On April 30, 1970, President Richard Nixon announced he was ordering an invasion of Cambodia for the next day. The eastern part of Cambodia was full of troops from the People’s Army of Vietnam (the North Vietnamese) and their allies in the Viet Cong (from South Vietnam) — an estimated 40,000 — who used the region to launch attacks into South Vietnam. At the time, most Americans actually believed the Vietnam War was winding down thanks to the “Vietnamization” policy aimed at replacing U.S. combat troops with better-trained, better–equipped South Vietnamese forces. Cambodia was “neutral” and had its own civil war raging.

Nixon’s announcement shocked the nation. College campuses across the country erupted in protest the next day, May 1. At the University of Maryland, 1,500 students stormed the building used for Air Force Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC) classes.1ROTC was an on-campus program to train future officers for the U.S. military, and was compulsory for many male students on many university campuses until the 1960s. It was common to see students in military uniforms attending regular classes on the days of their ROTC classes. The program became a typical target of the antiwar movement on campuses. University of Cincinnati students were arrested when they held a sit-in downtown, at a major intersection, and blocked traffic. Tear gas scattered protesters on the Stanford campus in California. At Princeton, students skipped classes and called a meeting to advocate for a national student strike.2Eventually, nearly 900 university, college, and high school campuses were on strike in early May. The University of Washington’s “Mapping American Social Movements” project has a full list and amazing interactive graphic.

A meeting at Yale University that day was critical to the events that followed. Students from throughout New England and New York had already planned to be in New Haven that day for a demonstration against the trial of Black Panther Party leaders. Some 12,000 people mobilized, while thousands of soldiers and Marines were deployed nearby as a “precautionary measure.” The city anticipated a riot, but the rally was peaceful.

So many antiwar students in one place, from multiple campuses, created an opportunity. Hundreds convened a mass meeting at which they launched the National Strike Information Center (NSIC) as a way to promote and spread a student strike across the country. Brandeis students volunteered their campus as headquarters and for an information clearinghouse. Two nights later, the NSIC was up and running in the sociology building, thanks to a professor’s help.

Meanwhile, on May 1 at Kent State University in Ohio, about 500 students held a militant demonstration to protest the Cambodia invasion. History students buried a copy of the U.S. constitution — which they said Nixon had killed. A sign on a nearby tree read, “Why is the ROTC building still standing?” That protest broke up, but crowds gathered in town that night. There were confrontations with police. The mayor ordered bars closed, provoking anger. Tear gas was used. Then the mayor declared a state of emergency and asked the governor for assistance.

Getting Involved

Sometimes the best way to convey the significance of an event in history is through the eyes of an individual and the effect it had —- not because that individual’s own story is “important” but because the experiences we have as individuals often express larger social phenomena in compelling ways.

In this article, that individual happens to be me. I have a connection to the events of those days in early May that I think reflects what a lot of people went through, how their consciousness changed, and how the future course of the antiwar movement was shaped.

Before telling the story, it’s important to make clear that much of my experience is not unique. When I joined the Trotskyist movement a couple of years later, I met lots of other young people — similarly bold, brash, and a bit reckless — who had been radicalized by Vietnam. They believed, like me, that the war would keep going and we would be sent off to die a few years down the line. And I know of at least a dozen high schools and junior high schools that mobilized that May that aren’t on any lists I’ve seen — and at least five of those demonstrations were initiated and led by kids who were later my comrades in the Socialist Workers Party (SWP).

On May 1, 1970, I was a junior high school student, a day shy of my thirteenth birthday. That evening would begin a two-day celebration of my Bar Mitzvah. I was also very politically aware for my age — something that had already been getting me in trouble for years. I lived in Ossining, New York, a working-class town with a significant Black community about 30 miles north of Midtown Manhattan. I published a biweekly “underground newspaper” at school, four mimeographed pages with articles against the war and about our oppression as young students.

I watched Nixon’s speech and decided we needed to protest. But I was supposed to miss school that day to practice at the synagogue. Instead, I went to school just for the morning. My plan was to convince as many seventh- and eighth-graders as possible to walk out of school and march the 1.7 miles to the Post Office — the town’s only federal building — for a spontaneous antiwar demonstration. The Post Office was directly across the street from the high school, on Ossining’s main thoroughfare. I knew we’d get lots of attention and maybe some people would join us.

