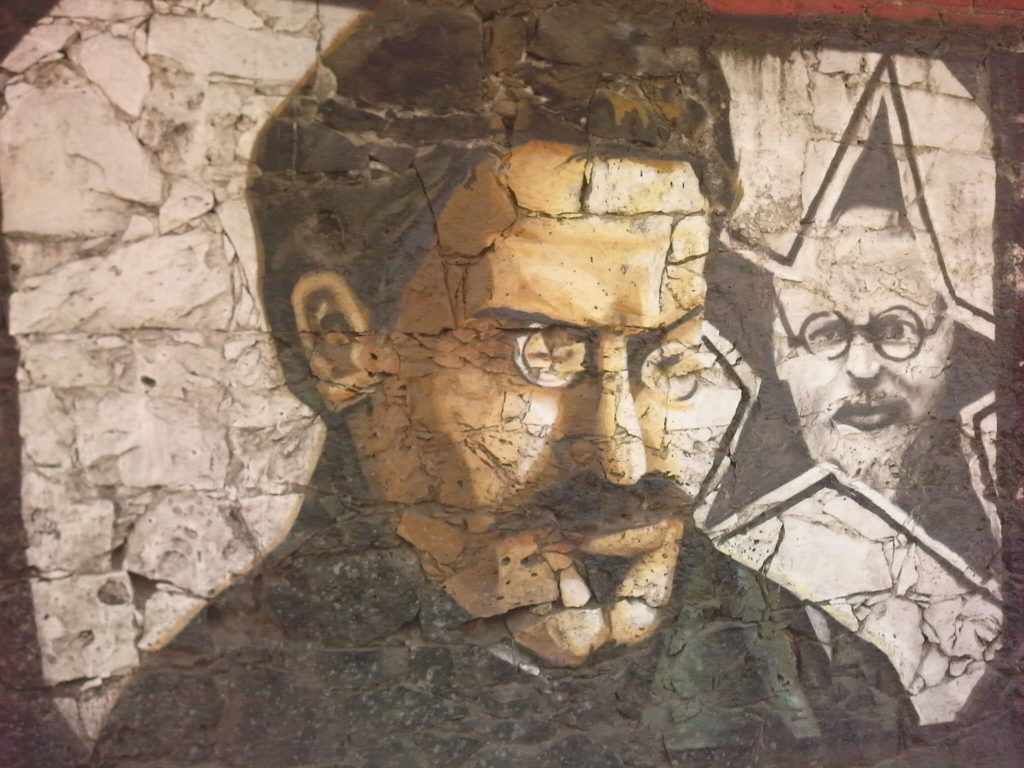

This year marks the 80th anniversary of the assassination of Leon Trotsky. At home in Mexico, where he was exiled, a hit man sent by Stalin struck the blow that ended his life. It was not an irrational act but a cold-blooded political calculation by the Soviet Union’s ruling bureaucracy, which believed that Trotsky was a tremendous danger given the discontent that a world war could generate within the working class and among communists internationally.

Just as Stalin embodied the counterrevolutionary bureaucracy that seized power through blood and fire in history’s first workers’ state, Trotsky embodied the Marxist alternative to Stalinism.

At the beginning of the struggle against Stalin, Trotsky already had an extensive revolutionary résumé. His biographer Isaac Deutscher wrote, “So copious and splendid was Trotsky’s career that any part or fraction of it might have sufficed to fill the life of an outstanding historic personality.”1Isaac Deutscher, The Prophet Outcast — Trotsky: 1929 1940 (London: Oxford University Press, 1963), 512. And Deutscher was right: by 1917, he had already gone through two exiles, after escaping from the prisons and deportation camps of czarism. He had been president of the Petrograd Soviet in the 1905 Revolution, an agitator against the imperialist war, and one of the most brilliant Marxist theorists of his time. Twelve years before the October Revolution, he foresaw with great precision the revolution’s dynamic, proclaiming the “heresy” that the working class, not the bourgeoisie, would lead the peasantry and defeat czarism. He also anticipated that the working class would not stop at the boundary of private property but would begin taking measures aimed at building socialism. Trotsky’s first formulation of his theory of “permanent revolution,” a concept with a long revolutionary tradition that was part of the debates of Marxists of the time, had a clearly distinctive meaning.

