In 1910, Mexico was celebrating its 100th anniversary as an independent nation. Since 1877 the country had been under the dictatorial rule of General Porfirio Díaz Mori, a veteran of the Franco-Mexican war of 1867. Through both constitutional reforms[1] and rigged elections, the dictator was reelected, governing for over 30 years (a period known as the Porfiriato or the Pax Porfiriana). His administration was known for its ruthless suppression of any political and social opposition. For example, in 1892, residents of the town of Tomochic were massacred on Díaz’s orders after they declared autonomy. Of the town’s 279 residents noted in the previous year’s census, 165 died in the violence; the only survivors were women and children. Similar violence was waged against workers.

Background of the Mexican Revolution

In 1906 miners in the northern state of Sonora went on strike, as did textile workers the following year in the coastal state of Veracruz. This was the direct background of the Mexican Revolution: both strikes were repressed ruthlessly by the government, which killed hundreds of people with the help of U.S. Rangers from Arizona acting as scabs. In 1910, on the centennial of Mexico’s independence, Díaz had the perfect opportunity to show off his government as a modern administration. He ordered the building of grandiose public works, such as the Independence Monument, the Lecumberri prison, and the Palace of Fine Arts, and he accepted gifts from foreign governments, such as big ornamental clocks from China and the Ottoman Empire.

But Díaz was old, and he knew he needed a successor, so he held elections one last time. This time, however, his opponent was the young landowner Francisco Ignacio Madero, the son of a rich family. Madero promised democratic reforms and soon grew popular among the masses with the slogan “Sufragio efectivo, no reelección” (Effective suffrage, not reelection). He ran as candidate of the newly established National Anti-reelection Party.

Díaz, fearing this, ordered Madero’s arrest, but Madero fled to San Antonio, Texas, where he published a document called “The Plan of San Luis Potosí,” in which he refused to acknowledge Díaz’s election. Given that all legal options had proved ineffective, he proclaimed that, on November 20, the Mexican people should rise up and overthrow the dictatorship. Mexicans answered the call, but their effort was supported not by middle-class sectors, as Madero had initially thought, but by the popular masses of workers and peasants. In February 1911, Díaz’s troops were defeated, and he was forced into exile in Europe, where he died in 1915.

