In the 1870s, with the growth of its working class, Germany faced a profound shortage of available housing for workers in the country’s industrial centers. The crisis launched a debate within the workers’ movement, and in June 1872, Friedrich Engels entered the fray. In a series of articles published over the next eight months, Engels spelled out his views on the housing question, which later became a pamphlet. As he wrote,

It is not that the solution of the housing question simultaneously solves the social question, but that only by the solution of the social question, that is, by the abolition of the capitalist mode of production, is the solution of the housing question made possible.

This profound statement applies well beyond access to housing, encompassing everything workers need to live in cities: transit, schools, health care, and even parks and recreation. Those who control a city’s wealth ultimately make the decisions, inevitably within the framework of capitalism — which means that whatever is built should serve the interests of profit, whether directly or indirectly. And even if they pay lip service to community involvement in those decisions, they reserve for themselves the final say.

The results have often been devastating for city dwellers, and they have sometimes provoked radical responses. Housing figured in the famous 1912 Bread and Roses strike of textile workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts. It was a pay cut that finally sent workers out onto picket lines, but substandard housing was a central issue, too, along with devastatingly high infant and child mortality rates that could be linked to worker necessities.

Capitalism is driven by an internal law that dictates bosses should try to pay only what is absolutely “necessary” for workers to “re-create” their labor power so they can come to work each day. Hence, the starting point for wage slaves is money for the most basic needs: just enough to put food on the table, but only enough not to starve; a minimal amount of clothing; and housing that is merely sufficient for protection from death. Some capitalists figured out over time that workers who freeze and die in unheated tenements or who are bitten by rats in their sleep might not be back at work the next day. It’s not those conditions they care about but whether wage slaves are back on the job tomorrow.

Anything above and beyond subsistence has always been a conquest of the working class. Direct conquests come from striking for higher wages. Indirect conquests come when the ruling class realizes that, say, a park makes for happier and thus more docile workers — so let’s give them one. Again, the ultimate interest is profit making.

Cities, though, are not just places to “store” workers. In The Right to the City, Marxist economic geographer David Harvey explains that urbanization — and the lifestyle transformations that accompany it — is a further mechanism for the bourgeoisie to extort surplus value from goods and services. Rather than make urban living any more survivable for the working class, the capitalists have often focused on ways to bring people into the city from outside to spend money, rather than investing in public transit for residents. Further, as spending and consumption rates get driven upward, speculation creates artificially high property values in centrally located urban neighborhoods. This impels capitalists to evict those already living there or to tear down buildings, so they can “redevelop” and rake in even more money.

Whether through gentrification, redlining, or direct segregation, the capitalists have consistently relied on racial divisions to thwart class solidarity. The most destructive consequences of their actions have always harmed the most exploited sectors of the working class.

The bottom line is that everything the capitalists do to develop cities, from housing to shopping to recreation, ultimately aims to support their economic and social interests — even when these things appear to be good for the working class.

Company Towns

Perhaps nothing encapsulates this, especially but not exclusively in the realm of housing, than the historical “company town” in which all the housing is owned by the main employer of those who inhabit the domiciles. Most or all places where goods can be bought by residents are also owned by the company. The result is that the money paid to the worker is taken back by the company through rent and store purchases (often at jacked-up prices). Talk about wage slavery!

At one point, some 3 percent of the U.S. population — mostly workers in the coal, steel, and lumber industries — lived in more than 2,500 company towns. Housing was typically just adequate; in Segundo, Colorado, for instance, it lacked indoor plumbing.

These towns no longer exist in the same way they once did, although there are a number of unincorporated municipalities wholly owned by large corporations. Just this March, Elon Musk announced plans to incorporate a region of Texas, where his SpaceX rocket-manufacturing and launch facilities are located, as the city of “Starbase” — as a sort of company town.

Some “enlightened” capitalists built “model” communities for their workers to provide a modicum of stable residential existence — an investment in labor peace at a time of union volatility. Pullman, Illinois, a famous example, was built just outside Chicago in the 1880s to house workers of the Pullman Company, which made railroad passenger cars. Some 12,000 employees and their family members lived in the entirely company-owned town, which had markets, a library, churches, parks, and entertainment facilities. You could work for Pullman and not live there, but it was strongly encouraged — and resident workers were treated better at the factory.

When an economic panic hit in 1893 and demand for Pullman cars declined, the company cut workers’ wages and hours while refusing to lower rents or prices in the shops. This provoked a nationwide railroad strike. Later, a national commission blamed Pullman’s paternalism for the strike — workers, who had no say in town affairs, felt as if they lived in a dictatorship — and rather ironically called it “un-American.” The economic hardships Pullman forced onto its workers were counterposed to the idyllic nature of the town itself in the commission’s report:

The aesthetic features are admired by visitors, but have little money value to employees, especially when they lack bread.

