We have all seen the images: modern assembly lines in endless factories, where thousands of workers build small technological jewels. These images of Chinese workers chained to their little piece of the production line, repeating the same gestures over and over each day, are as ubiquitous as they are anonymous. Yet we know nothing of their lives, their hopes, or their dreams.

Some of these workers speak out — by writing down their words and troubles. A new generation of Chinese worker-poets is giving us the keys to understanding and getting closer to their reality, and thus to the reality of today’s world.

Members of the previous generation of Chinese poets, including the writer Bei Dao, were committed:

Let me tell you, world,

I — do — not — believe!

If a thousand challengers lie beneath your feet,

Count me as number thousand and one.1Bei Dao, “The Answer,” trans. Bonnie S. McDougall. Translator’s note: Bei Dao is the pen name of Zhao Zhenkai, nominated multiple times for the Nobel Prize in Literature. He was a member of the Red Guards as a young man, but later participated in the mass protest in Tiananmen Square in 1976 when Premier Zhou Enlai died. His poems were known to have inspired the later 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, and he was subsequently banned from China. He became a U.S. citizen in 2009.

Bei joined the Red Guards as a young man but later became disappointed in and disillusioned by the Cultural Revolution. Then he became a protester. He and other “obscure poets” used figures of speech, cryptic terms, and hermetic themes to avoid censorship but still criticize the regime. The new generation no longer hides. It knows the Chinese economic miracle needs to exploit millions of workers. And it has lost all hope.

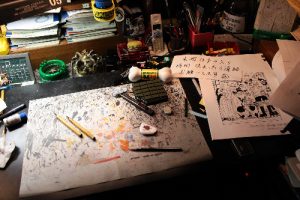

Their poems find their source in the vocabulary of work and industry. Cold as metal, sharp as a knife, they do not seek to depict a dreamlike universe or a means of escape. They take on the truth, cruel, sharp, and aggressive. Work is death. Seeing themselves as nothing more than replaceable cogs in the wheel of work, they dehumanize themselves. Used as an extension of the machine, they reify themselves in their poems by emphasizing the alienation of work on a production line.

A Man Falls to the Ground

Xu Lizhi leaves his family home in Guangdong Province in 2010 to work at the Shenzhen factory of Foxconn, China’s largest Taiwanese subcontracting multinational, exploiting more than 1.4 million workers. The company became well known in 2010 when media around the world reported a large wave of suicides among its workers. An important pillar of the international production chain, it represents the lightning progress of China’s export capacity.

Some time later, Xu leaves his job at Foxconn in the hope of finding something elsewhere that is more than screws, machines, and conveyor belts. His attempt to set up a small business with a friend fails. He dreams of becoming a bookseller but can’t find a job. So, on September 26, 2014, at the age of 24, with no money, he resigns himself to knocking on the door of the electronics giant once again. He is assigned to the same department, the same job, and the same position. On September 30, after that day’s shift, he heads for the shopping mall where his favorite bookstore is located, climbs to the roof above the 17th floor and throws himself into the void. His friends manage to save his poems and publish them.

Here are some of his poems:2Translator’s notes: These translations are taken from “The Poetry and Brief Life of a Foxconn Worker: Xu Lizhi (1990–2014),” at libcom.org.

A Screw Fell to the Ground

(Xu Lizhi — January 9, 2014)

A screw fell to the ground

In this dark night of overtime

Plunging vertically, lightly clinking

It won’t attract anyone’s attention

Just like last time

On a night like this

When someone plunged to the ground

I Swallowed a Moon Made of Iron

(Xu Lizhi — December 19, 2013)