It took only 30 minutes to convince nearly 60 kids to join me. We left school and marched, chanting “U.S. Out Now!” and “No Invasion of Cambodia!” Two minutes later, the cops showed up. But we were fearless. They had no idea what to do, and ended up giving us an escort. Our loud rally on the sidewalk outside the Post Office drew another hundred or so students from the high school. I gave a speech, without a sound system. Afterwards, I went off for my studies.

I monitored the news over the weekend, but it was hard to do between a Bar Mitzvah and party. There was no Internet or 24-hour news cycle. I remembered that a friend in the town we’d moved from had a brother transferring to Kent State University — actually, a foster brother, because my friend was a foster kid. I wondered whether he was still with that family in Plainview, and I asked my mom whether I could make a long-distance call (it used to cost to call beyond your own town) to ask whether he knew anything. He didn’t, but we caught up.

A Student Uprising Grows

Campuses across the country were in motion. The Brandeis center was humming. Editors of college newspapers at Brown, Columbia, Dartmouth, Harvard, Haverford, Penn, Princeton, Rutgers, and Sarah Lawrence somehow held a phone meeting and agreed to publish a joint editorial in their next-day’s editions condemning the invasion of Cambodia and calling for a nationwide university strike to demand “an immediate withdrawal of all American troops from Southeast Asia.” It was significant that they didn’t demand “negotiations” to end the conflict — a position in the antiwar movement that was at odds with the “out now” perspective I supported. Also, the strike they called for wasn’t just for students. It was much broader, and pointed to what needed to happen beyond the campuses:

We must cease business as usual in order to allow the universities to lead and join in a collective strike to protest America’s escalation of the war. We do not call for a strike by students against the university, but a strike by the entire university — faculty, students, staff, and administrators alike.

At Kent State, the protest and subsequent “trouble in town” that had begun on May 1 continued over the weekend. That Saturday, merchants claimed “radical revolutionaries” were in town to destroy the city and university. The police chief claimed he had information that the ROTC building, the Army recruiting station, and other facilities were on a “destroy” list for that night. Crazy rumors swirled — LSD in the water supply, tunneling under a downtown store so it could be blown up, caches of weapons on the edge of town. The revolution was coming.

That night, when the Ohio National Guard arrived, the ROTC building was indeed on fire, and there was a large demonstration on campus. Tear gas filled the air; a bayonet wounded a student. The next day, Ohio Governor Rhodes held a press conference and spoke of a roving “dissident group” of “revolutionaries” out to destroy higher education in his state:

We are going to eradicate the problem. We’re not going to treat the symptoms. … They’re worse than the brown shirts and the communist element and also the nightriders and the vigilantes. They’re the worst type of people that we harbor in America. … I think that we’re up against the strongest, well-trained, militant, revolutionary group that has ever assembled in America.

Antiwar students were being compared to Nazis, communists, and Klansmen. Every base was covered to justify the violent attack against them that had been put on the agenda.

At the time, lots of members of state National Guards were student-age men trying to avoid being drafted and sent to Vietnam. Unlike in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, National Guard units were not deployed overseas. They typically practiced a couple of weekends a month and helped out with national disasters. When there were riots, they might be called in to supplement the police.

Debates in the Antiwar Movement

To understand why what happened the next day had such an impact requires some context regarding the Vietnam War and especially the growing movement against it. It is a rich and instructive history. The best book by far is Out Now! by Fred Halstead,3Fred Halstead, Out Now! A Participant’s Account of the American Movement against the Vietnam War (New York: Monad Press, 1978). a Trotskyist, SWP leader, longtime activist at the center of the antiwar movement, and the party’s presidential candidate in 1968. That was the year most everyone put their hopes for ending the war on Eugene McCarthy and then Robert F. Kennedy.

Space allows only a synopsis of how the war and the movement unfolded. President Lyndon Johnson used a false confrontation in Vietnam’s Gulf of Tonkin in August 1964 as the pretext to begin bombing North Vietnam, something that became regular. By early 1965, critics within the U.S. government were starting to question Johnson, who characterized the war as a fight to liberate South Vietnam from “Communist aggression.” The “domino theory” — let the Soviets or Chinese gain a footing anywhere and they’ll take over the world — was in full play.

By the end of 1965, there was a growing movement against the war on many college campuses. Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and others were organizing “teach-ins” that confronted U.S. policies through lectures and discussion. Small pickets and marches were taking place, most notably in Berkeley and New York City. At the same time, a “counterculture” was emerging and growing — hippies dedicated to the mantra of “turn on, tune in, drop out.” They were part of the antiwar movement, too, but went further — they despised everything associated with the “establishment” (sometimes characterized as anyone over the age of 30).

