Image from El Nuevo Diario

“History never repeats itself, but it often rhymes.” This aphorism, attributed to the great U.S. humorist and anti-imperialist Mark Twain, implies that to understand the rhymes of history, one must understand the original stanzas.

This series of articles argues that a winning strategy to definitively defeat imperialism in Central America is to be found in the history of the region’s anti-imperialist and revolutionary-democratic movements. Both their successes and defeats provide important lessons for today.

The first article in this series examined the failures of the revolutionary liberal bourgeoisie, represented by Francisco Morazán Quesada, to fulfill their program of creating a Federal Republic of Centroamerica, composed of the five former provinces of the Spanish colonial General Captaincy of Guatemala: Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua and Costa Rica. In coming articles, we will look at some revolutionary processes in the 20th century.

William Walker and Manifest Destiny

The Old Trujillo Cemetery lies between the two mountains to the west, which look down upon the small city of Trujillo, perched on a cliff along the northern Honduran coast, and the three Garifuna fishing villages that line the shore to the east. In a small plot, surrounded by a rusted steel fence, a small slab of weathered stone chiseled with a barely discernible name bears a simple plaque that reads:

William Walker (2)

Fusilado (Shot)

12 Sept. 1860

The bones decaying in this tomb, as the years, decades and centuries drift by, are those of an agent of history best described by Marx in these terms:

Only by acquisition and the prospect of acquisition of new Territories, as well as by filibustering expeditions, is it possible to square the interests of these poor whites with those of the slaveholders, to give their restless thirst for action a harmless direction and to tame them with the prospect of one day becoming slaveholders themselves. (1)

Walker, a Nashville lawyer, doctor and journalist, was not poor, but he was a leader of those poor whites who indeed had a thirst for action. A polymath who had graduated as a lawyer and a doctor by the age of 20, Walker’s own “thirst for adventure” was not harmless for his adversaries, nor did it tame his unbridled ambition, an ambition forged in the ideology of the doctrine of Manifest Destiny and tempered by the raw politics of the United States.

In the spring of 1851, Walker and his followers set out to expand the territory of the slave states by conquering Baja California Sur, which was then, as it is now, part of Mexico. After seizing a few lightly defended towns and declaring the Republic of Sonora, Walker was chased out by the Mexican military. Walker then returned to New Orleans, where he had previously owned a newspaper.

Just as it is today, North American imperialism was the continuation of domestic policy by foreign means. The overarching U.S. political framework of the time was the constant encroachment and expansion of slavery into territories that were originally free states. From the Missouri Compromise to the Dred Scott decision, the slaveholding bourgeoisie of the southern United States steadily guided the domestic policy of successive governments to tip the relationship of forces in its favor. The actions of Walker and his freebooting allies, called filibusters, should be understood in this light.

As Marx pointed out in his pamphlet “The North American Civil War,”

“In the foreign, as in the domestic, policy of the United States, the interest of the slaveholders served as the guiding star. … Under [President Buchanan’s] government northern Mexico was already divided among American land speculators, who impatiently awaited the signal to fall on Chihuahua, Coahuila and Sonora. The unceasing piratical expeditions of the filibusters against the states of Central America were directed no less from the White House at Washington. In the closest connection with this foreign policy, whose manifest purpose was conquest of new territory for the spread of slavery and of the slaveholders’ rule, stood the reopening of the slave trade, secretly supported by the Union government. Stephen A. Douglas himself declared in the American Senate on August 20, 1859: “During the last year more Negroes have been imported from Africa than ever before in any single year, even at the time when the slave trade was still legal. The number of slaves imported in the last year totaled fifteen thousand.”

In 1855, Walker had another opportunity to pursue his quest to fulfill this Manifest Destiny (3) of expanding the slave territories. This time it was in Central America. Through his contacts in New Orleans, the commercial bourgeoisie of the Nicaraguan city of León asked Walker to help defeat their adversaries. Grouped in the Liberal Party, Walker’s contacts in León were fighting a continuous civil war with the agrarian interests and clerical reaction headquartered in the old Spanish colonial city of Granada.

Backed by slaveholders and planters, Walker arrived with several hundred followers looking for adventure and fortune. They captured Granada, and within a year, Walker had managed to conduct a military campaign throughout the country that strengthened his position. He eventually ran a bogus election and became president of Nicaragua.

One of his first acts was to rescind the law outlawing slavery and to make English an official language. In this he had the support of U.S. President Franklin Pierce, a Democrat who saw the anti-slavery abolitionists, not the proslavery secessionists, as the greatest threat to national unity.

Walker increased the military budget, the number of garrisons and began fortifying military positions along the Rio San Juan, the border with Costa Rica. The river was the centerpiece of a project to build a canal, to be dug from Lake Nicaragua, that would link ports on the Atlantic and Pacific coasts. (This is the same as the present-day project which has pitted small landholding farmers and the international environmental movement against the Ortega-Murillo regime.)