Madero’s Government and Zapata’s Radicalization

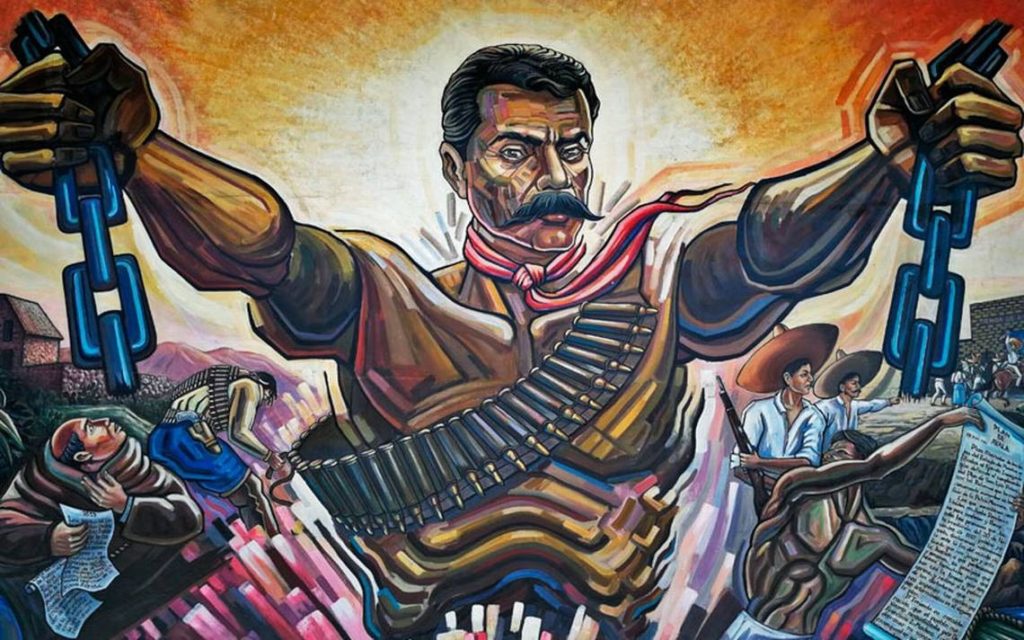

For the first time in decades, Mexicans had a democratically elected president. Madero had gathered the support of anti-reelection sympathizers, working-class anarcho-syndicalists like the Flores Magón brothers in the North, ranchers such as Francisco “Pancho” Villa in the northern state of Chihuahua, and peasants such as Emiliano Zapata in the southern state of Morelos. But Madero’s presidency left the Porfirian apparatus intact and delayed the much-awaited agrarian reform.

This particularly angered Zapata, who refused to recognize Madero for his demagoguery. Madero in turn branded Zapata a traitor and ordered the army to pursue him. At the end of 1911, Zapata and his supporters responded to Madero’s military aggression with the “Plan of Ayala,”[2] marking a break with Madero and proposing a radicalization that went far beyond the Plan of San Luis Potosí.

Articles 6 to 9 of the “Plan of Ayala” were based on two fundamental principles: First, the expropriation and nationalization of lands without compensation. This would be carried out against “the landowners, científicos[3] or leaders who directly or indirectly oppose this Plan,” targeting all landowning classes in the countryside. Second, the land would be seized by dispossessed peasants, based on the armed power of the insurgent people, and it was the landowners who would later have to prove their right to the lands before the courts, and not the other way around, as was called for in bourgeois legislation.

The “Plan of Ayala” was undoubtedly the most advanced programmatic formulation of the land question that arose during the Mexican Revolution. It gave Zapatismo a strong anti-capitalist bent. This was also expressed on the political terrain: if at the beginning of the revolution the Zapatistas allied themselves with Madero—whose program was limited to institutional reforms and who represented a sector of the ruling class—they finally broke with him and adopted an independent position, one whose basis was both the “Plan of Ayala” and the towns of Morelos, where they established their own military organization.

The Zapatistas tried to put the “Plan of Ayala” into practice during the following years, in the heat of the civil war. But it was not until 1915 when the Zapatistas’ radical agrarian policy could be broadened and deepened on a large scale. It was then that the Zapatistas and workers began constructing their own state, or what the historian Adolfo Gilly calls the Morelos Commune—echoing the Paris Commune of 1871. Like the communards of Paris, the peasants and agricultural workers of Morelos stormed the heavens.

Huerta’s Coup and the Aguascalientes Convention

Madero was a naive and superstitious man, always trusting any advice and refusing to listen to the people close to him, like his brother Gustavo. The U.S. embassy, fearing that the social discontent in Mexico would affect U.S. interests (as was the case in Cananea), plotted with Díaz’s nephew Félix and General Victoriano Huerta to oust him in a coup.

They gathered the support of conservative forces and staged battles in Mexico City for 10 days straight in what is known as the Decena Trágica (the Ten Tragic Days), killing thousands of civilians and troops loyal to Madero while he and his vice president, José María Pino Suárez, were under arrest. Huerta forced Madero to resign, and they finally transported him and Pino Suárez to the Lecumberri prison and executed them there; Madero’s brother, who had discovered Huerta’s conspiracy, also perished at the hands of Huerta’s men. Pedro Lascuráin was named interim president, and his only action during the 45 minutes of his tenure was to give power over to Huerta. This farce led those who had risen up against Díaz to take up arms once again.

