Photo: Reuters

The unexpected victory of Donald Trump has brought the discussion on racism and white supremacy back to center stage, with some arriving to the conclusion that the ‘white working class’ voted en bloc for Donald Trump and are thus to blame for his election. However, the situation is not so simple. Reproducing this false narrative without questioning the assumptions which underpin it only deepens–consciously or not—the divisions among workers and therefore undermines the chances of waging the fight against Trumpism and the bosses in general.

Did Trump win thanks to the vote of white workers? Trump could not have won if not for the support he received from, among others, millions of workers who were overwhelmingly white. These people voted for a racist bigot who slandered Mexicans, was consistently sexist and attacked Muslims repeatedly. We cannot be apologetic with those who voted for him, including the workers.

However, it is a mistake to think that the majority of white workers support Trump. From a categorical perspective “non-college educated white” does not equal “white worker,” a common flaw upon which mainstream media and exit polls base their figures. Many of these people without college degrees are small business owners i.e., middle class. One signal of the weight of middle class people among Trump voters is that they are on average wealthier than Clinton voters. He actually lost in a landslide among those earning less than 50k/year.This demographic constitutes well over half of the US population, although they make up only 36 percent of the vote.

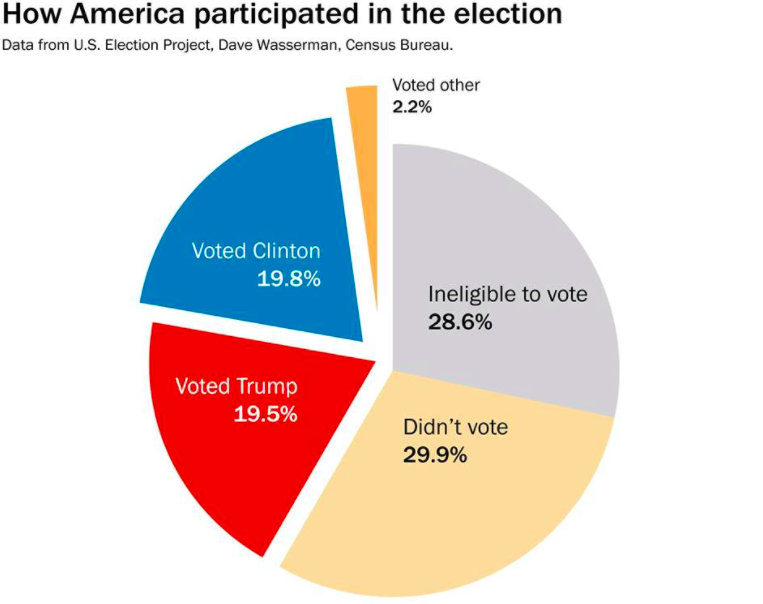

Even among eligible voters, only 19.5 percent voted for Trump. Sixty-nine percent of eligible voters are white and even among them, only 35 percent voted for Trump—65 percent of eligible white voters either cast their ballots for Hillary Clinton or a third candidate, or didn’t vote at all.

Source: Washington Post

Since most of the people who don’t vote are in the lower income brackets, it is safe to assume that support for Trump among white workers was even lower than the 35 percent of white eligible voters overall.

Thus, the majority of white workers did not vote for Donald Trump. This fact must be stressed because if the discussion centers around the logic that the majority of workers are Trump supporters, the situation becomes confused and we will make the wrong decisions. (The fact that millions voted for him is terrible news anyway.)

In fact, exit-polls show that Trump’s victory in the Rust Belt states of Ohio, Wisconsin, Michigan, Iowa and Pennsylvania was primarily the result of the fall in turnout of Democratic voters, particularly in key constituencies, rather than the growth of Republican vote. The widespread unpopularity of Hillary Clinton and the profound disappointment in Obama led many people of color to stay home. At the same time, this was influential in encouraging a sector of white voters who had previously voted Democrat to cross over to Trump.

