DISPATCH FROM BRAZIL — The global economy is in intensive care, and the affects this will have around the world will cause suffering as in an earthquake. This is no less the case for Brazil, which was already forecasting zero economic growth in 2020. Can Brazil, which is so dependent on commodity exports, maintain its balance of payments for long in the face of shrinking world trade, falling commodity prices, and the economic weakness of its main trading partner, China?

A new global recession is the context in which the Covid-19 crisis and political crises are forming a feedback loop. This is having different political ramifications in each country. In China, Italy, and France, for example, the masses are imposing a temporary “political moratorium” on some of the most authoritarian measures, whereas in Brazil the developing health crisis is sharpening political and social polarization. The outcome remains to be seen, as does the path to extreme steps that would actually put the presidency itself into question.

Brazil already has more than 10,000 confirmed cases of coronavirus infection and at least 400 deaths from it so far. It is impossible to state with certainty the exact course the pandemic will take or the rhythms it will impose on the political crisis. The trend strongly suggests that the calamitous health situation will get much worse. That assessment accounts not only for the pandemic’s evolution around the world — with the United States and its 120,000 official cases already surpassing China’s — but also for the incompetence of officials at every level of government administering the response.

In Brazil this scenario is creating fissures within the regime, first and foremost among the Armed Forces — which have vaccinated themselves against Bolsonaro’s “denialist” line. The state governors are also working to use the situation to their advantage and project their own political positions in opposition to those of the federal government.

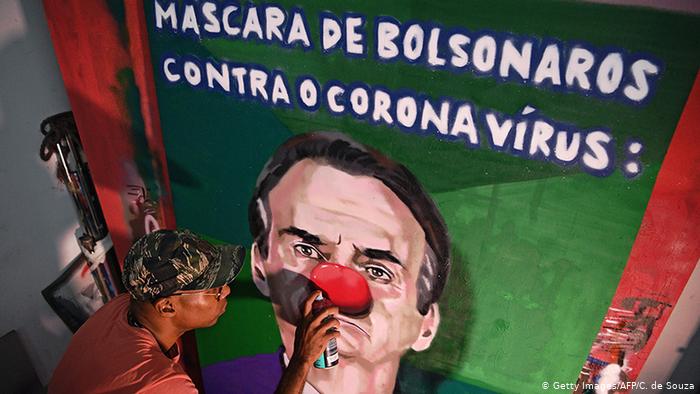

What Motivates Bolsonaro’s “Denialism”?

Jair Bolsonaro and his ministers Paulo Guedes (Economy) and Luiz Henrique Mandetta (Health) are leading the efforts not to combat, but rather to hide, the seriousness of the pandemic — and they are doing so with a sort of majestic ignorance. They bluff about some fictitious number of tests at a moment when the population needs massive testing more and more urgently. They take no steps to mandate that factories owned by the big monopolies produce masks, ventilators, and intensive care beds. They issue no plan to recruit trained health workers and students, much less to centralize the entire health system — including taking over private hospitals and clinics without compensation. To the irrational combination of testing and quarantine carried out by other governments, they simply counterpose disinformation and denial, which reflects all the class hatred of the backward bourgeoisie.

Bolsonaro claims to speak in the name of the self-employed, the informal workers, and the precarious youth who expend all their energy for iFood, Rappi, and Uber.1Translator’s note: iFood and Rappi are on-demand app-based delivery services. It’s pure hypocrisy. They are the victims of the labor reform and the “Green and Yellow Work Agreement” that legalized what were illegal jobs, a Bolsonaro flagship policy that has destroyed the most elementary workers’ rights.”2Translator’s note: The Carteira Verde Amarela of November 11, 2019, formally Provisional Measure No. 905, was a deregulation of Brazil’s labor laws that allowed companies to create new precarious jobs — up to 20 percent of their workforce — for people ages 18 to 29. The employers were exempted from the payroll tax on these jobs, the tax that funds social security, and they were handed a 75 percent reduction in the mandatory savings they were otherwise supposed to put aside for workers as part of an unemployment compensation fund. It also essentially ended penalties on employers for firing workers. To those workers, as well as to all others, Bolsonaro offered the “Provisional Measure of death,” a decree aimed at allowing the bosses to suspend work contracts for four months without remuneration. He had to back out of that measure, and then tried another decree that allowed a reduction in work hours and wages and the suspension of work contracts for two months, without employers having to pay into unemployment insurance.

