Within 24 hours of Jair Bolsonaro becoming the president-elect of Brazil, 8 people were killed, including a baby that was shot by stray bullet at a rally. A Haddad supporter was killed in a campaign rally by a Bolsonaro supporter in the northern state of Ceará, where Haddad won with over 70% of the votes. In the month since the primary elections, over 50 people have experienced political violence at the hands of Bolsonaro supporters, with some people violently killed. This includes Mestre Moa, a capoeira instructor and anti-racist activist who was brutally murdered.

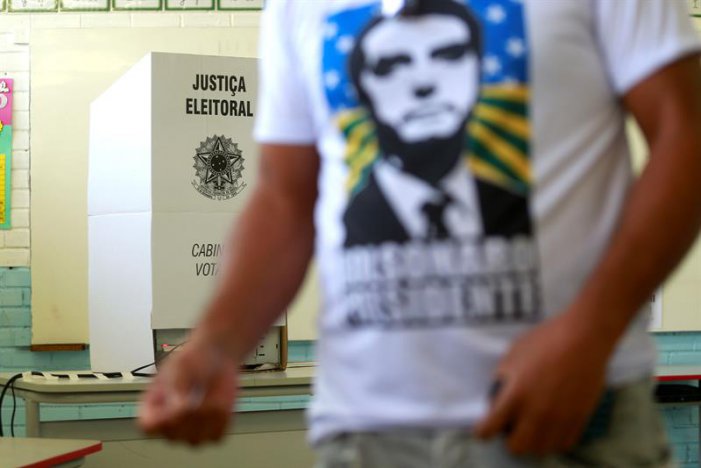

Last Sunday, Jair Bolsonaro was elected President of the world’s fourth-largest democracy. In the first round of the elections, the traditional parties performed abysmally. Especially the Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB), which in the last elections went to the runoffs against former President Dilma Rousseff, fell from 33% in 2014 to 4.77% this year.

The Workers’ Party (PT, Partido de Trabalhadores), which controlled the executive branch for much of the 21st century, was crushed in the first round, losing to Bolsonaro by 17 points. In the second round, the PT gained some ground but still lost by 10 points, giving Bolsonaro a decisive victory.

These elections were not only marked by violence but are also the most undemocratic elections since the end of the military dictatorship in 1985. Former President and front-runner, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva is currently serving a prison sentence for an arbitrary conviction. These elections are first and foremost an example of the ways that the Brazilian right will violate “democracy” in order to secure greater profits for the capitalists and more austerity for the working class.

Who is Bolsonaro?

Bolsonaro is a former military captain and long-time member of Congress who managed to brand himself as anti-corruption and anti-establishment with a brash and confrontational style of politics. He is perhaps most notorious for his comments against oppressed people: saying he would rather see his son dead than gay, that a woman colleague in Congress was too ugly to be raped, and, just last week, that leftists should be purged from the country. In the past, he proudly proclaimed that the military dictatorship should have killed more people, that he supports torture, and that, if elected president, he would shut down the Brazilian Congress. In the weeks after his first-round victory, he toned down the rhetoric– although it is hardly possible to forget his previous statements. (For more about Bolsonaro, read this article.)

Bolsonaro’s economic policies, which he has spoken very little about, can be summarized by the following statement by Paulo Guedes, the likely treasury secretary: “privatize everything.” Bolsonaro said that he hopes to privatize 50 out of 150 public companies in the first year of his Presidency. He plans to impose more austerity measures, meaning more cuts than are already in place under Michel Temer’s current right-wing administration.

It’s no wonder that many capitalists both in Brazil and in the U.S. side with Bolsonaro. Brazilian stocks soared in both the first-round victory of Bolsonaro, as well as in this second round. The Wall Street Journal endorsed Bolsonaro, and his win was applauded by Goldman Sachs. It is clear why U.S. corporations would be encouraged by Bolsonaro. There is Brazil’s largest company, the oil giant Petrobras, to finish privatizing. Other state companies set to be privatized are the post offices and banks. And there is the $270 billion dollars in interest payments to foreign banks, which is Bolsonaro is sure to continue to pay religiously. In this sense, unlike Trump’s nationalist “America First” rhetoric, Bolsonaro is characterized by a subservience to foreign capital, especially U.S. capital.

