As we write these lines, Latin America has entered the same path that has been shaking France, Sudan, Algeria, Catalonia, Ecuador, and Chile. The winds of class struggle, which blew for the first time in years in the Arab Spring, spread across Europe and reached our continent. The general economic crisis that began in 2008 has given rise to different expressions of organic crisis, including different levels of social and political polarization.

The exhaustion of the economic and political project of neoliberal hegemony has paved the way for extreme right-wing populist governments, but has also given rise to ideological expressions of progressive and left-wing criticism of this decadent social order that is sustained by exploitation and oppression. The resurgence of the class struggle places on the agenda a rearmament — theoretical, political, and strategic — to enable a profound transformation of society. This is a time for revolutionaries.

In the current scenario, Black people, as well as immigrants, are among those who most feel capitalism’s terrible effects and, as throughout history, they are occupying the most prominent positions in the class struggle. Eleven years after the the capitalist crisis began, the so-called “globalizing consensus” has given way to a resurgence of nationalist and xenophobic, anti-immigrant, and racist discourse projected across the globe by figures such as Trump in the United States, Salvini in Italy, and Bolsonaro in Brazil. The effects of the capitalist crisis are materialized in horrible scenes of immigrants who die as they attempt to cross the Mediterranean or Mexico’s border with the United States, and in the establishment of concentration camps to which they are sent when they arrive in Europe.

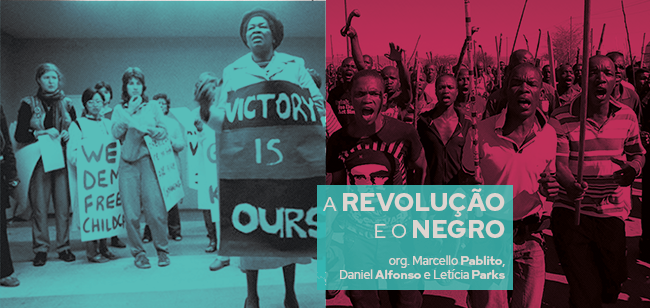

In the heart of imperialism, the police continue to murder Black youth systematically, including Mike Brown, Eric Garner, Philando Castile, and many others. In the United States, thousands of Black people have taken to the streets chanting “Black Lives Matter!” Their voices have echoed in the heads and souls of oppressed people around the world. Under the continuing apartheid in South Africa, the symbol of British imperialist oppression was challenged head-on in one of the most important student mobilizations of the decade. “Rhodes Must fall!” and then “Fees Must fall!” were the slogans of a movement that radicalized its demands by questioning the very symbols of imperialism (represented in the statue of the English colonialist Cecil Rhodes) and successfully forcing the University of Cape Town to give regular employment contracts to outsourced workers. In Marikana, also in South Africa, hundreds of miners confronted the British mining company Lonmin’s thirst for profits, fighting heroically for their demands through months of protests and dozens of deaths and injuries. The security forces in both cases responded with massacres, reminding everyone that Sharperville is not so distant in the past.1Translator’s note: In March 1960, police opened fire on demonstrators protesting the notorious “pass laws” outside a police station in the South African township of Sharpeville, killing 69 and injuring 180 — many of whom were paralyzed after being shot in the back as they fled the attack. The massacre triggered protests, strikes, and riots, culminating in the declaration of a state of emergency and massive detentions. It also sparked international condemnation, sympathy demonstrations around the world, and is largely considered the turning point at which South Africa began to be isolated in the international community. March 21 is now a national public holiday commemorating the massacre and honoring human rights. As C.L.R. James makes clear in his beautiful text “Imperialism in Africa,” written in the early years of World War II, the interests of the African people are diametrically opposed to those of imperialism.2Cyril Lionel Robert James (1901–1989), better known as C.L.R. James, was a Marxist writer, historian, and thinker from Trinidad and Tobago who lived most of his life in Britain and the United States. He was part of the Trotskyist movement for several years, but broke with Trotskyism in the early 1950s over differences on a number issues, including the characterization of the Soviet Union as a bureaucratically degenerated workers’ state — a position then defended by the U.S. Socialist Workers Party (SWP) of which he had been a part.

