Photo credit: 20th Century Fox

The Black Panther Party for Self Defense, known by every Black Lives Matter activist, has now reached the ears and eyes of millions of moviegoers through “The Hate U Give.” Names we recite after every new instance of police murder—Sandra Bland, Eric Garner, Emmet Till—aren’t forgotten by the film’s writer, Audry Wells, and its director, George Tillerman Jr., who skillfully include their images. But “The Hate” is not just a film for activist consumption. It is a touching story about family, identity, coming of age and, yes, resistance.

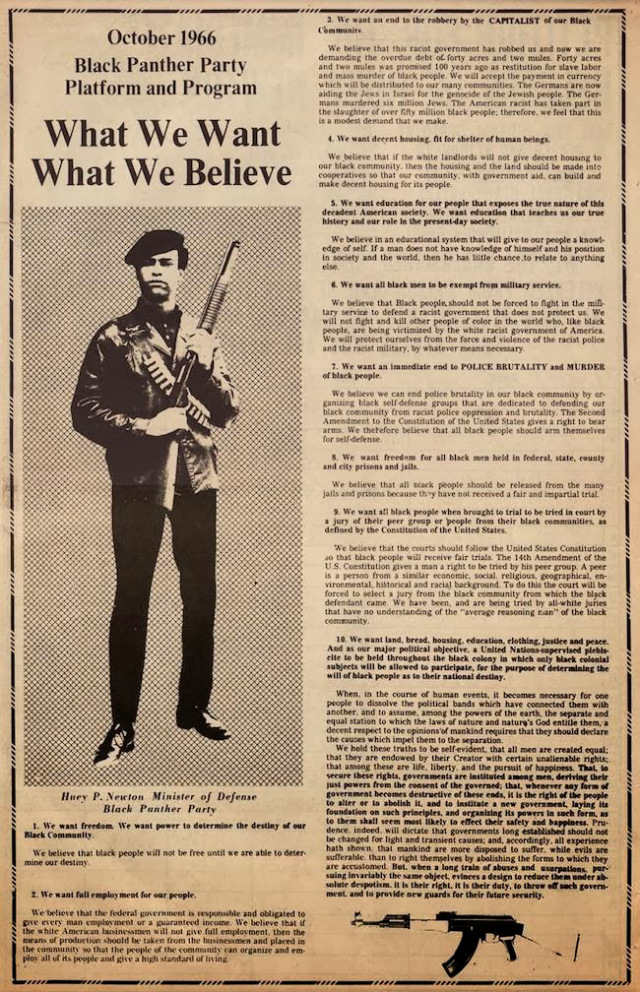

From the first scene, “The Hate” zooms in on the intensity of life for black Americans. Starr Carter, the teenage protagonist, remembers her dad, Maverick, giving her and her two siblings “the talk.” With slow, deliberate intensity, Maverick explains how to behave in the presence of police in order to stay alive: Don’t argue, hands on the dashboard, don’t make them nervous. Maverick then hands 10-year-old Starr and her younger brother, Seven, copies of the Black Panther Party’s 10-Point Program, telling them to memorize it as if it were their bill of rights. Later in the film, the Panthers’ program reappears when Maverick uses it as a tool for helping his children overcome fear and fight for their own liberation.

Fast-forward six years: Starr, now a 16-year-old, attends Williamson, a predominantly white, elite private school where she has white friends and a white boyfriend. The Carter family still lives in the black Garden Heights community, where Maverick owns a small store and Starr’s mother, Lisa Carter, works as a nurse. The film explores the pressures to “act white,” or to “act black.” While the white teens at Williamson listen to rap and talk in slang, appropriating whatever is in vogue, Starr consciously conceals anything that might get her labeled “ghetto.”

At a party, Starr reconnects with her old friend and sweetheart, Khalil Harris, before they have to flee together from gunshots. En route to Starr’s home, Khalil explains the relevance of Tupac’s music, which he still listens to. “The hate you give newborns fucks us all,” he says, because people move through life filled with rage. This is where the film takes its title from—an idea abbreviated as “THUG.” Indeed, American society continues to be wracked by violence, much of which can be attributed to deep-going alienation and rage instilled into millions of young people by a system that doesn’t value communities that are too poor, or too black.

