Oscar winner Jordan Peele’s new film “Us” has cemented Peele as a mastermind of horror, with a record-breaking opening weekend and critical acclaim. The director of “Get Out” has a unique ability to mix political commentary with horror, asking the audience to think deeply about society while scaring the shit out of us. Placing Black actors front and center, Peele’s previous masterpiece, “Get Out”, is a brutal commentary on the myth of “postracial America,” bourgeois “liberalism” and police brutality.

There has been much public and critical discussion of “Us” as a political film. The film certainly positions itself as political but, because Peele adopts a more symbolic approach, the film’s politics are open to interpretation. This has led to praise by writers on both the mainstream liberal left and the far right. Breitbart News, a white supremacist organization, wrote what it considers a positive review, saying that the film warns against the “horrors of socialism.” Peele himself has said the film is “about a lot of things,” and while he wrote it with “a very clear meaning and commentary,” he also “wanted to design a film that was very personal for every individual.”

We, of course, disagree with Breitbart’s take. This is a leftist film that both leaves the audience scared and provokes questioning of the film and the society in which we live. While this is a piece of art, not political propaganda, it is still worthwhile to think through the messages in the film: What is it saying to the viewer? We’re going to assume that folks reading this have seen the film, so if you haven’t seen it, stop reading and go watch it!

Without a doubt, this film expresses some of the deep class and race contradictions of our society. The film portrays two groups of people: One above ground with all the happiness, depression and angst of life, when below ground live an artificially produced group of people called “the Tethered” who look exactly like those above ground and who each share a soul with one of them. We learn early in the film that while above ground, children play with toys and feast on delicious food, below ground the tethered cut their fingers on glass and are forced to eat raw rabbit, a grotesque mirror-image of the world above. The film is about “how the other half lives” and what happens when that other half rises up.

Peele sets up a metaphor of class conflict between the Tethered, who represent the oppressed underclass, and the humans on the surface, who represent the ruling class. There’s an artistic choice to first introduce us to not the oppressed class but to the ruling class. We are asked not to judge or resent them—indeed, the protagonists come off very well in the opening scenes of the film, and Peele uses very traditional screenwriting techniques to get us to sympathize with them: He introduces us to a loving family relaxing on vacation. When the oppressed class finally emerges wearing prison-like jumpsuits, we side with the original family and fear the others, actively rooting for their destruction. As the film goes on, however, and we learn more about the Tethered, we begin to feel more and more conflicted about supporting those aboveground.

Although the Tethered are first seen as grotesque, evil, mass murderers without language, heart or emotion, the film challenges the viewer throughout, making it difficult to “other” them. Each shares a soul with someone aboveground; they look exactly the same. Their prison garb reminds the viewer of the 2.2 million people locked up in the United States, the highest incarceration rate in the entire world. Like the Tethered, imprisoned folks are largely forgotten: beaten, abused, tortured via solidarity confinement, while others go about their day to day lives.

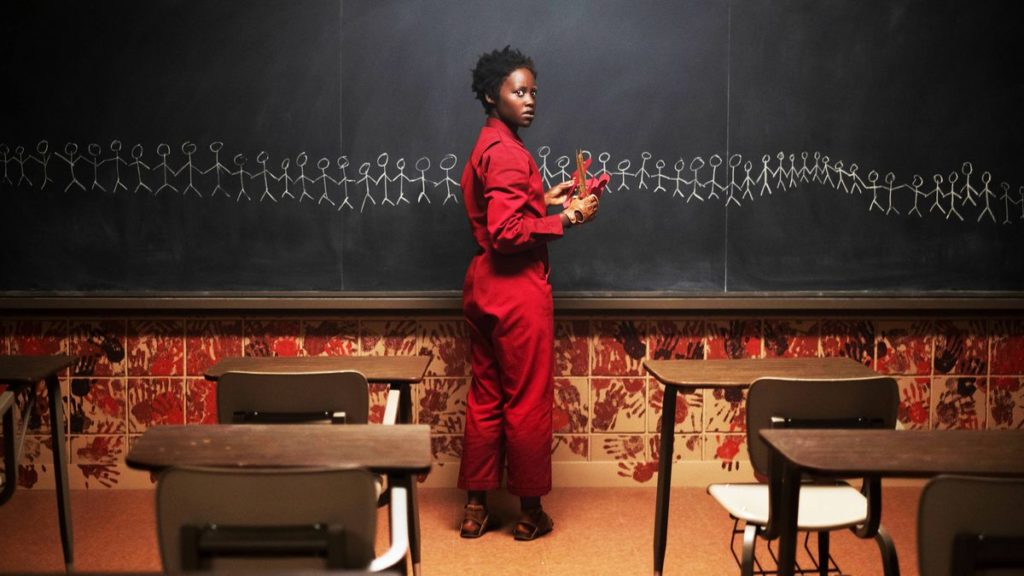

“We are Americans,” Red says when faced with Adelaide’s family. Red and Adelaide are brilliantly portrayed by Lupita Nyong’o, who challenges the viewer to viewer to see the Tethered as not only human, but American. The film isn’t talking about poor, third world misery; it is not talking about the undocumented immigrants that Trump calls a criminal menace. The film is talking about the misery at our doorstep, or underneath our feet, as it were. Even the title of the film, “Us,” can be read as “U.S.”

