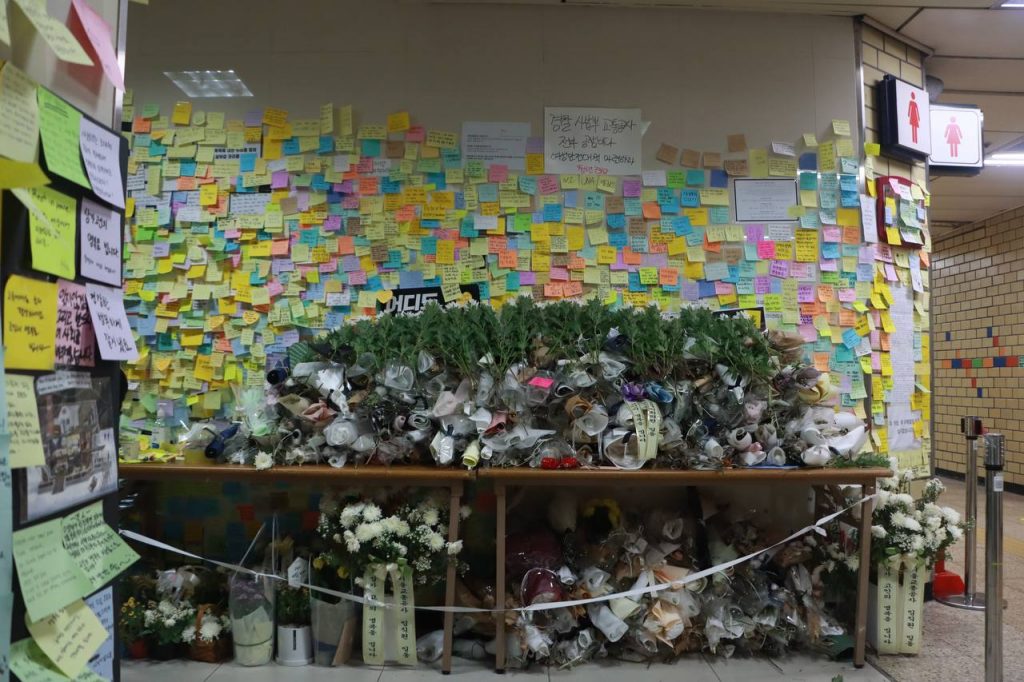

On September 14, Sindang Station, Seoul, was the site of a brutal femicide against a woman who worked for Seoul Metro. The rail company labels all its women’s restrooms with the slogan “A restroom where women are happy,” but its policies and workplace conditions put women workers in danger.

The woman and her killer, Jeon Joo-hwan, joined the company at the same time. Jeon had stalked his coworker continually since 2019. The victim filed a complaint with the police, but the court rejected the arrest warrant. She filed a second lawsuit for stalking. In the second case, the police did not ask for a warrant. Police protection measures were put in place but were limited to one month. Joen underwent trial proceedings, but he was not detained, and no safety measures were taken to protect his coworker.

Seoul Metro removed Joen from his position, but left his access to the company’s computer network, which he used to track his victim’s movement while she was at work. Eventually, the victim woman was killed at work.

The South Korean state and Seoul Metro made this femicide possible. Every day, the state turns its back on violence against women, while courts ignore appeals of women seeking protection. Seoul Metro prioritizes profit over implementing measures to eradicate sexual violence. Korean media reported that many of Joen’s coworkers called him “a good person,” an expression of rising anti-women sentiments among right-wing elements of Korean society.

Violence against women is common in South Korea. According to a survey on the topic, 57.8 percent of women answered that they felt vulnerable to misogynistic violence. The Ministry of Gender Equality and Family quietly published these results in August 2021. Eighty percent of violent crime victims in South Korea are women. Korean media reports that a women’s rights group, Korea Women’s HotLine, found that in at least 83 Korean femicide cases, women were killed by men whom they had close relationships with. These alarming statistics come six years after the high-profile murder of a woman at Gangnam Station.

As such violence spreads, the Minister of Gender Equality and Family claims that it will prevent such violence and create a society where women are safe. The prime minister said he would come up with strong measures to prevent the recurrence of femicide. But this same prime minister and the president say they want to abolish the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family. How can they be trusted to keep women safe?

The courts also cannot be trusted to protect women. Stalking is a typical “prediction crime” that leads to violent crimes such as murder. This time, however, the court dismissed the arrest, stating that there was no risk. The courts always show mercy or reduce sentences for crimes against women for various reasons, such as if the defendant is a first-time offender, shows remorse, has a mental or physical weakness, or agrees to make a settlement with the victim.

Workplaces Are Still Dangerous

This is not the first time Seoul Metro has been criticized for its sexual assault measures. In 2018 the company caused controversy when it appointed a manager—disciplined for sexual assault—at a workplace that was near one of his victims. In fact, it is suspected that the corporation monitored the woman who had exposed this manager’s sexual harassment and demanded follow-up measures. The corporation should have introduced proper measures to eradicate sexual violence in the workplace and protect the victim. Instead, in 2020, sexual harassment in the workplace continued to such an extent that one in five workers in Seoul Metro said that they had experienced or heard of sexual harassment. It is no wonder another woman was killed at her workplace as a result of Seoul Metro’s negligence.

Moreover, Seoul Metro has been continually restructuring and reducing the number of workers while ignoring their safety. The sections of stations and technology were integrated and outsourced. This year, as well, the company is pushing for restructuring, or “management innovation,” which will squeeze workers. The corporation does not care about workers’ right to work safely without dying. A site with a shortage of people cannot be safe. On the day of the incident, a female station worker was killed while patrolling alone.

Seoul Metro and the government, which focus only on cost reduction, cannot deal properly with the risk of sexual violence against women workers. Korean labor unions created for unity and struggle must take up the fight for workplace safety and solidarity with women. Korean workers must all fight together to end oppression and discrimination against women workers. When women workers can work safely, all workers can work safely.

Modified for clarity by Sam Carliner