In 1919, the example of the Bolshevik revolution spread all over the world. There were insurrections in Germany, Austria, Hungary, China, and Finland. Hundreds of strikes broke out in England. In Turin, the powerful Biennio Rosso (“Two Red Years”) posed workers’ power in every workplace, led by factory councils. The entire world was turning to the left, and the United States could not help but be a part of it. It was in Seattle that the revolutionary spirit struck hardest.

A coastal city in the state of Washington, in what is known as the country’s Pacific Northwest, Seattle at the beginning of the 20th century was already an important port. Its boom was fueled by shipbuilding and the timber industry. In addition, its geographical location made it the main port for trading with northern Asia and with Alaska.

The city’s economic prosperity drew a lot of local and immigrant workers, who found jobs mainly in the shipyards and sawmills. These industries underwent tremendous growth with the U.S. entry into World War I, with more ships for the Navy built in Seattle than anywhere else.

The great General Strike in “Queen City,”1Translator’s note: In 1869, a real estate firm in Portland, Oregon that was selling property in Seattle issued a sales prospectus titled “The Future Queen City of the Pacific.” The name stuck, and Queen City became Seattle’s nickname. In 1982, the local tourism bureau adopted “Emerald City” as a new name. which many historians consider to be the most important strike in U.S. history, did not happen in a vacuum. The American working class entered 1919 having flexed its muscles in hundreds of strikes in the three prior years from 1916 to 1918, involving more than 1 million workers. During that period, union membership grew by 400 percent. Despite brutal repression, American workers won the 8-hour workday and a long list of improvements in their working conditions. But above all, they gained both a more radical class-consciousness and greater confidence in their own strength.

The state of Washington was the epicenter of this radicalism. Once the United States entered the war, militant unionism intensified in Seattle. The rising class-consciousness of the workers clashed with the imperialist pretensions of the Woodrow Wilson administration, which was not about to permit any “anti-national” behavior in the midst of a world war.

President Wilson had won reelection in 1916 on a promise not to participate in the war. However, he quickly dropped that, and by 1917 the United States was dispatching its first troop ships.

The new war economy demanded wage freezes and military discipline in all the country’s factories and workplaces — to ensure a steady supply of arms, ships, and food for the front lines. This was done with the complicity of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) union bureaucrats, who helped the authorities control wages and block and suppress strikes.

For the U.S. government, Seattle was a Germanophile and pro-Bolshevik center. The Bureau of Investigation2Translator’s note: Established in 1908, this agency’s name was changed to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in 1935. in Washington, D.C. referred to Seattle workers as “the scum of the earth.”3Translator’s note: Cited in William Preston, Jr., Aliens & Dissenters: Federal Suppression of Radicals, 1903–1933 (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1995). In those years, the city boasted of a long leftist tradition, with the port owned by the city and women guaranteed the right to vote.

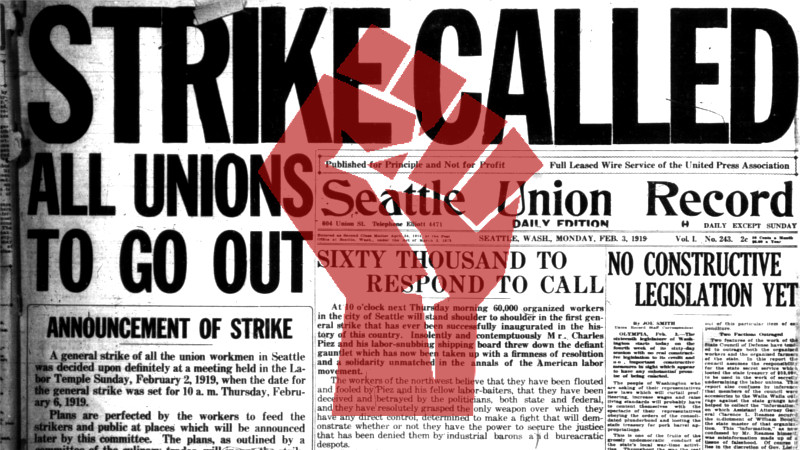

Historian Cal Winslow writes that the Seattle workers “created a culture of their own: unions that were ‘clean,’ not run by gangsters; a mass-circulation labor-owned newspaper, the Union Record, which became a daily in 1918, the only one of its kind; with socialist schools where classes were held both in their classrooms and outdoors; there were IWW choirs, community dances, and picnics. Utopian land-settlement schemes in Seattle’s vicinity drew in idealists and free-thinkers.”4Cal Winslow, “Company Town? : Ghosts of Seattle’s Rebel Past,” New Left Review 112, July–August 2018.