The execution of black councilwoman Marielle Franco in Brazil continues as an open wound from the institutional coup. The murder of capoeira master Moa do Katendê symbolized the emergence of a racist extreme Right and was a successor of the institutional coup against Dilma Rousseff. The state repression that takes the lives of young black women like Agatha Felix, only 8 years old,3Translator’s note: Agatha Felix was shot in the back by police in a Rio de Janeiro slum in September 2019 while riding a minibus with her mother. The police were chasing and firing at two men on a motorbike. Widespread protests blamed the shoot-to-kill policy of the Rio governor, Wilson Witzel — an ally of Bolsonaro who was elected on a platform of promising to “slaughter” drug dealers. and the terrifying unemployment rates and precariousness of work that mainly affects Black youth in Brazil are emblematic of how the rise of racism is materialized in daily life in the context of an economic crisis.

Those who keep their eyes open and their senses even a bit alert realize that our capitalist society cannot guarantee the minimum conditions for a life of dignity for the vast majority of the population. The resurgence of socialism as a reference for a different society is one of the greatest expressions of discontent with capitalism, both with the capitalist present and what the system promises for the future. The emergence of new processes of class struggle at the international level also opens the way for confronting racism, xenophobia, and patriarchy with renewed force, especially among the youth. This is gaining ground in society — often outside the traditional trade unions and parties of capitalist democracy.

Since it first began to emerge a few hundred years ago, the development of capitalism has transformed humans’ relationship with nature in unprecedented ways — combining creation and destruction, giving shape to social classes, and differentiating them one from the other on the battlefield of history.

One way capitalism expanded its relations of production was through the violent destruction of societies on the African continent. Taking Black men and women across an unknown horizon and transforming them into commodities was made possibleby a level of violence and oppression that even the tremendous numbers involved falls short of conveying. The continuing development of the productive forces paved the way for the combination of advanced technologies with the most brutal forms of domination by some humans over others. One of the articles in this book, “When Anti-Negro Prejudice Began,” explores this theme and, based on earlier contributions, relates the emergence of racism to the initial steps of capitalism.

Racism was at the center and at the service of the nascent bourgeoisie’s tireless search for political power that corresponded to its growing economic role in relation to the nobility. This is one of the conclusions of “Revolution and the Negro” by C.L.R. James, the opening article that gives this book its name. The reader will find others, but we advance one that seems essential: Black people will play a decisive role in the construction of socialism, even more than their monumental influence on the course of capitalist development.

In the midst of the French Revolution that began in 1789, the greatest bourgeois revolution in history, the Black people of Saint-Domingue [Hispaniola] achieved their freedom by liberating themselves from the political shackles of the French colonizers. At a time of profound transformations, the island’s slaves provided one of the greatest examples of the struggle for freedom humanity has ever known by abolishing slavery and guaranteeing their political liberty. Before any other regional elite could separate itself from the immediate interests of its colonizing power, the slaves led by Toussaint L’Ouverture and Jean-Jacques Dessalines realized that to exist without the bonds of slavery would require fighting the very empire that cried out “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity” but did not extend those words to the Haitian slaves. And so, the insurgent slaves imposed the first defeat on Napoleon and his army, Europe’s most powerful. Haiti emerged as a cry for freedom in colonial America.

Reducing the role of Black women and men in the development of capitalism to slave labor is a narrow exercise encouraged and spread by the dominant ideology to establish a subordinate place in human history for the masses of Black people. Among so many examples, was not the impact of the uprising in Haiti, in the midst of the Atlantic colonial powers’ struggle for hegemony, immense? Did the news of a country governed by Black not spread panic among all the colonial elites?

