In November 2023, Amazon workers signed a petition demanding “an immediate end to the company’s complicity in the genocide being carried out against Palestinians in Gaza.” The workers denounced Amazon’s provision of technology and artificial intelligence services to the state of Israel. This was not the first instance of Amazon worker actions in solidarity with Palestinians: Two years earlier, in October 2021, more than four hundred workers at Amazon and Google staged protests against Project Nimbus, a $1.2 billion contract the multinational companies signed with the Israeli government to provide services to the occupying army. Nimbus was intended to create a “digital ecosystem” for “increased surveillance and illegal data collection on Palestinians,” in addition to facilitating the “expansion of Israel’s illegal settlements on Palestinian land,” the workers declared.

This is the starting point of Josefina L. Martínez’s new book, Amazon desde dentro: el secreto está en la explotación (Amazon from the Inside: Exploitation is the Secret to Its Success), published in March 2024 in Spain.

In the introduction, the author stresses that “at a time when the barbarism and hypocrisy of the world’s most powerful states takes on ever-more brutal forms, these small steps are very significant. Indications of new militancy, which, if extended, would open the possibility of an alternative to the current conditions of capitalist dystopia.”

Martinez has been writing about the Amazon strikes and other workers’ struggles in the Spanish magazine Revista Contexto for several years. For this book, she interviewed workers and activists involved in organizing campaigns at Amazon in Spain and the UK and others working within major U.S. logistics companies like UPS. The book takes up several major debates, including the “Amazonification” of capitalism, the spread of global logistics chains, and the reconfiguration of the working class in the 21st century, in dialogue with authors such as Cedric Durand, Aaron Benanav, Kim Moody, Paula Varela, Gastón Gutierrez, and Esteban Mercatante, among others.

The prologue to the book was written by Pastora Filigrana, a labor lawyer and anti-racist activist of Roma origin. Filigrana notes that “capital not only wants employees to work for lower wages; it also wants them to work longer hours. To this end, technology is put at the service of the control and discipline of working people.” She cites as an example the geolocators used by companies like Uber to monitor delivery drivers and the use of time-measuring devices at Amazon. However, she points out that when “people are required to work longer for less, there is a constant risk of social and union conflicts.” Martinez’s Amazon from the Inside, says Filigrana, “collects the first-person voices of those who are facing the challenges of building a trade union movement that is not satisfied with pursuing simply improvements in labor conditions or wages, but rather seeks to question the economic and social ordering of the world from inside the belly of the beast.” To delve deeper into these issues, we interviewed Josefina Martinez.

***

You’ve subtitled the book: “Exploitation is the Secret to (Amazon’s) Success.” That is quite a statement against the neoliberal discourse of meritocracy, which presents the success of these billionaires as the result of the initiative of a few individuals. Is that the idea?

Yes, in the book I take up what is called the myth of the Silicon Valley garage. According to this ultra-neoliberal ideology, it is entrepreneurship that paves the way for a thousand flowers to bloom in the capitalist market. In particular, technology companies like Amazon, Google, or X very much promote the idea that digital technology allows for a democratization of the rules of the game for companies and users. Their success is the supposed award for those “innovators” with a “daring spirit” who go beyond the conventional practices. In Argentina, Milei is a big advocate of these types of ideas.

The reality is that technology is a sector with an enormous concentration of capital. To make it clearer: 25 years ago, the largest capitalist companies in the world in terms of market capitalization were oil and energy companies. Now the most lucrative companies are Apple, Microsoft, Google and Amazon. These companies benefited tremendously from the pandemic. So while millions of people around the world were suffering, they pocketed billions. In the case of Amazon, its profits have been phenomenal. Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, and Bill Gates are among the five richest men in the world.

There is another narrative that needs to be dismantled: The idea that these companies are succeeding because of artificial intelligence, innovations in logistics, or robotics. Obviously this gives them enormous comparative advantages. But their profits cannot be explained if we do not look at the precarity of their global workforce. Amazon is one of biggest employers in the world, directly employing more than 1.5 million workers (and that’s not counting the hundreds of thousands of outsourced delivery workers, or falsely-labeled self-employed workers).

In the book you mention another common vision around these types of platform companies and the technologies they’ve introduced: the idea of a “surveillance capitalism” from which it would be impossible to escape.

