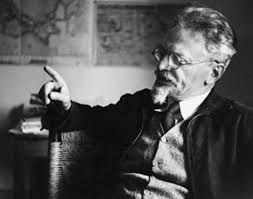

You could be forgiven for knowing little about Leon Trotsky — the man, his accomplishments, and his contributions to the world revolutionary movement — or even for having a distorted sense of these things. Depictions of Trotsky in popular culture typically avoid his politics or present them in “monotones” that belie the tremendous depths he plumbed as a revolutionary activist and theorist. In the 2002 biopic Frida, Salma Hayek’s Frida Kahlo has an affair with Trotsky during his exile in Mexico, but his politics are largely missing from the film. Trotsky is missing altogether from Warren Beatty’s celebrated film Reds (1981), even though he was a central leader of the Russian Revolution. The 2009 comedy The Trotsky depicts a teenager named Leon Bronstein (Trotsky’s birth name was Lev Davidovich Bronstein) who believes he is the reincarnation of Trotsky and attempts to unionize his family’s clothing factory and then the students at school. It’s funny, but despite the occasional line that viewers very familiar with the real Trotsky might “recognize,” it hardly presents a worthy picture of the man’s political ideas.

Why is Trotsky so little known or distorted in the broadly defined revolutionary movement, especially here in the United States? Unlike Lenin, Luxemburg, Che Guevara, Mao, and many other revolutionary heroes, Trotsky and his legacy make him a target of a historically powerful component of the workers’ movement, one that needed to revise revolutionary history to secure its power in the Soviet Union after Lenin’s death. He was demonized while alive, and continues to be in death. The objective continues to be to keep his critique beneath the surface, to keep the masses unfamiliar with the man whose ideas most clearly represent the legacy of revolutionary Marxism — traceable back to the Russian Revolution and even earlier.

C. L. R. James, the great Black revolutionary Marxist, explained in “Trotsky’s Place in History” (under his pen name J. R. Johnson) why those who worked to overturn the Russian Revolution from within, just like leading ruling-class figures, were so concerned with Trotsky.

Stalin knew that as long as Trotsky lived and could write and speak, the Soviet bureaucracy was in mortal danger. In a conversation just before war broke out, Hitler and the French ambassador discussed the perils of plunging Europe into conflict and agreed that the winner of the second great war might be Trotsky. Winston Churchill hated him with a personal malevolence which seemed to overstep the bounds of reason. These men knew his stature, the power of what he stood for, and were never lulled by the smallness of his forces.

