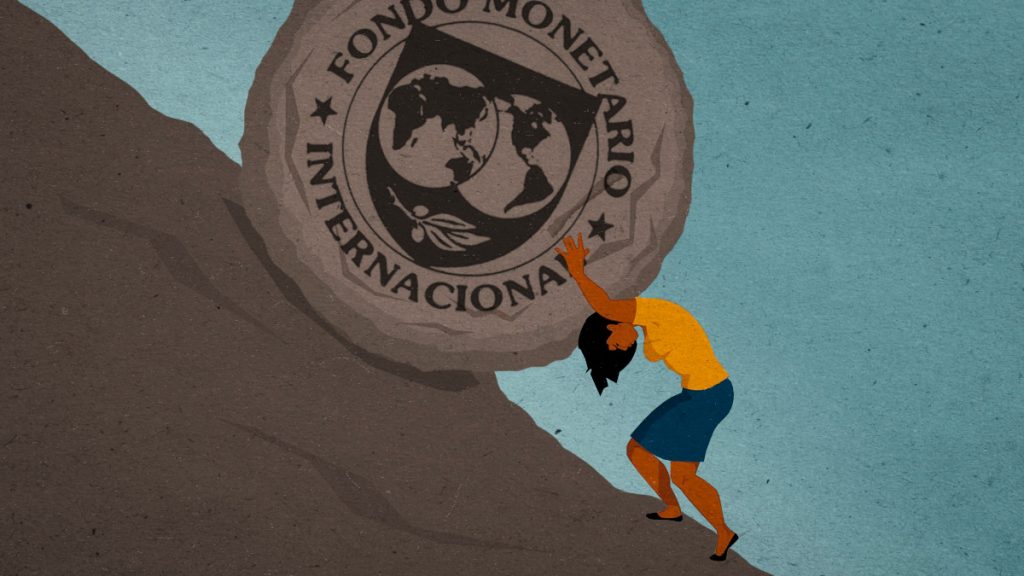

The IMF is trying to impose its usual adjustment plans, but in the last decade, it has done so with a particular gender perspective, especially after discovering that increasing women’s labor force participation could grow the economy, along with capitalist profits. In a March 2019 article in the IMF’s Finance & Development, Era Dabla-Norris and Kalpana Kochhar write,

We thought of gender inequality as largely an issue of social justice. It was only after we started delving into the topic that we came to realize that it is an equally significant economic issue. …

The IMF’s research highlights how the uneven playing field between women and men imposes large costs on the global economy. Early IMF studies on the economic impact of gender gaps assumed that men and women were likely to be born with the same potential, but that disparities in access to education, health care, finance and technology; legal rights; and social and cultural factors prevented women from realizing that potential. … In turn, these barriers facing women shrank the pool of talent available to employers. The result was lower productivity and lower economic growth. The losses to an economy from economic disempowerment of women were estimated to range from 10 percent of GDP in advanced economies to more than 30 percent in South Asia and in the Middle East and North Africa.

More recent studies suggest that the economic benefits of increasingly bringing more women into the labor force exceeds previous estimates.

The article, titled “Closing the Gender Gap,” is subtitled “The Economic Benefits of Bringing More Women into the Labor Force are Greater than Previously Thought.” Its authors — one a division chief in the IMF’s Fiscal Affairs Department and the other the director of the IMF’s Human Resources Department — suggest, among other things, that governments invest in infrastructure, support women entrepreneurs by providing greater access to finance, and promote equal rights for women.

Another IMF policy paper, “How to Operationalize Gender Issues in Country Work,” states,

Promoting global economic growth and stability requires an understanding of the underlying macro-critical factors, including the role of gender equality. Women’s participation in the labor market increases the size and talent pool of the labor force, helping to boost labor productivity and output. … Greater gender equality is therefore integral to delivering on the IMF’s mandate of promoting economic stability.1The authors also point out that the IMF, in 2014, initiated a research project focused on what it calls “gender budgeting,” aimed at making public spending more efficient and equitable.

As is evident in all its interventions in different countries, the IMF acts not only to defend the interests of creditors but also to safeguard the interests of globalized capital. During the 1990s it imposed austerity plans on countries around the world to pay off debts, the disastrous results of which forced the international lending agency to improve its discourse on poverty, inequality, and gender equality. This pinkwashing even goes as far as electing women to IMF management positions, who then show concern for and interest in the equality and development of other women.