This time, the revolutionary forces—joined by the forces of Álvaro Obregón, a Sonoran politician, and Venustiano Carranza, governor of the eastern state of Coahuila—aimed to oust Huerta, who fled to the United States. Zapata and Villa met in Mexico City and arrived with their forces in a five-hour military parade. They discussed their political positions and agreed that neither sought power, even going as far as to (in a Goofy Gophers-esque situation) ask the other to sit in the presidential chair, to which Villa finally agreed.

The Mexican Revolution held the Aguascalientes Convention to try to erase the differences between the two factions. Carranza and Obregón represented the interests of the Mexican bourgeoisie and urban sectors, which wanted to maintain the status quo as much as possible while abolishing the most abhorrent aspects that the Porfirian regime. Villa and Zapata, on the other hand, represented the interests of peasants, rural workers, and indigenous peoples, who sought land through an agrarian reform.

Since the factions represented interests of opposing classes and social forces, they could agree only on a new interim president. Carranza and Obregón argued that constitutional power needed to be respected, and thus named themselves Constitutionalists and their military branch the Constitutional Army. Villa and Zapata, on the other hand, decided to respect the agreements of the Aguascalientes Convention, and their faction was known as the Conventionalists.

The Morelos Commune

When the Zapatistas left Mexico City and returned to Morelos, Obregón went to war with Villa’s Northern Division. This was a wise strategy, since Villa was his most powerful military adversary, and defeating him would open the way to victory for the Constitutionalists. This decision, however, allowed Zapata and his supporters to build, throughout that year, one of Mexico’s most advanced social and political experiences, deepening what had been done since 1911 and in particular since the defeat of Huerta in Morelos.

The land distribution was carried out to return ancestral properties to their original owners through agrarian commissions, which raised the topographical plans and the boundaries of all the villages in the state, granting them fertile lands for cultivation and resources such as water wells, springs, fountains and forests.[4]

This culminated in a great social transformation: the expropriation without compensation of the haciendas and the elimination of the economically dominant class in Morelos. This also showed that point 8 of the “Plan of Ayala,” as noted above, undermined the entire landowning class. For example, “in just two months, between January and March 1915, 105 Morelos villages recovered their lands, as Zapata informed Roque González Garza, in charge of the Executive Power of the conventionalist government.”[5]

This was accompanied by the creation of a National Bank of Rural Credit, a Factory of Agricultural Tools, and Regional Schools of Agriculture. The purpose of these measures was to promote the sustainability of agricultural production by facilitating access to credit, education, and tools and by promoting the modernization of the countryside and collective planning. Although this was mostly concentrated in Morelos and the neighboring states where the Liberation Army of the South had military influence, Manuel Palafox—one of Zapata’s secretaries—used these initiatives to widen the scope of the “Plan of Ayala.” On this point, it is important to consider the Zapatista policy toward the sugar mills:

The most advanced production units in the state of Morelos, due to their technification and productivity, and their concentration of wage labor, were nationalized without payment: We are referring to the mills and distilleries…. The mills, in addition to the haciendas, were the main economic sustenance of the state…. There were 24 established mills, operating with state-of-the-art machinery and a very sophisticated irrigation system. The degree of development of the sugar industry can be measured if we consider that Morelos supplied one-third of the sugar consumed nationally, and was the third-largest sugar-producing region in the world.[6]

The development of this profound economic transformation was not devoid of contradictions. While Zapata and his associates preferred the proliferation of sugarcane production to feed the sugar mills and thus fund the “war economy,” the communities favored guaranteeing their livelihoods through production for self-consumption, a decision that was generally respected by the Zapatista high command.

