular opinion was on the side of the students, with people all over the country expressing indignation at the government attacks. In repudiation of these attacks, all IPN students went on strike—some 300,000 students. The university was entirely taken over by students.

On July 30, the military took San Il de Fonso from the students using tanks, jeeps and bazookas. Forty students were severely wounded, and 1,000 were arrested. As a result, universities in the states of Chiapas, Tabasco, Puebla, Jalisco also went on strike. The next day, the UNAM students also went on strike, representing another 300,000 students. Here too, the students organized an occupation.

On August 1, because of the brutality of the police offensive, as well as the popular support from teachers and families, the president of UNAM called a protest, which 100,000 people attended.

At the same time, the government continued an intense counteroffensive. The media tried to paint the youth as Communist criminals, and the police continued to arrest leaders. But the damage was already done; the population was on the side of the students, and the student movement was growing stronger.

As students begin to mobilize, there emerged student assemblies to democratically decide what to do. On August 2, the National Council of Striking Students was created, with elected representatives from each department, including students from other states. These representatives were revocable and rotated to include more people in leadership positions. Hundreds of students attended the council meeting and came up with a list of demands, including freedom for political prisoners, removal of the military generals in command of Mexico City’s police, abolition of the police who specialized in repressing protests (known as Granaderos) and the repeal of a law prohibiting conspiring against the government. They also organized the day-to-day functioning of the occupations: security detail against the police, cleaning, cooking and political education classes. They organized brigades of students to go into the community to explain the students’ struggle to the Mexican population. They had to go in groups, for fear of police detention and arrests. They organized “lightning rallies,” where small groups of students read out the demands and quickly retreated from the cops. The National Council of Striking Students also organized a student press and distributed pamphlets to spread the news of the strike.

The National Council of Striking Students was the most advanced element of the student insurgency of 1968. Students used methods characteristic of the working class: councils of elected delegates for democratic decision making. These same kinds of councils have emerged throughout history in moments of intense working-class struggle: soviets in the USSR, the “coodinadoras interfabriles” (inter-factory coordinating committees) in Argentina and the more recent 2006 Popular Assembly in Oaxaca. The students forged a new tradition in Mexico: organs of democratic decision making to strike against the state as one.

The Massacre

For the next two months, the National Council of Striking Students won the respect and support of the working class and poor as it became known as the primary opposition in the streets against the PRI. The PRI feared that the student mobilization could spur a general movement against the government. In the large labor union controlled by the union bureaucracy of the PRI, there arose an anti-bureaucratic movement. For example, sectors of the working class began to send contingents to student marches, in direct conflict with the leadership of the labor unions.

The students began to extend their questioning of the PRI, to also question the capitalist system.

Given the risk of radicalization as more sectors organized to fight, the Mexican government decided to quickly put an end to the movement. This was particularly important because the last thing the Mexican government wanted was an international embarrassment during the Olympics, slated to begin in Mexico City a week and a half later.

On the evening of October 2, the Striking Students Council organized a massive mobilization at the Tlatelolco Plaza. Not only students but also railway workers, phone workers, doctors, nurses, teachers and families attended the protest. Thousands of military police surrounded the protest, which was a common occurrence. At the end of the rally, a helicopter flew over the area and began to shoot flares above the crowd—the sign for the police to attack the protesters. Snipers opened fire on students with machine guns. Police disguised as civilians also shot into the crowd. They wore white gloves to identify themselves to one another. The military drove into the crowd with tanks.

Over 300 people were killed, according to human rights organizations. At least 700 were wounded and 5,000 arrested. The military did not allow families to come identify the bodies, and no government official or military officer has been punished for this massacre.

The unprecedented repression liquidated the Striking Students Council and the occupations.

The flame of those brave students who mobilized in 1968 has been carried on by today’s Mexican student movement. In 1999, another massive student strike was organized at the UNAM, creating alliances with the working class and shutting down the university for months.

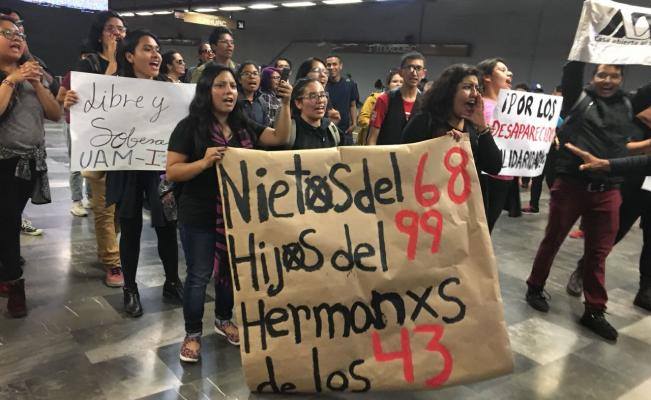

Then the student movement went into action again, organizing protests of hundreds of thousands against the disappearance of 43 students in Ayotinzapa—students also disappeared by the PRI. Much of the UNAM went on strike just last month against right-wing attacks by the government- and university-funded shock troops. They organized massive mobilizations and a university-wide strike committee.

Today’s students say: We are the grandchildren of ’68, the children of ’99 and the siblings of the 43.