Yes, Shoshanna Zuboff is one author who puts forward this idea: changes in digital technology are leading us to a new social order, in which Internet and social media users are transformed into an entity whose life is stolen by digital companies through multiple mechanisms. Where “governance” would now go through a digital control of bodies. These theses are questioned by several Marxist authors, because they unilateralize to infinity an aspect of reality. They completely erase the structural dynamics of capitalism, its contradictions, the exploitation of labor, the role of capitalist states and, above all, the class struggle. It is as if there were an omnipotent and vigilant power, a kind of digital dystopia.

It is true that Amazon and other companies are increasingly using technologies for surveillance and control. In the case of Amazon, it has been reported that Amazon Rekognition — the company’s facial recognition system — is used for border control in the United States. And internally, they use control mechanisms to intensify the pace of work in their warehouses. But if we only see that, it can lead us to resignation, as if there is no escape. And the truth is that this is not the case: Amazon does not work without workers, the same as the rest of the technology companies, from warehouse workers, to call center attendants, to programmers.

In the book you examine the wide variety of industries the company has ventured into: what exactly is Amazon today?

It is one of the largest companies in global logistics. But it is much more. It is one of the most important online sales platforms on the planet and controls about half of the data storage infrastructure in the cloud (where many other companies store their data).

Amazon takes advantage of the internationalization of supply chains, something that allowed capitalists to relocate production and lower production costs over the last decades — what author Corsino Vela calls a “dispersed Fordism,” with production and supply chains spread across various countries. It is part of a revolution in logistics in recent years, which is based on a network of warehouses, containers, ships, trains, planes and trucks. That physical network is connected by a digital network: barcodes, satellite tracking techniques, Big Data. It is what is known as “smart” logistics. Amazon has about 1100 logistics warehouses in the world, half in the U.S., about 350 in Asia, 250 in Europe and a few dozen in the rest of the world. Researcher Kim Moody points out that Amazon is a leader in what Marx called the “annihilation of space by time.” The key is to move goods very quickly over thousands of kilometers, entering warehouses through one door and leaving through another.

But that’s not the end of it. By controlling the online retail platform, Amazon has additional advantages over its competitors. It captures, in real time, data from hundreds of thousands of transactions and can quickly see which products are selling the most, or which products are being searched for at that moment in each location. Many times, when it detects a niche market, Amazon can offer its own products at significant discounts to compete. All this makes for enormous profitability.

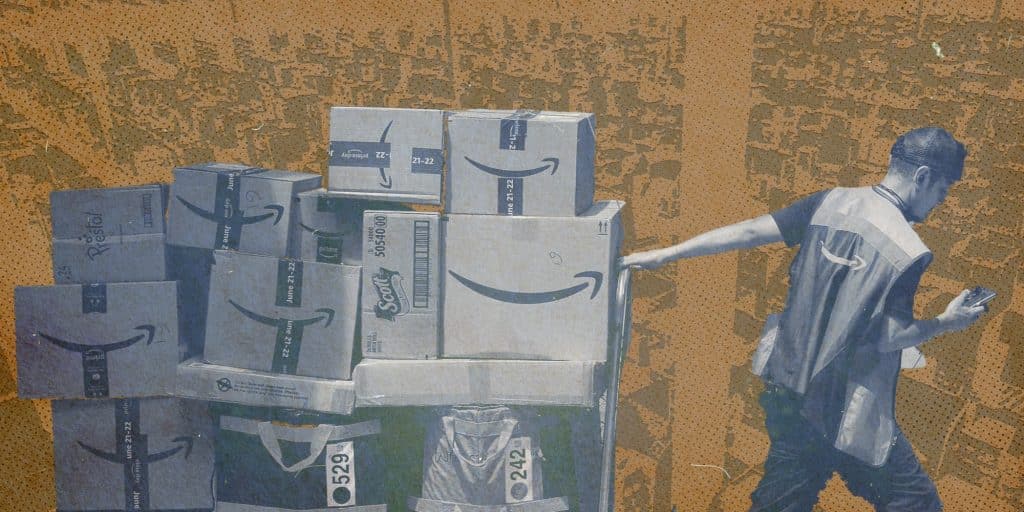

Let’s put the magnifying glass on Amazon’s hidden secret: what happens inside the warehouses and in the delivery?

