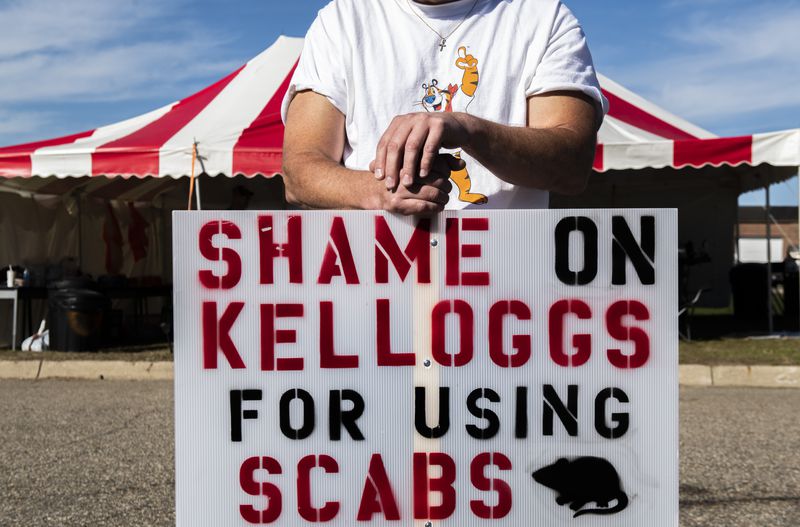

Thousands of workers are on strike right now in what’s being dubbed “Striketober.” As always, bosses are using “scabs” to cross picket lines and keep the profits flowing.

Earlier this month, about 1,400 Kellogg’s workers across the U.S. walked out. The bosses didn’t sit on their hands — they bussed in scabs to take the strikers’ place.

Months before, on March 8, hundreds of nurses walked off the job and struck St. Vincent’s hospital in Worcester, Massachusetts. That strike is in its seventh month — in part because scab nurses have taken on the work of the strikers.

At the start of the year, 1,400 workers went on strike at Hunts Point Market in the Bronx. The bosses hired private security guards and marched scabs inside to try to keep the market moving. When some of the strikers tried to stop traffic into the market, they weren’t just beaten back by the police. Union leaders themselves told rank and filers to stand down and let scabs enter.

Scabs, in other words, are the strikebreaking workers that bosses use to cross picket lines and keep workplaces running during a strike. Or as Jack London put it, “A scab is a two-legged animal with a corkscrew soul, a waterlogged brain, and a combination backbone made of jelly and glue. Where others have hearts, he carries a tumor of rotten principles.”

Why are scabs allowed to take over when workers go on strike? And what can be done to stop them?

Scabs and Worker Power

To understand why scabs are allowed to help undermine strikes, we first have to understand this: a strike is one of the most powerful weapons that workers have against their bosses.

That’s because all of the bosses’ profits come from their workers. We work 8, 10, 12, or — in the case of workers at Kellogg — 16 hours a day, making burgers, delivering dinners, treating patients, teaching students, driving trucks. All that work — every burger made, every student taught, every truckload delivered — produces a mass of money that the bosses take as their own.

Out of all that money, the bosses give only a sliver back to the workers as their paychecks. Then, some goes to pay bills or taxes — though the biggest corporations often pay little or no taxes. Everything else is “their” profits. Bosses reinvest some of this to make their businesses bigger or faster. The rest they pocket — for example, to build themselves a new rocketship.

When workers refuse to work, they shut off the source of the company’s money. But if some workers can be tempted to cross the picket line — either workers in that workplace or those brought in from outside — then workers’ leverage is compromised: profits can keep flowing. Instead of a strike being a powerful direct action shutting down the flow of profit, it can easily become just a symbolic gesture that stretches on for weeks or months, winning far less than workers could with their full leverage.

So why do many union leaders tell rank and filers to let scabs pass through a picket unscathed?

Scabs Weren’t Always Treated with Kid Gloves

First, scabs are usually protected by cops or private security, like at Hunts Point. For example, cops make sure roads and entrances stay open, and they beat and arrest union members who try to stop scabs from entering a workplace. This is just more proof that cops aren’t workers, they’re the enemies of the working class.