I swallowed a moon made of iron

They refer to it as a nail

I swallowed this industrial sewage, these unemployment documents

Youth stooped at machines before their time

I swallowed the hustle and the destitution

Swallowed pedestrian bridges, life covered in rust

I can’t swallow anymore

All that I’ve swallowed is now gushing out of my throat

Unfurling on the land of my ancestors

Into a disgraceful poem

Foxconn has a military-style management structure. Employees must live in the group’s apartments, which are subject to very strict internal regulations (alcohol is prohibited, outsiders are prohibited, no sleeping over, etc.). In addition to the eight legal working hours per day, there is often compulsory and illegal overtime, which can be as long as four additional hours. Employees must attend the foreman’s “pitch” each morning, in which he sets the day’s (increasingly larger) objectives. These pitches often last more than half an hour of unpaid time. In 2014, under fire from media criticism over the number of suicides, the company slightly increased wages and set up a hotline for suicidal employees. But this is mainly used to scare “weak-minded” workers. Eventually, “anti-suicide” nets were installed in the windows of the warehouses, taking away from workers even the option to choose their own deaths. Freedom ends where profit begins.

Xu’s friend Zhou Qizao — a fellow worker at Foxconn — wrote this poem after learning of his friend’s suicide:

Upon Hearing the News of Xu Lizhi’s Suicide

(Zhou Qizao / October 1, 2014)

The loss of every life

Is the passing of another me

Another screw comes loose

Another migrant worker brother jumps

You die in place of me

And I keep writing in place of you

While I do so, screwing the screws tighter

Today is our nation’s sixty-fifth birthday

We wish the country joyous celebrations

A twenty-four-year-old you stands in the grey picture frame, smiling ever so slightly

Autumn winds and autumn rain

A white-haired father, holding the black urn with your ashes, stumbles home.3libcom.org.

Uprooting as a Point of Departure

To understand the lives of these workers, beyond the assembly lines and the alienation of work, we need to understand the situation of migrant workers from China’s interior. The academic Zhang Yulin first used the term migrant worker in China in 1984.4Translator’s note: Zhang Yulin, a researcher at the Institute of Sociology (part of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences) had been researching rural town and village enterprises (TVEs) in southern Jiangsu Province and wrote an academic article for the Journal of Sociological Research (Shehuixue Yanjiu Tongxun). TVE workers were typically surplus farmworkers. He found many were moving even farther away than the local towns and villages. In his article, he first referred to rural laborers who moved into cities for work as Nongmingong, or “migrant workers,” and the term has been widely used ever since. The growth of new industrial cities in eastern China stirred and attracted many peasants from the countryside in search of work, who were thought of as foreigners in their own country. A policy known as “Document 1,” issued by the Chinese government on January 1, 1984, allowed this large-scale migration of rural residents to the cities.

Although internal migration in China has always existed, it had been heavily regulated since 1956; workers needed permission from local authorities to seek work elsewhere. That made it impossible for 85 percent of Chinese people to migrate. The government needed such prohibitions to keep peasants in the countryside and maintain sufficient agricultural production. The purpose of such a restriction was to prevent residents from leaving their agricultural cooperatives to seek other ones across the country with better working conditions, which would have created a trend toward improving living conditions. The law served the same function as a wall around a labor camp: to prevent people from leaving.

Thirty years later, the development of industry and the development of a market economy in the country created a significant demand for labor in the cities. Consequently, the government removed travel restrictions to allow peasants to move to the cities and become workers. Today, an estimated 275 million Chinese people have moved from the countryside to the cities, creating many problems, such as a lack of housing, abandoned children, separated families, overcrowded cities, and so on.

In 2015, the laws on worker registration and temporary residence permits were abolished. While at least legally the term migrant worker became obsolete, the reality of the difficulties of internal migration has remained the same.

Poetry by migrant workers is called Labor Poetry. The use of “labor” implies the sale of labor power to a boss. It is the language of capitalism, and entered the country from Hong Kong to Guangdong in the 1980s. With the expansion of the capitalist economy in China, these terms have gradually replaced the socialist vocabulary related to labor. Poetry by workers emerged in the 1990s, when a small number of workers with some knowledge of literature began to write about their working conditions away from home — thus creating a new literary genre by those from the lowest strata of society.