The main nucleus of the Socialist Party of Washington was in Seattle, with about 4,000 militant workers who paid party dues. They represented the left wing of the Socialist Party nationally, clashing with its mostly conservative national leadership on several occasions. Mostly, they criticized its leadership for supporting Samuel Gompers, the corrupt president of the AFL. The far left had won the party leadership in Seattle back in 1912.

Seattle was also the center of West Coast activity for the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), created by socialists, anarchists, and revolutionary trade unionists to challenge the bureaucratic and pro-employer AFL from the left. By 1917, the IWW’s membership was 150,000. The IWW had succeeded in organizing Washington lumberjacks and sawmill workers, winning wage and labor improvements for the union members.

The state of Washington responded to the uptick in class struggle, in the context of a world war, with increased repression. All the IWW leaders were prosecuted and imprisoned. In Chicago, 101 members were tried for sedition and conspiracy against the U.S. government; the state secretary of the Socialist Party in Washington, Emil Herman, was imprisoned on McNeil Island.5Translator’s note: McNeil Island is in Puget Sound, off the Seattle coast.

The combined situation of the influence of the October revolution, on the one hand, and the accumulated experience of the workers, on the other, was explosive. As early as 1917, on the eve of the Christmas holidays, the convergence between the revolution and the Seattle proletariat was sealed with the arrival in port of the Russian cargo ship Shilka, which had been “wounded” while sailing in the Pacific. Thousands of longshoremen, metalworkers, waitresses, sawyers, and workers from other trades came to the dock to give a big, warm welcome, with speeches and songs.

Seattle General Strike Is Transformed into Workers’ Power

The workers’ press in Seattle published Lenin’s letters. City delegates to the national AFL conventions were pressing their leaders to give official recognition to the new workers’ state in Russia. Dockworkers intercepted cargo containing rifles and ammunition bound for the counterrevolutionary White army in Siberia. The spark that ignited the gunpowder was the January 1919 strike, in which the 35,000 shipyard workers demanded the wage increase they had been promised for their war-related sacrifices.

Right off the bat, the shipyards sent their representatives to the Seattle Central Labor Council (SCLC) to demand it call a citywide General Strike in solidarity. Pressured by the rank-and-file, the Council agreed and immediately issued the General Strike call to the city’s 110 unions so the rank-and-file could decide.

The Central Labor Council was a coordinating committee of all the city’s trades unions created in previous years so each collective bargaining effort in a given industry would achieve a unitary agreement with the bosses. Both AFL and IWW delegates participated. The very existence of this committee revealed the class-consciousness that existed in unruly Seattle.

The working class voted overwhelmingly in favor of the strike. The Central Labor Council established a General Strike Committee in which rank-and-file delegates from all the trade unions participated. It was a genuine body of semi-soviet workers’ power. While it lasted, the General Strike Committee ran all of Seattle and its essential services — without the employers, without the political parties of the bourgeoisie, and without the police.

Because of the strike, more than 100,000 workers — a third of the city’s entire population — were suddenly unemployed. For years, the AFL had maintained racist divisions within the working class, keeping non-white workers out of its unions. That became impossible. Japanese barbers and restaurant workers were also joining the General Strike from their own unions. The very small Black population was doing the same.

Howard Zinn, in his classic book A People’s History of the United States, brings to life those six glorious days, when the working class made tremendous revolutionary progress:

The city now stopped functioning, except for activities organized by the strikers to provide essential needs. Firemen agreed to stay on the job. Laundry workers handled only hospital laundry. Vehicles authorized to move carried signs “Exempted by the General Strike Committee.” Thirty-five neighborhood milk stations were set up.

Every day thirty thousand meals were prepared in large kitchens, then transported to halls all over the city and served cafeteria style, with strikers paying twenty-five cents a meal, the general public thirty-five cents. People were allowed to eat as much as they wanted of the beef stew, spaghetti, bread, and coffee.