The antiwar movement, so closely associated with this “New Left,” took on a character of rebellion against “regular Americans” — whose sons were the ones coming home in boxes from Vietnam. It made winning working people to an antiwar perspective very challenging, as many saw antiwar demonstrators as a bunch of pot-smoking, acid-dropping layabouts who needed to get jobs and haircuts.

When Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke to a Chicago rally of more than 5,000 in late March 1967, many thought the tide would turn. He condemned the war for diverting funds from anti-poverty programs and noted that Blacks were being killed in disproportionate numbers in Vietnam. By late 1967, with nearly half a million U.S. troops in Vietnam and casualties already at 15,000 killed and 110,000 wounded, more people were beginning to question the war. The compulsory draft brought upwards of 40,000 young men into the Army every month, and the social cost was growing greater for the government — on top of the $25 billion yearly it was costing taxpayers, the equivalent of more than $193 billion today.

On October 21, 1967, 100,000 demonstrators traveled to Washington for a mass rally at the Lincoln Memorial. Some 30,000 marched across the Potomac to the Pentagon later that night, where there was a brutal confrontation with soldiers protecting the building. But this was still largely a movement of students and hippies.

The Tet offensive in January 1968 began to change that, making abundantly clear that U.S. imperialism was unlikely to defeat the Vietnamese people fighting for their liberation. The desperation among U.S. military leaders was apparent — some were so determined to win that they advocated bombing the country back to the stone age. A Gallup poll showed only 35-percent public approval for Johnson’s handling of the war. Soon, returning soldiers who had formed an organization called Vietnam Veterans Against the War buttressed the ranks of the antiwar movement. On television, parents around the country with sons overseas saw these men, many in wheelchairs, throwing away their war medals.

At the same time, the “New Left” continued to polarize the country with counterculture shenanigans that made it difficult to win working-class Americans to the cause. The Yippies ran a pig for president in 1968, mocking the bourgeois democracy most Americans cherished. When activists converged in Chicago at the Democratic National Convention and were beaten by rioting cops, many people were shocked — but many also thought they’d asked for it.

The 1968 election brought Nixon to the White House. He had promised to restore “law and order” — meaning an assault on the antiwar protests and the Black communities that had rioted after King’s assassination earlier that year. Once inaugurated, he escalated the war and instituted a draft lottery — ostensibly to eliminate inequalities in the conscription system. On May 22, the Canadian government announced that its immigration officers would not ask about immigrant applicant’s military status if they showed up at the border seeking permanent residence.

Within the movement, the New Left and the “Old Left” (mostly the Trotskyists of the SWP and the Stalinists of the Communist Party, USA) were fighting with each other, and the Trotskyists and CPers were fighting over what the main slogan should be: the anti-imperialist slogans “Out Now!” and “Bring the Troops Home Now!” (which would mean the immediate victory of the Vietnamese people) or the slogan that served the interests of the entrenched Soviet bureaucracy in Moscow, “Negotiations Now!” This became important to the upcoming Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam, demonstrations scheduled for October 15, when millions of students took the day off school, joined by lots of workers who skipped work to participate in local demonstrations and teach-ins (many for the first time).

One month later, a follow-up to the October actions brought a half-million people each to Washington and San Francisco for antiwar demonstrations organized largely by national coalitions with Trotskyists in key leadership roles.

That incomplete history brings us back to May 1970.

The Shots That Changed Everything

Back at Kent State, Monday, May 4 was another day of protest. At noon, about 2,000 students gathered, even though the university had distributed 10,000 leaflets saying the event was canceled. National Guard units attempted to disperse the students, but were met with rocks. Next came tear gas — which on a windy day was ineffective. Rocks were thrown again, and students chanted, “Pigs off campus!” Some lobbed tear gas canisters back at the masked guardsmen.

