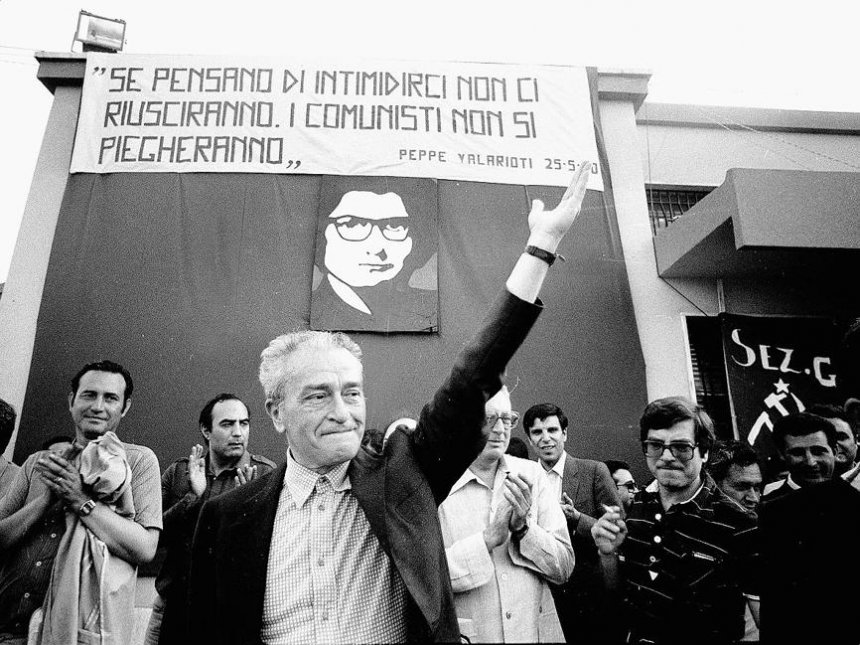

Obituaries and journalistic works have since multiplied for a man remembered as the “old-timer,” “guru,” and “secular pope of the Italian left.” Officials have also paid tribute, starting with Italian President Sergio Mattarella, for whom Ingrao was part of the “Italian patrimony,” as well as Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi, who built his career within the Democratic Party on the ruins of what remained of the PCI, describing Ingrao as “one of the most complex and most lucid witnesses of the 20th century and the left.” Even Giuliano Ferrara, a right-wing journalist and once-communist who abandoned Bettino Craxi’s Socialist Party to become a chief courtier for Silvio Berlusconi, evoked Igrao’s memory “with tenderness,” declaring in the Messaggero “that a piece of his life had disappeared.”

Such insistence upon unanimity is certainly understandable when considering the fact that Ingrao was, in effect, a staple personality of the left and the PCI, leaving his mark on the political and social history of the Italian peninsula from the beginning of the post-WWII era into the 1990s. In his youth, he was a partisan with the communist resistance. He later became an intellectual and leader of the PCI, a long-time member of Parliament, and eventually the President of the House of Deputies. Ingrao became an undisputed reference figure for a whole segment of “left-wing people” that had since been orphaned by large political organizations. However, this outpour of tributes fails to explain the specificity and the meaning of this public figure. If, as a number of pundits have recently claimed, Ingrao indeed represented “a symbol of the Italian left,” he is even more so when considered from all angles: as an incarnation of the resources, vitality, and numerous limits of this same left.

First of all, Pietro Ingrao’s history is inseparable from a very specific political culture of “left-wing togliattism.” This expression describes, in short, the attempt to find a “third way” (that has nothing to do with Lord Giddens, of course) between Stalinism and the PCI’s integral social-democratic and parliamentary turnaround, which was defended by the Giorgio Amendola-led right-wing. That was not only the horizon for Ingrao and the PCI’s left-wing, but also for the politico-intellectual group that he kept close to him, which founded the review, Il Manifesto in 1969 with the support of Ingrao himself while during his membering within the PCI’s Central Committee. The group was eventually excluded from the party.

Why “togliattism” and why “left-wing”? First,the strategy that Ingrao defended was theorized by Palmiro Togliatti, who conceived “an Italian way to socialism,” based on the gradual expansion of “social” bases and spaces of democracy within the Italian Republic, borne from the anti-fascist resistance – in reality, a reformist path, both domestically and internationally. Nevertheless, the “libertarian” sensibilities of Ingrao and Il Manifesto drove them to take a controversial distance from Stalinism (even more marked than the stance taken later by Togliatti himself), and from the mid-1960s, to adopt a “movement-ist” conception that turned Ingrao into the PCI’s privileged interlocutor with social and working-class struggles that developed force in Italy in the following decade.

The political phenomenon known as “ingraism” truly emerged in 1966, during the PCI’s XI Congress, when the communist leader openly claimed his right to dissent. For the first time, he stated to the presidency, “I cannot say that you have convinced me.” He thus became an explicit reference point for all those demanding from within the party to take distance from both Stalinism and the Party’s parliamentary and institutional downward spiral led by the right-wing Amendola. With the events of 1968 and later the Hot Autumn of 1969, a phase of social unrest marked by intense strikes and working-class struggles opened in Italy and lasted a decade. Simultaneously, the spontaneous class struggle developed throughout the country, as did the birth of a “union of councils”, of the student movement, organizations of the “new left”, and Il Manifesto in particular.