Revolutionaries informed by the lessons of the slave insurgents wrote the articles in this book. In the words of C.L.R. James: “Before the revolution they had seemed subhuman. Many a slave had to be whipped before he could be got to move from where he sat. The revolution transformed them into heroes.”

The heirs of Toussaint and Dessalines, Zumbi and Dandara,4Translator’s note: Zumbi was a Brazilian of Kongo/Angolan origin and a leader of 17th-century resistance to slavery of Africans by the Portuguese. He was also the last king of the Quilombo dos Palmares settlement of Afro-Brazilians that had liberated themselves from slavery. Dandara, Zumbi’s wife, was a renowned warrior against the colonizers who, when arrested in 1694, famously committed suicide rather than returning to slavery. Harriet Tubman, and all the anonymous pioneers of freedom, are among those who are fighting for the overthrow of the bourgeoisie, this class that has inherited the plantation, the whip, the libambo,5“The escape was punished with the libambo, an iron ring around the neck and a cane and a bell,” wrote Benjamin Péret, a French surrealist poet affiliated with Trotskyism, in his historical chronicle El quilombo de Palmares. torture, rape, and the Black Codes.6Translator’s note: Black Codes, prior to the Civil War in the United States, were common in many northern states. In the immediate aftermath of the war, Southern states established these laws as a way to govern newly emancipated slaves, restricting the scope of their “freedom” and especially to establish the low wages for which they could work.

We are approaching the end of the second decade of the 21st century. For more than 100 years, we have lived in a period of crises, wars, and revolutions. The demands of imperialism have led to horrors inflicted on Black people in every corner of the world. In the midst of World War I’s barbarism, the working class and its allies undertook the greatest liberating experience in history, seizing power in Russia in 1917 — prepared to make the greatest sacrifices in order to get a taste of what it would be like to be the masters of their own destiny. For this, they had a new type of party, revolutionary and internationalist, built under the auspices of Marx, Engels, Lenin, Luxemburg, and Trotsky.

Trust in the revolutionary power of the working class and oppressed peoples is an integral part of the entire history of Marxism. So, too, is understanding that class independence is imperative, as is the relentless use of resources and creativity for the conquest of political power and the possibility of building socialism on the ruins of capitalism. Here we mean real political power, based on the masses’ bodies of self-organization, the rational organization of production and the economy, the disarming of the bourgeoisie, and the arming of workers and poor people.

These are some of the requirements if we are to achieve a freer society. After all, how can you imagine society as a whole, or even just a country or region, being free if the police — the armed wing of the racist bourgeoisie — systematically murder Black people and their families, throw them in jail, and suppress and criminalize Black culture? Only a state controlled by the working class and poor people can guarantee that Black people can walk freely in the streets without fear of being killed. Without the weight of systematic oppression, the most distinctive expressions of Black culture can emerge in a creative, liberating explosion.

One of the greatest challenges of the struggle for socialism in the 21st century is to build a politics capable of responding to the demands of race and class from a revolutionary perspective. Those who close their eyes to the permanent tension within revolutionary Marxism in the face of this challenge are making a mistake. The texts in this book are a small sample of how the heroic struggle of Black people is inseparable from the class struggle, and of the invaluable role of revolutionary Marxism for both struggles. They were written after the creation of the first workers’ state in history and in the midst of the struggle of the Left Opposition and the Fourth International, led by Trotsky, against Stalinism’s reactionary course for the greatest revolutionary experience of the twentieth century.

The systematic repression of all the critics of that course was a fundamental part of the successive efforts of the Stalinist bureaucracy to perpetuate itself in power. Stalin’s obsession with killing the greatest living leader of the Russian Revolution, a leading name along with Lenin, was realized in 1940 with the assassination of Trotsky by Ramon Mercader.