As the film develops, this point that the tethered are Americans, just like Adelaide, is taken up more strongly as it is revealed that Adelaide, the loving mother we have been rooting for throughout the film is actually a tethered. What’s more, the film hints at the possibility that Adelaide’s son may be a tethered, switched at another point before the start of the film. After all, instead of sand castles, he makes tunnels and other kids wonder why he is so strange: He hardly speaks, wears a strange mask and wanders away, close to the funhouse that is the entrance to the world of the tethered. Furthermore, his tethered has his mouth burned shut, making unclear if he can speak. In this sense, the film argues that the tethered are just Americans—who could be just like those above ground, given a different context.

The film pushes it further: Not only is Adelaide a Tethered, but she is a Tethered who did a horrible thing, kidnapping the actual Adelaide and thrusting her into the horrible conditions of the underground. So who is evil? Do those aboveground deserve their fate? As viewers, we can’t tell the difference, and this itself is a powerful statement: This is what happens when people are oppressed so badly for so long. There is nothing innately evil about them, but when the most oppressed of America rear their head, beware.

Whose Hands Across America?

The liberal American response to “how the other half lives,” to the poverty and misery of the most oppressed sectors is charity. Every natural disaster, every Christmas and Thanksgiving, there are politicians in photo ops providing food for the hungry or donating funds to the needy.

This film is a sharp critique of the farce of “charity,” with the Tethereds carrying out a gory parody of Hands Across America, which Adelaide sees on TV, as a child before being switched with a Tethered. The original Hands Across America, created in 1986, was an enormously well-funded charity project that resulted in 6.5 million people holding hands for 15 minutes in an attempt to form a chain across the entire United States. In order to get a space in this human chain, one had to donate at least $10 in order to fight hunger and homelessness. In the meantime, Ronald Reagan was president, cutting welfare using the racist tropes of the “welfare queen” and launching an offensive against labor unions, structural causes of hunger and homelessness. Reagan’s foreign policy was even more devastating, supporting right-wing leaders and coups around the world, instituting bloody anti-communist pro-U.S. regimes in countries such as Nicaragua and El Salvador. Clearly, holding hands for 15 minutes was a feel-good project, but it wouldn’t put a dent in the neoliberal offensive that began to take shape in the Reagan years.

Furthermore, although the charity raised $34 million, only 15 million was distributed to local nonprofits, to then distribute to the hungry and homeless. Those local nonprofits have their own operating costs, likely taking a cut of money as well. It’s hard to believe that much of the funds actually went to homeless people at all.

In the film, the Tethered unmask the ridiculous nature of Hands Across America, with Tethered killing their aboveground doppelgangers, forming a human chain across California. Joining bloody hands, responsible for murder, won’t help anyone or wipe away responsibility. Massive spectacles of solidarity seem absurd in the face of the murder committed.

In this sense, the film challenges the viewer: Isn’t it similarly absurd for Americans, whose government is responsible for bloody coups and is causing poverty and homelessness, to hold hands and act like that is atonement? Isn’t it similarly useless?

At the same time, in real life, do the people who wanted to end hunger and homelessness who held hands in the actual Hands Across America have blood on their hands? In the film, do the humans living aboveground have any responsibility in how those below ground live?

Class and “Us”

The tethered view those who live above ground as their enemy, as they live better than those below ground. This, however, is where the class metaphor seems to break down. In reality, there is not a one-to-one ratio of exploited and exploiters: As highlighted by the slogan of “99%” popularized by Occupy Wall Street, it is a small portion of people who concentrate massive amounts of wealth and power (although in reality, it’s more like the 70%). While the working class is immensely stratified, with some sectors of workers making a good living, especially in imperialist countries, it is nothing compared to the killing the capitalists make. And this sector of workers who make a decent living is diminishing rapidly with the attacks on unions characterized by the Reagan years and decades of neoliberalism.

We, the working class and oppressed, we who cannot enjoy the luxuries provided to the few, we who have few choices, are the overwhelming majority of society. And to go further, the capitalists are wealthy precisely because of the working class’s labor. It is the labor of the working class that produces the wealth for the capitalist class. And there are so few capitalists and so many of us.

The film, rather, presents us with a tension solely based on who lives in better conditions, not based on the causes of those better conditions. In fact, it argues that there is a fight to the death between the privileged and the oppressed, although the privileged don’t have any responsibility for the Tethered’s oppression.

“Us” and the State

In “Us” there is a horrible but absent villain: the creators of the Tethered. Those people who created this pseudo-class structure in which there are people below ground, unbeknownst to those aboveground. The state, the creators of the Tethered who created the oppressive system, are entirely absent from the film. We cannot be angry at something that isn’t there. And thus, he tethered do not seek their revenge on their creators but on their doppelgangers.

The viewer is presented with an impossible situation in the end: We sympathize with the Tethered and want them to be free. But we also can’t really condone the mass killing of those above ground who seemingly didn’t have any choice in having a horrible doppelganger of theirs being created. This choice exempts the state from its role in creating the tethered.

If we take the parallel into reality, it ignores the capitalist state, which creates and perpetuates the conditions in which we live. It ignores the direct and concrete profits of the capitalist class from the oppressed and exploited.

What Is to Be Done?

“Us” addresses both the inherent inequality and grotesque horror of class based society and the absurdity of liberal responses to it. Nothing but a complete overthrow can fix this. But the absence of the “real” enemies, the creators of the Tethered, made us leave the film feeling unsatisfied. In this sense, perhaps it is a commentary on our generation: We see so many problems. The gross inequalities of society have been unmasked and we are angry about it. Yet there isn’t clarity about the way forward. Who is the enemy? How can we fix it? What should be done? Much of our generation, like the film, isn’t sure.