If Lev Davidovich Bronstein (his real name) had died in the early 1920s, around the time of Lenin’s death, he would have been remembered as one of the two great leaders of the October Revolution, as the founder of the Red Army, as its leader in the Civil War, and as the mentor of the Third International, which, before its bureaucratization, in its first four congresses, constituted the top rung achieved in constructing a general staff of the international working class.

As Deutscher also pointed out, the ideas Trotsky put forward and the work he did as head of the Left Opposition in Russia from 1923 to 1929 comprise the sum and substance of the most significant and dramatic chapter in the annals of Bolshevism and Communism. He was the protagonist of the greatest controversy to take place within the 20th-century communist movement, as a proponent of industrialization and of the planned economy and, finally, as the spokesman of all those within the Bolshevik Party who resisted the rise of Stalinism. “Even if he had not survived beyond the year 1927,” his biographer wrote, “he would have left behind a legacy of ideas which could not be destroyed or condemned to lasting oblivion, the legacy for the sake of which many of his followers faced the firing squad with his name on their lips.”2Deutscher, The Prophet Outcast, 513.

In that dispute, from 1924 onward, the bureaucracy held the reactionary conception that it was possible to build “socialism in one country,” which was the basis for abandoning a consistently internationalist policy. Against the Stalinists who argued that in colonial and semicolonial countries the working class had to trail behind some sector of the bourgeoisie, Trotsky argued that under certain circumstances the working class in these states could come to power even earlier than in an advanced capitalist country. But at the same time, he argued, the full construction of a socialist society requires the triumph of the revolution in the main capitalist countries, since capitalism is a world system and triumphing over it requires the conquest by the working class of its most developed productive forces. This is nothing more and nothing less than the basis of proletarian internationalism, which had already put forward by Marx and Engels in The Communist Manifesto.

In the course of the struggle against Stalinism, after the defeat of the Left Opposition, some Trotsky’s comrades repudiated their ideas and capitulated, which did not save them from being killed by Stalin during the great purges years later. But there were many others who bravely resisted all sorts of pressure, to the end. Stalin’s prisons were transformed into the school of a new revolutionary generation that could be reduced only by applying the “final solution” — a widespread massacre of oppositionists, carried out in the same years as the infamous Moscow Trials, during which the State Political Directorate (GPU), Stalin’s political police, wrested false confessions out of those accused.

Already in exile, first in Turkey and then persecuted on what he called in his autobiography “the planet without a visa,”3Leon Trotsky, My Life, chap. 45, “The Planet without a Visa” (1930). Trotsky devoted himself to organizing the Left Opposition on an international scale. After Stalinism refused to organize the workers’ united front to confront Nazism, and after Hitler’s rise to power provoked no reaction in the ranks of the Communist International, he considered the phase of fighting for a reform of the Soviet Communist Party and the Communist International exhausted, and raised the need to build new revolutionary parties and a new Fourth International. He also argued that a political revolution was needed in the USSR to sweep the bureaucracy from power and restore the rule of workers’ councils and Soviet democracy — a revolution that would at the same time both bring an end to the despotic regime and maintain the property relations that had emerged from the October Revolution, on which the bureaucracy had to rely while gradually undermining its foundations.

Five years later, in 1938, with Trotsky already in his Mexican exile, the Fourth International was founded at a clandestine meeting on the outskirts of Paris, on the basis of a document we know as “The Transitional Program.” It encapsulated the programmatic and strategic lessons of the previous Internationals and the struggle against Stalinism in the quest to prepare the revolutionary vanguard to face the advent of World War II and the counterrevolutionary and revolutionary circumstances that would result from its outbreak. With the old guard of the October Revolution having been eliminated, Trotsky considered his role in maintaining the continuity of revolutionary Marxism to be far more important than the role he had played at the helm of the Red Army or in the seizure of power. His very existence was a nuisance that Stalin could not tolerate, and that was why he was assassinated.