Second, if bosses have to bring in scabs from outside a workplace, they will probably be far less efficient than the union force, since they won’t know the workplace and machinery as well. In other words, they won’t be as good at generating profits for the bosses. So union leaders will sometimes say that letting scabs through is a calculated move to show the value of the workers standing outside.

You might be interested in: What Are Unions and Why Do They Matter?

But still, even less efficient scabs are a threat to a strike. They undermine worker power because, to some degree, they help keep the bosses’ profits flowing. As a strike drags on, the scabs can learn how to work faster and more efficiently.

But when workers are organized enough to stop scabs, then cops, private security, and bosses are made helpless. U.S. history alone is full of examples of that kind of organizing:

Minneapolis, 1934: teamster truck drivers formed “flying pickets,” or caravans of vehicles to stop, and intimidate, any non-union workers trying to help the bosses ship goods and break the strike.

Harlan County, 1973: miners went on strike, and the bosses called in scabs to take over the work. Then the Women’s Club stepped in and, as the New York Times reported:

[T]he women began “whopping” the nonunion workers. They even beat up a state trooper, and several times threw themselves in front of the workers’ cars so they couldn’t cross the picket lines.

And in 2011, striking Verizon workers and their allies found their own answer to the scab problem. Friendly UPS drivers double parked in front of the vans scabs were driving, blocking them from entering the workplace, and picketers would stake out the bottom of telephone poles or the manholes where scabs were working. Workers coordinated on Twitter to find and harass the strikebreakers.

But this kind of thing rarely happens these days. If strikes are the main leverage of workers for better pay and working conditions, why are scabs usually treated so lightly?

Roots of the Problem: Democrats and Union Bureaucrats

A major part of the answer to these questions lies with our union leaders — and the failed union strategy they have clung to for decades.

The late 1960s through the 1970s were a high point for worker struggle in the U.S. — part of a major uptick in worldwide class struggle in previous decades. In just one year — 1974 — workers held more large strikes of any period on record since the 1950s.

But the tide of struggle receded. The ruling class saw its chance, and it went on offense. Among other things, they started a multi-decade assault on unions. We see proof of that attack ranging from Reagan’s mass firing of striking air traffic controllers in 1980 to the more recent Janus decision by the Supreme Court, which made it harder for unions to collect dues from their members.

The response by union leaders across the country — like those of the AFL-CIO union federation — was to cozy up more and more to the Democratic Party. The idea was that if they worked hard to get Democrats elected, including donating large amounts of dues money into their campaigns, they’d be rewarded with laws that would bring back the union movement.

But this strategy was a deal with the devil — it meant that unions should “play nice.” Strikes can be hugely disruptive to an economy, something Democrats hardly want since they’re usually funded — and far better — by CEOs and corporate lobbyists. So “strike” has become a dirty word for most union leaders. It’s no coincidence that the number of strikes plummeted over the years. 1985 saw 54 large strikes — rounding up, that’s 13 percent as many as in 1974. 1995 had 31. 2017 had just 7.

More than this, in recent years, when strikes do happen, they almost only come after a contract runs out, but hardly ever in the middle of a contract. This is mainly because it is standard business for union leaders to sign contracts with “no strike” pledges in them, voluntarily giving up their biggest weapon to the bosses. In fact, in states like New York, the Democratic Party in charge there has made it illegal for public sector workers to strike.

For most union leaders in recent years, in other words, being friends with Democrats means abandoning the strike.

Allowing a “no strike” pledge in a contract, and holding members to it, is disastrous. It means that union leaders have to be the “economic police” that stop workers from fighting with one of their primary weapons, the strike, when the bosses invariably break the law and attack workers even more than usual.

And these kinds of contracts — and the union leaders enforcing them — try to keep workers on the sidelines when a new upsurge of mass struggle happens. We saw signs of this in the summer of 2020 during the anti-cop uprising, one of the biggest social protest movements in the history of the United States. The number of unions who went out on solidarity strikes against cops was extremely low, though there were some limited exceptions, like the ILWU. This, despite the fact that cops aren’t just racist murderers — they’re the bosses’ shock troops for breaking strikes, protecting scabs, and beating workers standing on picket lines.