Bolsonaro’s presidential pronouncement on March 24 was a monument to his hatred of workers. Showing his repugnance for their very lives, Bolsonaro said the virus would be momentary and declared that the economy must reopen. “Our life needs to go on, jobs must be maintained, families’ livelihoods must be preserved,” he said in a nationally publicized speech. “We must return to normalcy.”

It is a high-stakes gamble as the pandemic thrives in the open veins of a public health catastrophe “perfectly organized” by the capitalists.

Bolsonaro knows that his situation grows increasingly complex with an unfolding economic meltdown resulting from anemic growth, a new world recession, and the consequences of the pandemic. Meanwhile, many are dying in Brazil’s health cataclysm. The masses will point to Bolsonaro’s denial as proof that he is responsible for the tragedy. The Armed Forces are especially concerned about this possibility, and so while they are ruling out deposing the president for the time being — according to the Spanish newspaper El País — they are already holding meetings to map out a medium- and long-term scenario, which includes talks with Vice President Hamilton Mourão.

But there is a method to Bolsonaro’s madness. It is drenched with a willingness to sacrifice the lives of thousands of workers on the altar of capitalist profit. Rather than worrying about being held accountable by the people for Covid-19 deaths, Bolsonaro seeks to reactivate the economy without further delay to avoid becoming the political victim of a recession. In other words, workers may perish, but he’ll make sure the capitalists still get rich.

In a later national pronouncement on March 31, Bolsonaro was forced to retreat from his more aggressive denialist rhetoric. He said the pandemic “is a reality” and that his mission would be “to save lives without people losing their jobs,” calling to contain the coronavirus by forming a great “national pact with all institutions” (meaning state governors and the legislative and judicial branches). This shift reflected external and internal political influences. From the international point of view, Bolsonaro’s speech came just after Trump had also retreated from his “economistic” rhetoric. Given the tremendous increase in confirmed cases and deaths in the United States, Trump acknowledged that the country would go through “a very tough few weeks” and projected between 100,000 and 240,000 deaths, and so he did not expect to restart the economy in April as he had previously promised. Bolsonaro had to make a U-turn in accordance with the new White House policy and in view of the rising death toll in Brazil.

The Brazilian military was not some minor factor in Bolsonaro’s reversal. Aligned with the Pentagon, the leadership of the Armed Forces adopted a containment policy with respect to Bolsonaro’s denialism, putting Walter Braga Netto — an active-duty army general and current chief of staff of the presidency — in charge of relations between the executive and legislative branches and assigning him to command, “unofficially,” the efforts against the pandemic in accordance with World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines. Minister of Health Luiz Henrique Mandetta, who has a close relationship with Bolsonaro, works side by side with Braga Netto. The policy of the military in the Planalto presidential office responds to the moderating role of the Armed Forces in the crisis since Braga Netto took on this role in February. They have informally removed Bolsonaro from leading the crisis response, but for now the military does not want to remove him from the presidency: he continues to act as leader at all levels of national politics. They are keeping him in office as a way to avoid increasing tensions within the regime and generating discontent against the generals in the barracks, given Bolsonaro’s influence among officers and soldiers alike.

The instabilities in Bolsonaro’s conduct are a sign that tensions will continue and will be provoked anew. Despite the current moderating role of the Armed Forces, the military is already gaining strength. Braga Netto is accumulating power and can use that to his advantage in the course of the pandemic and the economic crisis — in response to which popular uprisings cannot ruled out.

Governors as Another Pole of a Coup, and the Military’s Growing Influence

Despite the masses’ enormous dissatisfaction with the government, the workers have not yet acted as an independent political entity, as an alternative to the bosses and Bolsonaro. That could change, since there is no wall that separates the working class from the self-organization that would be necessary to take solving the pandemic into its own hands. But that is not the current situation. In the absence of a working-class party, the main opponents of Bolsonaro’s executive branch are the state governors headed by São Paulo governor João Doria of the Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB). This camp was strengthened by the split of Goiás governor Ronaldo Caiado (Democrat, DEM) from the Bolsonist entourage.