Trotsky’s death meant the disappearance from the scene of a huge revolutionary personality, perhaps the most prolific Marxist theorist and strategist of the 20th century. He was the one who knew how to stand firm when others faltered, the one who even in the most adverse situation was convinced that a communist future was the only progressive destiny to which humanity could aspire. As he stated in his “Testament”:

For forty-three years of my conscious life I have remained a revolutionist; for forty-two of them I have fought under the banner of Marxism. If I had to begin all over again I would of course try to avoid this or that mistake, but the main course of my life would remain unchanged. I shall die a proletarian revolutionist, a Marxist, a dialectical materialist, and consequently, an irreconcilable atheist. My faith in the communist future of mankind is no less ardent, indeed it is firmer today, than it was in the days of my youth.

Natasha has just come up to the window from the courtyard and opened it wider so that the air may enter more freely into my room. I can see the bright green strip of grass beneath the wall, the clear blue sky above the wall, sunlight everywhere. Life is beautiful. Let the future generations cleanse it of all evil, oppression, and violence, and enjoy it to the full.

Despite all the time that has passed since his death, Trotsky’s name still evokes the perspective of social revolution.

On the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution of October 1917, Russian President Vladimir Putin’s government sponsored a miniseries plagued by historical distortions and slander about Trotsky’s life. When in 2019 Netflix made it available internationally, it generated immediate and widespread repudiation, as expressed in the number of signatories to the a declaration entitled “Netflix and the Russian Government Join Forces to Spread Lies about Trotsky.” Estebán Volkov, Trotsky’s grandson, and the Center for Study, Research, and Publication of Leon Trotsky first promoted the declaration. Many internationally renowned intellectuals joined this initiative, including Fredric Jameson, Nancy Fraser, Slavoj Žižek, Robert Brenner, Mike Davis, Michael Löwy, Michel Husson, Stathis Kouvelakis, Franck Gaudichaud, Eric Toussaint, Suzi Weissman, Kevin B. Anderson, Alexander V. Reznik, Paul Le Blanc, and others, along with a multitude of leaders and members of the anti-Stalinist Left in different countries.

Trotsky’s unrelenting struggle against the Stalinist bureaucracy also makes him a nuisance to liberals, who work overtime to identify communism with bureaucratic totalitarianism. To the contrary, though, the perspective for which the founder of the Fourth International was assassinated is that of a democracy a thousand times superior to the most extensive of bourgeois democracies. We saw its antecedents in the Paris Commune and the Russian soviets, in which working people could deliberate each day and decide on the economic and political destiny of their society, planning production democratically. Without this, it is impossible to overcome the structural contradictions and irrationalities of the capitalist system. This workers’ democracy is an inevitable step in moving from what Marx called the “realm of necessity” to the “realm of freedom” — that is, to a fully communist society.4Translator’s note: Karl Marx, Capital, vol. 3, chap. 48, “The Trinity Formula” (1883).

Trotsky and the Current Crisis

The 80th anniversary of Trotsky’s death comes in a world shocked by the consequences of the coronavirus pandemic. To a certain extent, this event was foreseeable — after all, depending on the criteria we use, this is the third or fourth episode of unusual virus transmission from animals to humans so far in the 21st century, the result of a combination of factors such as deforestation, intensive animal husbandry in food production, new consumption habits, and means of potentially rapid propagation. The World Health Organization itself had warned of the possibility of such a pandemic. But no steps were taken to prepare health systems.

At the same time, what has become evident are the dire consequences of the policies internationally by which health budgets have been slashed and the health sector has been privatized and turned into an oligopoly. Adjustments in the health sector intensified in particular after the 2008 economic crisis, as many countries shifted their spending to debt payments to save the banks.

Meanwhile, the pharmaceutical industry that manages the world’s most extensive laboratories have directed production toward areas more profitable than infectious diseases, at the same time that state-sponsored research in that field remains grossly underfunded. The corporations that make up “Big Pharma” in the United States, for example, have abandoned research and development of new antibiotics and antivirals to focus on more profitable drugs, such as addictive painkillers. Now, with the pandemic underway, there is brutal competition among nations and laboratories to determine who gets the business of a Covid-19 vaccine.