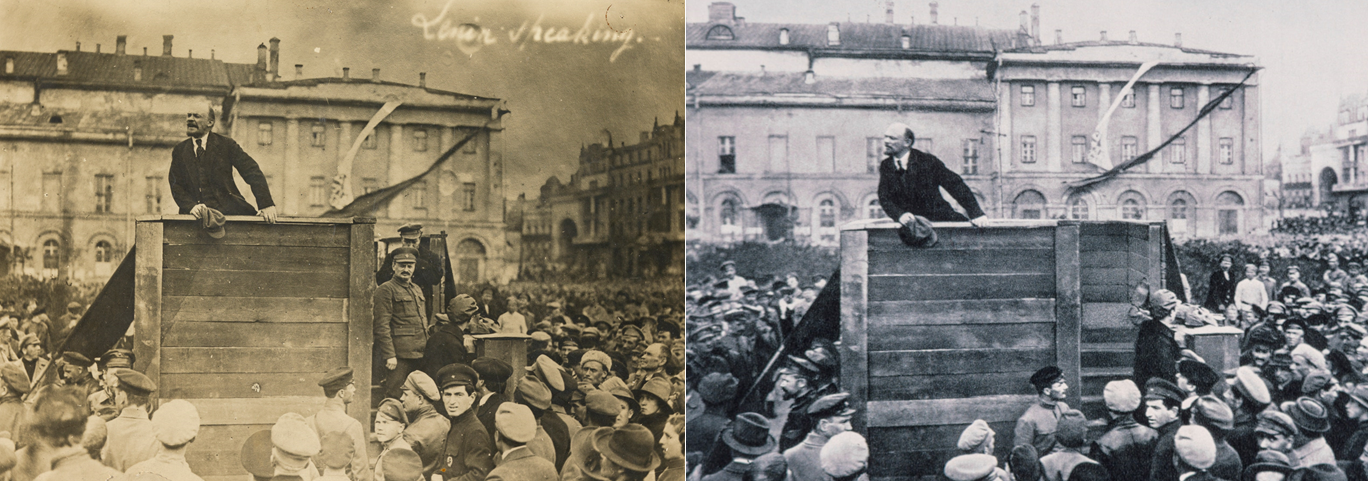

Trotsky was even airbrushed out of Russian revolutionary history — as you can see in the two photos below.1For the full, fascinating story of this perverse project, see David King, The Commissar Vanishes: The Falsification of Photographs and Art in Stalin’s Russia (New York: Metropolitan Books, 1997).

As George Kennan, historian, early Cold War-era U.S. diplomat, and one of the architects of the strategy of “containment” for the Soviet Union, once wrote, “Trotsky, and all that Trotsky represented, was Stalin’s fear.”2George F. Kennan, “Russian and the West under Lenin and Stalin,” Naval War College Review 14, no. 8 (1961): 6.

It wasn’t Trotsky as a rival for leadership, however, that kept Stalin up at night. It was that his revolutionary ideas were the antithesis of Stalinism.

Today, Trotsky is not widely known among radicalizing young people or by the emerging vanguard of revolutionary-minded people who have been leading the struggle in the streets. This speaks volumes about the persistence of Stalin’s historical “airbrushing.” To those who are familiar with this history, the Trotsky they think they know is often a caricature of the man and his ideas. The latter are often grossly misinterpreted. Many have fully internalized a false narrative about his role in the Russian Revolution, one that Stalin and his minions promoted for decades.

Nevertheless, his revolutionary ideas live on. Many of those ideas are guiding the uprisings taking place today.

You may be interested in Remembering Trotsky’s Contributions

The story of Trotsky and his ideas is a rich and exciting one. It’s a story of revolutionary activism. It’s a dynamic tale of vital political strategizing through discussions taking place under the cover of darkness and with assassins lurking everywhere. The scenery is different, but it is an adventure story every bit as compelling as Che in the Bolivian mountains.

Trotsky Emerges as a Revolutionary Leader

Space does not allow a full explication of Trotsky’s history. A brief political biography must suffice.

Lev Davidovich Bronstein was born in a small Ukrainian village in 1879. He was sent off to cosmopolitan Odessa at age eight for school. In 1896, he moved to a town along the Black Sea coast, joined the narodniks (a populist group of agrarian socialists), and was won to Marxism. He abandoned schooling and never looked back, helping organize the South Russian Workers’ Union and agitating among local industrial workers and students.

Trotsky was among more than 200 members of the union arrested in 1898. He spent two years in prison awaiting trial, met other jailed revolutionaries, and read Lenin’s book The Development of Capitalism in Russia. When the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party (RSDLP) held its first congress while he was in jail, Trotsky declared for the party. Sentenced to exile in Siberia, he took sides in party discussions and supported the Iskra (the Spark) group, which published a newspaper in London with that name and that supported building a disciplined revolutionary combat party to overthrow the Russian monarchy.

Escaping from Siberia, Trotsky made his way to London, where he worked closely with the Iskra editors — including Lenin — and became one of the main writers. But writing wasn’t enough. Trotsky was a man of action. In early 1905, with Saint Petersburg in upheaval, he secretly returned to Russia to join the fight. Full-blown revolution broke out later that year, and Trotsky became the leader of the Saint Petersburg Soviet of Workers’ Delegates. The revolution was crushed, and Trotsky was again arrested and exiled to Siberia.

He escaped again, this time en route.

