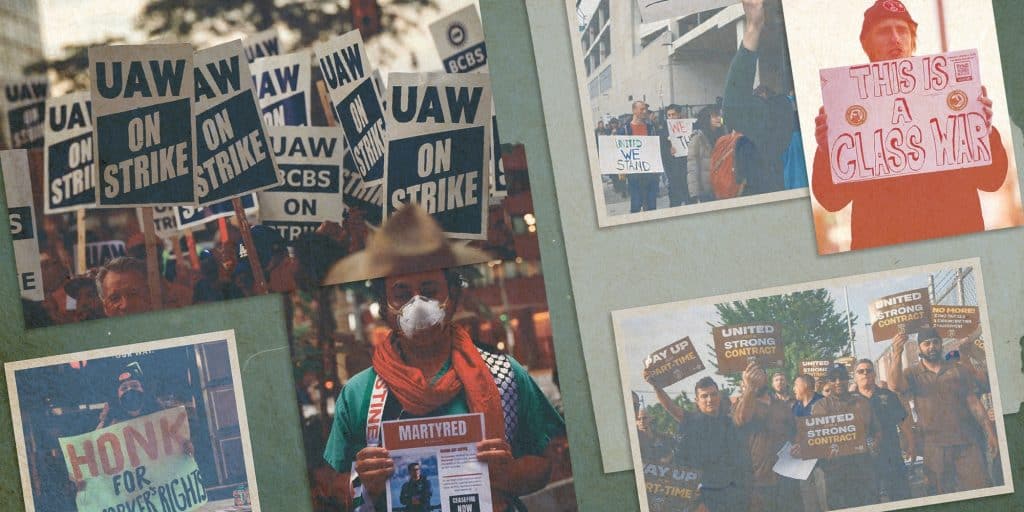

Over the last several years, labor activity in the U.S. has been on the rise. A new generation of workers who grew up in a post-2008 world converged with an older generation that never bowed to capitalists’ interests. In this piece, we analyze important aspects of labor activity, the emergence of a reformist union bureaucracy, and the significant rise in strike activity in light of deeper challenges of U.S. imperialism at home and abroad. Both the GOP and the Democrats are in a race to tighten their relationship with the working class, and neither has anything but the interests of American imperialism in mind. The labor movement is at a crossroads, and the path forward is laid by anti-imperialist, class-independent politics rooted in rank-and-file self-organization. Being that neither the GOP nor the Democrats defend the interests of the working class and the oppressed, activists across the country must join hands with the youth writ large and build a working-class party that fights for socialism.

***

The Labor Notes conference will bring together workers from around the country who want to build a fighting labor movement and who understand that our power as workers can change our lives and all of society. This year, for the second time in a row, the conference is sold out. A new generation of union activists, many of whom participated in strikes and unionization campaigns in the last few years, will descend on Chicago to discuss the way forward for a combative labor movement.

This comes at a moment when labor is at the center of national politics. After decades of retreat, attacks, and stagnation, the labor movement has increasingly jumped into the class struggle. Just last year, there were 470 work stoppages, a demonstration of workers’ increased readiness to withhold their labor power in order to achieve their demands. There is also increased support for unions generally, according to various polls. Workers are seeing unions not only as a tool to fight for economic demands, but also to put forward political fights. For instance, workers all over the country have fought for resolutions in our unions against the brutal genocide in Palestine. Over two hundred unions, locals, and caucuses have called for a ceasefire, from the new Starbucks Workers United to SEIU, from PSC CUNY to the AFT.

The working class is at the center of the 2024 elections. In a context of growing workers’ struggles, the decline of U.S. imperialism, and a crisis of hegemony within the United States, Republicans and Democrats are in a battle for the support of the working class. The Democrats want to use unions to rebuild their ties with workers. But both the Democrats and Republicans, despite their populist promises, will only further exploitation and oppression of the U.S. and global working class.

For this reason, the labor movement needs class-independent politics – politics that are not tethered to capitalist parties. Millions of workers in the U.S. have been displaying confidence in the strength of the working class. Deepening this trend requires untethering the working class from the Democratic Party and their electoral agenda. Those courageous activists who are committed to building a society without exploitation and oppression, and to fighting for decent living standards for all U.S. workers, must seek every single path toward showing the labor movement that the Democratic Party is not our ally, that we can organize politically independently of the GOP and Democrats. The two-party system relentlessly tries to narrow the political horizon of the working class and the oppressed. The challenge we face ahead is to deepen the trust in our own strength as a class with irreconcilable differences from those of the imperialist bourgeoisie, to find ways to make every worker an agent in deciding the way forward collectively, to tie the fight for justice in our workplaces and neighborhoods to the fight against imperialism here and abroad (as so many have started doing around Palestine), and organize from below the fight not only for better contracts but also against the Far Right.