The pandemic triggered not only a health crisis but also an economic and social crisis — one that will have lasting consequences. Uncertainty and the lack of health resources has led various governments to implement, to varying degrees, social isolation measures that have put a brake on a global economy that was already stagnant and facing predictions of a forthcoming crisis. The result has been millions of newly unemployed and newly impoverished people. Over a three-month period, the U.S. economy fell by the equivalent of what happened between 1929 and 1932, during the Great Depression. Although many countries have allocated billions of dollars to rescuing capitalists (for the most part) and some direct resources to aid in the subsistence of the general population, lifting the quarantines will not just return everything to the way they were before. No one knows for sure how long some sectors of the economy will continue to be affected. A joint study by two United Nations organizations, the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) and the International Labour Organization (ILO), predicts that, as a result of the pandemic, GDP in Latin America and the Caribbean will contract by at least 5.3 percent by the end of 2020, the equivalent of losing 31 million full-time jobs in the second quarter. This will entail an increase in poverty, bringing the proportion of the region’s population living in poverty to 34.7 percent, or 214.7 million people — with extreme poverty affecting 13 percent, or 83.4 million people.5ECLAC/ILO, “Work in Times of Pandemic: The Challenges of the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19),” in Employment Situation in Latin America and the Caribbean no. 22, May 2020. The specter of default is also spreading internationally both to nations and companies. Total public and private debt worldwide has reached $253 billion, three times the size of global GDP. A study by investment bank J.P. Morgan predicts that in the near future one in five countries will not pay their debts.

Meanwhile, as all this unfolds, some of the world’s richest people have increased their fortunes. Among them are Amazon boss Jeff Bezos, billionaire Elon Musk, Microsoft’s Steven Ballmer, real estate mogul John Albert Sobrato, Zoom founder Eric Yuan, Joshua Harris of Apollo Global Management, and Mediacom’s Rocco Commisso.

This situation allows us to predict that there lies ahead an increase in tensions between nations and between classes. The United States and China continue their escalation of a new type of “cold war” — a peculiar one that in the previous “cold war” the United States had practically zero economic exchange with the Soviet Union, but many U.S. corporations are in China or have direct interests in China. It is not so bold to predict that the rising trend of popular rebellions before the pandemic in so many countries will pick up again, as is already being illustrated with the mobilizations in the United States after the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police.

Before the pandemic, the wave of rebellion had touched many different regions of the planet. There were uprisings in North Africa, both in Algeria and Sudan. There were uprisings in the Middle East and the Persian Gulf region, including in Lebanon, Iraq, and Iran. In Asia, there was Hong Kong. In Latin America, we saw uprisings in Ecuador, Chile, Colombia, and the resistance to the coup in Bolivia. And before that, there were Puerto Rico, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. In Europe, people rose up in Catalonia and France more than once, first with the “Yellow Vests” and then with the strike against French president Emmanuel Macron’s pension reform. Together, these actions expressed the growing discontent of millions of people with an increasingly unequal world.

The entire neoliberal cycle has involved a huge transfer of resources from the world of labor to capital. The Lehman Brothers crisis in 20086Translator’s note: Lehman Brothers, then the fourth-largest U.S. bank investment bank and heavily involved in subprime mortgages, filed for bankruptcy in September 2008 — which is considered to have been one of the major precipitants of the global crisis that then erupted. shattered the neoliberal capitalist equilibrium; since then a new period of international economic growth has been unachievable — even though the crisis was prevented from reaching the levels of the 1930s by countries’ taking on monumental amounts of debt. International economic stagnation has been at the root of the escalating “wars” and trade disputes between the United States, China, and the European Union, of which Brexit is also part. The parties of what Tariq Ali called “the extreme center”7A term Ali coined to define the transformation of parties such as conservative and social-democratic or labor parties in two-party regimes into two sides of the same neoliberal political bloc. Translator’s note: Tariq Ali is a British-Pakistani writer and political activist (formerly a Trotskyist) who is a member of the editorial committee of New Left Review. See The Extreme Centre: A Warning (London: Verso, 2015). tended to enter into crises, become marginalized, or find themselves with politically polarizing leaderships, as has happened with Trump in the Republican Party or with the movement in 2016 and 2020 around the Bernie Sanders presidential candidacy, thwarted in both cases within the Democratic Party. With the magnitude of the current crisis, the tendency can only be for greater social and political polarization. Even the potential relocation of some areas of production within the imperialist countries themselves will involve attacks on wages and working conditions in those countries, with the bosses wanting to impose “Chinese” standards. There will be resistance.