Christine Lagarde was the first woman to head the IMF, serving as managing director from 2011 until 2019. Responsible for the agreements with the Macri government in Argentina when the country’s newest debt was taken on, she declared herself a feminist — even though she uses her first husband’s surname — and in 2018 was ranked by Forbes magazine as the third most powerful woman in the world. “Depreciating half of the world’s talent is a loss of economic prosperity for all,” she once declared, setting the gender tone that governs the organization.

Lagarde’s successor, Kristalina Georgieva, took over after serving as executive director of the World Bank. She feels similarly, and likes to repeat, “If women have equal opportunities to reach their full potential, the world would not only be fairer, it would be more prosperous as well.”

Again, economic prosperity is the goal, and that should be understood as the prosperity of the big capitalists.

About a decade ago, the IMF began to worry that the payment agreements signed by debtor countries should include women’s rights. Of course, what they consider a priority are the rights to sign contracts, have bank accounts, and own property. In the IMF article cited above, the authors point to the experiences of Malawi, Namibia, and Peru as examples, stating that to “promote equal rights for women” there must be “measures [that] include addressing laws governing inheritance and property rights.”

In many countries where the level of labor informality is even higher than in Argentina, or where large sectors of the population do not even use banks, the IMF is focused on removing whatever obstacles might exist for the poorest women to access microcredit and other financing for their own enterprises (India is a good example). In this way, women from the lowest-income sectors of the population are encouraged to become self-exploited “small entrepreneurs,” working tirelessly for a survival economy and, above all, indebted for life. This policy is now being promoted in Latin America, through international forums, organizations, and corporations, as the authors of Si nuestras vidas no valen, entonces produzcan sin nosotras2Alejandra Santillana Ortíz, Flora Partenio, and Corina Rodríguez Enríquez, Si nuestras vidas no vale, entonces produzcan sin nosotras. Reflexiones feministas sobre la violencia económica [If our lives don’t matter, then produce without us: Feminist reflections on economic violence] (Buenos Aires: Fundación Rosa Luxemburgo, 2012). write,

Although it takes up the spirit of policies aimed at the “economic development” of women in peripheral countries by creating microcredit policies, this agenda resumed its course in 2018 with the Women20 summit in Argentina that brought together “women leaders,” businesswomen, and leaders of the G20 member countries. From these narratives, “labor inclusion, digital inclusion, financial inclusion” and “rural development” of women “in situations of social vulnerability” was stated as possible through the promotion of “entrepreneurship.”

But, as the authors point out,

these labor modalities (which increased during the pandemic), far from creating new economic autonomies, deepen labor precariousness. This scenario unfolds in a region where the levels of informality, unregistered employment, low wages, and unemployment remain high, especially for women.

Sometimes, as in Jordan, Nigeria, and other countries where the IMF intervened, the organization expresses concern about unpaid care work, which falls mainly on women, and shows interest in creating an adequate infrastructure for the care and education of children, as well as introducing leave and other measures. But the IMF’s objective is not to recognize this free work but, more sordidly, to remove the barriers that may be keeping women from being exploited in the labor market. The authors of a 2019 IMF working paper even calculated that if unpaid work is reduced and redistributed, with a little public spending on some care infrastructure, there could be economic gains adding up to 4 percent of GDP. The IMF imagines that these services could be provided by private companies subcontracted by the state, which exploit other workers with low wages and precarious conditions, as well as by community organizations that guarantee soup kitchens and other social benefits — all at the edges of poverty.

Sometimes the IMF even encourages the state to favor tax breaks for families that hire domestic workers, as with the policy recently implemented by the government of President Alberto Fernández in Argentina. In that case, the measure was announced with great fanfare as helping female employees, but it has had no significant impact on the regularization of a sector that includes 16.5 percent of all employed women and 21.5 percent of overall wage earners — about 70 percent of whom still work without any benefits and have no rights to vacations, severance pay, or social security. In fact, their wages are so low that not even the subsidies to the employers can incentivize them to regularize their contracts.

There is no mention of women’s labor rights in any IMF document. When the IMF talks about encouraging the participation of women in the labor market, rather than printing a single word about the right to unionize or collectively organize, it instead suggests changes in employer taxes and social benefits — in short, more flexibility and job insecurity for women, and more favors for the bosses. It is clear that the IMF’s perspective on gender is nothing like that of the Latin American women’s movements, which have in recent years led important mobilizations in the region.

Section C of the memorandum signed by the IMF and Argentina in June 2018, titled “Supporting Gender Equity,” states, “Enabling Argentinean women to realize their full potential is not only a moral issue but also makes economic sense.” Along these lines, the government committed itself to

work to reform the current tax system by reducing disincentives for women to participate in the labor market; continue to implement our projects and initiatives on actions to promote equal pay and a more equitable paternity and maternity leave system; … continue to build infrastructure for childcare and early childhood education; require publicly traded companies to publish data annually on gender balance on their boards of directors and in their management positions; continue to work on our initiatives to combat gender-based and domestic violence and provide support networks for victims of such violence.