It was in the living process of searching for a revolutionary orientation that could defeat imperialism and our class enemies that Trotsky and his allies confronted — politically, theoretically, and programmatically — Stalin and his “theory” of socialism in one country. This theoretical conception and the bureaucratic orientation adopted by the Communist International under Stalin’s leadership had a decisive impact on the failure to expand the revolution internationally. It also imposed a high price on the Black masses — one paid in blood. On the African continent, this policy would mean a decades-long delay in the independence processes of these countries. The Stalinist policy of “strategic alliances” with the national bourgeoisie (supposedly to accommodate a struggle against imperialism) would lead to the subordination of the enormous energy of the African masses to the narrow limits imposed by the bourgeoisies of their own countries, preventing these processes from advancing to the expropriation of the private ownership of the means of production that would open a new chapter free of imperialist domination over the continent.

Precisely because we live in an epoch of crises, wars, and revolutions, the imperative task of the working class is the conquest of political power. For revolutionary Marxists in the 21st century, this tension requires us to focus on the need for a strategy to connect the daily and partial battles with the political objective of seizing power as a necessary means to build a socialist society and communism. The challenges of the struggle against racism are an integral part of this tension. In this sense, Trotsky’s Theory of Permanent Revolution, developed and refined in the course of revolutionary processes, will also be invaluable.

Just as Black Haitians defeated Napoleon to gain independence and free themselves from slavery, the working class of the 21st century must take political power and defeat the racist bourgeoisie so a new society can be built.

One of the fundamental premises of the Left Opposition and the Fourth International is that there is no divide between countries that are supposedly ripe and unripe for socialist revolution. Stalinism declared Russia to be a supposed historical exception and guided alliances of Communist parties with national bourgeoisies around the world. In acute processes of class struggle, this orientation took a terrible toll, paving the way for counterrevolution. In other cases, such as in the United States in the first half of the 20th century, the historical logic of Stalinism, which saw feudalism in every corner where there was not developed capitalism, turned the correct policy of the right to self-determination for oppressed peoples into a policy of “stages,” full of skepticism about the role of Black people in building socialism.

For Trotsky, on the contrary, the defense of the right to self-determination was always related to the objective of increasing the revolutionary confidence of Black women and men in their own strength, in the fight against bourgeois chauvinism and its influence in the ranks of white workers, and in the revolutionary overthrow of the bourgeoisie.

In the arena of class struggle there is no finished answer; it is the very movement of history that provides the material for action. However, the struggle of the insurgent slaves, the workers, the poor, and the oppressed offers us valuable lessons. The texts that follow in this book are part of that whole.

The world has changed a lot since these texts were written. Urban centers have become even more important, as they address key problems such as the lack of housing and the basics of a decent life. The working class has expanded enormously, as never before in history — although it is increasingly fragmented (between subcontracted and regular workers; between natives and immigrants) and precarious (for which racism remains a fundamental component). Trade unions are increasingly integrated into the state, transforming themselves from tools of workers’ struggle and moving in the opposite direction, under the control of bureaucracies that act consciously to control and divide the working class, limiting their prospects to sectoral objectives and interim targets of each group of workers. We are at a moment marked by the emergence of social movements outside the trade unions and the traditional parties of capitalist democracy, in which the bourgeoisie can transform partial concessions into a means of containment, as a way to drain the strength and content from whatever is most subversive in the explosive revolt of women, Blacks, and immigrants, and reaffirm the bases of an exploitative social order.

The effects of this decadent society in Brazil, the country with the largest Black population outside Africa, leave their mark on the body of a young Black man beaten in a supermarket because he was alleged to have stolen four bars of chocolate. In the streets, the joy and energy of youth is lost in the statistics of tens of millions of unemployed, of an uncertain future that depends on a bicycle laden down with huge boxes emblazoned with the slogans of iFood, Rappi, and Uber. Delivery boxes on those small Black shoulders — that is the best prospect the capitalists have to offer, demanding 12 hours of work a day for one Real per kilometer traveled, in order to generate millions of dollars in profits .

