Debacle. Catastrophe. Collapse. Joe Biden’s “Saigon Moment.” When it comes to the scale of what has taken place, the terms used to define the humiliating withdrawal of the United States from Afghanistan speak for themselves. It is not only a defeat of the United States, but for NATO as a whole, which went along on the military adventure with human and financial resources. The strategic effect of what is now the second military defeat of the United States at the hands of an infinitely weaker enemy will surely be seen in the coming period.

The “War on Terror”

The chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan is the first major crisis of the presidency of Joe Biden, who had been enjoying a relatively long honeymoon thanks to having capitalized on “anti-Trumpism” and above all on his “populist” measures to sustain economic recovery and consumption.

In a press conference just a little over a month ago, Biden had offered his assurance that images such as those from the American retreat from Saigon would never be replicated. A sudden triumph of the Taliban was, he said, literally impossible. The president cited intelligence sources that claimed the United States had a year-and-a-half window between the withdrawal of its remaining 2,500 troops in Afghanistan and the fall of Kabul.

The miscalculation could not have been more off.

The Taliban took control of the country with a mere 10-day “blitz,” more because of the defection of the Afghan army and government than because of their combat capability. President Biden has been in damage-control mode ever since. Absent the option of military coercion, he is employing economic sanctions to get the Taliban to negotiate, such as having the Federal Reserve block access to Afghan government accounts and withholding IMF funds. There are still thousands of Americans and personnel from other NATO countries to evacuate, not to mention the mass of Afghans who collaborated with the military occupation and who are desperate to flee the Taliban despite knowing that very few of them will succeed.

To be sure, Biden is not the sole father of this defeat, but he is the one who will have to shoulder the burden. The “war on terror” was a creation of George W. Bush and the neoconservative wing of his administration, which proposed to stem American hegemonic decline with a unilateral, militaristic approach it justified with the terrorist attack against the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001.

The neocon “regime change” experiment was launched first in the war in Afghanistan, and then with the invasion and occupation of Iraq and the overthrow of Saddam Hussein. That was a “war of choice” based on lies about weapons of mass destruction. It soon proved to be a strategic trap that put the United States in the dilemma of either escalating its military presence to sustain the puppet regimes of the occupation or withdrawing and thus leaving a path open for the reorganization of forces hostile to U.S. interests.

In a historical sense, the writing was already on the wall. In the manual of military strategy, wars and neocolonial occupations such as in Afghanistan and Iraq are in the “unwinnable” category.

Barack Obama took office promising to put an end to these wars but ended up increasing the U.S. military presence in Afghanistan, which he considered the “good war.” His administration had as many as 100,000 U.S. troops in the country. He staged the hunt for Osama bin Laden, who was shot dead by elite forces in a modest compound on the outskirts of Abbottabad, Pakistan in 2011. And he became infamous for the widespread use of drones and for expanding military operations to other Middle Eastern countries such as Libya under the guise of “humanitarian intervention.” During his presidency, he was forced to fight the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, a direct result of the U.S. intervention in Iraq. He was also the initiator of the “pivot” to the Asia-Pacific region as a way to contain China.

Under the slogan “America First,” Donald Trump initiated negotiations with the Taliban in Doha, Qatar. The Afghan government wasn’t even invited. Contrary to the neocon “internationalist” policy, Trump returned to the doctrine of intervention only in cases where U.S. imperialist interests were decidedly at stake. That approach actually ended up accelerating the U.S withdrawal from Afghanistan. It also favored alliances with Israel and Saudi Arabia as part of a focus on preparing for coming conflicts between the major powers, China and Russia in particular, which became the priority of national security strategy. With the same objective in mind, President Biden set the 20th anniversary of 9/11 as the deadline for an end to the U.S. presence in Afghanistan.

The balance sheet in figures is catastrophic. In total, sustaining the war and the 20 years of military occupation of Afghanistan cost the United States some $2 trillion. According to the Pentagon, some 775,000 U.S. soldiers fought during this period: 2,448 died and another 20,600 were wounded. To these casualties can be added some 4,000 private contractors and 1,144 soldiers from other NATO countries. Afghans themselves bore the brunt: some 60,000 dead among the country’s armed and security forces, and another 47,245 civilians, according to conservative estimates. They were the “collateral damage” of the imperialist bombardments.

Geopolitical Realignments

The withdrawal from Afghanistan has reignited the crisis within NATO, which was evident at an emergency meeting of the Atlantic alliance called to take initial stock of the failure of the mission. European allies had hoped that Biden’s ascendance to the White House would put an end to the hostility of four years of Trump’s presidency, but instead they were met with a fait accompli — despite having committed their own troops and resources to the occupation of Afghanistan. France and Britain have had to send their own teams to rescue their citizens trapped in Kabul. It would not be surprising if the Afghan outcome were to exacerbate the growing divergence between the European powers and the United States.