That first point is clear, just as mentioned above: eliminate taxes on employers that “discourage” them from hiring women — which is nothing more or less than greater flexibility with respect to labor. Some other points — like monitoring the “glass ceiling” of management and boards of directors — seem superfluous. Then there are things like building for care, and so on. These may sound very good, but they are proposed simultaneously with the IMF’s demand to reduce government spending — that is, cut public employment, postpone public works projects, and cut back on purchases of goods and services. It’s all a real contradiction in terms.

At present, thanks to the management of the Argentinean government of Fernández, extreme job insecurity has reached 44 percent. This cannot be attributed entirely to the pandemic; it also involves choices made in that specific framework. If we disaggregate the data, we see that the level exceeds 50 percent for women and is nearly 70 percent for young people. From the time of the Macri government until now, wages of the huge majority of informal workers fell by 31.4 percent, and the minimum pension — the one the vast majority of women have — fell by 27.3 percent.

What the IMF always demands is its structural reforms. It did so when it intervened in Argentina’s 2001 crisis, just as it had done in Mexico in 1982 and 1995, in the 1997 Asian crisis, and when Greece was at the epicenter of the 2008 European crisis. The loans always obligate the country to move forward with labor code reforms that allow for flexibilization and deregulation, as well as the privatization of public services and other policies that directly or indirectly affect labor rights. The IMF’s policies are so aggressive that they have even led to debates in international law over the legal and regulatory contradictions that they generate with the requirements of the International Labour Organization (ILO), which are generally resolved in favor of the IMF. As pointed out by Natalia Delgado of the University of Southampton,

Argentina is a historical witness of this fragmentation. On the one hand, the country has a solid labor code resulting mostly from workers’ struggles at different historical moments. It has also ratified a considerable number of ILO Conventions. On the other hand, the Argentinean state has systematically contracted debt with the IMF, which has imposed severe labor conditions to dismantle fundamental rights of the country’s workers and call into question the state’s international obligations with the ILO.3Natalia Delgado, “La disolución de los antagonismos entre el FMI y los derechos laborales” [The dissolution of antagonisms between the IMF and labor rights], in Derechos en acción: Edicion especiale: Fondo Monetario Internacional y derechos humanos [Rights in action: Special edition: The International Monetary Fund and human rights] (Buenos Aires: Revista Derechos en Acción, 2021), 479–516. Delgado also notes, “During the government of President Menem (1989–99), an emblematic economic model was imposed as part of neoliberal reforms, through the introduction of 20 drafts of labor reforms designed to reduce the costs of hiring workers.”

While right now the IMF is not explicitly demanding pension reform as part of the agreement, it is discussing this with Argentina’s government. Yet the fact is that pension reform has already been carried out, the income of retirees having been adjusted several times. The last adjustment came just as abortion was legalized in December 2020 — a spurious maneuver that the authorities wanted to pass secretly while we were mobilizing for abortion rights. Meanwhile, the labor reforms for which the right-wingers of the opposition, business groups, and the industry association is clamoring is stuck in Congress, but they are already trying to pass it off as an agreement — as Toyota is doing — with the endorsement of the bureaucracy of the automotive industry workers union (SMATA).

The Debt Is Owed to Us

Job insecurity, the wage gap, the lack of public services, and institutions that reduce the burden of domestic and care work are among the causes of inequality for women. While the IMF includes some of these issues in its new gender rhetoric, it chooses to ignore the fact that this gap with men, in different areas, is the same one we see between the lowest- and highest-income wage earners. The IMF’s reports blur class differences into a generalized average that prevents an accurate diagnosis of the needs of women in the most vulnerable situations. We find in the sectors where domestic and care work creates social wealth that goes unaccounted for in the national economy a fundamental factor for understanding impoverishment.

While more than 70 percent of men are active in the labor market, the number barely reaches 50 percent for women. When it comes to women living in households with higher incomes, though, we see that the number is above the average, at 62 percent, while less than 42 percent of women living in the poorest households are active in the labor market. These figures correlate with what we find if we analyze the hours dedicated in those households to unpaid work for the social reproduction of the family. While women at the lower-income end of the scale dedicate an average of more than eight hours a day to domestic and care work, women at the other end of the spectrum dedicate only four and a half hours a day.