A Labor War Veteran’s Guard was organized to keep the peace. On the blackboard at one of its headquarters was written: “The purpose of this organization is to preserve law and order without the use of force. No volunteer will have any police power or be allowed to carry weapons of any sort, but to use persuasion only.” During the strike, crime in the city decreased.6Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States, chap. 15, “Self-Help in Hard Times” (New York: Harper & Row, 1980).

The working class’s potential to lead society was demonstrated. But with conservative leaderships at the head of their national unions and with the leadership of the Socialist Party still bound by social democratic prejudices, the example could not last. The Seattle Soviet could not, over its six days, withstand the pressure on the leaderships of the AFL and the hesitant IWW, as well as on the workers, and the experiment with workers’ power in the United States was put to an end.

To understand what happened, one must consider that alongside the General Strike Committee, a parallel steering committee known as “the Committee of Fifteen” was established, composed of the main representatives of the trade union aristocracy. This body was charged with undermining any challenge to the authority and anti-democratic measures of the labor leadership, so the insurrection posed by the General Strike Committee would not spread, either in length or breadth. In the end, the bureaucratic leaders secured that objective and kept the strike from extending throughout the vast region. Given an opportunity to turn the Seattle Soviet into a bastion for revolution in the United States, the union bureaucracy capitulated.

In the end, the workers returned to work with the realization that they had won none of their demands. Nevertheless, the experiment of the General Strike Council controlling the entire city for several days became a historical marker.

Today, that old experience of struggle should be an inescapable point of reference for a new generation of young people and workers in the United States who are engaged in a deep wave of mobilizations, a true rebellion against structural racism, driven by the slogan “Black Lives Matter.” This movement must be imbued with the lessons of the Seattle Soviet, which are more relevant today than ever before. Each new advance in the struggle of the masses presents “new old” challenges.

You may be interested in: Police Abolition, Self Defense, and Self Organization

One task for the current movement in the United States that cannot be postponed is to promote the emergence of union rank-and-files to lead an alliance with the hundreds of thousands of young people who are mobilizing throughout the country. In Seattle, they should be leading to create a police-free autonomous zone not just for a few blocks, but in the entire city — as was the case a hundred years ago. This is not an impossible task that must be postponed until the situation has “ripened.” Already, sectors of the working class are beginning to emerge that have mobilized despite the policies of the bureaucratic leaderships, as in Minnesota and elsewhere, and the debate is opening about the need for the police to be expelled from union federations under the slogan “cops are not workers.” Meanwhile, a number of Microsoft employees are demanding that the company cancel contracts with the Seattle Police Department and other state agencies.

Both the history of the Seattle Soviet and the experience of the last few weeks remind us that, in explosive situations, the consciousness of the masses can advance rapidly. The condemnation of the murder of George Floyd quickly escalated into a challenge against the entire police system, and from there to the widespread demand to abolish the police. All 50 U.S. states have mobilized and defied curfews.

We must also remember that the labor movement would not be starting from nothing. It has some important recent experiences: the teachers’ struggles of 2018–19 and, more recently, the historic strike of workers at General Motors, which was the longest auto strike in 50 years. Now, with the Covid-19 crisis in the United States, workers at different companies have led hard fights against the economic consequences being put on their shoulders.

Without a doubt, it is paramount that the youth leading the rebellion and the labor movement converge. To advance along this road, it is necessary to promote self-organization and political independence from the Democratic Party, with a socialist and revolutionary perspective.

First published in Spanish on June 21 in Ideas de Izquierda.

Translation by Scott Cooper

Notes

| ↑1 | Translator’s note: In 1869, a real estate firm in Portland, Oregon that was selling property in Seattle issued a sales prospectus titled “The Future Queen City of the Pacific.” The name stuck, and Queen City became Seattle’s nickname. In 1982, the local tourism bureau adopted “Emerald City” as a new name. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Translator’s note: Established in 1908, this agency’s name was changed to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in 1935. |

| ↑3 | Translator’s note: Cited in William Preston, Jr., Aliens & Dissenters: Federal Suppression of Radicals, 1903–1933 (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1995). |

| ↑4 | Cal Winslow, “Company Town? : Ghosts of Seattle’s Rebel Past,” New Left Review 112, July–August 2018. |

| ↑5 | Translator’s note: McNeil Island is in Puget Sound, off the Seattle coast. |

| ↑6 | Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States, chap. 15, “Self-Help in Hard Times” (New York: Harper & Row, 1980). |