Among them was Xie Xiangnan, who left Hunan to work in Zhejiang as a construction worker, line worker, dockworker, cutter at a paper factory, machine repairman, and so on. As his work experiences multiplied, he began to write about them. After sleeping for a week on a stone bench next to the Guangzhou railway station, he wrote a series of poems including “Guangzhou Train Station.” In it, he mentions two paintings that are in the textbooks used by Chinese schoolchildren: Eugène Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People and Alexander Gerasimov’s Lenin on the Rostrum. In Delacroix’s painting, the woman representing liberty walks with the insurgents in the smoke of the battlefield. This representation contrasts with the Gerasimov painting, in which Lenin stands above a crowd delivering his speech. Xie sees this as a metaphor for the Guangzhou station.

Guangzhou Tram Station

I remember the painting “Liberty Leading the People,”

a fairly safe picture, it appeared in our middle school history book

along with “Lenin on the Rostrum,” in which people gather below the stage

and raise up their weapons. I seem to remember hearing a sound leaping

from the page —

there was a huge crowd at the Guangzhou train station in March 1996 too

the bags piled on the square were like packages of explosives

and I almost imagined the digital clock towering overhead

was our beloved Lenin. Two foreign men in suits stood

beside a sign, an advertisement for American cigarette

and in march 1996, I was a kid from the country who didn’t smoke

pushed off the train by the flow of people, I was like a log

just pulled out of the forest. The earth and sky had already changed

a five-kuai meal could only fill up one corner of my stomach

and people kept bumping into me — brushing past

with the same face, like uncontrollable revolutionary fever

an old man in a armband had caught a woman and was going to fine her

while girls loitered in the countryard and laid out their wares in the night

fruit and motor scooters, newsstands and scalpers flashed past my eyes

how many people were there? Or maybe it was just me: waiting

for “Beloved Lenin” to open a breach in time

to take the unfamiliar clothing — and put it on like a pro.5In Iron Moon: An Anthology of Chinese Worker Poetry, ed. Xiaoyu Qin, trans. Eleanor Goodman (Buffalo, NY: White Pine Press, 2016).

The revolutionary language has disappeared, and the world has changed. The masses are no longer those insurgents but hurried workers. There is no longer a revolutionary leader but a huge digital clock that guides the people.

The World Is Ours

These migrant poets are part of the Chinese tradition of itinerant intellectuals living on odd jobs and living at the bottom of society. Unlike most modern writers, they have to do a job they hate, far from the places they love, just to survive. In their writings, they are not interested in big philosophical or political issues; they speak in simple language of their daily experiences and paint pictures of a life few Western readers know.

It would be wrong to think that these workers, because they talk about their daily lives, are uninterested in the world around them. Indeed, many are well aware that their daily lives are a sad reality that does not belong to them. Exploitation at work, the body destroyed by machines and a hellish pace, and miserable wages are all themes that can be understood by workers throughout the world, from the Amazon warehouses in France to Chile’s copper mines. This is the case of the poet Guo Jinniu who, in an interview, explains his relationship to writing:

Poetry is the only thing on this earth that doesn’t reject me. And I don’t reject poetry. I want to write about people, and about life. … Poetry isn’t independent. It’s closely connected to life. Maybe it’s me writing, and maybe it isn’t me. Maybe what I write represents my group of workers. Or maybe it represents the situation of millions of migrant workers.6Workers Poetry Project, interview with Guo Jinniu, in Iron Moon, documentary film (2016).

