The coronavirus pandemic continues to progress and there are now 3 billion people quarantined throughout the world. In France, the threshold of 2,000 deaths has just been crossed and the “wave” has only just begun. However, many nonessential companies continue to operate and, in both essential and nonessential sectors, there is testimony from many employees about being forced to work without protection or satisfactory hygiene measures in place. Under these conditions, class struggle takes the form of a direct struggle for life. That is why workers’ control over production, working conditions, and safety measures is the only solution.

* * *

In “normal” times under capitalism, the entirety of production is designed so workers have no say in what is produced or how. The capitalist is in total command, aided by engineers, managers, and foremen. He exercises control over work processes through the planning office, which analyzes work and breaks it down into a multitude of tasks, some simpler than others. This is called the scientific organization of work, or rather the scientific organization of others’ work. The more “rational” a work organization, the more labor is depleted, fragmented, and deskilled, and the less control employees have over production. No matter the positions employees hold, whether in an office or on an assembly line, management dictates how they should perform their work.

The question of control over production in companies has become one of the major issues in the class struggle. The demand for workers’ control can take many different forms, from opening the books1Translator’s note: The demand to “open the books” has a long history in the revolutionary socialist movement. In the Transitional Program, Leon Trotsky writes of the needs to expose the secrets of capitalist exploitation and profit as part and parcel of workers’ control of industry. He explains that workers have a right to know: “Workers no less than capitalists have the right to know the ‘secrets’ of the factory, of the trust, of the whole branch of industry, of the national economy as a whole. First and foremost, banks, heavy industry and centralized transport should be placed under an observation glass.” He also explains that workers have a need to know: “The working out of even the most elementary economic plan — from the point of view of the exploited, not the exploiters — is impossible without workers’ control, that is, without the penetration of the workers’ eye into all open and concealed springs of capitalist economy.” to controlling the pace of work, but it basically translates into challenging the “usual” functioning and the legitimacy of the boss to make decisions. For example, at the end of the 19th century and during the 20th century in some domains, struggles over the control of production pitted tradesmen against bosses who sought to disregard worker qualifications. The worker’s “trade,” often acquired on the job, became an obstacle to the accumulation of capital. Likewise, during economic crises, control could take the form of workers’ management of companies that went bankrupt — a case in which control is a matter of economic survival for the workers. This same demand arises when the organization of work represents a danger to workers’ health.

In France, accidents at work were only recognized in the law only in 1898, while work-related illnesses were not included until 1919. Since then, employers have done everything they can to keep from acknowledging accidents or work-related illnesses because it increases the contributions they must make to health insurance. Documenting a work-related injury or illness is a real battle, as the case of asbestos-related illnesses has shown — employers try to falsify everything as they wait for the victims to die. Even today, there are still tens of thousands of French employees living with work-related diseases (more than 70,000, according to some estimates, some 85 percent of which are musculoskeletal disorders), and estimates are that 1,700 work-related cancers are diagnosed each year. Finally, occupational medicine, which is supposed to promote the recognition of work-related illnesses and accidents at work, has long played an ambiguous role when it comes to workers’ health. Either the doctors are in cahoots with the bosses, or the procedures for having a disease diagnosed take too long, are too complex, and are too bureaucratic to be of any use to employees. Clearly, health is too important to be left in the hands of the bosses.