The expropriation and nationalization of the haciendas and the sugar mills verified the anti-capitalist dynamic that unfolded in Morelos, a dynamic that—within the limits imposed by the economic and social structure of the state and regions—called into question the property of the former ruling class over the region’s primary means of production. The economic transformation was accompanied by a change in social relations. As an author quoted above puts it,

The expropriation and nationalization of land in Morelos had its correlate in forms of specific power that preserved the conquests and the achievement of the programmatic mandates of the Ayala Plan. According to Adolfo Gilly and John Womack Jr., decision-making and collective organization of villages served to re-create a type of democratic power in the state, which was the sustenance of the anti-capitalist measures carried out by the Zapatistas.[7]

Another author defines it as “an experience of self-government, of freedom for communities and of progress in transforming social, economic and political relations at the local level … an autonomous regional power—a regional state, in the strict sense.”[8]

The Morelos Commune and the Zapatista government[9] radically opposed all the governments that emerged during the revolutionary process: they destroyed—albeit locally—the capitalist state and its economic basis, sustaining themselves through the expropriation and nationalization of the latifundia and the sugar mills. In addition, peasants and agricultural workers, nourished by their own forms of organization, built their own power. To note this, as well as the revolutionary character of Morelos insurrection, does not deny their limitations. In the end, the commune would succumb to the Constitutionalist military offensive.

In particular, although Zapata and Palafox proposed extending their legislation to the national level, their political strategy, in the essential moments of the revolution, showed the primacy of a regionalist perspective, the expression of a peasant-based movement. And that, in addition, the political and social immaturity of the young working class (as well as the harmful role of Constitutionalism, which co-opted working-class sectors) deprived the insurgent peasantry of the urban ally that could have powered a revolutionary struggle against the bourgeoisie for national political power. As we will see below, however, today’s EZLN does not uphold the most advanced and revolutionary principles of the original Zapatistas.

Neo-Zapatism of the 21st Century

There is no doubt that the Morelos Commune’s experience of self-government could not have been sustained for a single day without the expropriation of the landowners and the subsequent agrarian distribution. Moreover, the self-determination of the peoples and communities headed by the Liberation Army of the South could become real only through a profound economic transformation and through an attack—in this case, a regional one—on the old power of the ruling class. And precisely because it did not have a perspective to fight for power at the national level and transform the entire capitalist structure of the country, the Zapatista experiment in self-government could not find greater support or avoid defeat.

The actions of the Liberation Army of the South and the Morelos Commune, one of the most radical actors in the Mexican Revolution, should be contrasted with the experience and program of the EZLN. Undoubtedly, the latter’s Good Government Councils (created in 2003) and the actions of the Zapatista communities are part of a decades-long process of resistance against the bourgeois state and express the aspirations of indigenous peoples. Their defense against state repression—regardless of whether they govern neoliberally or “progressively”—is a matter of principle for revolutionaries.

Sixteen years since the experience of autonomy and self-management in the Zapatista communities began, however, it is necessary to draw conclusions. As announced on July 19, 2003, in a communiqué from the Clandestine Revolutionary Indigenous Committee-General Command of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation and by the Zapatista Rebel Autonomous Municipalities of Chiapas, “The EZLN decided to totally suspend any contact with the Mexican federal government and political parties, and the Zapatista communities ratified in making resistance their main form of struggle…. Zapatista and rebel indigenous peoples have prepared a series of changes that refer to their internal functioning and their relationship with national and international civil society.”

The EZLN thus broke with the Mexican regime and created its own institutions, searching for a path toward autonomy outside the capitalist system—a project aligned with Toni Negri’s idea of “communism here and now.” But this project left the prevailing relations of production untouched and did not confront the political actors that guarantee them—such as the union bureaucracy, NGOs, religious institutions, evangelical churches, etc. It likewise maintains the yoke of exploitation on the workers, leaving untouched the dynamic of looting and theft of indigenous land.

The case of coffee growers’ cooperatives is an example. Although production for self-consumption takes precedence, and the surplus is always small and barely enough to purchase some of the goods they do not produce—salt, soap, clothes, some food, medicines, lime—the coffee sector is dominated by multinationals like Starbucks and Nestlé, which impose market prices.[10] Zapatista cooperatives cannot escape this.