The tension between the Bolsonist movement and the governors emerged with full force during a strike by state police that began February 19 in the state of Ceará, in northeast Brazil. Bolsonaro sent in troops to quell the strike and take control of the state’s security force, as well as to gain political advantage in the region. Then, as the coronavirus crisis erupted, governors found themselves having to counter the national government’s policy of a “return to normalcy” with their own rhetoric about “concern for the population” — expressed through the defense of quarantine and social isolation.

Governors have some real power with the fundamental pillars of the institutional coup d’état that is underway. The Supreme Court, first fiddle of the judicial authoritarianism orchestra, lost patience with Bolsonaro and linked itself with the governors. Rodrigo Maia, president of the chamber of deputies — the legislative branch whose approval is required for neoliberal measures such as the nefarious pension reform — also closed ranks with the governors. The coup press (Estadão, O Globo, Folha de S. Paulo) constitutes a choir of voices for the bourgeois regime.

Again, the influence of the Armed Forces within the government has become a major factor since Braga Netto was, in essence, transformed from chief of staff of the presidency to “operational president” during the pandemic. This is the culmination of the growing Bonapartist process of the institutional coup of 2016, with the incorporation of active army officers in positions closest to Bolsonaro. While maintaining Bolsonaro as president, they have removed him from immediate management of the crisis, adopting the line the governors had been following (those recommended by the WHO and specified by agencies linked to the U.S. Democratic Party establishment). The Armed Forces’ leadership preserves its own moderating power without removing Bolsonaro, but it does so by limiting his power in the midst of the pandemic and by aligning themselves with the governors, Congress, and the Supreme Court — a bunch of reactionary characters and institutions committed to the institutional coup of 2016. It is all part of what could be called a sort of “institutional-military Bonapartism.”3Translator’s note: The term, from Karl Marx’s 1852 work The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, refers to an authoritarian leader who emerges when different sectors of social classes are struggling against each other and are unable to find a way to impose representatives from their own ranks. In this context, a “Bonaparte” emerges who presents himself as an arbiter from above, separate from the dominant class and somehow not beholden to any of its institutions. A Bonapartist leader often leans on the military and seeks to give the executive branch of government more autonomy from other branches.

The top leadership of the Armed Forces distanced itself quite clearly from the Bolsonist rhetoric with the declaration of Army Commander Edson Leal Pujol, who posted a video on Twitter — only 85 minutes before Bolsonaro took to the airwaves on March 24 — that the fight against the coronavirus “is perhaps the most important mission of our generation.” Vice President Mourão, a general in the Army reserves close to the army leadership, is also restraining Bolsonaro. Mourão “corrected” the content of what Bolsonaro advocated, set forth the WHO guidelines, and showed evident displeasure with Bolsonaro’s confrontational pronouncement against the governors, even labeling the president’s remarks “crude” in an interview with TV Band.

All this expresses the diversity of interests across that part of the ruling class that opposes Bolsonaro’s approach to the pandemic and his orientation to the industrial and retail employers whose support he has enjoyed. Internationally, this opposition is aligned with the policy of the Democratic Party in the United States. Depending on how the crisis develops, the current policy of this wing of the regime may move from demanding that Bolsonaro step away from managing the crisis to demanding he step away from the presidency. Most likely, this will be clarified over the next few weeks.

Analyzing the dynamics of these conflicts back in May 2019, Daniel Matos wrote in La Izquierda Diario:

The development of the struggles within the coup regime is delineating two different projects of Bonapartism. One is the “imperial presidency” of Bolsonaro, which seeks to raise the executive branch as the absolutely predominant — and even messianic — institution of the regime to which all other “power factors” should be subordinated, using Lava Jato4Translator’s note: Operação Lava Jato (Operation Car Wash, because it was first uncovered at a car wash in Brasília) is an ongoing federal anticorruption investigation in Brazil launched in March 2014. First centered on money laundering, it was expanded to explore bribery allegations at the state oil company Petrobras, and then used to initiate an institutional coup through indictments and then imprisonment of a number of well-known politicians, including former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. Documents leaked to an investigative journalist in June 2019 reveal that a major motivation was to prevent Lula’s Workers Party from winning the 2018 presidential election that brought Bolsonaro to power. and the “street” as disciplinary tools. The other “institutional Bonapartist” project is the one in which the coup leaders of the old traditional parties (now largely put under the hegemony of the DEM party and with Congress as their “center of gravity”), in an agreement with other “power factors” (the Supreme Court, big media, and an element of the Armed Forces leadership), seek to constrain Bolsonaro’s power within the framework of the other institutions that were part of the coup.

Since that time, international condemnation of the Lava Jato judicial operation and the crisis over the Bolsonaro clan’s involvement in the assassination of Marielle Franco5Translator’s note: Marielle Franco, a city councilor in Rio de Janeiro from the Socialism and Liberty Party(PSOL) and strong critic of police brutality and the government’s extrajudicial killings, was gunned down on March 14, 2018, while being driven in a car after giving a speech. A year later, two former members of the military police were arrested and charged with her murder. They had ties to Carlos Bolsonaro, the president’s son, and had been photographed with the president. One was even his neighbor at a luxury apartment complex in Rio. put a halt to some of the excesses of presidential Bonapartism within the institutions, while also pushing the political regime further to the right, with the entry of more active-duty officers from the Armed Forces into high positions in the Planalto. With the emergence of genuine antagonism between the Bolsonist presidential Bonapartism and the increasingly influential institutional Bonapartism, there is a change in the composition of the forces in the second of the two bourgeois projects described above. At the same time, the legislative branch — which headed up this pole of the coup during 2019 — has ceded leadership, at least temporarily, to a sector of the governors supported by the highest leadership of the Armed Forces. They play a role in the two distinct projects based on the legacy of the institutional coup and its reactionary reforms.

Regardless of any difference over the way to organize the quarantine — whether it is a “horizontal” one that restricts movements more severely or a more “vertical” one that focuses on isolating the elderly — the truth is that despite their confrontational discourse, Bolsonaro and the governors are both coupists seeking to unload the costs of the pandemic onto the workers. Neither reactionary bourgeois camp offers a path forward to a progressive solution for the workers, who will suffer the most from the economic and health effects of the pandemic.

The fight to guarantee that all the resources that could save lives and confront the other effects of the pandemic — this fight can be waged only if it is taken up by the workers themselves, against Bolsonaro, the governors, and the capitalists.

Should the Slogan Be “All United against Bolsonaro”?

Fighting Bolsonaro in an alliance with the governors, legislators, and the entire cabal of institutional Bonapartist coupists means abandoning any vestige of class independence in the name of a “broad front against Bolsonaro.” That would only strengthen state authoritarianism against the exploited and oppressed. Measures taken by the governors, such as quarantining without tests, which diminishes the efficacy of public health efforts against the pandemic, along with their refusal to provide sufficient masks, ventilators, and beds, unify the state executives with Bolsonaro in their contempt for the people. A real battle means separating the workers from every faction of the bourgeoisie.

By differentiating itself from Bolsonaro’s policy, the Workers Party (PT) has positioned itself as the “left wing” of the policy carried out by the governors and institutional Bonapartism along with the redoubled influence of the military — which, as Lula says, “takes more responsibility” than the federal executive. Lula exchanged praise with right-wing governor João Doria on social media, widely publicized in the press as a move to isolate Bolsonaro. The PT is even self-restrained with respect to offering radical alternatives to what Bolsonaro is doing. In the four northeastern states it governs, the PT has refused to take any forceful measures: no mass testing, no centralization of the health system, no preventing the layoffs that continue to plague the region’s population. This PT policy is expressed even more clearly in the line taken by the trade union confederations it influences, the CUT and the CTB.6Translator’s note: The Central Única dos Trabalhadores (CUT, Unified Workers Central) is Brazil’s main national trade union confederation. The Central dos Trabalhadores e Trabalhadoras do Brasil (CTB, Central of Male and Female Workers of Brazil) is a confederation linked to the Communist Party of Brazil (PCdoB). The two trade unions signed a joint communiqué in which they ask that “the Congress assume the leading role” in confronting the pandemic, along with “all the governors, regardless of political and ideological affiliation” — the very institutions with which it is clearly impossible to carry out any serious public health measures, not to mention independent politics.