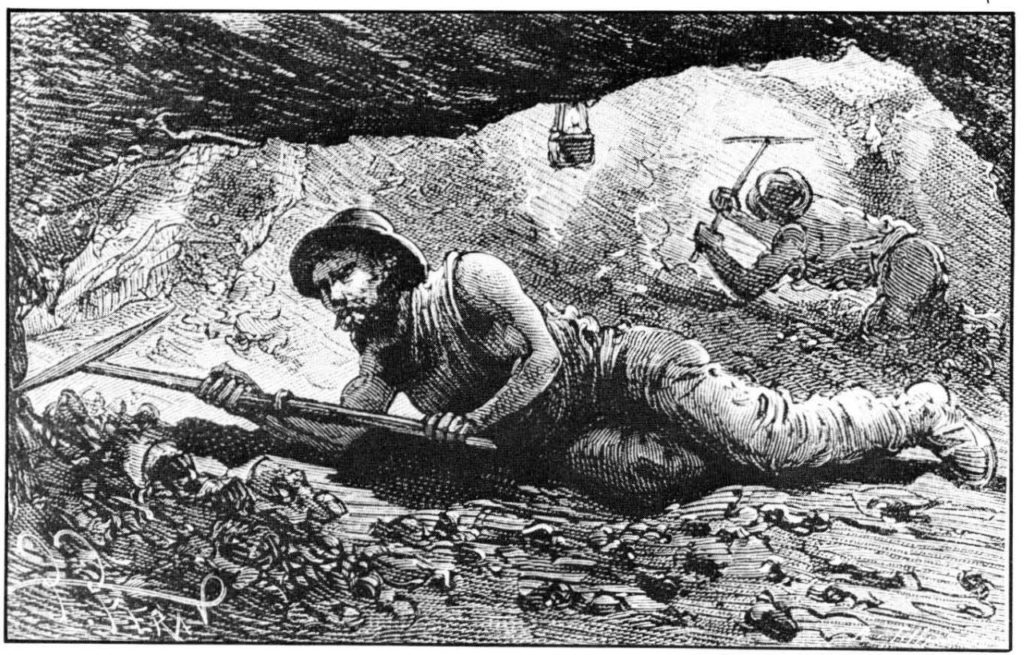

The Historical Example of the Miners’ Delegates

Historically in France, the demand for workers’ control over safety at work arose in connection with safety in the mines at the end of the 19th century. The experience of what were then known as “miners’ delegates” is little known to this day. Few sources exist and few studies have been done, but it seems particularly inspiring in the fight for the health and safety of workers in the context of the fight against the coronavirus.

Work in the mines was known to be particularly dangerous and had led to many fatal accidents. Accidents were frequent, and there were no protections under the law. Under those conditions, the miners established “miners’ delegates” whose role was to monitor safety preventively to limit accidents, but also to determine the causes and responsibility after accidents. These delegates were elected directly by the workers, from among their ranks, and acted as a real counter-power in the mines, since they challenged the authority of the boss over the organization and over safety in the workplace. Gradually, this function spread to the rest of the corporation.

Soon, recognition of these miners’ delegates became an issue. At a socialist workers’ congress in the east of France on June 6, 1881, former miner activist Michel Rondet issued a demand for the legal recognition of workers’ delegates for safety in the mines. The miners’ delegates demanded the right to accompany mine guards to accident scenes and to draw up joint reports. Until then, these reports were always largely skewed in favor of the companies, either because management found ways to corrupt the mine inspectors or because they simply lacked any practical knowledge. In 1882, the Saint-Étienne miners’ union association endorsed this idea, which was submitted in the form of a law to the National Assembly, supported by Jean Jaurès.2Translator’s note: Jaurès was a leading French social democrat. The National Federation of Miners then took it up in 1883.

The law of July 8, 1890, enacted with the support of the Socialists, finally recognized the role of the miners’ delegates. Their official function was to draw up reports of their visits underground, either after accidents or when they accompanied mine inspectors. However, their work was fraught with mishaps and obstacles. The bosses did everything possible to reduce the hours of the delegates, the frequency of their visits underground, and to prevent them from dealing with issues other than safety. Moreover, the institutionalization of the delegates’ work left them with less room to maneuver. They law spelled out that they were responsible only for examining the safety conditions of employees and, in the event of an accident, the conditions under which the accident would have occurred. Article 11 of the law even provided for the annulment of any miners’ delegate election in which a candidate expressed interest in a matter other than safety. Finally, there was the matter of who could be elected as a delegate. The law specified that one must be of French nationality, be over 25 years of age, and know how to read and write, which excluded about two-thirds of all miners. It also, however, stipulated that no member of management could be elected as a delegate, and that miners could elect someone who has been away from the mines for less than three years. That made it possible to elect miners who had been dismissed for trade unionism and to choose people who would not be submissive to employer authority, for example.