At the same time, we have been witnessing a new and massive eruption of the women’s movement in various countries. This cannot be separated from the growing female character of the workforce and the greater suffering capitalism imposes on working women. Unpaid domestic work, which falls mainly on women, is a permanent feature of capitalism. The full emancipation of women can take place only with the elimination of the capitalist system.

The present also shines a brighter light than ever before on the seriousness of the damage caused by the irrational use of nature’s resources. Even with a slight pause in carbon dioxide emissions because of the pandemic, we are experiencing a genuine ecological crisis from which there is no way out within the framework of the capitalist system. In the next historical period, if we fail to succeed in ending capitalism, capitalism could end all of us.

The political phenomena that had been brewing before the pandemic will take on a new meaning. Obviously, the postpandemic world will not be the same as it was before. What it will become cannot be predetermined; it will be decided in the arena of class struggle. If we are to influence the course of this crisis, the lessons and method expressed by Trotsky in “The Transitional Program” are indispensable. As he wrote,

It is necessary to help the masses in the process of the daily struggle to find the bridge between present demand and the socialist program of the revolution. This bridge should include a system of transitional demands, stemming from today’s conditions and from today’s consciousness of wide layers of the working class and unalterably leading to one final conclusion: the conquest of power by the proletariat.

Demands such as the nationalization under workers’ control of factories that shut down or initiate layoffs, the nationalization of banking and foreign trade, the reduction of work hours without cuts in wages so work hours can be distributed among the employed and unemployed, the sliding scale of wages (with automatic increases for inflation) are on today’s agenda in many countries. Of course, the capitalists and their spokespersons will always say that meeting such demands is impossible. It is worth remembering what Trotsky wrote in “The Transitional Program” in the face of the same kinds of argument during another crisis of historical magnitude such as the one we face today:

The question is one of guarding the proletariat from decay, demoralization and ruin. The question is one of life or death of the only creative and progressive class, and by that token of the future of mankind. If capitalism is incapable of satisfying the demands inevitably arising from the calamities generated by itself, then let it perish. “Realizability” or “unrealizability” is in the given instance a question of the relationship of forces, which can be decided only by the struggle. By means of this struggle, no matter what immediate practical successes may be, the workers will best come to understand the necessity of liquidating capitalist slavery.

Will the current crisis spark a process that goes beyond rebellion to open revolution? Although any historical prognosis is always conditional, the magnitude of the current crisis suggests that we will likely see new revolutionary situations that jeopardize governments and regimes. Will some of them lead to revolutionary victories of the working class? It is impossible to say, because the development of revolutionary situations depends on a particular combination of objective and subjective elements. But we are convinced that if this does not happen, the future for the working class will be bleak.

That said, we have no reason for historical pessimism. There is no god who has decreed that the exploited will not again challenge the power of capital in this 21st century. We cannot allow the years we have spent without revolutionary processes led by the working class make us lose historical perspective. We must never forget that, in the 20th century, workers and peasants managed to break the power of the bourgeois state in several countries. But those revolutions either became bureaucratized, as in the Soviet Union, or were implanted, almost from the very beginning, with single-party regimes and ruling bureaucracies that prevented the masses from exercising real power. By not bringing the revolution to the centers of the imperialist system, they allowed capitalism’s counterattack, including capitalist restoration in the former Soviet Union, China, and other countries. This history, coupled with more recent events, make it essential that we update the strategic debates over the theory of “permanent revolution.”