For its part, the Socialism and Liberty Party (PSOL)7Translator’s note: The Partido Socialismo e Liberdade (PSOL) is a broad “progressive” coalition in Brazil that includes a number of tendencies across the self-described “far left” of the political spectrum. published a resolution from its national executive leadership advocating “the departure of Jair Bolsonaro” and warning of the need “for the exit movement to occur in a democratic manner, built in a broad way and with popular support.” The manifesto, signed by the PSOL together with the PT and other parties, makes its orientation even clearer: practically, it is support for General Hamilton Mourão, the vice president, to take over the presidency (either because Bolsonaro gets impeached or resigns). This means renouncing not just a minimally independent path forward but even any democracy at all, instead just handing over the government to an ultrareactionary general who, on the anniversary of the military coup, praised Brazil’s 1964–85 dictatorial regime. In the short term, his policies aim to channel the legitimate rejection of Bolsonaro toward institutional solutions that strengthen institutional Bonapartism, as can be seen from the call made in his official note to “go along with the governors’ efforts” as part of a “broad unity” that includes even parties such as REDE, the Brazilian Sustainability Network Party — as long as they oppose Bolsonaro. A basic prerequisite for the PSOL to play any role in defending the people in this pandemic requires that it break with this policy of subjugation to Mourão, the governors, and institutional Bonapartism.

The best way to attack Bonapartism is with the most forceful response to the coronavirus, based on independent politics. Why don’t the PSOL members of Congress use the weight of their offices to demand immediate massive testing, the hiring of public health workers, and conversion of industry to produce medical and hospital supplies to serve the population? Fighting “the impending catastrophe” (to rescue from Lenin more than just the title of a pamphlet, as the MES current within the PSOL does)8Translator’s note: The Movimento Esquerda Socialista (MES, Socialist Left Movement) is one of several self-described Trotskyist current inside the PSOL. requires helping develop the self-activity of the workers, prioritizing measures that lead to the generalized workers’ control of all the economic and health initiatives governments put in place.

Workers’ Control and the Battle against the Pandemic

The most effective way to prevent Bolsonaro, the military, and the coup leaders of all stripes from continuing to unload the effects of the pandemic on the backs of the workers is to articulate an emergency program that will immediately allocate all the capitalists’ available resources to the fight against Covid-19.

There are almost unlimited resources. Just look at the billions that have been injected into the banks and companies. But the capitalists and their governments, responsible for the pitiful state of the health infrastructure, want to preserve their profits over our lives. That is why workers’ control of the production and distribution of medical and hospital supplies is a fundamental condition.

The Ministry of Health’s announcement that there have been 23 million tests is still a fiction. Doria’s policy of 2,000 tests per day, besides being insufficient, is a bunch of empty words. Even some of the tests already being done can take more than a week before the results come in. We demand massive testing — that is, that tests be administered for anyone showing symptoms and then, following the “route of the virus,” tests be done on anyone who has come in contact with those who are symptomatic. This should include anyone who asks to be tested on the grounds that they had contact with someone symptomatic but was not tested. In neighborhoods and regions where the infection rates re particularly high, massive random testing may be more advantageous. It must also include testing health workers and any other workers who have continued to work (there are many, including asymptomatic people) or return to work.

We must fight for what Bolsonaro and the governors refuse: centralizing the entire health system, including private health care (from large laboratories to hospital clinics and private hospitals), under the control of workers and specialists, to guarantee all the necessary facilities are available to take in those who become infected; confiscating all empty rooms in hotels and elsewhere; and providing masks (through emergency production, importation, etc.). It is urgent to hire all unemployed health workers and medical students who have already graduated to meet the needs of the population.

Neither Bolsonaro nor the governors want to touch the bosses’ profits. They are allowing them to continue to produce goods that are useless in the fight against the coronavirus while unprotected workers become infected. That must end. Industries that cannot produce goods useful to the population must be shut down, and all their workers who are sent home must receive their full wages, at the expense of the employers’ profits. The self-employed and workers in the informal sector must receive a monthly “quarantine salary” of 2,000 reals (about $375) for the duration of the crisis.