As Leandro Vergara-Camus points out,

It would be a mistake to argue that the Zapatista peasants are outside capitalist relations. As many studies have shown, the Zapatistas have been directly affected by the neoliberal restructuring of the countryside. In addition, the vast majority of them have had numerous experiences of wage labor in the ranches and cities of the region and even of temporary migration to other regions of Mexico. In the terms used by the new ruralists, the families that make up the EZLN have been multifunctional for several decades now.[11]

At the core of this discussion is that the EZLN command’s policy has dissociated the rightful claim to autonomy from the need for access to land and natural resources. This disassociation is found in the San Andrés Pact, which was adopted by the EZLN leadership as a true program.

The lesson of the experience of the Morelos Commune is that autonomy is real only as long as the communities have the right to land, a historical right taken away in a history of robbery and plunder—an accelerated accumulation of communal lands on which Mexican capitalism rests. The last great chapter of this history of plunder began with the reform to the 27th Article of the Mexican Constitution by former President Carlos Salinas de Gortari. This, along with the Agrarian Law of 1992, which promised “juridical security,” transformed the ejidos (communal lands) into private property with the certificates of parcel rights granted by the Registry of Agrarian Juridical Acts (RAJA). Thus, parcels of ejido lands can now be leased and sold.[12] In Chiapas this is aggravated by the state’s lack of infrastructure and means of production (irrigation embankments, troughs, wells, milking parlors, sawmills, tractors, vehicles and machinery), which economically suffocates the ejidatarios, who are forced to sell their parcels.

We Must Finish Zapata’s Work

Indigenous self-determination is unthinkable without the restitution of land. This requires a radical agrarian reform at the expense of the landowners—who own 41 percent[13] of Mexico’s 196 million hectares of land—and the multinational corporations. The latter are aided by the government through contracts to build megaprojects, such as the Mayan Train that President López Obrador has announced.

Similarly, the struggle for real autonomy leads to a confrontation with the state, which will hardly tolerate the undermining of large landownership. The EZLN leadership, however, has repeatedly stated that its strategy is not to abolish the capitalists’ power or to fight for a government of the exploited and oppressed. At this point it also differs from the experience of the Morelos Commune itself. Although it was limited to one region, state power was concentrated in that area, and it was based on the armed people and the expropriation of the landowners. The perspective of the EZLN’s leadership, in contrast, implies its coexistence with the power of the state and the construction of spaces (or “islands”) of autonomy, a strategy that evades the struggle to expropriate the means of production and free the whole of humanity from the chains of wage slavery.

A truly anti-capitalist perspective—considering that the EZLN claims to have such a perspective—must put forward the struggle for a government of workers, peasants, and poor indigenous people. An alternative power that breaks with imperialist domination and forges an alliance with the millions of immigrant workers and peasants in the United States—many of them coming from native communities—and that expropriates the capitalists and landowners, multinationals and agribusinesses. Without that, there is no way to meet the demands of the great majorities. Only a government of the workers and the people could, for example, provide the cheap credit and technical resources that poor peasants need, by expropriating the banks and industry. It could stop the dispossession, the environmental devastation, the handing over of water to large national and foreign companies, and guarantee the right to autonomy and access to land that is denied by the current political regime.

This undoubtedly implies seeking a revolutionary alliance with the working class, an alliance that will put the exploited and oppressed of the countryside and the city on their feet, with the aim of struggling for a new state, based on bodies of self-determination of the masses. The strategic objective of this alliance would therefore be communism, understood as a society of free associated producers. If in Zapata’s time this objective was unattainable given the limitations of Mexican capitalism in its infancy, today’s Mexico offers a real opportunity to realize it. The oppression and despoilment of Mexico’s rural masses is deepening, and a powerful proletariat has emerged in the countryside. The task is now to reclaim Zapata’s struggle and take it to the end.

Notes

- The 1857 Constitution originally disallowed reelection. Díaz pushed for reforms that slowly granted him the right to be elected as president uninterruptedly.