And in addition, union bureaucrats often live in a different world than the average worker. Their paychecks often depend on dues money, not on working a shift in a factory, school, or hospital. That means they often have different priorities than the average worker, too. The goal is typically to play by the rules — that is, to make sure that any strike follows the law to the letter — for fear that they or the union will be censured or they will be arrested. But the simple truth is that there is no such thing as an illegal strike — only a strike that’s not powerful enough to win.

To bosses, the weak set of laws protecting unions are just temporary obstacles. We saw clear examples of this when Amazon fired workers trying to create a union, and harassed workers with anti-union propaganda at work and beyond. These are all part of a wide array of legal, semi-legal, and illegal tactics to stop union organizing.

All of this means that union leaders usually make sure scabs can cross a picket line. Part of the reason there are so few strikes is because the leadership knows that if you refuse to stop scabs, there’s a very good chance the strike will fail.

But this strategy by our union leaders — cozy up to Democrats, stop striking, play nice to scabs — has been a miserable failure for the working class.

We see this failure reflected in the numbers. Not only have the number of strikes cratered, but the number of new union elections has plummeted as well. So has the percentage of workers protected by a union: that number is hovering at just 11 percent. In the private sector it’s just 6.

Meanwhile, legislation to make it easier to unionize was tossed in a drawer by former president Obama and, now, President Biden. Those are the laws that unions thought they were buying by giving money to Democrats. To be sure, the Democrats did give minor concessions to unions, but hardly enough to make a real difference. Even bigger concessions, if they happen, can only foster a dangerous illusion: that worker power comes from the same Democrats that protect the interests of the bosses — not workers fighting for themselves. It’s no coincidence that Biden carried the billionaire vote in 2020.

What Do We Do about Scabs?

Playing nice doesn’t win a strike. And if the last forty years are any indication, it won’t revive the union movement, either.

Winning strikes decisively, squeezing fundamental concessions around pay, hours and conditions from bosses, means stopping scabs — just like Verizon workers knew in 2011, and like the Teamsters knew in 1934. That means finding ways to intimidate these strikebreakers, blocking their vans and trucks, clogging the roads into the factory, and so on.

This doesn’t just mean organizing one’s own coworkers in a strike to stop scabs. It also means the kind of real solidarity between rank and filers in different unions — workers ready to get on busses and reinforce others’ pickets, building up the power to intimidate and stop scabs. This would have a much greater impact than lobbying Democrats.

But the union leaders who have been failing the union movement for decades will rarely help with this key task. Instead, they’re often an obstacle standing in our way, because they’re more worried about playing by the rules for their Democrat friends than winning the strike.

So stopping scabs will mean exercising real power from below — in real union democracy like worker assemblies right there on the picket line, or anywhere rank-and-file workers can figure out for themselves what they ought to do, and how they ought to do it:. This includes how to get the biggest numbers out on the picket line, how to creatively scare off scabs, and how to stop profits from flowing to the bosses.

But one other key part of stopping scabs is convincing them to join the strike. Oftentimes, scabs are the most demoralized parts of the working class, convinced by decades of union decline that there’s little a strike can win. And potential scabs can even be part of the same workplace, or even the same union; people considering breaking ranks with their union siblings. Real union democracy, like mass assemblies, as well as picket lines are crucial also for winning over scabs and building up the ranks of the strike force. Though at the end of the day, the most convincing argument is solidarity and power: building the kind of cohesive, determined strike movement and picket lines that will make life much, much harder for scabs.

There will be plenty of opposition from our union heads, who will wring their hands and worry what the Democrats will think. But forty years of losing show that the Democrats aren’t our allies.

With thousands on strike across the country, we might be seeing signs of an upsurge of union struggle today. The power of our unions comes from the fact that all profit comes from workers. Stopping scabs is a key way to use that power.