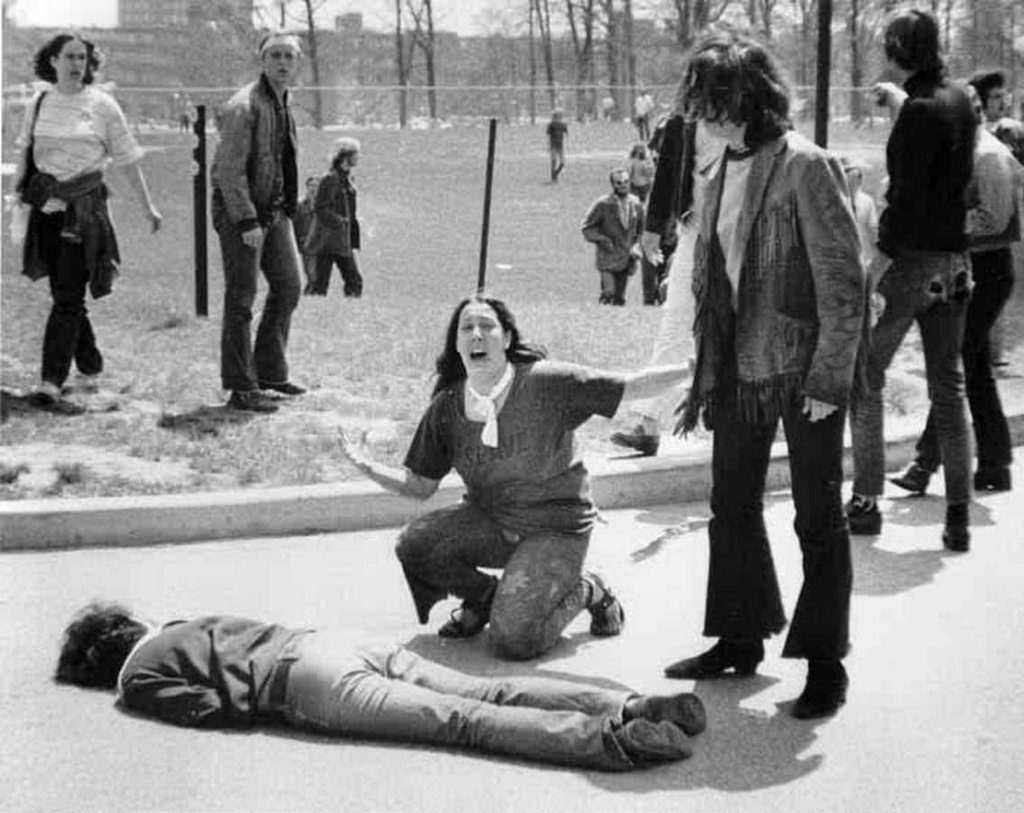

Soon, a group of the troops went up a small hill, kneeled down, and pointed their rifles. Eyewitnesses later said they assumed they wouldn’t fire, or it would be blanks. Then, a smaller group of guardsmen began to move. Suddenly, a sergeant began firing his .45 pistol at students. Next, some guardsmen nearest the students turned and fired their weapons. The shooting lasted 13 seconds, and when the smoke cleared, four students were dead or dying; nine lay wounded. Two of the dead were protesters; the other two, including a member of the campus ROTC battalion, had been walking between classes.

That day, I had skipped school, with two objectives: one was to cash in all the savings bonds I’d gotten at my Bar Mitzvah and buy classical records in New York City. The other was to go up to Columbia University and join an antiwar protest. I took the train to Manhattan, went to the record store near Grand Central Station, spent a lot of money for a teenager, arranged for the boxes to be shipped, and walked up 42nd Street toward Times Square to get some lunch — a bold move in 1970 — before riding the subway uptown. As I entered the southern part of Times Square, I saw the news crawl around what was then called the Allied Chemical Building (One Times Square today). I remember it said something like this: “Antiwar protesters shot at Ohio university. Dead and wounded.”

I was horrified. People looking up from the street were aghast. In Tad’s Steakhouse, where I could get a really cheap meal, it was on the radio. I listened as I ate. Then I decided to skip going to Columbia. What if they were shooting protesters everywhere?

Back at Grand Central, I took the next train, walked home to the apartment I shared with my mother and sister — with one set of grandparents upstairs, right above us. When the news came on that evening, the story of what had happened at Kent State was the lead story.

This time, I used my grandparents’ phone to call long distance. My friend answered. He told me his brother had been shot dead by the soldiers on campus. That most famous photograph, the one of a young woman kneeling over the dead body of a student, appeared on the front page of newspapers across the country the next day. The student was my friend’s foster brother, Jeff Miller.