He returned to London, and then to Vienna. In 1908, he joined the editorial staff of Pravda (Truth), produced by exiles and smuggled into Russia. Over the next years, until 1917, he actively participated in the debates and discussions around the revolution Russia needed and would ultimately experience. He spent time in Paris during World War I, was deported to Spain for his anti-war activities, and then to the United States, arriving on Christmas Day 1916. During his little-known three months in New York City, he made speeches, met leading U.S. socialists of the time, and wrote extensively for the Russian-language socialist newspaper Novy Mir (New World) and the Yiddish-language daily Der Forverts (the Jewish Daily Forward).

A revolution in February 1917 overthrew the Russian czar. Trotsky left New York for Russia, but the British navy intercepted the ship he was on and imprisoned him in Nova Scotia. That didn’t stop Trotsky’s political work. In his autobiography, My Life, he described his discussions with worker and sailor inmates — mostly German prisoners of war — as “like one continuous mass-meeting.”

I told the prisoners about the Russian revolution, about Liebknecht,3Liebknecht was a revolutionary Marxist leader in Germany at the time. about Lenin, and about the causes of the collapse of the old International, and the intervention of the United States in the war. Besides these speeches, we had constant group discussions. Our friendship grew warmer every day.4Trotsky, My Life, chap. 23, “In a Concentration Camp” (1930).

Trotsky’s work among these proletarians enraged the German officers who were also inmates. They demanded that the British camp commander shut him up. Trotsky was forbidden from making any more “public” speeches in the jail, but 530 prisoners protested — signing a petition demanding that his “rights” be reinstated. Meanwhile, back in Russia, workers’ and peasants’ soviets (councils) established after the February revolution began to demand Trotsky’s release, and the British government relented in late April 2017.

Back in Russia again, Trotsky was at the center of the opposition to the Provisional Government of Alexander Kerensky, which was not following through to complete the overthrow of the Russian bourgeoisie. He became president of the soviet in Petrograd (Saint Petersburg’s new name). He was a main leader of the insurrection that threw Kerensky out — what we today call the October Revolution. Even Stalin acknowledged his role, although what he wrote in 1918 was later expunged from his collected works.

All practical work in connection with the organization of the uprising was done under the immediate direction of Comrade Trotsky, the President of the Petrograd Soviet. It can be stated with certainty that the Party is indebted primarily and principally to Comrade Trotsky for the rapid going over of the garrison to the side of the Soviet and the efficient manner in which the work of the Military Revolutionary Committee was organized.5Joseph Stalin, “The October Revolution,” Pravda, no. 241, November 6, 1918. See Note A regarding the omission of this text.

Trotsky was tough and uncompromising when it came to revolutionary politics. Look up “badass” in a dictionary and you’ll usually find those two descriptors.