- Much of the information in this article was presented in Pablo Oprinari, ed., México en llamas: Interpretaciones marxistas de la Revolución Mexicana [Mexico ablaze: Marxist interpretations of the Mexican Revolution] (Mexico City: Armas de la Crítica, 2010), in particular the essays “Morelos 1915: To the Storming of Heavens,” by Jimena Vergara, and “The Paths of the Revolution,” by Pablo Oprinari. We have also drawn on Adolfo Gilly’s The Interrupted Revolution, a classic work in the Marxist historiography of the Mexican Revolution.

- Científicos in this case refers to a group of Mexican politicians close to Díaz who had great fortunes and landholdings. They sympathized with the positivism of Auguste Comte, arguing that they wanted to “advocate for the scientific direction of the government and the scientific development of the country” (hence the nickname of “scientists”). They became ministers of Díaz’s government eager to succeed him in the presidency, but their plans never came to fruition.

- Oprinari, “Paths of the Revolution,” 164.

- Felipe Ávila, Breve historia del zapatismo (Mexico City: Crítica, 2018), 194.

- Oprinari, “Paths of the Revolution,” 167.

- Ibid., 169.

- Ávila, Breve historia, 198.

- Oddly enough, the refraction of the Mexican Revolution in Chiapas was quite contradictory. It began in 1911, after the fall of Díaz and the appointment of two governors: one in Tuxtla and the other in San Cristóbal de las Casas, formerly the state capital. So it was that by 1912 Jacinto Pérez “Pajarito” (Birdie), a warlord from the town of Chamula, led a revolt against the Tuxtlecos (residents of Tuxtla). According to the Tzotzil oral tradition, although they do not have a word for revolution in their language, they define that process at the beginning of the 20th century as the period “when we ceased to be crushed” (“k’alal ich’ay mosoal”) (or “when we ceased to be waiters”). That was when they decided not to be baldíos (indebted peons) or waiters, as John Womack Jr. explains in Rebelión en Chiapas/Antología histórica (Rebellion in Chiapas/Historical anthology). By 1914, the so-called Chiapas finqueros (hacienda owners) of San Cristóbal and Tuxtla, liberals and conservatives respectively, united to expel Carranza’s troops. The Zinacantecos, Tzotziles, allied with the Ladino peasants, confronted them. Their motive was to put an end to debt bondage. The original Zapatismo, that of the Southern caudillo, had no influence in that state, although Rafael Cal y Mayor, the son of a large landowner, arrived there in 1916 and waged an unsuccessful campaign in which he had imprisoned some U.S. landowners and distributed the lands of a few haciendas.

- Sánchez Juárez and Gladys Karina, “Los pequeños cafeticultores de Chiapas: Organización y resistencia frente al mercado” [The small coffee growers of Chiapas: Organization and resistance to the market] (CITY: Universidad de Ciencias y Artes, Centro de Estudios Superiores de México y Centroamérica 2015), 200.

- Leandro Vergara-Camus, “Globalización, tierra, resistencia y autonomía: El EZLN y el MST” [Globalization, land, resistance and autonomy: The EZLN and the MST], Revista Mexicana de Sociología 73, no. 3 (July-September 2011), http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0188-25032011000300001.

- It is a process that takes place in a qualified general assembly in which, in the presence of a notary public and a representative of the Agrarian Attorney, 75 percent of the ejidatarios attend and agree with the change two-thirds of the participants. J. Carlos Morett-Sánchez and Cosío-Ruiz Celso, “Panorama de los ejidos y comunidades agrarias en México” [Overview of the ejidos and agrarian communities in Mexico], Revista Agricultura, Sociedad y Desarrollo 14, no. 1 (January-March 2017), http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1870-54722017000100125.

- Data from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), in “Rural Mexico of the 21st Century.”

Translation: Óscar Fernández