In only a short span of minutes, Khalil’s character takes on an endearing warmth. And his bright spirit is extinguished even quicker by the multiple bullets of a white cop with an itchy trigger finger. When the cop pulls Khalil over for no apparent reason, Starr knows how a black person is supposed to act to stay safe—Khalil doesn’t. And when he takes out a hair comb, the officer shoots him dead, thinking the comb is a gun.

After Khalil’s death, a telling dialogue takes place between Starr and her ‘Uncle Carlos’, who is a police officer himself. She presses him about racial profiling, about whether he would shoot first had it been a white neighborhood. ‘Uncle’ Carlos cares deeply about Starr and admits to her that it would be different had Khalil been white. Even the “good cop”—the black, family-oriented officer—must acknowledge the racist reality of policing.

The plot follows Starr’s traumatic journey as the sole witness of Khalil’s murder as she must prepare to testify before a grand jury while trying to retain the semblance of normal life. When the grand jury fails to indict the officer for Khalil’s murder, Starr joins the protests in righteous indignation, addressing the crowd with a bullhorn. When riot police attack, Starr throws a teargas canister back at the cops. “The Hate”

Revival of Radical Black Film

In in the era of Trump— when immigrant toddlers are ripped from their parents and locked in cages; an era of anti-Muslim backlash, of anti-labor, anti-women and anti-black attacks—visual art helps shape popular sentiment on all the big issues. While much of Hollywood’s productions distract viewers from the depressing reality of economic and spiritual insecurity common in the United States, films like “The Hate U Give” provide a source of inspiration, a call to action not just to protest, but to think, to face reality as it is and try to change it.

“The Hate” avoids the clichés that ruin many otherwise good movies. An array of dynamic, flawed, relatable characters populate the narrative, moving us to smile, laugh, cry and question.

Like Boots Riley’s semi surreal “Sorry to Bother You,” “The Hate U Give” exposes the role of police as a force for repression—not protection. The two films, each in their own way, represent hard-hitting critiques of American society, illuminating the intersections of race, class, power and resistance. If the former succeeded as “The Best Pro-Union Movie to Come Around In Years,” “The Hate” brings to life the militant struggles against police terror that erupted in Ferguson, Baltimore, and beyond. Each film in its own way challenges liberal assumptions and sensibilities: We do not need more black police; we need liberation from police-state violence. Black people don’t need to integrate into the high echelons of whiteness and class privilege—they need equality and unions.

If there is a political shortcoming to “The Hate,” it is the film’s ending. Whereas most of the film builds in the viewer a sense of rage at the continuing injustices faced by black America, the ending lessens that rage with a happy ending: gang leader King goes to jail, and the Carter family rebuild their lives in seeming harmony and peace. The ending pivots attention away from the role of the police as enforcers of a fundamentally unequal social system. Though the early part of the film explores the social conditions that push people into the drug economy, King’s downfall is portrayed as a new chapter for the black community, as if the poverty and oppression that gave rise to King in the first place won’t be replicated.

Despite some shortcomings, “The Hate U Give” is a hard-hitting, inspirational call to arms—essential viewing for all opponents of police brutality and racism. It joins a number of other radical films of recent.

The 2013, “Fruitvale Station” gave a fictionalized, sympathetic look at the life of Oscar Grant, the young black man who was shot in cold blood by a cop in Oakland on New Year’s Eve 2009. In addition to camera footage from Grant’s murder, the film ends with imagery of the powerful and politically active ILWU Local 10 dockworkers’ union joining protests against police terror.

Nate Parker’s 2016 “Birth of a Nation” gave a highly sympathetic treatment of the historic 1831 slave rebellion, the largest of its kind until the Civil War. In the film, Nat Turner, a literate slave who could quote scripture and preach, was used by the plantation owners to pacify rebellious slaves with quotations from the Good Book. But Turner’s religious message increasingly placed the slaveholders in the devil’s camp. Turner organized fellow slaves to rise up and kill the masters—perhaps inspired by the Haitian revolution.

Such films cut deep into the morass of American hypocrisy and suggest the need for real social and class struggle. Slave rebellions, union drives, urban uprisings against police terror—this is the stuff of radical film.