From October 1917 to Expulsion from the Soviet Union

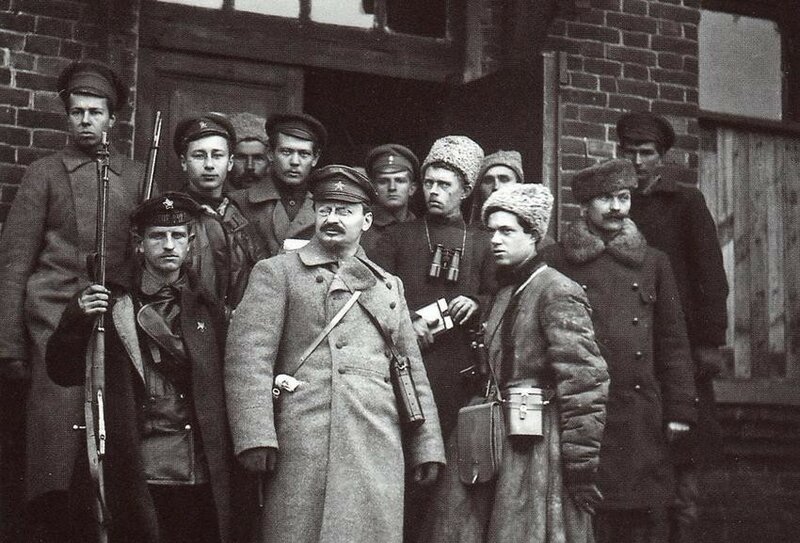

After the October Revolution — which Lenin and Trotsky both led — Trotsky served in a number of capacities as a member of the Bolshevik Central Committee. He organized the Red Army and, as People’s Commissar of Military and Naval Affairs of the Soviet Union, successfully led the country’s defense in the Civil War (1917–23) against pro-capitalist Russian forces backed by foreign governments. This included defeating attacks by various capitalist governments on 16 fronts in 1919.

Meanwhile, Lenin’s health was deteriorating, and Stalin was consolidating a group around him to challenge Trotsky and take control of the Bolshevik Party and the entire USSR. Trotsky and others fought these efforts to undermine and ultimately subvert the revolution. The full history is worth knowing, but it cannot be recounted here. A few key points must suffice.

Stalin wanted to win power for himself, but Trotsky’s focus was on preserving the gains of the Russian Revolution. Stalin developed a “theory” antithetical to revolution to justify the growing bureaucratization of the Soviet Union. The theory of building “socialism in one country” negated the view that Russia — seen as the weakest link in the capitalist chain — could somehow go it alone to advance to communism, without the help of revolutions in far more developed capitalists states such as Germany. This idea, which Trotsky spent the rest of his life fighting, is the origin of the Stalinist regime’s later policies of class collaboration, the pact with Hitler, the betrayal of Spain’s working class in the country’s civil war, “peaceful coexistence,” and so on — because everything was subordinated to what served the interests of preserving the pretend “socialism” in “one country,” the Soviet Union, and the bureaucratic caste that Stalin created, which sat atop the workers’ state.

When Lenin died in 1924, Stalin suppressed a document known as Lenin’s “Testament,” in which Lenin argued for removing Stalin as the party’s general secretary. Although Lenin had mildly criticized Trotsky, it was clear that Lenin saw him as the leader who would move the Soviet Union forward.

Over the next few years, Stalin employed every machination to marginalize Trotsky and his criticisms of Stalin’s leadership direction. Anti-Stalin sentiment first coalesced around a “United Opposition,” which included some other Bolshevik leaders, but that alliance was broken. By the time of the party conference in October 1926, the Stalin wing had organized the crowd to disrupt Trotsky when he spoke. The next year, Stalin unleashed his secret police on the opposition. Rank-and-file Bolsheviks who opposed him began to be arrested and expelled from the party.

In October 1927, Trotsky was expelled from the party’s Central Committee. Stalin was beginning the process of eradicating the “Old Bolsheviks” who had led the revolution — a process that would culminate on August 21, 1940, in Mexico. By the end of that year, expulsions of rank-and-file oppositionists had reached a fever pitch. Early the next year, opposition leaders were sent into internal exile. Trotsky’s own exile took him first to Alma Ata, Kazakhstan, for a year.

The Beginnings of Close Association with Americans

None of this stopped Trotsky from waging his battle against Stalinism within the party. James P. Cannon, a founding leader of the American Communist Party (CP) who was already having his own doubts about the direction Stalin was taking the world communist movement, traveled to Moscow for the Sixth Congress of the Communist International in 1928. He was put on the program commission.