In this social climate of working-class and student ferment, Ingrao sought to dialogue within an increasingly fossilized and bureaucratized party, practically- and theoretically-speaking, with these phenomena. This approach was captured in the publication in 1977 of Masse e Potere (Masses and Power) — ingraism at its peak. In the book, Ingrao once again proposed the togliattian leit motiv of “progressive democracy” reduced in a movementist manner to “the organized link between representative democracy and grassroots democracy, aiming to foster the permanent projection of the popular movement within the State so as to transform it.”

There exists a point of convergence between ingraism, Il Manifesto, and other experiences born under the banners of “innovation” and anti-bureaucratism within left-wing Western communism of the 1960s and 1970s (ie., the British New Left Review); it is the inability to develop a critique of Stalinism and bureaucracy on a Marxist basis, thus precluding a revolutionary method of reconnecting the red wire of a history interrupted by the political defeat and police persecution of the Left Opposition in the Soviet Union in the late 1920s.

These different currents knew how to tackle the theme of revolutionary rupture in the context of economic and middle-class growth and the objective expansion of social rights, or a context of reforms-in-action. But they confined themselves, beyond the theoretical refinements and tactical positions, to an arena of a politico-strategic options associated with a reformist, social-democratic horizon – a sort of “left” reformism. It was this same reformism that would allow Fausto Bertinotti’s Communist Refoundation Party (PRC) to differentiate itself from the “social-liberals” of the Blairite yoke. It was not a coincidence that Bertinotti constantly used Ingrao’s political and intellectual heritage, despite the communist persona’s brief stay in the PRC between 2005 and 2008.

In the thick of this beautiful story, the crucial dissolution of the PCI would unfold. Decided in February 1991, this was the culminating moment in a process that began in 1989 with the “Bologna turn,” through which the PCI’s General Secretary Achille Occhetto made it known that the Party might need to change its name in the near future. Ingrao did not wish to break with the history of communism as a whole, nor liquidate it. He argued, criticized, and opposed this turn as he had done on numerous occasions in the past, but he did not break.

The Democratic Party of the Left (PDS) with Occhetto as Secretary formed, as did Armando Cossutta and Sergio Garavini’s Communist Refoundation Party soon after (subsequently joined by Bertinotti). Ingrao decided not to join PRC and instead stayed in PDS in order to animate the Democratic Communist Current until May 1993. He slowly came closer to the Communist Refoundation and eventually joined ten years later.

The electoral defeat of 2008 marked the first-ever exclusion of the communist left from Parliament in the history of the Italian Republic. Ingrao left the Communist Refoundation and called to vote for its former right-wing, which had recently become an autonomous party (Left Ecology Freedom).

After hearing of the communist leader’s death, Rossana Rossanda, a leading figure of the Il Manifesto group, wrote in Repubblica on the decisive moment that spurred PCI’s Congress of Dissolution: “to protect the party, Ingrao gave up trying to change history [because] the whole history of Communist Refoundation would have been different; perhaps to the left of what had been the PCI, there may have been a voice that could carry stronger than that of Garavini and Bertinoti. But Pietro did not wish to take that step.” Rossanda and her followers were utterly disappointed by Ingrao when, three decades prior, he voted in favor of the purge of members of the Il Manifesto group after previously supporting them.

The Ingrao was dotted with similar episodes of threats of rupture never fully carried out, of possible splits never realized, of Hamletian doubts that inhibited action. Although he represented a critical voice within the PCI’s left, in vital moments, Ingrao failed to express a true alternative and to regroup the social and political forces that could revitalize it.

He failed to do so against Stalinism in 1956, when Ingrao took a position against the Hungarian insurgents in support of the Soviet tanks in an editorial titled, “From one side of the barricade.” At the time, he was director of L’Unita, the central organ of the PCI. He would later regret this statement, but still agreed to sit on the Party’s Executive Committee for the following decade.

Ingrao did not know how to position himself in two other critical moments: first, during the purge of the Il Manifesto group from the party; second, when it was necessary to criticize the “historic compromise,” the strategy developed and defended by Enrico Berlinguer (Party Secretary), seeking an alliance with Christian democracy in order to create a government pact in the latter half of the 1970s. Ingrao was not a marginal personality at the time on the political checkerboard because he was the President of the House of Deputies.

Finally, he did not make a clean break with the PCI at the end of the 1980s, during the period leading up to the name change. Thus, he accompanied the party’s social-democratic and “post-marxist” identity change with his writings published after Masses and Power.

Beyond labels, the reality is what we have already shown: Ingrao was a social democrat like the overwhelming majority of his party’s leaders. Even at the height of his battle against Occhetto, his horizon remained that of the “German social democracy,” as he himself stated in an interview published in 2009 . Maybe a more “pure” and “authentic” social democracy, with a closer relationship to the labor movement than the PDS-DS-PD triad could ever boast — Italian “democrats” being, at least from the mid-1990s on, under the Blairite spell of social-liberalism (this time, indeed, connected with Anthony Giddens).

Hence, a reformist, though certainly “left-leaning.” Ingrao was awash in left-leaning reformism, in “devout wishes never translated into practice,” and in the inability to open alternative paths to those dictated by capital (as Greece has most recently exemplified). He can be remembered as a primary culprit, even when it comes to the disappearance of “the greatest Western communist party” and the conditions in which the Italian left finds itself today.

The original article can be found in French at revolutionpermanente.fr