Working-class organizations must intervene in this crisis with a program independent of the different capitalist factions. The trade union confederations must abandon their passive adherence to institutional Bonapartism and wage a serious fight for these emergency measures. Only the health workers, trade unions, and popular organizations can be at the head of an emergency government — not all these coup leaders who care so little about our health and our jobs.

Such an emergency government would have, as one of its central tasks, to take whatever measures are necessary to protect the lives of millions. This would include calling and organizing a Free and Sovereign Constituent Assembly that would consolidate all legislative, executive, and judicial powers. In that assembly, a wholesale reconfiguration of the country could be democratically debated in order not only to respond to the immediate question of guaranteeing jobs and lives, but also to address the entire national structure that condemns the overwhelming majority of Brazilians to lives of misery.

That is the best way to channel the legitimate popular hatred of the government and to challenge Bolsonaro, the military, and all the coup leaders. In this struggle, Marxists will encourage the development of self-organizing bodies of the working class to expand workers’ control. That is the way forward to build an understanding of the need for a workers’ government to break with capitalism.

Published in Spanish on April 5 in Ideas de Izquierda.

Translation: Scott Cooper

Notes

| ↑1 | Translator’s note: iFood and Rappi are on-demand app-based delivery services. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Translator’s note: The Carteira Verde Amarela of November 11, 2019, formally Provisional Measure No. 905, was a deregulation of Brazil’s labor laws that allowed companies to create new precarious jobs — up to 20 percent of their workforce — for people ages 18 to 29. The employers were exempted from the payroll tax on these jobs, the tax that funds social security, and they were handed a 75 percent reduction in the mandatory savings they were otherwise supposed to put aside for workers as part of an unemployment compensation fund. It also essentially ended penalties on employers for firing workers. |

| ↑3 | Translator’s note: The term, from Karl Marx’s 1852 work The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, refers to an authoritarian leader who emerges when different sectors of social classes are struggling against each other and are unable to find a way to impose representatives from their own ranks. In this context, a “Bonaparte” emerges who presents himself as an arbiter from above, separate from the dominant class and somehow not beholden to any of its institutions. A Bonapartist leader often leans on the military and seeks to give the executive branch of government more autonomy from other branches. |

| ↑4 | Translator’s note: Operação Lava Jato (Operation Car Wash, because it was first uncovered at a car wash in Brasília) is an ongoing federal anticorruption investigation in Brazil launched in March 2014. First centered on money laundering, it was expanded to explore bribery allegations at the state oil company Petrobras, and then used to initiate an institutional coup through indictments and then imprisonment of a number of well-known politicians, including former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. Documents leaked to an investigative journalist in June 2019 reveal that a major motivation was to prevent Lula’s Workers Party from winning the 2018 presidential election that brought Bolsonaro to power. |

| ↑5 | Translator’s note: Marielle Franco, a city councilor in Rio de Janeiro from the Socialism and Liberty Party(PSOL) and strong critic of police brutality and the government’s extrajudicial killings, was gunned down on March 14, 2018, while being driven in a car after giving a speech. A year later, two former members of the military police were arrested and charged with her murder. They had ties to Carlos Bolsonaro, the president’s son, and had been photographed with the president. One was even his neighbor at a luxury apartment complex in Rio. |

| ↑6 | Translator’s note: The Central Única dos Trabalhadores (CUT, Unified Workers Central) is Brazil’s main national trade union confederation. The Central dos Trabalhadores e Trabalhadoras do Brasil (CTB, Central of Male and Female Workers of Brazil) is a confederation linked to the Communist Party of Brazil (PCdoB). |

| ↑7 | Translator’s note: The Partido Socialismo e Liberdade (PSOL) is a broad “progressive” coalition in Brazil that includes a number of tendencies across the self-described “far left” of the political spectrum. |

| ↑8 | Translator’s note: The Movimento Esquerda Socialista (MES, Socialist Left Movement) is one of several self-described Trotskyist current inside the PSOL. |