You may be interested in Why Trotskyism

But that turned out to be a bad mistake. … It cost Stalin more than one headache … Because Trotsky, exiled in Alma Ata, expelled from the Russian party and the Communist International, was appealing to the Congress. You see, Trotsky didn’t just get up and walk away from the party. He came right back after his expulsion, at the first opportunity … not only with a document appealing his case, but with a tremendous theoretical contribution in the form of a criticism of the draft program of Bukharin and Stalin. … Through some slip-up in the apparatus in Moscow, which was supposed to be bureaucratically airtight, this document of Trotsky came into the translating room of the Comintern. It fell into the hopper, where they had a dozen or more translators and stenographers with nothing else to do. They picked up Trotsky’s document, translated it and distributed it to the heads of the delegations and the members of the program commission. So, lo and behold, it was laid in my lap, translated into English! Maurice Spector, a delegate from the Canadian Party, and in somewhat the same frame of mind as myself, was also on the program commission and he got a copy. We let the caucus meetings and the Congress sessions go to the devil while we read and studied this document. Then I knew what I had to do, and so did he. Our doubts had been resolved. It was as clear as daylight that Marxist truth was on the side of Trotsky. We made a compact there and then — Spector and I — that we would come back home and begin a struggle under the banner of Trotskyism.6James P. Cannon, The History of American Trotskyism (New York: Pioneer Publishers, 1944), 49.

The Trotsky document was an exposé of Stalin’s theory of “socialism in one country.” Trotsky analyzed its anti-Marxism, how it would inevitably lead to the degeneration of the communist movement and to an anti-revolutionary adaptation to nationalism and reformism.

Cannon’s discovery was the beginning of Trotsky’s close association with what would become American Trotskyism, and he didn’t even know it. The next year, Trotsky was expelled from the Soviet Union altogether and sent to Turkey.

Meanwhile, Cannon returned home, where he “proceeded immediately” with his “determination to recruit a faction for Trotsky” in the American CP — not a simple thing to do. Thanks to Stalin, “the whole party was regimented against” Trotsky, and by then “the party was no longer one of those democratic organizations where you can raise a question and get a fail discussion. To declare for Trotsky and the Russian Opposition meant to subject yourself to the accusation of being expelled forthwith without any discussion.”

Under such circumstances the task was to recruit a new faction in secret before the inevitable explosion came, with the certain prospect that this faction, no matter how big or small it might be, would suffer expulsion and have to fight against the Stalinists, against the whole world, to create a new movement.

For the very beginning I had not the slightest doubt about the magnitude of the task.7Ibid., 51, emphasis added.

Trotsky toiled in exile, with no knowledge that he had won over some important leaders in the world communist movement. Cannon recruited to Trotsky’s position one by one — first his companion Rose Karsner, and then Martin Abern and Max Shachtman, members of the CP National Committee. Then the small group moved on, facing tremendous obstacles.

We had one copy of Trotsky’s document, but didn’t have any way of duplicating it; we didn’t have a stenographer; we didn’t have a typewriter; we didn’t have a mimeograph machine; and we didn’t have any money. The only way we could operate was to get hold of carefully selected individuals, arouse enough interest, and then persuade them to come to the house and read the document. A long and toilsome process. We got a few people together and they helped us spread the gospel to wider circles.8Ibid., 52.

Over time, they would win a group of communists to the perspective of continuity with Marxism and the Russian Revolution, to standing firm against the increasing bureaucratization in Russia and the ultimate defanging of the world revolutionary movement to which Stalin and his “theories” would lead. They were expelled from the Communist Party, went on to found the Communist League of America (CLA) as a public faction of the CP to win over its ranks, published a newspaper (the Militant), and eventually determined — through discussions with Trotsky — that a new revolutionary party needed to be built in the United States along with a new revolutionary international. The Fourth International would replace the bankrupt, Stalinized, counterrevolutionary Comintern.

Meanwhile, Trotsky’s exile took him to France in 1933, and later to Norway, always under constant surveillance and with Stalin’s agents trying to undermine his extensive political activity and threatening his life. He focused on helping organize the opposition from afar while writing prolifically on every important political issue of the day both in the Soviet Union and worldwide — including the brewing world war. Then the Stalin government in 1936 announced the discovery of a “Trotskyist-Zinovievist” plot in Russia, and the era of the great Stalinist show trials began — with death sentences and executions wiping out even more of the “Old Bolsheviks.” As 1936 closed, Trotsky was expelled from Norway.

