In The Event of Literature (2012), you argue literary theory has been in decline for the last twenty years and that, historically, there has been a strong relationship between shifts in theory and social conflict. Does theory develop its highest point during periods of upheaval?

Literary theory reached its high point roughly when the political left was in ascendency. There was a major outbreak of such theory in the period from about 1965 to the mid or late 1970s, which coincides more or less with the time when the Left was a good deal more militant and self-confident than it is today. From the 1980s onward, with the tightening hold of advanced post-industrial capitalism, these theoretical outgrowths began to yield to postmodernism, which as Fredric Jameson has remarked is, among other things, the ideology of late capitalism.

Radical theory certainly didn’t fade away, but it was pushed to the margins, and gradually became less popular with students. The great exceptions to this were feminism, which continued to attract a good deal of interest, and post-colonialism, which became something of a growth industry and has continued to be so.

One shouldn’t conclude from this that theory is inherently radical. There are many non-radical forms of literary and cultural theory. But theory as such poses some fundamental questions–more fundamental than routine literary criticism. Whereas such criticism may ask, “What does the novel mean?,” theory asks, “What is a novel?”

Radical theory certainly didn’t fade away, but it was pushed to the margins, and gradually became less popular with students.

Theory is also a systematic reflection on the assumptions, procedures and conventions which govern a social or intellectual practice. It is, so to speak, the point at which that practice is forced into a new form of self-reflectiveness, taking itself as an object of its own inquiry. This doesn’t necessarily have subversive effects; but it may mean that the practice is forced to transform itself, having inspected some of its underlying assumptions in a newly critical way.

In The Ideology of the Aesthetic (1990), you argue the concept of literature is a recent phenomenon, one that emerged as a shelter for stable values in uncertain times. But you also point out that aesthetics has been a form of internalization of social values as well as a means of visualising utopias and questioning capitalist society. Does art still play this contradictory role in the present?

Both the concept of literature and the idea of the aesthetic are indeed politically double-edged. There are senses in which they conform to the ruling powers and other ways in which they challenge them–an ambiguity which is also true of many individual works of art. The concept of literature dates from a period when there was a felt need to protect certain creative and imaginative values from an increasingly philistine, mechanistic society. It’s more or less twinned at birth with the advent of industrial capitalism. This allowed such values to act as a powerful critique of that social order. But by the same token, it distanced them from everyday social life and sometimes offered an imaginary compensation for it. Which is to say that it behaved ideologically.

In advanced capitalist societies, where the very idea of the humanities is under threat, it’s vital to foster activities such as the study of art and culture precisely because they don’t have any immediate pragmatic purpose.

The aesthetic encountered a similar destiny. On the one hand, the so-called autonomy of the aesthetic artefact provided an image of self-determination and freedom in an autocratic society as well as challenging its abstract rationality by its sensory nature. In this sense it could be utopian. At the same time, however, that self-determination was among other things an image of the middle-class subject, obedient to no law but its own.

Of course these ambiguities remain with us today. In advanced capitalist societies, where the very idea of the humanities is under threat, it’s vital to foster activities such as the study of art and culture precisely because they don’t have any immediate pragmatic purpose. To this extent, they question the utilitarian, instrumentalist rationality of such regimes. This is why capitalism really has no time for them, and why even the universities now want to banish them.

On the other hand, socialist thought would not place art and culture as in the end, the most fundamental sites of struggle. Culture, in the everyday sense of the word, is the place where power sediments itself, beds itself down. Without this, it’s too harsh and abstract to win popular allegiance. Yet, postmodern culturalism is wrong to believe that culture is what’s basic in human affairs. Human beings are in the first place natural, material animals. They’re the kind of animals who need culture (in the broad sense of the term) if they are to survive; but that is because of their material nature as a species, what Marx calls their species-being.

In The Event of Literature, you develop the idea of the literary work as a “strategy”–a structure determined by its function as a special type of ‘response’ to questions posed by social reality. How can this definition of a literary work be reconciled with the “autonomy” of the work, as a self-governing phenomenon?