First, there is the stumbling role of the national bourgeoisies in the oppressed countries, which have been unable to put an end to dependency and backwardness. This is clear in Latin America, where the same bourgeois nationalist movements that emerged with anti-imperialist rhetoric took direct responsibility for applying the neoliberal policies of the 1990s — Peronism in Argentina with Menem;8Translator’s note: Carlos Menem was president of Argentina from 1989 to 1999. He identified ideologically with Peronism, the enduring Argentine political movement based on Juan Perón, who served as Argentina’s president from 1946 to 1955, was then overthrown in a military coup, and was again elected president in 1973 when open elections were again held. He died the next year, his widow Isabel took his place, and the military overthrew her government in 1976. Peronism is a corporatist-populist ideology aimed at enlisting the working class as part of a tripartite “coalition,” along with the state and the capitalists, to mediate tensions and ultimately ensure the continuation of the capitalist system. the PRI in Mexico with Salinas de Gortari and Zedillo;9Translator’s note: The Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI, Institutional Revolutionary Party) was founded in Mexico in 1929, and it held absolute power until 2000 under various names. Its primary ideology of corporatism was buttressed by alternating co-optation and violent repression of the working class, and it engaged in widespread electoral fraud over decades to maintain itself in office. Carlos Salinas de Gortari was the PRI president of Mexico from 1988 to 1994 and was involved in creating the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Ernesto Zedillo was the PRI’s last president during the uninterrupted 71-year period, serving from 1994 to 2000. the Revolutionary Nationalist Movement in Bolivia;10Translator’s note: Founded in 1941, the Movimiento Nacionalista Revolucionario (MNR, Revolutionary Nationalist Movement) is a right-wing party in Bolivia. Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada, the MNR candidate, was elected president of Bolivia in 1993 and served until 1997, a period during which he expanded the neoliberal economic policies that came to be known as the New Economic Policy, repressed trade unions, and fired 30,000 miners from the state-owned tin mines. and the APRA in Peru.11Translator’s note: The Alianza Popular Revolucionaria Americana — Partido Aprista Peruano (APRA, American Popular Revolutionary Alliance) is the Peruvian section of the social-democratic Socialist International. Its successful presidential candidate in 1985, Alan García, served until 1990, and during his term presided over a Peruvian economy wracked by world-record hyperinflation, widespread corruption, and massive increases in hunger and social unrest. It participated in Congress throughout the 1990s as a partner in imposing neoliberal policies. Then, in the early years of the new century, the so-called progressive governments began to make adjustments as soon as the international crisis hit and the prices of raw materials exported from Latin American fell. Despite all the rhetoric about the “Great Homeland” and “Latin American unity,” they were unable to confront as a common bloc the scourge of foreign debt. What could the “vulture funds” and international organizations have done if Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador, Venezuela, Nicaragua, Bolivia, and Uruguay all failed to pay their fraudulent and usurious debts? There is no independent stage during which national independence can be conquered together with the local bourgeoisie and then a later stage during which to raise the struggle for socialism. Either the working class, leading all the exploited, takes the lead in the anti-imperialist struggle and seizes power, or our countries will continue with their descent and backwardness. Hence the importance of maintaining full political independence from these movements while confronting any attacks from right-wing forces.

Second, history has proved Trotsky right about Stalin: socialism cannot be built within the confines of a single country. We must end this system across the globe — as is evident from the international character of the productive forces that capitalism generates. Internationalism, which logically includes anti-imperialism, is today more necessary than ever.

Finally, the October Revolution pioneered the achievement of great conquests in broad areas of social life. Abortion was legalized in the USSR in 1920, while in the United States it only became legal in 1973 and in most Latin American countries the right to an abortion still does not exist. Measures were taken in the USSR to socialize domestic work and challenge the patriarchal structure of the bourgeois family. In the young Soviet Union, homosexuality was decriminalized; by contrast, the World Health Organization considered it a mental disorder until 1990, and in the United States, consensual sexual activity between people of the same sex was legalized nationally only on June 26, 2003 (previously it had depended on each state, Illinois being the first to repeat its laws persecuting homosexuality in 1962). Science and art gave rise to advancements that still influence different areas of culture. It is true that the Stalinist bureaucratic counterrevolution was accompanied by the elimination of many of these rights. Stalinism and all the Left that orbited it cultivated homophobia and took the patriarchal family as a model. All dissent in the artistic and scientific fields was crushed. Today, to think about revolution is — as it was for the Bolsheviks at the beginning of the October Revolution — to think about it in every area of life, and the struggle against the various oppressions imposed by the capitalist system is an integral part of the fight to revolutionize society as a whole.