His texts, as he is well aware, are not the result of literary genius or of his ability to perceive the world in a more subtle or refined way than his contemporaries. If Guo Jinniu himself indeed writes them, his texts belong to workers all over the world. They do not speak of his life but of the life of his class. He continues,

For example, I wrote a poem about a river being polluted. Maybe the river isn’t just mine, maybe it belongs to everyone. No matter what. You’re a migrant worker. Are you the only one thinking about these things? Maybe a lot of other people are thinking about it. Maybe one day you go home and it’s polluted, but it’s not only your home. Pollution is a national issue. It’s not something ordinary people can solve. We might destroy it in a year. But to clean up the river might take a hundred years. Or maybe it can never be brought back. What I’ve seen, what I’ve noticed, I have to tell others about.

That’s why these poems are so political, even though they describe only everyday life. Indeed, by tackling themes such as pollution, nature, and thoughts on the protection of ecosystems, they raise the question of responsibilities. Who does a river really belong to? The conglomerate that owns it? The industrialists who pollute it? The inhabitants who depend on it to survive?

Luzu Village’s Past

(Guo Jinniu)

A slab of concrete plus another slab, isn’t it still the earth?

The seeds know.

Industrial pollutants drain into a river, but isn’t still a river?

The fish know.

Made in China.7In Xiaoyu, Iron Moon.

The question of roots, of where one grew up, is an important dimension for these poets. Always uprooted, often alone, sometimes destroyed, they use poetry to reconnect with their native land and their history. Guo continues,

Maybe poets naturally have drifting somewhere in their bones. Up to today, I’m still drifting. I have a steady job, but I’m still drifting in it. If I had to choose again, I’d still leave home when I was young. I’d still choose to go somewhere else. But even when you’re just a kite, the string is still attached to where you grew up. And that shapeless string is there no matter how far you float.

These poets are well aware that what they write is not unique to them. It is about all their migrant brothers and sisters who experience the same things. Perhaps they are not even talking about Shanghai or Shenzhen, but about the contemporary world as a whole. To think of China as an exception in the globalized capitalist world would be a mistake. Profit, the search for ever-greater profits, can only tend to increase the exploitation across the globe. Chinese migrant workers, moving from assembly lines to lines of poetry, tell us much more about the world we live in than many contemporary Western intellectuals. The latter have been particularly well known for their “quarantine journals” full of verbiage whose mediocrity is equaled only by the emptiness of the words they write.

The Chinese worker-poets, in keeping with the history of workers’ literature and the tradition of Chinese poetry, have achieved a literary syncretism of rare quality. It is regrettable that these texts are not better known.

First published in French on July 20 in RP Dimanche.

Translation by Scott Cooper

Notes

| ↑1 | Bei Dao, “The Answer,” trans. Bonnie S. McDougall. Translator’s note: Bei Dao is the pen name of Zhao Zhenkai, nominated multiple times for the Nobel Prize in Literature. He was a member of the Red Guards as a young man, but later participated in the mass protest in Tiananmen Square in 1976 when Premier Zhou Enlai died. His poems were known to have inspired the later 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, and he was subsequently banned from China. He became a U.S. citizen in 2009. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Translator’s notes: These translations are taken from “The Poetry and Brief Life of a Foxconn Worker: Xu Lizhi (1990–2014),” at libcom.org. |

| ↑3 | libcom.org. |

| ↑4 | Translator’s note: Zhang Yulin, a researcher at the Institute of Sociology (part of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences) had been researching rural town and village enterprises (TVEs) in southern Jiangsu Province and wrote an academic article for the Journal of Sociological Research (Shehuixue Yanjiu Tongxun). TVE workers were typically surplus farmworkers. He found many were moving even farther away than the local towns and villages. In his article, he first referred to rural laborers who moved into cities for work as Nongmingong, or “migrant workers,” and the term has been widely used ever since. |

| ↑5 | In Iron Moon: An Anthology of Chinese Worker Poetry, ed. Xiaoyu Qin, trans. Eleanor Goodman (Buffalo, NY: White Pine Press, 2016). |

| ↑6 | Workers Poetry Project, interview with Guo Jinniu, in Iron Moon, documentary film (2016). |

| ↑7 | In Xiaoyu, Iron Moon. |