Eventually, the company was forced to divest its ownership of the town, which has since been annexed to Chicago. The entire episode speaks to the real underlying motivation of the “enlightened” George Pullman.

More common than the company town are the post–World War II projects that often combined housing and transportation and almost always devastated working-class neighborhoods.

Highways Destroying Neighborhoods

The 1949 Housing Act ramped up a massive federal “slum clearance” process that had been kick-started by the New Deal, with the goal of “urban renewal” and “development” — cringe-worthy euphemisms for displacing the working class to further capitalist interests. From 1953 to 1986, the federal government spent $13.5 billion on these projects — to which state and local funds were added.

This government-backed process of dispossession was the context of the famous fight between Jane Jacobs and Robert Moses over the construction of a road through New York City’s Greenwich Village, about which much has been written, cartooned, and even set to music.

The story is celebrated for many reasons. Jacobs, a community organizer, fought the top-down approach to urban planning that Moses epitomized. He tried to push through his plans for a highway cutting straight through Washington Square Park, while Jacobs documented the false narrative that condemned areas classified as “blighted,” showing instead a thriving neighborhood. She rallied people to a campaign against Moses’s plans for the destructive project. While Jacobs was never explicitly anti-capitalist, her battle for pedestrians over cars has come to symbolize the fight for people over profits.

The idea of transforming the urban environment into an oil company CEO’s fantasy began in the early 20th century. The Great Depression demonstrated capitalism’s precarity, and the working class was organizing en masse into labor unions. Franklin D. Roosevelt, elected in 1932, aimed his New Deal programs at stabilizing capitalism, proclaiming in a 1936 campaign address to business leaders, “It was this Administration which saved the system of private profit and free enterprise.”

It would take World War II to mobilize the economy back to what it had been before the Depression. Business leaders and politicians were planning to expand their stagnating markets to occupy new spaces. Rapidly expanding urban living beyond the city limits, to “suburbs,” was key — and so was the automobile. Auto companies secretly helped destroy the streetcars in Los Angeles that working-class people depended on to push the development agenda (a history underlying the 1988 film Who Framed Roger Rabbit?).

Moreover, as cities became more racially diverse, the creation of suburbs and highways also allowed white people to work in cities without having to live in them. They took their money with them to the suburbs. Different areas of the cities could be left to rot or be redeveloped for profit making. The Black and Brown communities that remained would have to fend for themselves.

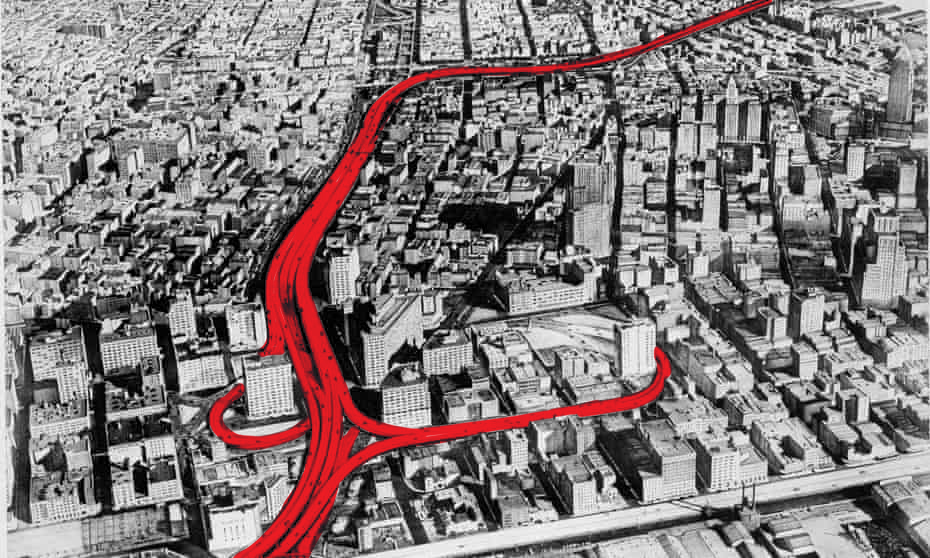

It is no mystery what might have happened if Jacobs’s people power hadn’t saved Greenwich Village. We do not need to look further than the Cross-Bronx Expressway, just a few miles north, to see how capitalist “development” projects can destroy the fabric of a neighborhood.