This project was owned by the railway tycoon Cornelius Vanderbilt, (4) who had secured the concession to build it. Walker made a fatal mistake by seizing two steamboats owned by Vanderbilt, abrogating his concession rights and turning the project over to Vanderbilt’s two local agents who had helped him seize the steamboats.

The United Army of Central America

This increase in Nicaraguan military activities alarmed the country’s Central American neighbors, none more so than the president of Costa Rica, Juan Rafael Mora Porras (5), an exemplary representative of the dominant commercial bourgeoisie centered in San José, and his brother José Joaquín, a career officer in the small but skillful Costa Rican army. As Walker’s forces encroached on what the Costa Ricans saw as their territory, Porras Mora declared war on Walker’s Nicaragua. He summoned the Costa Rican people to arms, and thousands of mostly workers and small landholders answered his call.

Mora Porras assembled a force of 3,000 soldiers and reservists from Costa Rica, aided by a contingent of Salvadorans who had fought with the armies of Francisco Morazán Quesada. He marched from San José to Liberia, where he was joined by a column headed by General José Cañas.

Walker made his move in March 1856, marching 300 troops out of the garrison at Rivas to begin the occupation of northern Costa Rica. He stopped his advance at the hacienda of Santa Rosa to rest. This ranch in the northwest extremity of Costa Rica has a hill that commands a view east to the fumaroles of the Tilaran Mountains, and north across the plains of Guanacaste. This hill has played a strategic role in three major battles in the history of Central America and Costa Rica, but none as important as the battle that took place in the early morning of March 20, 1856.

In a surprise attack at 4 a.m., which caught Walker’s invading force totally off guard, 700 Costa Ricans stormed the Carsona, the Big House, where the filibusters were resting, and in less than 20 minutes they overran the post, killing 19 and capturing 27. A mistake by an outpost guard, however, allowed the remaining filibusters to escape and return to their garrison at Rivas.

Nonetheless, it was the first defeat of the filibusters on Central American soil, and the first in a string of military defeats to come. It represented a defeat for the policies of the Pierce government, which had recognized the Walker regime as the legitimate government of Nicaragua. It was also a defeat for the U.S. slavocracy.

Just as importantly, it convinced the other nations targeted by Walker—Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador—that a united effort was necessary to defeat the invaders. In a prescient speech delivered in April 1856, Jose Joaquin Mora Porras outlined the nature of the war:

This struggle is not only a national one … [though] limited today to the territory of Nicaragua, it has a relationship to the whole of the Hispano-American continent, for the demented pride of the Filibusters is to conquer Cuba, Mexico and Panama, after taking possession of Central America. [Author’s translation] (6)

Heeding Mora Porras’ warning, Honduras and El Salvador dispatched troops who, together with reinforcements from Costa Rica under the command of Cañas, attacked the filibusters in Rivas, inflicting many casualties. After this battle, made famous in the legend of the drummer boy Juan Santamaría, the combined armies of the three countries, later joined by troops from Guatemala, prosecuted the war as the United Army of Central America (UACA).

Walker, seeing his position deteriorating, appealed to the southern slaveholders for help. They responded with supplies and more poor white adventurers from the parishes around Louisiana. Meanwhile, however, the Pierce government had come under pressure from both the government of Costa Rica and Cornelius Vanderbilt (whose steamboats Walker had expropriated). Pierce rescinded his recognition of Walker’s government.

The UACA pressed its advantage through the campaign of 1856-57 and ultimately forced Walker to surrender on May 1, 1857. Thanks to the efforts of both the Costa Rican government and Commodore Vanderbilt, he was allowed to surrender to the United States Navy. He was extradited back to New York, where he was treated as a hero in anti-abolitionist and pro-imperialist circles.

Before surrendering, Walker revealed the true face of imperialist savagery. In December 1856 the city of Granada, the oldest and one of the most beautiful Spanish colonial cities in Central America, was surrounded by 4,000 UACA troops. Realizing the hopelessness of his position, Walker’s general ordered his troops to raze the city as an example of, as he put it, “the tough nature of American justice.” When the UACA entered the city after the filibusters had withdrawn, all that was left was a stone painted with the words “Aqui Fue Granada”—Here Was Granada.

Similarly, after the filibusters definitively lost control of Rivas, they filled all the wells with corpses, which precipitated a cholera epidemic that ultimately killed 10,000 people, nearly 10% of Costa Rica’s population.

Lessons for Today

What lessons can we learn today from this little-known and obscure war? After all, haven’t the form and content of imperialism changed in the past 160-odd years?