I don’t think there’s necessarily any contradiction between strategy and autonomy. A strategy can itself be autonomous, in the sense that it’s a distinctive piece of activity whose rules and procedures are peculiar and internal to it. The paradox of the work of art in this respect is that it does indeed work on something outside itself, namely problems in social reality, but that it does so ‘autonomously,’ in the sense of reprocessing or re-translating these problems into its own highly distinctive terms. In this sense, what begins as external or heteronomous to the work ends up as internal to it. A realist work must respect the heteronomous logic of its material (it can’t decide that New York is in the Arctic, as a modernist or postmodernist work might), but in doing so it simultaneously draws this fact into its own self-regulating structure.

You point out that postmodern and post-structuralist theories have ended in “anti-essentialist fundamentalism,” mirroring the very “fundamentalisms” they sought to undermine. Do postmodern definitions remain dominant in cultural and ideological discourse, or has the new situation of capitalist crisis and limited revival of class struggle given rise to new theories that are not theoretically or socially skeptical?

Postmodernism is supposed to be anti-foundational. But one might claim that it simply substitutes certain traditional foundations for a new one: culture. For postmodernism, culture is what you can’t dig beneath, because you would need to draw upon culture (concepts, methods and so on) in order to do so.

Since 9/11, we’ve witnessed the unfolding of a new and rather alarming grand narrative, at just the point when grand narratives were complacently said to be finished.

To this extent, one might claim that its anti-foundationalism is rather bogus. In any case, it all depends on what you mean by a foundation. Not all foundations need be metaphysical. There is, for example, the possibility of a pragmatic foundation, which one can find in the later Wittgenstein.

As to whether postmodern discourse is still dominant these days, I’d say it’s much less so. Since 9/11, we’ve witnessed the unfolding of a new and rather alarming grand narrative, at just the point when grand narratives were complacently said to be finished. One grand narrative–the Cold War–was indeed over, but, for reasons connected with the West’s victory in that struggle, it had no sooner ended than another got off the ground. Postmodernism, which had judged history to be now post-metaphysical, post-ideological, even post-historical, was thus caught off-guard. And I don’t believe it has ever really recovered.

You discuss the contributions and deficits of different literary theories developed in the 20th century. The Marxist perspective seems to have an important weight in your account. Is this tradition still as productive in the field of literary theory as it is in other areas?

The short answer to the question of whether there are any new Marxist critical contributions to literary theory is no. The historical context isn’t right for such developments. The work of Fredric Jameson, an individual who in my mind is the world’s most eminent critic, goes on. He comes up with one brilliant book after another in an era in which many other well-known critics have fallen silent.

Marxism is a lot more than a critical method. It’s a political practice, and if you have a major crisis of capitalism, it’s inevitable that it will still be in the air somewhere.

But there’s no new corpus of Marxist criticism. And given the unpropitious historical circumstances, one would scarcely expect there to be so. All the same, Marxism has most definitely not gone away, as post-structuralism (rather mysteriously) has, even perhaps postmodernism.

This is largely because Marxism is a lot more than a critical method. It’s a political practice, and if you have a major crisis of capitalism, it’s inevitable that it will still be in the air somewhere. The same is true of feminism, whose critical high point lies some decades behind us, but which has survived in modified form because the political issues it addresses are so vital. Theories come and go. What persists is injustice. And as long as that is the case, there will always be some kind of intellectual and artistic response to it.

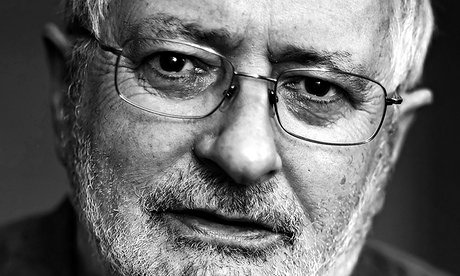

Interviewed by Alejandra Ríos