Today marks the 52nd anniversary of the official start to what would become a year-and-a-half-long occupation of Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay in 1969 by 89 Native Americans and their supporters. It was a remarkable demonstration of Indigenous resistance self-organization. Dubbing themselves the “Indians of All Tribes,” the occupiers attracted national and international support, inspired actions in the decades to come, and helped launch the Red Power movement.

The occupation of Alcatraz laid the groundwork for modern resistance to ongoing attacks against Indigenous people and land, and its legacy lives on in demonstrations such as the No DAPL protest at Standing Rock. While the occupation won some concessions from the capitalist state, its biggest impact was its role in building a militant Red Power movement and Indigenous struggles in the years to come. The action serves as a lesson in uncompromising resistance and self-organization.

The Context

The occupation of Alcatraz occurred in the context of a reinvigorated Indigenous struggle in the United States, continuing to weave the long thread of Indigenous resistance to genocide and colonization in what would become, through blood, theft, and displacement, the United States.

As the United States expanded its territory through land theft, the federal government coerced Native Americans to sign treaties, kicking them off of their ancestral land and onto the open-air prisons that would become known as reservations. In the late 19th century, the federal government commenced its “civilizing mission” to assimilate Indigenous people into the dominant white European culture, forcibly removing Native children from their families, outlawing the speaking of Native languages, and imposing education in “basic skills” so that they could be more easily to exploit Natives as domestic and manual laborers.

After brutal genocide that reduced the Indigenous population to historic lows, the population was able to regenerate to nearly 1 million by 1960 — by which time the government had changed its strategy toward Native Americans. Throughout the 1950s, the United States had sought to coerce some Native Americans to leave the reservations and move to cities, where they could become exploitated wage laborers, even offering some “help” with finding jobs and housing. Many Natives bought into this given the poverty conditions on reservations, including a lack of basic resources such as running water and electricity. After arriving in cities, many found that the training was inadequate, they typically received only one job referral (suggesting the program had been specifically set up to benefit certain employers, and financial assistance was scarce. But in the cities, many Indigenous workers were able to meet, discuss, and ally themselves with members of other tribes and people from other oppressed groups.

Native Americans living in cities were especially influenced by the social movements sweeping the nation, especially the burgeoning Black Power movement and the Black Panther party. At the same time, the United States was involved in a deeply unpopular war in Vietnam, which inspired massive student protests at colleges and universities. The social unrest this sparked led many to draw parallels between the suffering of the Vietnamese civilian population and the special oppression faced by minority groups domestically, whose members were being drafted in disproportionate numbers to fight the capitalist state’s war. From there, many radical groups, including one known as the American Indian Movement (AIM), began to take up the fight for Red Power.

Around this time in the Bay Area, many small groups were forming, typically with tribe-related names such as the Sioux Club and the Navajo Club. Initially coming together for dance, sports, and powwows. A number of them began to join together to address the unmet needs of their community.

Statements and Demands

The choice of Alcatraz was not random. Long before the arrival of colonizers, the island had been used by Indigenous people in the Bay Area as a place to camp out for hunting and fishing. A fort was built on the island during the Spanish-American war that later turned into a military prison. Indigenous people represented a huge number of those imprisoned — often for attempts to resist U.S. encroachment on ancestral land or theft of their children. In 1894, 19 Hopi men were imprisoned on Alcatraz for refusing to send their children to boarding schools. In 1934, Alcatraz became a maximum-security federal prison. For many Native Americans, it had become a symbol for the abuse of Indigenous people by the U.S. government.

After the Alcatraz prison shut its doors in 1963, Native Americans in the Bay Area began lobbying to have the island redeveloped as an Indigenous cultural center and school. A year later, five Sioux landed on the island to seize the land to be used for a university, citing an 1868 treaty that appropriated surplus land to Native Americans. While these early efforts received little publicity and were repressed by the state, they constituted the beginnings of a movement for Native Americans to reclaim the island from which prisoners could not escape — which led them to dub it “the Rock.”