At the regional level, the outcome of the war in Afghanistan is reshaping the geopolitical puzzle, with China, Russia, Iran, and Pakistan actively seeking to advance their interests by taking advantage of the vacuum left by the United States. Iran and Russia, historically hostile to the Taliban — both have allies on the side of the Northern Alliance with which they’ve fought — celebrated the U.S. defeat and expressed openness to a dialogue.

Pakistan is experiencing the Taliban’s triumph as a victory of its own. Depending on how events in Afghanistan unfold, however, it could turn into a Pyrrhic victory if it ends up strengthening the extreme Islamist groups that have perpetrated brutal terrorist attacks on Pakistani soil.

Over the past decades, Pakistan has maintained an unstable balance between its relationship with the United States and the semi-clandestine support of its intelligence services (ISI) and military apparatus for the Taliban, which emerged from Pakistani madrassas (Islamic schools) as a radical Islamist faction of the Mujahideen fighting against the Soviet Union. Pakistan served as a refuge for bin Laden when he had to flee Afghanistan, and it also hosted the Taliban leadership that settled in Quetta, in the province of Balochistan. Good relations with China gave Pakistan more room to maneuver. Pakistan’s hope is to have a friendly regime in Afghanistan that would give it “strategic depth” in the event of an escalation of the conflict with India. The latter views the U.S. withdrawal with concern.

After Pakistan, the most important thing for the Taliban is the relationship with China. As was to be expected, China welcomed the U.S. defeat through the pages of the Global Times, not so much because of the significance of Afghanistan, but because China saw it as a preview of U.S. unwillingness to get involved in an eventual conflict in Taiwan. On July 28, in anticipation of what already appeared to be a done deal, China received a Taliban delegation led by the movement’s top leader, Abdul Ghani Baradar. China shares a narrow border pass with Afghanistan that could be its gateway to the republics of Central Asia through membership in the Belt and Road Initiative. Also, Afghanistan could provide some natural resources, particularly the so-called rare earths that are essential for the telecommunications and technology industry. In exchange for economic benefits and investments, China has demanded that the Taliban not intervene in the internal conflict that the Chinese Communist Party regime maintains against the Uyghurs, the Muslim majority in Xinjiang province. It is a risky and uncertain gamble because it depends to a large part on the stabilization of Afghanistan, which at present seems a distant prospect.

The Contradictions of the Taliban

It took the Taliban barely 10 days to dismantle the puppet regime the U.S. had installed in Kabul. The Afghan army, a force of some 300,000 men in which the United States had invested no less than $88 billion, offered no resistance. According to “The Afghanistan Papers,” an investigation carried out by journalist Craig Whitlock, the Afghan army had around 45,000 “ghost” soldiers who existed only as names on the payroll; commanders and other officers collected their salaries and divided up the loot. The Taliban advanced city by city, negotiating the surrender of tribal leaders and local chiefs, and in no time at all the occupation regime simply imploded — for a multitude of reasons. As Carter Malkasian, historian and advisor to the military command in Afghanistan, explains in his book The American War in Afghanistan: A History, foreign occupation runs counter to Afghan national identity. Although his history is written from an imperialist point of view, he admits that ultimately the United States caused prolonged harm to Afghans not out of “humanitarian” concerns but only to defend against another terrorist attack.

The situation in Afghanistan is more than fluid. After the initial shock, some of the Taliban’s internal rivals seem to be regrouping. There have been some mobilizations against them in Kabul and other cities, including Jalalabad. And although it is difficult to verify their authenticity, there have been unconnected incidents involving anti-Taliban forces, including the reorganization of the National Resistance Front, one of the Taliban’s historic rivals, in the Panjshir Valley. Meanwhile, others have opted for a policy of negotiation, including former president Hamid Karzai and other officials of the military occupation governments, who have held meetings with the Taliban in the hope of forming a transitional government.

The fact that the Taliban have still not proclaimed the “second emirate” (the first ruled between 1996 and 2001) a week after entering the presidential palace is an indicator that they have neither internal unity nor sufficient military control to discipline the multiple armed factions, warlords, and leaders of ethnic minorities with whom they dispute shares of local power as well as control over important businesses such as opium production. It was these same lines of fragmentation that denoted the various sides in the civil war of the early 1990s.