But hasn’t it been said that the working class has lost its social power — some even say it is disappearing — and can no longer carry out a revolution? These statements are actually part of the ideological battle waged by capital, with the aim of undermining the morale of the workers — something to which the various trade union bureaucracies have adapted. If the current crisis has shown anything, it is that without workers the economy does not move. The working class has not disappeared but has been reconfigured, as has happened so many times in the history of capitalism and is happening again today as the crisis unfolds. The working class has enormous potential social power to smash capitalism, its governments, and its states. It is more numerous than ever before in its history. It is more geographically expansive, more feminine, more urban, on average poorer, and more multiethnic than 40 years ago, although more precarious. In the United States and in the principal countries of the European Union, what we can consider their “strategic positions” — that is, those sectors with a greater capacity to affect the production and circulation of capital — have changed, with transport and logistics gaining importance. In recent decades, a large part of industrial production has moved to China, Southeast Asia, and, more recently, to Africa, where there is a new proletariat in full swing. In many countries, low-wage and precarious sectors that have been considered “essential” during the pandemic are likely to gain in their organizational and fighting capacity, especially among the youth. At the same time, hundreds of millions of people constitute a kind of subproletariat, living miserably on the outskirts of the big cities or in the city slums, often depending for survival on state aid — where such a thing exists. This precariousness does not mean these sectors cannot organize themselves. In fact, they do so in different countries, whether in movements “for a roof over our heads,” of the unemployed, or of precarious workers. In our opinion, the lack of independent intervention and working-class leadership has not been a sociological problem but rather a political-moral one.

The neoliberal offensive, a real class war of capital against labor, not only succeeded in lowering the cost of labor globally but also produced significant levels of backward movement in class-consciousness and organization. The trade union bureaucracies and the Communist and Socialist parties practically surrendered without a peep and applied neoliberal policies themselves. The ruling bureaucracies in the Soviet Union and the countries of eastern Europe went over to the side of capitalist restoration, hook, line, and sinker — thus verifying Trotsky’s hypothesis regarding their social character. In China the capitalist opening promoted from above by the Communist Party itself was central to neoliberal expansion. This promoted the idea of an unbeatable and dominant capitalism and has imposed resignation to “common sense” about what is “possible.” But since the 2008 crisis, which showed the limits of neoliberal hegemony and of the capitalist expansion achieved with capitalist restoration in the bureaucratized workers states, something has begun to change even there. In the United States, Donald Trump has conjured up “socialism” as one of the evils in two of his State of the Union speeches. Various surveys reveal that the preference for “socialism” over “capitalism” is growing among American youth, even if their idea of socialism is rather vague. Many of these youth are now on the front lines of protests in the United States, where Black people and white youth have joined together to renounce the police and institutional racism. In Chile, as we pointed out, one of the models of world capitalism was challenged by mass action. It is true that along with all this we have seen a flourishing of all kinds of reactionary ideologies and leaderships that express fascist phenomena, such as that of Bolsonaro in Brazil. The reactionary anti-immigrant nationalism in the imperialist countries (and also in other countries that are not, such as Hungary and Poland, as well as the “anti-Indian” line of the Bolivian coup leaders, or all of Bolsonaro’s anti-communist rhetoric) are a right-wing expression of the crisis of neoliberal hegemony that we have seen since 2008, one of the trends toward political and social polarization that characterize our times and that, as we have pointed out, is likely to increase in the midst of an economic and social crisis with few historical parallels.