The Aftermath

The murder of four students at Kent State had a profound effect on the direction of the antiwar movement. It immediately sparked the national strike called for in the joint editorial. Within less than two weeks, it engulfed nearly 900 college campuses in 49 states. Millions of students participated in their first protest. ROTC programs were eliminated. Some campuses shut down for the year. Actions were local and independently organized — aided by the NSIC, which emphasized three demands for the strike that were antiracist, anti-imperialist, and anti-repression:

That the United States government end its systematic repression of political dissidents and release all political prisoners, such as Bobby Seale and other members of the Black Panther Party. … That the United States government cease its expansion of the Vietnam war into Laos and Cambodia; that it unilaterally and immediately withdraw all forces from Southeast Asia. … That the universities end their complicity with the U.S. war Machine by an immediate end to defense research, ROTC, counterinsurgency research, and all other such programs.4National Strike Information Center, Newsletter #5 (Waltham, MA: 1970), p. 1.

The bourgeois media began to describe the strike in these terms: “The war has come home.”

But the impact of the killings at Kent State went well beyond the student population. When police in Chicago beat protesters in 1968, many Americans thought they got what they deserved. But killing students for protesting? That doesn’t happen in the United States! That’s what they do in countries like Mexico — where after a summer of huge demonstrations protesting the 1968 Olympics, the armed forces fired on protesters, killing hundreds of students and other unarmed civilians in the Tlatelolco section of Mexico City.

Other students were shot in May 1970 as well. They are often unknown or simply forgotten. But at Jackson State College in Mississippi, a predominantly Black school, there were two days of demonstrations for both civil rights and against the war. On May 14, police opened fire and killed two students and injured another 12. Even less known is that cops opened fire against protesters on the South Carolina State University campus in Orangeburg on February 8, 1968. Students had marched back to campus from a local bowling alley, where they were protesting racial segregation. Three protestors, all Black, were killed and 27 were injured.

After Kent State, I began to notice that the working people who frequented my grandfather’s small dry cleaning establishment, where I had a part-time job, would often tell me the May 1 protest I had organized — it had been in the local newspaper — was a good thing. These are people who not long before were telling my grandfather that I was a “little commie punk.”

It took a while before the working class began to turn against the war. Parents of soldiers increasingly took part in protests, as did workers — sometimes even with their local unions. But there was still a divide. Within days of the Kent State killings, on May 8, college and high school students protested at City Hall Park in New York City. About 200 construction workers were mobilized by the state AFL-CIO to attack the students. A two-hour “Hard Hat Riot” ensued, and about 70 people were injured. On May 20, at the same spot, about 150,000 people — mostly union members and their families — attended a pro-war rally in support of Nixon’s policies in Vietnam.

But the die had been cast, and the combination of students being shot, more boxes with bodies coming home, Vietnam vets expanding their protests, the “Pentagon Papers” being published, and more and more demonstrations all combined to make continuing that war untenable for the ruling class.

I could go on with a history of how the war finally did end, and how U.S. imperialism suffered an ignominious defeat that completely changed the discourse on war in this country, introducing the Vietnam Syndrome and “never get involved in a land war in Asia” — the “best known” of Vizzini’s “classic blunders” in the film The Princess Bride. But space precludes doing so.

What is important here are the lessons: how tides turn, how radicalizations happen, what kinds of organizing work best, and what a principled antiwar movement should stand for. They are lessons about the importance of independent political action at a mass level — after all, years of folding the antiwar movement into the election campaign for this or that Democratic candidate who promised “negotiations” never accomplished anything. The Democratic Party was, and remains, the graveyard of social movements.

I was already a budding Trotskyist in 1970. Over the next few years, I met so many young people who, like me, resisted the tremendous peer pressure to become part of the New Left and instead joined the Trotskyist movement. Not a single one of them left out Kent State when they told me of how they had been radicalized.

Notes

| ↑1 | ROTC was an on-campus program to train future officers for the U.S. military, and was compulsory for many male students on many university campuses until the 1960s. It was common to see students in military uniforms attending regular classes on the days of their ROTC classes. The program became a typical target of the antiwar movement on campuses. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Eventually, nearly 900 university, college, and high school campuses were on strike in early May. The University of Washington’s “Mapping American Social Movements” project has a full list and amazing interactive graphic. |

| ↑3 | Fred Halstead, Out Now! A Participant’s Account of the American Movement against the Vietnam War (New York: Monad Press, 1978). |

| ↑4 | National Strike Information Center, Newsletter #5 (Waltham, MA: 1970), p. 1. |