The Cross-Bronx Expressway is just seven of the hundreds of miles of highways Robert Moses created as New York City’s “master builder.” In 1945 he had proposed a six-lane highway to run through the center of the borough — no easy feat, especially with East Tremont right in its path. It was a lively working-class neighborhood full of shops, good jobs, and good schools, largely populated by recent Jewish immigrants who had fled the war in Europe. Its Crotona Park had tennis courts, baseball diamonds, playgrounds, and even a pool built by Moses during the Depression. The community was a place where residents interacted, built nest eggs, and created lives. Over the years, more Black and Puerto Rican families moved into the area; the Jews of East Tremont stayed.

To build the Cross-Bronx, Moses would have to evict “tens of thousands of protesting voters, demolish those homes, tunnel under or cut across subway lines, elevated railroads, sewers and water mains. … A single extra foot of width would require thousands of evictions.” In December 1952, Moses sent eviction letters to East Tremont residents. There were 54 spacious, affordable apartment buildings and 90 family homes, housing 1,530 families, along with 60 stores in the path of the expressway’s “bulge.”

There was opposition, mostly from housewives led by Lillian Edelstein. They proposed a well-researched, cheaper, and less destructive alternative route running along the northeastern edge of Crotona Park. Moses, unaccountable to the community, gave it barely any consideration.

East Tremont was not the only neighborhood affected. Many residents in other neighborhoods had no choice but to accept squalid temporary relocation before they faced an increasingly expensive housing market. This dispossession illustrates the false “choices” capitalism presents to those of us not in the owner class — more accurately described as coercion. Working-class people, especially those living below the poverty line, must make decisions based on immediate needs, not long-term asset evaluations. The system is designed to make taking a pittance of relocation money offered the only “choice”; a long, expensive legal battle is rigged against the majority.

Today, the largely Black and Brown communities that live along highways like the Cross-Bronx are subjected to intense air and noise pollution and the chronic health problems those bring — even exacerbating the impact of Covid-19. Because housing is cheapest where exposure is the greatest, the most vulnerable sectors of the working class continue to suffer from urban planners’ undemocratic, profit-driven decisions of more than half a century ago.

New York City wasn’t the only place with proposals for highway construction that would destroy neighborhoods and displace residents. Boston’s example is the Inner Belt.

Boston, bordered on the east by Massachusetts Bay, has just outside its city limits the famous Route 128 (officially part of I-95, which runs from Maine to Florida). It is a circumferential route, eight lanes in some places, through abutting suburbs. Route 128 is like Washington, DC’s Beltway, but thanks to the ocean it cannot complete a full circle. It also requires drivers to go around, rather than through the city, when traveling north-south.

Beginning in the late 1940s, planners were developing an idea to build a massive highway through the heart of Boston. The capitalists desperately wanted this route to save time and money getting goods to the population center. The plan really picked up in the 1960s — and people organized to stop it.

Construction would displace 7,000 people from their homes, and the massive highway and new feeder roads and intersections would gut two largely Black neighborhoods: Roxbury, on the Boston side of the Charles River, and Central Square, across the river in Cambridge, between Harvard University and MIT. Because it was so big and would separate people, it was called the “Chinese wall.”

Boston is a city of neighborhoods, a walking city, and its gridless center comprises mostly one-way streets that follow colonial-era cow paths.

The plan sparked immediate condemnation from community leaders. There were lots of protests over many years. On a very cold day in January 1969, more than 2,000 people stood on the steps of the Massachusetts State House in Boston, blocking the entrance and demanding that the governor cancel the project. He ended up issuing a moratorium the next year against any highway construction inside the Route 128 loop, and the Inner Belt project was canceled in 1971 — but not before swaths of Roxbury had already been razed to make way for the highway.

To this day, you can still find “Stop the Belt” signs in windows of old apartments or painted on the sidewalks. But the Inner Belt was squashed because people organized, people who had never been invited into the decision-making process before the plan was announced — and they won.

One Boston neighborhood was already under attack before the Inner Belt was proposed. The highway would have gone right through it.

Urban “Blight”

But for two largely hidden signs, Boston’s Government Center, a giant development in the city’s downtown area, reveals nothing about the neighborhood that gave its life for the city hall, federal buildings, and a desolate, wind-swept concrete plaza (typically quite empty) that occupies the space. Below ground, in the subway stop, there is an old tile wall sign with a hint, and one small pub on a side street still bears the name of that once vibrant neighborhood: Scollay Square. Readers of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road might not know that his reference was to a real place.

Scollay Square (also known as the West End) is an example of what happens when the governments that serve capitalism’s interests make decisions on its behalf with no regard for the consequences for most people.