So far, the Taliban have tried to project an image of “moderation” compared to the atrocities of the first emirate from 1996–2001. Above all, the aim is to avoid becoming pariahs even before they consolidate a government and manage to stabilize themselves. But according to the journalist Ahmed Rashid (author of several books on the Taliban movement), there is a division between the old generation of the founders, who went into exile in Pakistan and exercise political leadership, and a new generation of local military commanders, many of whom were imprisoned in Guantanamo and other clandestine prisons and who have a more radicalized perspective.

In this context, one of the conflict scenarios that would afford a progressive path forward for the Afghan people could emerge from the resistance of women. What is certain is that the emancipation of Afghan women will not come at the hand of imperialism but from their independent struggle together with the working class. As Tariq Ali puts it in a recent article, quoting a remark by a well-known Afghan feminist in exile, “Afghan women had three enemies: the Western occupation, the Taliban, and the Northern Alliance. With the departure of the United States, she said, they will have two.”

Vietnam Effect?

Differences prevail in the analogy between the American defeat in Vietnam and the debacle in Afghanistan. Two are fundamental and largely explain the relatively rapid recovery of the United States, which 15 years after the retreat from Saigon and its triumph in the Cold War was able to command a decade of one-sided hegemony. The first is the decline of the Soviet Union; the second is the 1972 accord with China, which ultimately allowed the neoliberal relaunching of U.S. imperialism.

These elements no longer exist today. The convergence between the U.S. decline and the rise of China is the main strategic problem for the United States. The great debate within the imperialist establishment, which has again revealed its cracks with the crisis of the Afghanistan withdrawal, is whether the image of retreat will end up encouraging not only the adventures of terrorist groups but will also raise the confidence level of rival powers.

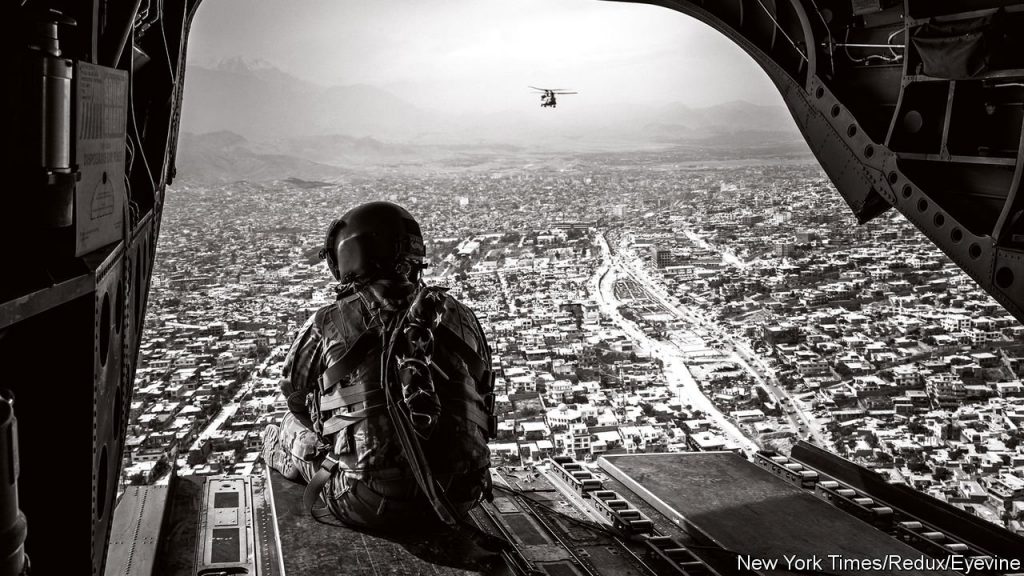

The image of hundreds of desperate Afghans hanging from the landing gear of U.S. planes at the Kabul airport is already a trademark of the Biden presidency, just as the failed attempt to retake the embassy in Tehran was Jimmy Carter’s and the evacuation of Vietnam belonged to Gerald Ford.

At the international level, the effects of the imperialist defeat in Afghanistan are twofold. First, it has exposed the enormous hypocrisy of “humanitarian interventions” as a cover for imperialist wars. This is pointed out quite clearly by the Afghan feminist organization RAWA (Revolutionary Association of Women of Afghanistan), which has issued a call to confront the Taliban and the “warlords” from a clearly anti-imperialist perspective. The second is that it has reenacted the conclusion sown by Vietnam: that the United States is not invincible, despite its enormous military superiority. That is of tremendous strategic importance for the struggles of all the workers and oppressed peoples of the world.

First published in Spanish on August 22 in Ideas de Izquierda.

Translation by Scott Cooper