Throughout the ordeal, Trotsky held firm to his revolutionary ideals. And with a group of Americans now part of the International Left Opposition, he began to collaborate closely with Cannon and the others. He engaged actively, through his writings and meetings with Americans who visited him in his various exile locations, in the CLA’s debates on important political questions facing the U.S. working class. He explained and endorsed the group’s theses on building a labor party in the country. He regularly wrote for the Militant. When a Trotskyist leadership waged one of the most important labor struggles in American history — the 1934 Teamsters strike in Minneapolis — he was in regular contact with the CLA’s national office discussing not only issues of day-to-day strategy but also the larger question of how to move the U.S. trade union movement to a more revolutionary perspective. He was central to how the American Trotskyists accomplished what Cannon described this way:

In Minneapolis we saw the native militancy of the workers fused with a politically conscious leadership. Minneapolis showed how great can be the role of such leadership. It gave great promise for the party founded on correct political principles and fused and united with the mass of American workers. In that combination one can see the power that will conquer the whole world.9Cannon, ibid., 167.

The lessons of Minneapolis — not only about flying pickets to confront the cops at every turn, or about how to make sure strikers and their families got their daily needs for food met so on, but also about how to organize a movement to go beyond its immediate objectives — are lessons that come from Leon Trotsky and American Trotskyism.

Onward to Greater Collaboration

On January 9, 1937, Trotsky and his wife, Natalia, arrived in Mexico, which had agreed to grant him political asylum when they had to leave Norway. They lived first with the painters Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in their home in the Coyoacán neighborhood of Mexico City, and two years later they moved to their own home a few blocks away.

Trotskyists from the United States played a critical role for Trotsky in Mexico. Americans traveled to Mexico to guard his household. They were his secretaries, transcribing and translating his writings. Leaders and even some rank-and-file members of what became the Workers Party when the CLA and the American Workers Party fused visited Coyoacán regularly for extensive discussions on issues facing the party and the U.S. working class as a whole. As Jimena Vergara recently put it in Left Voice, “Trotsky gave fundamental importance to thinking, with great imagination and strategic intransigence, about ways to build a revolutionary organization in the United States, and he did so in political struggle with Cannon and the American Trotskyist leadership.”

You may be interested in The Trotskys Betrayed

A strategist to the end, always thinking of how to advance the revolutionary struggle, Trotsky continually engaged with American Trotskyists. As Vergara writes, “These initiatives, elaborated in five years of intense intervention … had the objective of making the revolutionary program become embodied in the vanguard, something which is impossible without bold tactics, political struggle, and clear intransigence in defending the revolutionary program.”

He worked closely to develop the best ways to intervene in the unions and how to proletarianize the party itself. He provided a deeper understanding of how to build coalitions and the importance of principled united fronts. Without Trotsky, for instance, it is doubtful that the Socialist Workers Party would have built one of the biggest anti-fascist mobilizations during the runup to World War II — when 20,000 New Yorkers filled Madison Square Garden in New York City for a pro-Nazi rally, and the Trotskyists organized a counterprotest that drew 50,000.

One of Trotsky’s most significant contributions was to help elaborate for his American co-thinkers how to reorient to the Black struggle in the United States. His argument had two components: first, Black workers would play a central role in the coming American revolution; second, working-class unity could be achieved across racial lines only if white workers recognized the legitimacy of oppressed minorities’ struggles and gave unconditional support to their right to self-leadership and self-determination. He admonished the American Trotskyists that they must be in the front ranks of the fight for Black rights and the fight against racism among white proletarians.

It is very possible that the Negroes also through the self-determination will proceed to the proletarian dictatorship in a couple of gigantic strides, ahead of the great bloc of white workers. They will then furnish the vanguard. I am absolutely sure that they will in any case fight better than the white workers. That, however, can happen only provided the Communist party carries on an uncompromising merciless struggle not against the supposed national prepossessions of the Negroes but against the colossal prejudices of the white workers and gives it no concession whatever.10Trotsky, “The Negro Question in America” (1933).