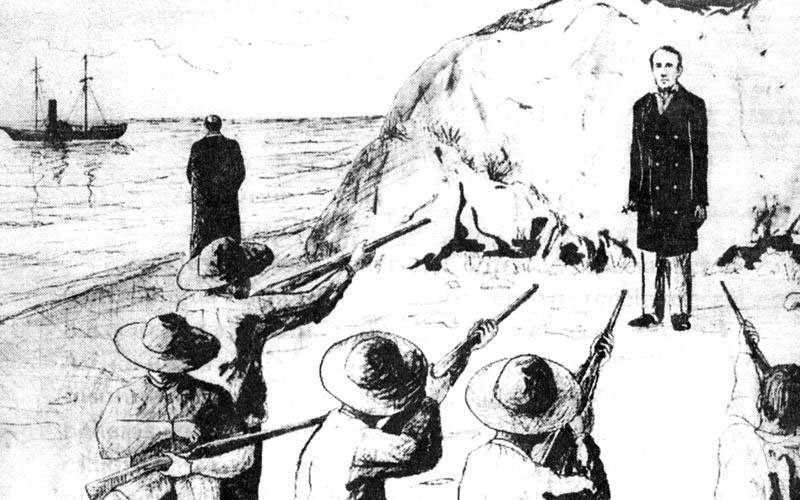

The basic lessons of Walker’s defeat are as relevant today as they were the day Walker met his end against a wall in Trujillo.Both Mora Porras and Walker were executed by firing squads, after attempting comebacks. Walker was captured in Honduras by the British in 1860 and handed over to the Honduran government. Mora Porras was deposed in a coup in 1859 by his arch enemy, and representative of the agrarian bourgeoisie centered in the former capital city of Cartago, José María Montealegre Fernández. Assembling a small force at the city of Puntarenas, he took the city but was defeated a few days later at the Battle of La Angostura. He was summarily tried and shot. His brother-in-law, General José Cañas, was executed the next day. His brother, José Joaquin, escaped.

The working people of Centroamerica are anti-imperialist to their bones, thanks to the long history of U.S. meddling in the region. Today, they face oligarchic governments propped up by imperialism, like the Juan Orlando Hernández regime in Honduras and Jimmy Morales’ death squad regime in Guatemala. In El Salvador they face daily violence, and in Nicaragua, crushing poverty.

When Mora Porras called the people of Costa Rica to arms, over 10% of the country’s population responded (in Mexico today, such a response would build an army of 13 million).

History suggests that a thoroughgoing anti-imperialist politics can mobilize the regional masses in struggle for a program of national and social liberation. Subsequent events, which will be analyzed in the next article of this series, have borne this out—not the least of which were the massive demonstrations against the Free Trade Agreement of the Americas in Costa Rica.

The key to the victory over the filibusters was a united armed response by the political forces in the region, nominally both Liberal (Mora Porras) and Conservative (Rafael Carrera from Guatemala).

This lesson is one that the imperialists learned well. As we stated in Part 1 of this series, the ability of North American imperialism to keep the revolutionary struggles divided on a national basis has been their main strategic focus since the regional war waged by Francisco Morazan, and the fight against Walker was to be the last time a united Centroamerican military force went to war against imperialism. We shall return to this thesis in the following articles of this series.

The defeat of the imperialists in Central America requires the same united response. It will not come from the bourgeoisie of this region, for they have long ago sold themselves to an imperialism in which they are deeply entwined. Rather, it will come from the leadership of the working class and its allies in the rural workforce and the urban barrios with insurgent women and youth, as we saw in Guatemala in 2015 and in Honduras in 2017.

Just as the bourgeoisie constructed their international organization, the United Army of Central America, to assemble the forces necessary to conduct their anti-imperialist struggle, so too must the workers, the poor and the oppressed of Our America construct their international organization. With such an organization, they will be able to coordinate and combine their respective national struggles into one regional insurrection, one that will leave the horror of imperialism and its national allies moldering, like the bones of William Walker, in a Central American grave.

Notes

1. Karl Marx, “The North American Civil War,” Collected Works, vol. 19, translated by Progress Publishers, Moscow, transcribed to the Marxist Internet Archive by Bob Schwarz, found here: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/Marx_Engels_Writings_on_the_North_American_Civil_War.pdf

2. A long list of primary and secondary sources about Walker is available here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Walker_(filibuster).

3. The doctrine of Manifest Destiny, with its quasi-religious overtones, was first enunciated in the United States Democratic Review in 1839. It was, and is, the central ideological construct of U.S. imperialism, encompassing the notion of “American exceptionalism.” The term was coined in the same journal in 1845 by John O’Sullivan, who explained that because the system of U.S. government was unlike any other that had come before, the role of the United States was to link its destiny with the future.

It is a thoroughly racist idea, implying that the white, European settler populations had a unique, God-given role to occupy the whole North American continent and build “the shining city on the hill,” a phrase derived from the biblical prophecies of St. John the Divine in the Book of Revelation. Its similarities with Zionism allow the evangelical Christian right to see themselves as Christian Zionists.

4. For the battle between Vanderbilt and Walker (representatives of an ascendant industrial bourgeoisie and a declining agrarian slavocracy, respectively), see https://news.vanderbilt.edu/archived-news/register/articles/index-id=6686.html.

5. For more on Mora Porras, see https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juan_Rafael_Mora_Porras.

6. Quoted in Juan Rafael Quesada, “La guerra contra los filibusteros y la nacionalidad costarricense,” Revista Estudios, no. 20, 2007, Universidad de Costa Rica.