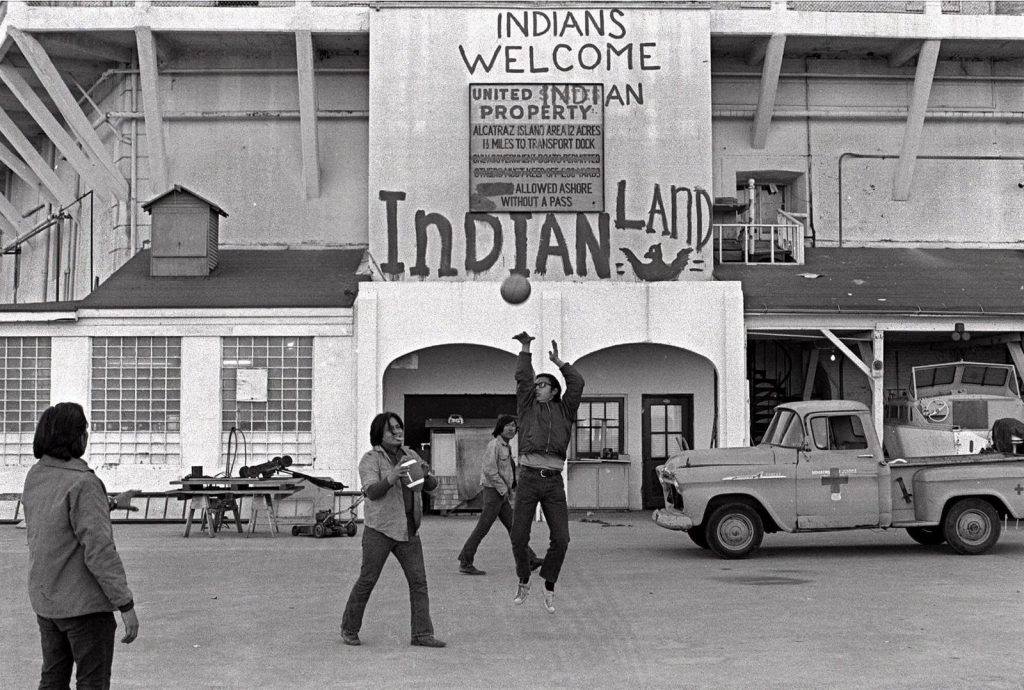

In late 1969, the city’s San Francisco Indian Center burned down, and Bay Area activists saw an opportunity to reassert their demands for land and sovereignty. In early November, a group of Native American activists boarded boats and rowed the one mile from San Francisco to Alcatraz Island. The group was led by Richard Oakes, a Mohawk who directed Indian Studies at San Francisco State College, and Grace Thorpe, daughter of Jim Thorpe, the famous Indigenous college football star and Olympic athlete. The occupation began with 89 activists, mostly Indigenous students, but rapidly grew — with 600 occupiers at its apex. Around 50 Native American tribes were represented on the island, calling themselves the “Indians of All Tribes.”

The occupiers at Alcatraz were self-organized. They elected a council, made all major decisions by vote of the complete group, and discussed and then allotted jobs to everyone: security, sanitation, daycare, school, housing, cooking, and laundry. On some days, there were as many as six meetings so that all decisions could be made by unanimous consent of everyone. They set up a school for the kids, and elders taught traditional native arts.

The occupiers symbolically offered to buy the island back from the U.S. government for glass beads and red cloth, replicating the “purchase” of Manhattan Island. In their proclamation, they were making an important point about colonization and its continued ramifications for Indigenous people.

Though the island was blockaded by the Coast Guard, supporters brought food and supplies to the protestors by canoe. Without electricity and running water, the conditions at the decommissioned prison were remarkably similar to those on many reservations. The occupiers issued a statement drawing the parallels:

We feel that this so-called Alcatraz Island is more than suitable for an Indian reservation, as determined by the white man’s own standards. By this we mean that this place resembles most Indian reservations in that:

1. It is isolated from modern facilities, and without adequate means of transportation.

2. It has no fresh running water.

3. It has inadequate sanitation facilities.

4. There are no oil or mineral rights.

5. There is no industry and so unemployment is very great.

6. There are no health care facilities.

7. The soil is rocky and non-productive; and the land does not support game.

8. There are no educational facilities.

9. The population has always exceeded the land base.

10. The population has always been held as prisoners and dependent upon others.

The occupiers announced that they aimed to establish a university, cultural center, and museum on the island, as well as a center for Native American Studies for Ecology, writing: “We will work to de-pollute the air and waters of the Bay Area … restore fish and animal life …” Though modest, the demand was a profound declaration of the inseparable connection between Indigenous struggle and the fight against environmental destruction.