Trump and his cronies also applauded Bolsonaro. Trump tweeted: “Had a very good conversation with the newly elected President of Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro, who won his race by a substantial margin. We agreed that Brazil and the United States will work closely together on Trade, Military and everything else! Excellent call, wished him congrats!” John Bolton, Trump’s national security advisor called Bolsonaro “like minded” and a positive sign for Latin America, particularly in fighting what he called the “troika of tyranny”: Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua.

Bolsonaro has already announced that he will move the Brazilian embassy to Jerusalem and position Brazil against Venezuela’s Maduro. Bolsonaro and his supporters are notoriously xenophobic, attacking Venezuelan migrants into Brazil. Senior Bolsonaro officials have claimed they want a “regime change” in Venezuela, and one went even further, demanding a Brazilian and Colombian military intervention in Venezuela. This idea was quickly criticized as unconstitutional by his military advisors and future cabinet, as the Brazilian constitution bars foreign intervention without a UN vote.

A Global Trend?

Bolsonaro is just one of the many right-wing figures to emerge around the world, likely the most extreme. While we have not seen the emergence of fascism (yet), and the democratically elected Bolsonaro should be considered a right-wing Bonapartist (as explained in Bolsonarismo: Bonapartism or Fascism?), we have seen the rise of the extreme right-wing around world, even controlling the government in Hungary and Poland. In Germany, there have been mass mobilizations by the neo-Nazi far right.

Since the 2008 recession, global capital has struggled to fully recover and there is a massive economic crisis in Brazil. The 2008 recession catapulted the neoliberal project into crisis: the idea that history had “ended” and that capitalism could grow continually and with minimal crises, the idea that global agreements could secure profits for the world’s bourgeoisie (especially those of imperialist countries) and that nationalism was on the decline. This neoliberal project has crashed, first with Brexit and then with Trump’s “America First” protectionist policies. Trump doesn’t plan to leave the world stage, just renegotiate global agreements to impose better conditions for the U.S.

Although he is called the “Trump of the Tropics,” the fact that Brazil is a semi-colony subservient to imperialist interests makes Bolsonaro very much a neoliberal president. Privatizations and trade agreements with imperialism are likely to characterize his economic program.

Establishment parties all over the world have suffered from a crisis of legitimacy, as is evident in these Brazilian elections. Often conservatives have often the crisis of the establishment to their advantage– although not always. In Mexico, for example, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador expresses a more progressive outlet for an anti-establishment feeling. In the U.S., Bernie Sanders and more recently and to a lesser degree, Alexandria Ocasio Cortez have also expressed a rejection of the political establishment. However, these express a more progressive wing of capitalism; a mass socialist and revolutionary movement is yet to arise.

Brazil’s Most Undemocratic Elections

Bolsonaro will be Brazil’s 8th President since the end of the CIA backed military dictatorship in 1985. These elections were deeply undemocratic, marked by the imprisonment of the frontrunner, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva. Lula, as he is known in Brazil, was President of Brazil from 2003 to 2011, bringing the Workers Party (PT, or Partido de Trabalhadores) to the Presidency for the first time. The PT party was founded in the 1980’s by Lula, a union organizer, following massive waves of strikes by metal workers in São Paulo. They were political expression this massive working-class movement, and the CUT, Brazil’s largest union, was its labor expression. The PT continues to lead the CUT, a national trade union, and much of Brazil’s working class.

Lula was succeeded by Dilma Rousseff, who had been a guerrilla fighter against the military dictatorship. As the economic crisis hit, she began to implement increasingly harsh austerity measures. But they were not enough for Brazil’s capitalists and conservatives, who ousted her in an institutional coup d’etat. Her right-wing vice president, Michel Temer succeeded her, implementing massive austerity measures against the working class. The institutional coup was driven by many of the same right-wing forces that are behind Bolsonaro: the judicial branch, Brazil’s media monopoly Globo (which also supported Brazil’s military dictatorship), and Brazil’s largest landowners.

As the 2018 elections approached, it was clear that Lula was a favorite, likely to win over 50% of the votes in the first round. A few months ago, he was jailed on unproven corruption charges. This was a clear right-wing attack on the presidential favorite and had nothing to do with corruption. After all, many corrupt politicians, including President Temer himself, remain free. This institutional coup denied the Brazilian people the right to vote for their clear favorite in the elections.