Motivations

Despite all these caveats, the fact is that millions of workers voted for Trump. Now, the big question is, among those who voted for Trump, to what extent were they won over by the anti-establishment rhetoric or, by contrast, how much was the racist, xenophobic discourse that guided their vote?

Although it is impossible to have a certainty about this, some aspects are clear. Those who voted for Donald Trump either agreed with his racist discourse or tolerated it as a minor flaw, something that was not significant enough to withdraw their support. A sector did clearly more than tolerate his racist discourse. We have seen scores of racist, nationalist fanatics attend his rallies. The rise of the so called alt-right has a real presence beyond social networks, and some of that is reflected by the surge in hate crimes after Trump’s victory.

It is false to think that all Trump voters are white supremacist bigots. There is certainly some strata of impoverished workers or middle-class people who were seduced by the populist anti-establishment remarks and only tolerated his race bigotry. There are some reasons to believe this: the ostensible flight of votes from Barack Obama to Donald Trump, the extraordinary success of Trump in states where Bernie Sanders won the primaries, plus some anecdotal evidence here and there. Among those who declared that their economic conditions were worse than 4 years before, 78 percent voted for Trump and only 19 percent for Hillary.

This shows that at least part of the reasons to vote for Trump was other than racism. However, the political delimitation with Trump voters has to be clean-cut. Those who favored (mistaken) economic motivations over workers’ solidarity are headed in the wrong direction and represent an obstacle to achieving class unity. For this reason, it is a grave mistake to apologize for them, show sympathy or justify their vote. If there is to be resistance to Trump in government and the rise of the Right, we need class unity, and it begins with closing ranks across ethnicities, cultures, skin color, gender and sexuality.

Working Class, Ideology and Competition

The fragmentation of the working class along ethnic or racial lines is a tragedy. It undermines class power, weakens the labor movement and it stymies the fight against capitalism.

Racial prejudice among workers is real. There can be no perspective of uniting workers of all communities and ethnicities if we conceal or deny this. After recognizing it, the task is to identify and explain what are the forces that motivate it.

It is no secret that, in times of economic downturn, immigrant workers and racial minorities are useful scapegoats. Trump’s statements about Latinos and Muslims is a textbook example.

Nevertheless, did Trump just brainwash millions of people? The truth is that those racial sentiments are not only advanced by Trump and the Bourgeoisie in general—to “divide and conquer”. The notion of false consciousness is not enough to explain it. In other words, a theory of racism that portrays bosses as the only creators of culture and ideology, and workers as lemmings that are “programmed” to hate people of color, is not enough to understand reality.

Unfortunately, workers have actively embraced racism in various historical circumstances, and white workers have individually benefited from racial prejudice, even when these same divisions fatally wound the labor movement in the long run and ultimately hurt white workers themselves.

The Wrong Enemy, The Wrong Ally

In 1981, after the elections that gave Ronald Reagan the presidency, Johanna and Robert Brenner wrote an article in Against the Current that could be read today as if it were about Trump’s election.

Perplexed by the electoral results, they tried to make sense of the high level of support Reagan got among working class people. The Brenners begin the essay by recognizing the shift to the right, of which the widespread workers’ support for Reagan was a testimony. In the search for an explanation, they advance a powerful argument: in the face of an ebb in working-class organizing and action and after years (decades now) of defeats imposed on labor, workers are more likely to seek individual solutions to their plight than engage in a dubious struggle against an apparently “all-mighty boss”. After all, workers are “collective producers with a common interest (…) [but] they are also individual sellers of labor power in conflict with each other over jobs, promotions, etc.”

This constitutes a material basis for the divisions between workers of different communities, cultures or ethnicities. A privileged section of workers would then choose to defend its position at the expense of lower layers of the working class, “ally[ing] themselves, implicitly or explicitly, with the capitalist class, or a section of it.”

The Trap of Whiteness

From a more critical perspective, Noel Ignatiev advances a similar argument towards the end of his now famous How the Irish became white: “[T]he adherence of some workers to an alliance with capital on the basis of a shared ‘whiteness’ has been and is the greatest obstacle to the realization of [a working-class wide anticapitalist discourse].”