We know it is only in the heat of struggle that class consciousness can be revived and grow, not only for daily clashes at the level of the trade unions but especially for the political struggle, what Marx called the “real class struggle” — which is the fight for state power. At the same time, we know that the struggle alone is not enough; it needs to be preceded by clear revolutionary theory to be victorious. Revolutionary movements and revolutionary theory feed off each other. They need each other. Revolutionary theory will never be the work of an isolated individual; rather it will be the product of collective deliberation among those of us who want to end the capitalist system. Hence, we must build national revolutionary parties and a revolutionary international. These can be forged only if we actively in the daily struggle of the masses while continually developing revolutionary theory and strategy.

This is the framework in which we hope these writings of Leon Trotsky will not only introduce his work to new readers but also provide an essential input for intervening in the emancipatory struggles of the present.

Buenos Aires, June 3, 2020

First published in Spanish on July 5 in Ideas de Izquierda.

Translated by Scott Cooper

Notes

| ↑1 | Isaac Deutscher, The Prophet Outcast — Trotsky: 1929 1940 (London: Oxford University Press, 1963), 512. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Deutscher, The Prophet Outcast, 513. |

| ↑3 | Leon Trotsky, My Life, chap. 45, “The Planet without a Visa” (1930). |

| ↑4 | Translator’s note: Karl Marx, Capital, vol. 3, chap. 48, “The Trinity Formula” (1883). |

| ↑5 | ECLAC/ILO, “Work in Times of Pandemic: The Challenges of the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19),” in Employment Situation in Latin America and the Caribbean no. 22, May 2020. |

| ↑6 | Translator’s note: Lehman Brothers, then the fourth-largest U.S. bank investment bank and heavily involved in subprime mortgages, filed for bankruptcy in September 2008 — which is considered to have been one of the major precipitants of the global crisis that then erupted. |

| ↑7 | A term Ali coined to define the transformation of parties such as conservative and social-democratic or labor parties in two-party regimes into two sides of the same neoliberal political bloc. Translator’s note: Tariq Ali is a British-Pakistani writer and political activist (formerly a Trotskyist) who is a member of the editorial committee of New Left Review. See The Extreme Centre: A Warning (London: Verso, 2015). |

| ↑8 | Translator’s note: Carlos Menem was president of Argentina from 1989 to 1999. He identified ideologically with Peronism, the enduring Argentine political movement based on Juan Perón, who served as Argentina’s president from 1946 to 1955, was then overthrown in a military coup, and was again elected president in 1973 when open elections were again held. He died the next year, his widow Isabel took his place, and the military overthrew her government in 1976. Peronism is a corporatist-populist ideology aimed at enlisting the working class as part of a tripartite “coalition,” along with the state and the capitalists, to mediate tensions and ultimately ensure the continuation of the capitalist system. |

| ↑9 | Translator’s note: The Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI, Institutional Revolutionary Party) was founded in Mexico in 1929, and it held absolute power until 2000 under various names. Its primary ideology of corporatism was buttressed by alternating co-optation and violent repression of the working class, and it engaged in widespread electoral fraud over decades to maintain itself in office. Carlos Salinas de Gortari was the PRI president of Mexico from 1988 to 1994 and was involved in creating the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Ernesto Zedillo was the PRI’s last president during the uninterrupted 71-year period, serving from 1994 to 2000. |

| ↑10 | Translator’s note: Founded in 1941, the Movimiento Nacionalista Revolucionario (MNR, Revolutionary Nationalist Movement) is a right-wing party in Bolivia. Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada, the MNR candidate, was elected president of Bolivia in 1993 and served until 1997, a period during which he expanded the neoliberal economic policies that came to be known as the New Economic Policy, repressed trade unions, and fired 30,000 miners from the state-owned tin mines. |

| ↑11 | Translator’s note: The Alianza Popular Revolucionaria Americana — Partido Aprista Peruano (APRA, American Popular Revolutionary Alliance) is the Peruvian section of the social-democratic Socialist International. Its successful presidential candidate in 1985, Alan García, served until 1990, and during his term presided over a Peruvian economy wracked by world-record hyperinflation, widespread corruption, and massive increases in hunger and social unrest. It participated in Congress throughout the 1990s as a partner in imposing neoliberal policies. |