Judge Sergio Moro was the primary orchestrator of the “Operation Car Wash”, which selectively prosecuted corrupt politicians, sending some to jail. He was the central player behind Dilma’s institutional coup, as well as Lula’s conviction. Some applauded him because he claimed to be fighting the corruption that is endemic in Brazilian politics. However, Moro, trained by the U.S. state department, attacked leaders of state-run corporations, implicitly making the case for more privatizations. Moro was not an unbiased judge seeking to eradicate corruption. He put Bolsonaro’s greatest electoral competitor in prison and will now be Attorney General in Bolsonaro’s administration.

The Failures of Compromise

In the face of these massive attacks, the PT has put forward an entirely impotent strategy of conciliating with the right and catering to the capitalists. The PT, born of labor strikes, refused to mobilize the working class against the institutional coup that ousted Dilma Rousseff, as well as against Lula’s imprisonment. This refusal paved the way for the rise of the right. Thousands gathered at the metal workers’ union with Lula before his arrest, and although some attempted to physically block the police from carrying out the arrest, he chose to turn himself in, claiming that he would prove his innocence through the justice system. Since then, he has not been allowed to make public addresses and was even barred from voting.

One year ago, there were two general strikes and hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets against the austerity measures. Instead of deepening this experience, organizing longer strikes with working-class committees, the PT diverted the movement into an electoral campaign for Lula. This meant canceling the nationwide general strike scheduled for June 30th, 2017 and allowing Temer’s labor reform law to pass without a struggle.

But the failures of the PT party did not begin there. A party of class conciliation from the beginning, the PT has done its best to guarantee capitalist profits. The economy boomed during Lula’s presidency, a time when, as he proudly proclaims, bankers profited like never before. While the economy performed well, the working class received the crumbs that resulted from a cycle of economic growth. But as the economy took a downward turn, austerity against the working class began. Workers and youth engaged in struggles against the PT and its cuts, such as in the massive youth demonstrations against bus fare hikes in 2013 and in the wave of labor strikes in 2015. These movements represented a progressive challenge to the PT, which questioned the austerity measures and cuts that Dilma had passed.

Furthermore, the PT invited the right into their administration! The powerful ultra-conservative evangelical caucus in Congress served as a key pillar of support for PT administrations. As such, it was able to veto any measures on abortion rights as well as on anti-homophobia measures. In addition, Michel Temer of the PMDB was Dilma’s chosen vice president. He went on to orchestrate the coup against Dilma and take the presidency.

Now What?

Some may read the situation in Brazil as a clear win for the right with little resistance. This would be incorrect. Only a week before the elections, hundreds of thousands of women took to the streets under the slogan #EleNao (Not Him). Thousands attended demonstrations against Bolsonaro, and there were university stoppages in protest. There is will to fight.

Furthermore, a vote for Bolsonaro does not necessarily mean a vote for his economic policies. A poll by DataPoder360 on October 18, 2018 indicated that only 37% of Bolsonaro supporters were in favor of privatizations and only 30% were in favor of privatizing Petrobras. Already Bolsonaro supporters have been active on twitter, repudiating his cabinet, which is expected to include notoriously corrupt members of Congress. In this sense, part of Bolsonaro’s working-class base may not be aware of the austerity measures that are about to rain down on them.

After Bolsonaro’s victory, there were large mobilizations in Sao Paulo, as well as in other states around the country. Universities organized student assemblies and forums to discuss and organize the resistance, demonstrating that Brazil will no passively accept the measure that Bolsonaro is likely to try to impose.

The PT and their electoral strategy of class conciliation has already demonstrated its clear impotence. Only a left that has no faith in the capitalist class, that seeks not to conciliate, but to crush the right, austerity, and capitalism can put up a real fight against Bolsonaro. This is true not only in Brazil but also in the U.S. and around the world.

As Diana Assunção, leader of the Movement of Revolutionary Workers says, “It is urgent to fight the right by organizing rank and file committees for struggle in each workplace and school… Only by rank and file organizing from the ground up will we be able to build a force capable of confronting the Bolsonaro and his allies in the military, the judiciary, and the media. We must use our hatred of Bolsonaro to fuel class struggle. It is the only way to defeat the radical right and force the capitalists to pay for their own crisis.”