Beginning in 1838, Scollay Square became one of Boston’s most important commercial and cultural centers, but also a thriving working-class neighborhood. Because of its prime location, it was the scene of some notable historical events. There, William Lloyd Garrison published the Liberator, the nation’s most important abolitionist newspaper, and he was attacked by pro-slavery mobs twice in the square, setting off a debate that turned Boston into the center of the anti-slavery movement. In 1853 the famous free Black abolitionist crusader Sarah Parker Redmond — 102 years before Rosa Parks did something similar on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama — undertook her first act of civil disobedience at the Old Howard Theater when she refused to move to the “Black” section from the seat she had purchased. The square had multiple hiding places that were part of the Underground Railroad.

Over a long period, though, Scollay Square declined and became “seedy.” The theaters became burlesque establishments. Buildings fell into disrepair, including the apartment buildings that housed thousands of workers. In the early 1950s, spurred in part by the Housing Act of 1949, the city began to think about acquiring federal loans to clear out the “slum” and sell it to private developers.

The legislation was supposed to encourage building new, better housing, but Boston leaders had other ideas. The city wanted to remove lower-income residents and make way for new development with no housing. On April 25, 1958, people received their eviction letters, and soon thereafter the entire area was razed to the ground.

Scollay Square, though, was not a slum. In the interest of wealthy developers, though, the city worked hard to amplify the slum narrative. Garbage collection was halted for a time to help create a mess that could be seen in news photos. Michael Jones, in his 2004 book The Slaughter of Cities, recounts that one Boston newspaper sent a photographer to overturn a trash can on a West End sidewalk and take a picture.

Over the next decade, an entirely new “neighborhood” was built, one consisting of city, state, and federal buildings — Government Center.

In the end, some 20,000 residents were displaced. About a third were relocated to substandard housing far from the West End — at much higher rents. The rest had to fend for themselves. There were long-term mental health problems and even suicides. In 2015 the city’s redevelopment chief issued an official apology for the demolition of Scollay Square. Touted as “urban renewal” — a term that first appeared in the United States with the newer Housing Act of 1954 — the new Government Center included not a single room of “housing.” Its builders won highly lucrative government contracts, and some of Boston’s wealthiest construction moguls today cut their teeth on the project.

“Community Control” — or Socialism?

Imagining alternatives to capitalist hegemony over the daily lives of workers easily leads to the notion of community control. Institutions, after all, should be controlled by the people most impacted by them. Yet under capitalism, “community control” becomes a rhetorical veil draped over decisions that have already been made. While the capitalists and their politicians serve up appeasement tactics such as advisory boards, public hearings, and participatory budgeting, they are largely window dressing. Participatory budgeting in New York City, for example, gives citizens a say over a meager $1 million per district — and only if their district’s city council member decides to opt in to the program.

This sort of “community control” aims to placate the public. It resembles the co-optation of social movements into Democratic Party electoral campaigns; both help consolidate capitalist control and dilute proletarian power.

By demolishing neighborhoods, relocating residents, and building on a “clean slate,” the capitalists look to expand their profits, directly or indirectly. The working class and its most marginalized sectors bear the brunt of capitalist “development.”

Today, even some Democrats scorn the brutal history of urban renewal and so many U.S. highway projects. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg recently told the Grio, “There is racism physically built” into highways, a nod to the larger patterns in our examples. He touts the Biden administration’s Justice40 Initiative, which aims to direct “40 percent of the overall benefits of relevant federal investments to disadvantaged communities.”

One approach for stitching once-divided neighborhoods back together is highway removal; dozens of such projects are currently underway nationwide. Even when progressive, though, the community-centered rhetoric around these projects and proposals — and even community involvement — masks the profit motive, which is always the bottom line in the capitalist framework. No wonder there is so much concern about what development projects will be built where these bulldozed highways once stood.

Harvey, echoing Engels, asserts that in addressing the “housing question,” the capitalists only displace — but never eliminate — the conditions that created the initial problem. So too with highways. He calls this process “accumulation by dispossession,” and it is fundamental to understanding urbanization under capitalism.

The bedrock of a socialist program is democratic rule by the working class — in other words, community control. But under proletarian governance, that control would not be patronizing and piecemeal. Rather, the proletariat would democratically decide on everything city dwellers need, from health care, housing, and education to production and self-defense.

We need to fight for that more expansive vision of community control — beyond schools and most certainly beyond the police — along with a militant plan to make it possible. That will require the self-organization of the working class. In his timely 2008 essay, Harvey writes,

The right to the city is far more than the individual liberty to access urban resources: it is a right to change ourselves by changing the city. It is, moreover, a common rather than an individual right since this transformation inevitably depends upon the exercise of a collective power to reshape the processes of urbanization.

As Engels forcefully asserted nearly 150 years ago, the housing question — indeed, all the problems that beset the working class living in cities under capitalist rule — cannot be solved absent the socialist reorganization of society.