But in the streets of the urban centers, it is also these youth that create their future every day, giving with their rhymes a breath of life to the older generations in a society that does not let us breathe. These youth proudly display their identity and their Black culture that can merge its energies with the social force of a powerful Black, female, and precarious working class that, like the street sweepers of Rio de Janeiro in 2014, can revive in their veins the boiling blood of freedom fighters.

This new reality makes the dissemination of the texts readers have in their hands even more necessary and urgent, since it poses the challenge that these lessons be translated into a strategy capable of organizing and uniting the working class (Black and white, men and women, immigrants and natives) with these youth. And with this power, revolutionize the trade unions, returning them to the class struggle and taking up demands such as those put forward by the Fourth Congress of the Communist International (as relevant today as back then) such as the struggle for equal pay for Black and white people (there is a 60% pay differential between Black women and white men) and for the unions to organize the working class as a whole. We hope this book will be read and discussed by all who see racism as one of the most perverse features of capitalism, and that the examples of the heroic revolutionary battles of Black people will give new generations of women, Black people, and youth the courage to follow this path and join in the urgent task of building a revolutionary party.

Finally, while it is not yet possible to know the future dynamics of events in Latin America, the resurgence of the class struggle will have a significant impact on the struggle in our country. Confidence in the strength of the working class will depend on politicizing hatred of racism. In Trotsky’s words, Black people will “furnish the vanguard” of the revolutionary struggle.

First published in Portuguese on November 13 in Esquerda Diário. Translated from the Spanish version in Ideas de Izquierda.

Translation: Scott Cooper

Notes

| ↑1 | Translator’s note: In March 1960, police opened fire on demonstrators protesting the notorious “pass laws” outside a police station in the South African township of Sharpeville, killing 69 and injuring 180 — many of whom were paralyzed after being shot in the back as they fled the attack. The massacre triggered protests, strikes, and riots, culminating in the declaration of a state of emergency and massive detentions. It also sparked international condemnation, sympathy demonstrations around the world, and is largely considered the turning point at which South Africa began to be isolated in the international community. March 21 is now a national public holiday commemorating the massacre and honoring human rights. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Cyril Lionel Robert James (1901–1989), better known as C.L.R. James, was a Marxist writer, historian, and thinker from Trinidad and Tobago who lived most of his life in Britain and the United States. He was part of the Trotskyist movement for several years, but broke with Trotskyism in the early 1950s over differences on a number issues, including the characterization of the Soviet Union as a bureaucratically degenerated workers’ state — a position then defended by the U.S. Socialist Workers Party (SWP) of which he had been a part. |

| ↑3 | Translator’s note: Agatha Felix was shot in the back by police in a Rio de Janeiro slum in September 2019 while riding a minibus with her mother. The police were chasing and firing at two men on a motorbike. Widespread protests blamed the shoot-to-kill policy of the Rio governor, Wilson Witzel — an ally of Bolsonaro who was elected on a platform of promising to “slaughter” drug dealers. |

| ↑4 | Translator’s note: Zumbi was a Brazilian of Kongo/Angolan origin and a leader of 17th-century resistance to slavery of Africans by the Portuguese. He was also the last king of the Quilombo dos Palmares settlement of Afro-Brazilians that had liberated themselves from slavery. Dandara, Zumbi’s wife, was a renowned warrior against the colonizers who, when arrested in 1694, famously committed suicide rather than returning to slavery. |

| ↑5 | “The escape was punished with the libambo, an iron ring around the neck and a cane and a bell,” wrote Benjamin Péret, a French surrealist poet affiliated with Trotskyism, in his historical chronicle El quilombo de Palmares. |

| ↑6 | Translator’s note: Black Codes, prior to the Civil War in the United States, were common in many northern states. In the immediate aftermath of the war, Southern states established these laws as a way to govern newly emancipated slaves, restricting the scope of their “freedom” and especially to establish the low wages for which they could work. |