The book builds on a thorough historical research to show how Irish immigrants in America, subject to strong segregation in the United Kingdom and also, though to a lesser degree, in the US, advanced their position by isolating their struggle from that of African Americans. In those days, it was not even clear whether they should be considered “white”. Faced with the dichotomy of uniting with the Black “class brothers” to fight for an end to slavery and to all sorts of segregation or waging their own fight alone, they chose the latter. Their passport to citizenship went hand in hand with keeping Blacks in the ranks of the underclass. This is how they went from being forced to take the most menial and dangerous jobs to maintaining Blacks out of the shop floor by means of work stoppages whenever the boss hired a Black worker.

The Irish learned to segregate and despise Blacks in order to conquer and embrace their “whiteness.”

David Roediger tells the story of how Italian-Americans would feel their whiteness reasserted when going on raids to “beat up some niggers” in Harlem during World War 2. A participant of these Italian mobs remembered years later: “it was wonderful. It was new. The Italo-Americans stopped being Italo and start[ed] becoming American.” European immigrants as they arrived to America, generation after generation, bought into the lie of whiteness.

This brought about dire consequences. As James Baldwin pointed out, “because they think they are white they cannot allow themselves to be tormented by the suspicion that all men are brothers.” (…) “It is terrible paradox but those who believed that they could control and define black people divested themselves of the power to control and define themselves.”

Interracial Solidarity is Possible

On the other hand, a situation where Black, Brown and ‘white’ workers fight together shoulder by shoulder consolidates ties of solidarity among them and strengthens labor against capital. An example of these dynamics is featured in Brian Kelly’s Race, Class and Power in the Alabama Coalfields, 1909-1921. Against the backdrop of a segregated South, amid innumerable demonstrations of racism perpetrated by white workers against Blacks, the struggle of the miners in Birmingham, Alabama stands out as an example of interracial workers’ solidarity.

In 1920, 13,000 miners joined a strike called by the United Mine Workers (UMW) District 20 in Birmingham. The struggle escalated to armed resistance that could only be quelled by the deployment of military troops, dealing a long standing defeat to the UMW.

The degree and character of interracial collaboration in this episode of US history elicited a debate among labor historians–known as the Gutman-Hill debate—that has not yet been closed.

Brian Kelly recognizes the huge limitations of Black-white solidarity and the enduring racial prejudice among white workers, even in the case of the UMW’s strikes in Birmingham, 1908/1920. His work stands out, however, at providing evidence of the deliberate and relentless efforts on the part of the mine owners to pit workers against each other, to instill racial prejudice among them and to enhance the rivalry between Black and non-Black workers.

They hired exclusively Black scabs, they released a newspaper with anti-Black propaganda and false stories that painted Blacks as traitors or enemies, they forced the state government to issue anti-Black restrictions, etc. Under mounting pressure of the State governor and accusations of “racial subversion,” the UMW denied any attempt to equalize pay and conditions between Black and white workers. “[T]he main beneficiaries of and the principal force in maintaining Black oppression in the Birmingham district were its major steel, iron, and coal employers.”

Another—by no means less important—contribution of Kelly’s book is the fact that, although small, limited and fragile, interracial solidarity took place. With irreducible and undeniable remnants of anti-Black prejudice, miners fought the bosses shoulder by shoulder and build solidarity across race, despite the headwind of pervasive racism and legal segregation.

The two main takeaways of Kelly’s work are that (1) capital is a major force in maintaining, and no doubt the main beneficiaries of, the oppression of racial minorities; and (2) there is the potential for interracial joint struggles on the grounds of common material interests.

I would add to these the contention that stems from the UMW capitulation when they were race-baited by the government: in order to maintain a successful united front of workers against the bosses, and thus, in order to win, the demands of the most oppressed need to be advanced with no concessions by the whole of the working class.