There were many other lessons from Trotsky. Those he taught about the united front are part of why the SWP was the force behind the largest anti-war mobilizations during the Vietnam War — organized on a clear anti-imperialist line without succumbing to the ultraleft sectarianism of some small groups that did not understand what Trotsky had taught: that we needed to get the working class to see the war as opposed to its interests. When we marched in the streets during those days, it was impossible not to think that the spirit of Trotsky was marching beside us.

Trotsky’s “intense intervention” continues to pay dividends today.

The founding document of the Fourth International, known as the Transitional Program, is imbued with that spirit — not only of the man but also of the ideas and lessons learned over decades of revolutionary struggle. It is about “the mobilization of the masses around transitional demands to prepare the conquest of power.” Everyone marching in the streets today, everyone wondering what to do about the upcoming elections, everyone who wants to move Black Lives Matter forward, everyone who thinks we need to get organized for revolution, ought to devour that book. It is as compelling a guide to what we, as revolutionaries, need to do to win as it was when it was first published in 1938.

As the Transitional Program proclaims,

If capitalism is incapable of satisfying the demands inevitably arising from the calamities generated by itself, then let it perish. “Realizability” or “unrealizability” is in the given instance a question of the relationship of forces, which can be decided only by the struggle. By means of this struggle, no matter what immediate practical successes may be, the workers will best come to understand the necessity of liquidating capitalist slavery.

Trotsky’s Enduring Legacy

Leon Trotsky the man was the embodiment of revolutionary continuity. His forebears in the Russian revolutionary movement had worked with Karl Marx. He was a comrade of Lenin; they worked side by side for years. When he was expelled by Stalin, he brought those connections with him to the rest of his life’s work.

You may be interested in Leon Trotsky’s Legacy and the Present

More important, though, is that Trotsky’s ideas represent continuity today. They are dangerous ideas. That’s why you may not know them — because the enemies of those ideas continue to work to keep them suppressed. The pretend revolutionaries who would have us vote for Joe Biden recognize that Trotsky’s ideas, which are really the ideas of true revolutionary Marxism, challenge their reformism. The rulers know that Trotsky’s ideas are a powerful guide to action, and action with one purpose — their demise.

Perhaps precisely because his ideas are so dangerous, more and more young people around the world are starting to be drawn to Trotsky, uncovering this hidden history and these suppressed ideas. The powerful plunderers of the world ought to be trembling, because as this new generation discovers Trotsky, it will learn that he literally wrote the book, the guide to revolutionary action, on overthrowing their racist, oppressive system.

Next time you’re out marching for justice and against oppression, just remember that Trotsky is marching with you. When your union is on strike, remember that Trotsky is walking that picket line with you. When you sit with comrades to figure out next steps, remember Trotsky has some powerful ideas for you to consider. He even made clear what the ultimate objective of our revolution must be. The day before his assassination, he wrote, “Life is beautiful. Let the future generations cleanse it of all evil, oppression, and violence and enjoy it to the full.”

Notes

| ↑1 | For the full, fascinating story of this perverse project, see David King, The Commissar Vanishes: The Falsification of Photographs and Art in Stalin’s Russia (New York: Metropolitan Books, 1997). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | George F. Kennan, “Russian and the West under Lenin and Stalin,” Naval War College Review 14, no. 8 (1961): 6. |

| ↑3 | Liebknecht was a revolutionary Marxist leader in Germany at the time. |

| ↑4 | Trotsky, My Life, chap. 23, “In a Concentration Camp” (1930). |

| ↑5 | Joseph Stalin, “The October Revolution,” Pravda, no. 241, November 6, 1918. See Note A regarding the omission of this text. |

| ↑6 | James P. Cannon, The History of American Trotskyism (New York: Pioneer Publishers, 1944), 49. |

| ↑7 | Ibid., 51, emphasis added. |

| ↑8 | Ibid., 52. |

| ↑9 | Cannon, ibid., 167. |

| ↑10 | Trotsky, “The Negro Question in America” (1933). |