The media and famous activists of the time were captivated by the occupation. The Philadelphia Inquirer highlighted the struggle with a positive — albeit also condescending — headline: “Occupation of Alcatraz Gives Indians a Sense of Pride and Achievement.” Celebrities such as the actors Jane Fonda, a noted anti-war activist, and Marlon Brando, who four years later refused an Academy Award and gave his speaking time to a Native American woman who had been at Alcatraz, visited the occupation and supported the struggle. This encouraging attention was helpful in keeping the state from a violent crackdown. President Nixon himself stated that it was “a new era, in which the Indian future is determined by Indian acts and Indian decisions.”

Winding Down

Inevitably, the occupation proved to be an unsustainable space for living, with no sanitation services, running water, or easy access to medical supplies and food. The composition of the groups began to shift as many of the students originally involved had to go back to school and were replaced with people who had not been involved in the initial occupation. The protesters began to align with two groups forming in opposition to Richard Oakes. Then, tragedy struck. Oakes’ 12-year-old stepdaughter, Yvvonne, fell three stories from the prison building and died days later from her injuries. It turned out to be the final blow. Communication from outside the island was cut off, which made it difficult to get basic supplies. Bickering and a general waning of morale persisted, and soon only 15 activists remained.

In June 1971, a year and a half after the occupation began, the occupiers were forcibly removed from Alcatraz.

Though temporary in nature, occupation is a powerful tactic that has been used extensively by Native American activists to draw attention to their struggles, usually surrounding the United States’ broken treaties with tribal governments. Prior to Alcatraz, Native American demonstrations and occupations had been primarily tribe-specific and local in nature. In 1964, Native Americans had “fish-ins” on the Nisqually River in Washington in defiance of court orders that banned Indigenous use of their waterways. The activists went to jail in the hopes of publicizing their protest, but their reach was limited in part because of its hyper-locality.

Alcatraz changed all that. The involvement of Natives from many different tribes, and its location right by a major city, helped expand the occupation’s reach and influence, nationally and internationally, and inspired actions in the decade to come. In 1972, members of AIM occupied the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) headquarters in Washington, DC. The BIA is the federal agency in charge of implementing federal policy on Native Americans — the same agency that carried out the pernicious policy of boarding schools throughout its cruel history. Though the federal government claims to regard Indigenous tribes as sovereign nations, itss policies are characterized by a long history of broken treaties that have left Indigenous communities with poor housing, underfunded schools, and widespread health crises on reservations.

The next year, AIM occupied the site of the 1890 massacre on the Pine Ridge reservation, during which several hundred Ogallala Sioux and their allies returned to the village of Wounded Knee. The catalyzing event was an effort to remove a corrupt, abusive tribal leader, Dick Wilson, but transformed into a symbol of the demand for Indigenous land and rights. The occupation ended after a marshal was shot and two occupiers were killed. Two AIM leaders, Dennis Banks and Russell Means, were indicted on charges related to the events at Wounded Knee.

Results and Influences

While the very specific demands of the Alcatraz occupation were ignored, the activists were still able to force the state’s hand at making some small concessions for the broader Red Power movement. The Nixon administration returned some large swaths of land to tribes in New Mexico and 40 million acres were given back to Alaskan Natives. The biggest concession was the 1975 Indian Self-Determination Act that increased tribal control over some federal funds and programs.

The more radical sectors of the movement, those most involved in AIM, saw these small allotments of territory and power as an attempt to placate Natives and stifle activism. The larger systemic problems were never addressed. The biggest demand — dismantle the BIA — was completely ignored; in fact, the way the small reforms were implemented actually bolstered the U.S. government’s legitimization of its colonization department.

While the Red Power movement fizzled out during the 1970s, threads of continuity can be found in Native American struggles to this day. Indigenous communities across the globe are in the vanguard of the environmental movement, and are at the forefront as water protectors in the United States. The struggle over the Dakota Access Pipeline and Line 3 were spearheaded by Indigenous community members, who have risked their lives and freedom as Big Oil continues to seize their ancestral lands and contaminate the water and soil.

As global leaders spit lies and sacrifice Indigenous people with sham climate policies such as carbon trading markets, we must carry on the legacy of the Alcatraz Occupation by standing in uncompromising solidarity with Indigenous land defenders and water protectors today.