Amazon’s warehouses are huge facilities, many of them highly automatized, employing several thousand workers and operating around the clock. Amazon has tried several different methods for the so-called “last mile,” all of which make use of highly precarious workers.

All the tasks performed by the workers in the logistics centers, as Moody emphasizes in several papers, are part of the sphere of production, even if no other material change is made to the goods other than their transfer. And that is where the legalized theft that Marx called surplus value takes place. The objective is to increase this theft of labor time as much as possible, and for that Amazon uses mechanisms to control every movement of its workers, to intensify the labor process.

Workers at the MAD4 warehouse in Madrid have to use an individual device that sends them the location of the products inside the huge warehouse. Once the order goes out, the clock starts ticking. If the scanner is not flagged in time, the system counts it as a failure. If a lot of failures add up by the end of the day, that worker will be written up and it can be grounds for dismissal. In other warehouses, there are devices with voice commands for each worker, which are also quite stressful forms of control.

Some researchers define this as an “algocratic” form of control (that is, algorithm plus autocracy). The combination of this high degree of control alongside automation, robotics, and AI transforms the whole way of working in warehouses and the entire logistics network.

If we go back to Marx, he analyzed that, in the hands of capital, technical-scientific development, instead of creating more free time for workers, is transformed into surplus labor. Instead of freeing workers from the burden of labor, capital binds them with heavier chains and uses technical means to discipline and control them.

Amazon is an example of the technification of control. In its robotized and digitized warehouses there is a 19th century exploitation, but imposed with 21st century techniques. When Amazon workers say “We are not robots” they are pointing to the dehumanization of labor by capital and the steady degradation of their working conditions. They are also warning that there will be resistance.

Several authors point out that logistics workers can, if they go on strike, affect what is, in effect, the central nervous system of capitalism — the supply chains and the movements of goods. How do you address this in the book?

There is no doubt that logistics workers play an important role in today’s capitalism. Razmig Keucheyan compares it to the miners of the early 20th century, who had the ability to paralyze coal production and distribution, which in turn affected production in many other sectors of the economy. Logistics workers have a strategic position in logistics nodes. As Kim Moody points out, huge logistics hubs have developed near major cities that could become choke points if workers can organize and coordinate with each other. These logistics centers house thousands and thousands of workers in the same space or in nearby industrial parks. Logistics warehouse workers, truck drivers, dock workers, railway workers and workers in nearby offices could constitute a very strong working force if they unite, for example, for a strike, a highway blockade, or a mobilization against the bosses. They are part of a new working class that is very precarious, but potentially very dangerous for the capitalists.

But in the book you also point out that they are sectors of the logistics workforce that face many difficulties in organizing, right?

Exactly, Amazon and other logistics companies make use of all possible mechanisms to divide and fragment the labor force. One is the massive hiring of casual workers, thus generating a huge division in the workforce between permanent and part-time workers. When there are strike threats, Amazon brings in thousands of casuals in the weeks leading up to the strike, effectively using these workers as strikebreakers. Another mechanism is to divert orders to another nearby warehouse, within the same country or even in a neighboring country. In Germany, Amazon workers have repeatedly complained that the company diverted orders to warehouses located in Poland in order to break strikes.

Researcher Nantina Vgontzas studied the processes of organizing workers in warehouses in Germany by the Ver.di union. Her conclusion is that Ver.di did not manage to overcome these difficulties very well, as it did not innovate or seek new forms of organization that would create greater unity among the workforce, and restricted itself to a traditional trade union model of seeking wage bargaining with management. This is important to keep in mind. There are various unionization campaigns taking place around the world within Amazon’s workforce. In some countries, they try to prevent it at all costs, as in the United States and the United Kingdom. But in others, where it already exists, as in Spain or France, they try to co-opt the union leadership, so that the status quo of precariousness is maintained.

The conclusion that can be drawn is that, although Amazon workers (and logistics workers generally) occupy a key strategic position, this does not automatically mean greater power vis-a-vis the company. In order to make use of this advantage, it is necessary, first of all, to go beyond the methods of “traditional unionism” or the old union bureaucracies, to recover combative forms of struggle, to unite the demands of permanent and temporary workers, native-born and migrant workers, warehouse workers and transport workers, men and women workers, to be able to articulate a powerful force that truly challenge the company.