Their precarious, part-time, or hourly jobs together bring in average monthly wages totaling just 36,000 pesos — the equivalent of US$357 and far less than what is required to cover the basic food basket for a household of three people. The decision to allocate more and more resources to paying the illegitimate and fraudulent debt means reducing or eliminating essential services for social reproduction and forces women to increase their hours of unpaid work at the expense of their wage-earning activity.

It is not difficult to imagine that in this situation it is women from the lowest-income sectors who are most affected by the housing crisis; their presence at the center of the land seizures spreading throughout Argentina are ample evidence. While the police in Buenos Aires Province and in the country’s richest city, Buenos Aires, have savagely repressed women and children as they’ve aided the speculation of the big real estate conglomerates, Martín Guzmán, the minister of economy, sent US$4.6 billion to the IMF. With that money, 131,000 houses could have been built. But that’s not all: Guzmán has already stated that he will pay another US$1.9 billion by the end of the year.

We Want a Life Free of Debt

What are the consequences of the IMF’s demand for a zero deficit? Reducing government debt means reducing the subsidies to privatized telephone and energy companies. But that will not affect the extraordinary profitability of these firms; instead, it will mean new and higher rates, something the government tried to avoid in the middle of the recent electoral campaign by increasing subsidies to the companies in October by as much as 125 percent. There is also a debate going on over whether the devaluation of the currency demanded by the IMF will be sudden or gradual. Either way, it is the exporters, banks, and big business that will benefit; wages will decline. And it will result in further slashes to spending on social benefits, which already suffered a 14 percent cut in this year’s budget.

“Serial payment” continues from one government to the next; the current government is torn between paying without delay or striking an agreement to pay over more time. It is possible, though, to put a stop to the debt’s eternal plundering. Investigating fraud is the first step to impose a sovereign refusal to pay the illegitimate and odious debt, through popular mobilization. Preventing the flight of capital and economic chaos through measures to defend national resources, such as nationalizing the banks and establishing a state monopoly of foreign trade under the control of working people, will require a struggle that will most certainly have women in the front lines.

It is we women who organized and mobilized massively in the streets to protest femicides, raising the cry of “Ni una menos” (Not one less) throughout the country; later, we draped the country in green until we won the legalization of abortion. It is we women who are already resisting job insecurity and low wages in the health sector; who led the large demonstrations against polluting extractivism in Patagonia, the Northwest, Cuyo, and Buenos Aires; who face the brutal repression of the police sent to evict from their precarious shacks those who have claimed land on which to live. It is we, the women of the social movements, from the poor neighborhoods, from the Left, who on the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women last week mobilized to demand no more femicides, murders of trans people, and sexist violence, and said no to the IMF and government adjustments.

“Today, Argentina is not in a position to pay the IMF debt. We say we cannot pay it again. Why don’t those who incurred it pay it?” asked Myriam Bregman in an early November interview. She is a revolutionary and member of Argentina’s National Congress, elected as a candidate of the Left Front — Unity (FIT–U). And she added, “They have to explain to us how the recipe of debt and capital flight, which cyclically generates economic and social crises, is going to have a different result this time. The agreements with the IMF always fail; the issue is who pays for it.”

A force of women is ready to fight the merciless future that is in store for us from the IMF and the governments that intend to pay the debt with the hunger and misery of working people and the increasingly precarious lives of women.

First published in Spanish on November 28 in Ideas de Izquierda.

Translation by Scott Cooper

Notes

| ↑1 | The authors also point out that the IMF, in 2014, initiated a research project focused on what it calls “gender budgeting,” aimed at making public spending more efficient and equitable. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Alejandra Santillana Ortíz, Flora Partenio, and Corina Rodríguez Enríquez, Si nuestras vidas no vale, entonces produzcan sin nosotras. Reflexiones feministas sobre la violencia económica [If our lives don’t matter, then produce without us: Feminist reflections on economic violence] (Buenos Aires: Fundación Rosa Luxemburgo, 2012). |

| ↑3 | Natalia Delgado, “La disolución de los antagonismos entre el FMI y los derechos laborales” [The dissolution of antagonisms between the IMF and labor rights], in Derechos en acción: Edicion especiale: Fondo Monetario Internacional y derechos humanos [Rights in action: Special edition: The International Monetary Fund and human rights] (Buenos Aires: Revista Derechos en Acción, 2021), 479–516. Delgado also notes, “During the government of President Menem (1989–99), an emblematic economic model was imposed as part of neoliberal reforms, through the introduction of 20 drafts of labor reforms designed to reduce the costs of hiring workers.” |