In a 1931 letter by Leon Trotsky on the subject of workers’ control, he reminds us that workers’ control of production leads to a form of “dual power” in the company and thus to a contradictory and confrontational situation. This has nothing to do with the class-collaboration of “participation” or “co-management,” to use more contemporary terms. In the case of the miners’ delegates, their struggle had led to their progressive institutionalization. Over the years, they became what we today call “employee delegates.”3Translator’s note: In France, délégués du personnel are roughly equivalent to shop stewards in unionized workplaces in the United States. They are elected as part of collective bargaining agreements and deal with worker grievances, ensure the Labor Code is applied appropriately, and depending on the size of the company may constitute committees on safety, working conditions, sanitation, and so on. Their disruptive potential to control safety and challenge the prerogatives of employers was stripped from them in favor of daily management of working conditions.

Covid-19 and the Fight for Control of Sanitary Measures

The example of the miners’ delegates, despite its limitations, shows it is possible to exercise control over working conditions in order to guarantee the safety of workers. Today, it could be said that the struggle to shut down nonessential enterprises and the struggle to control and guarantee satisfactory safety conditions for the sectors essential to the management of the crisis are two ways of posing the perspective of workers’ control.

The examples of aeronautics in the Toulouse region and of public transit in the Paris region show it is possible to fight concretely for this perspective. At Ateliers de la Haute-Garonne, an Airbus subcontractor, the CGT trade union is calling for the establishment of a committee to control health measures, completely independent of management, in the event of a return to work. This committee must be able to bring together elected staff members and any employee who volunteers. As for Paris-area public transit, this committee could also include riders, who are also exposed to the lack of hygiene measures on the RATP or SNCF buses and trains. As in 19th century mining, employers cannot be trusted to implement health and safety measures in companies.

Thus far, the trade union leaderships have failed to adopt such an orientation. The most treacherous are calling openly for a sacred union with MEDEF 4Translator’s note: The Mouvement des Entreprises de France, MEDEF, is France’s largest employer federation. and the government — the same that just passed ordinances making it possible to increase work to 60 hours per week and to force people back to work in order to bolster the economy. And even though he has positioned himself more to the left, CGT General Secretary Philippe Martinez has asked the government to draw up a list of activities “essential to the health and life of citizens.”

But it is impossible to trust the government of Emmanuel Macron to draw up such a list, as the trade unionists and combative militants opposing the return to work are demonstrating on the ground. That is why the CGT should break off discussions once and for all with this government, which has already decided to make us bear the burden of the coming economic crisis while at the same time rewarding employers. The example of Italy shows that the promises of European governments to close down nonessential companies cannot be believed. While the government of Giuseppe Conte promised to shut down nonessential activities, Cofindustria, the Italian MEDEF, pushed for sectors of “strategic importance for the economy” to be spared. Thus, the arms factories, aeronautics, textiles, and so on continued to operate … until a strike, with broad participation, took place on March 25, echoed by hundreds of nurses and healthcare workers who declared: “It’s time to go on strike. Health and safety first! Although our [participation] in the strike is only symbolic — one-minute rotations among on-call staff between 1:30 and 2:30 pm — we are asking you to strike. Strike for us, too.”

Rather than an “Italian-style” agreement, which is only a variant of the sacred union demanded by Macron, worker control over safety and production is our only way out of the health crisis.

First published on March 28 in French in Révolution Permanente Dimanche.

Translation: Scott Cooper

Notes

| ↑1 | Translator’s note: The demand to “open the books” has a long history in the revolutionary socialist movement. In the Transitional Program, Leon Trotsky writes of the needs to expose the secrets of capitalist exploitation and profit as part and parcel of workers’ control of industry. He explains that workers have a right to know: “Workers no less than capitalists have the right to know the ‘secrets’ of the factory, of the trust, of the whole branch of industry, of the national economy as a whole. First and foremost, banks, heavy industry and centralized transport should be placed under an observation glass.” He also explains that workers have a need to know: “The working out of even the most elementary economic plan — from the point of view of the exploited, not the exploiters — is impossible without workers’ control, that is, without the penetration of the workers’ eye into all open and concealed springs of capitalist economy.” |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Translator’s note: Jaurès was a leading French social democrat. |

| ↑3 | Translator’s note: In France, délégués du personnel are roughly equivalent to shop stewards in unionized workplaces in the United States. They are elected as part of collective bargaining agreements and deal with worker grievances, ensure the Labor Code is applied appropriately, and depending on the size of the company may constitute committees on safety, working conditions, sanitation, and so on. |

| ↑4 | Translator’s note: The Mouvement des Entreprises de France, MEDEF, is France’s largest employer federation. |