Two years ago, workers at Amazon’s distribution center in Staten Island, New York, won the first unionized shop at Amazon in the U.S. How has this example affected organizing efforts elsewhere in the world? To what extent is the “Generation U” phenomenon seen in the U.S. becoming internationalized?

There is no doubt that the struggle of the Amazon Staten Island workers has had a global impact. In many countries it was seen as a David versus Goliath struggle. The union’s success was won through a powerful campaign by activists, who faced all kinds of maneuvers, intimidation and union-busting tactics by the company: smear campaigns against union organizers, investigations into their personal and family lives, spreading fake news about unions, to holding intimidation meetings with workers to scare into them into rejecting the union.

But the majority of workers were not deterred by these tactics. They managed to build strong bonds of solidarity across gender and racial barriers that the capitalists often use to divide the workforce. In that sense it is very auspicious.

There is a lot of talk about Generation U: the youngest members of the working class, who are losing their fear, gaining confidence, and building momentum to organize unions. They are strongly influenced by movements like Black Lives Matter or the women’s movement. I think that’s something very interesting. For the book I interviewed Luigi Morris, a UPS worker in New York, who talked about the process of organizing among this sector of workers.

I think there are similarities in other countries. In the United Kingdom, two years ago, a wave of strikes began in which young people and migrants, alongside more traditional sectors, nurses and teachers participated. There are parallels between the fights in the United States and Europe, it seems to me. We have also seen it in the struggles in France — a more combative, new trade union militancy.

In the book you take up again the debate on the reconfiguration of the working class at a global level, in a counterpoint with several authors… Goodbye to work or welcome working class?

It seemed necessary to me to take up these questions again, in the face of so much ideology around the supposed “end of work.”

In the book I return to some questions taken up by Aaron Benanav, Esteban Mercatante, Paula Varela, and Gastón Gutiérrez; I recommend reading their articles. To summarize just a couple of ideas: although there are deindustrialization processes around the world, they are very uneven. Furthermore, in many regions the number of people reliant on wage labor has grown enormously. In recent years, these sectors have begun to be the protagonists of important struggles. I argue instead that we should focus more on the transformations of the labor force, its feminization, the impact of migration, and the processes of fragmentation in some sectors, but also on the new working class concentrations around big cities, etc.

What I am most interested in emphasizing is that all the divisions and fragmentations of the working class are not something given, nor the product of the “changing times,” which would make it no longer possible to carry out massive and militant struggles. Rather, they are a consequence of the offensive of capital against labor in the neoliberal period and the normalization of the defeats by the union bureaucracies. There is a crucial point: the role of these bureaucracies and the necessity of confronting them. It is striking that this is not very problematized in labor studies.

In several countries we can notice a return of the willingness to strike: from the Generation U to the autoworkers strike in the United States, along with major strikes in the United Kingdom and France in recent years. The most important thing now would be how to achieve coordination between different sectors, so that the bureaucracies cannot divide the struggles: How to unify all the sectors of the working class, and the working class with other oppressed sectors, the social movements, etc. so that they do not end in defeat or become coopted by capitalist parties like the Democratic Party in the U.S.? That is the challenge it seems to me.

In closing, the epilogue of the book leaves us with a question: What if we expropriate Amazon? There are those who might think that this is a complete utopia, considering the power of this company and its extension around the globe.

If Amazon can employ, on a global level, such an immense quantity of technical and scientific resources and create new, smart logistics, why can’t these resources be at the service of social needs, of the majority of the population? Imagine if, during the pandemic, this enormous logistical network had been reconfigured to deliver vaccines and medical supplies to the many regions of the planet where they were in short supply….

In the epilogue I want to impart the idea that all these resources, created by the accumulation of knowledge and human labor, can be put at the service of the whole of society, and not the profits of a few. Jeff Bezos makes trips to space and we all pay the cost. It is time to put an end to this irrationality, to reorganize the whole of production, circulation, and reproduction on the basis of truly democratic principles. The planning of the economy by the workers themselves, a socialism from below, could count on all the technological advances of the 21st century.

Of course, Amazon has a global presence and it would be difficult to expropriate it all at the same time. But I am sure that if the workers in the United States or in Germany succeeded in putting Amazon under workers’ control, a wave of enormous enthusiasm would spread throughout the world.

Translation by Robert Belano