The “America First” Battle for the Working Class

To think about building a fighting labor movement, we must understand the working class in a tumultuous national and international terrain. The 2008 economic crisis opened a period that saw declining rates of profit and set the context for a generalized crisis of neoliberalism: an economic, political, and social crisis that has expressed itself in multiple ways at different moments, including a political polarization to the left and to the right. In this context, all kinds of political shifts have taken place: Trumpism and Sanderism, BLM and January 6, as well as a new labor movement. This reshifting terrain is, of course, not exclusive to the U.S. We’ve witnessed political polarization throughout the world, with rejection of traditional political parties and far-right populism emerging in countries like Brazil, Argentina, India, France and Hungary. The far-right phenomena is not short-lived, as Trumpism is demonstrating.

Closely linked to this polarization is the steady decline in U.S. imperialist hegemony, as expressed in the withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021, increased tensions with Iran, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and a growing rift with Netenyahu’s government in Israel, despite the U.S. continuing to arm the latter to the teeth. Although the U.S. remains the world’s strongest economic and military force, China is also emerging as a global superpower, exporting capital to semi-colonial countries and playing a key role in the development of new technologies like electric vehicles, semiconductors, and AI.

In this context, the U.S. has the strategic goal of rebuilding its global imperialist dominance. Despite differences among Democrats and Republicans, the chauvinism represented by Trump’s slogan “America First” is in many aspects bipartisan. Bipartisan agreements include strong anti-China and anti-immigrant sentiments, which serve to build a base to support a new chapter for the global economy, especially in manufacturing. This new economic stage threatens to ratchet up the exploitation of workers in new U.S. manufacturing sectors. Attempts to restructure the terrain of U.S. labor towards manufacturing entail vastly curbing imports from and reliance on China, coupled with expanding manufacturing in the non-union South.

The U.S. has also increased ‘nearshoring’ in Mexico, a strategy that involves moving manufacturing and production operations closer by, to a country over which the U.S. has more control and power. The tightening of anti-immigrant measures and militarization of borders in the U.S. reflect these goals of maintaining a cheap and vulnerable labor force in Mexico and reinforcing U.S. economic and imperialist hegemony in the region.

This declining hegemony has led both Biden and Trump to engage in demagogic promises to the working class; both declare that a combination of anti-China protectionist policies, with promises to revitalize American manufacturing, will bring about good new jobs. A clear example of this was last year, when both candidates visited Detroit during the UAW strike, making Biden the first sitting president to speak at a picket line in decades. Trump’s demagogy is heavily rooted in xenophobia, placing the blame for U.S. workers’ struggles squarely on immigrants, China, and “very unfair” policies of foreign governments. But we have also witnessed Biden taking up more and more of these xenophobic policies in an effort to compete with Trump.

The Barren Marriage of Democrats and Labor

Biden and the Democrats are attempting to present themselves as the lesser evil to Trump and the extremist Right. But far from protecting us from the Right, the election of Biden hasn’t stopped Trump or the Far Right; Republicans took control of the House in the 2022 midterm elections, and Trump is currently polling neck-in-neck with Biden ahead of the November 2024 presidential elections. Furthermore, under Biden’s administration, countless new right-wing bills passed in states around the country under the initiative of far-right governors and legislatures, including draconian abortion bans, attacks on the rights of trans people, and the rollback of affirmative action. Many of these were upheld by the Supreme Court.

For decades, labor union leaders largely bought into the idea that Democrats offered the better option for working people. Unions contributed hundreds of millions to Democratic election campaigns and cemented strong relationships with party leaders. This arrangement did not result in anything good for the working class, but instead in what the late Mike Davis called the “barren marriage” of labor and the Democrats. The bipartisan onslaught on unions through neoliberalism made unionization rates drop and loosened the coils between the Democrats and the working class. The Democratic Party became the party of “progressive neoliberalism,” as Nancy Fraser explains: an alliance in which Wall Street and Silicon Valley rely on the “borrowed charisma” of social movements to get elected and to implement austerity policies. It was precisely this progressive neoliberalism that Trump voters rejected, giving way to right wing populism.

But neither the projects of Trump nor Biden’s “America First” populism have so far been able gain hegemony over the working class. As polls show, there is historic disapproval and distrust of both candidates. While Trump relies on his hardened base and the real economic struggles of working class people to build his base, Biden is relying on proxies, like union leaders, to rebuild a relationship with the working class in the midst of this crisis of hegemony. The goal is to revitalize the relationship between the working class and the Democratic Party to constrain worker actions. This tactic fosters stability and support for U.S. institutions and imperialism, revitalizing the relationship between the working class and the Democratic Party, at the expense of the working class.

A New Labor Movement

There have been seismic shifts in the consciousness of the working class since the 2008 economic crisis. Occupy Wall Street and the Bernie Sanders campaign (despite the latter’s commitment to re-legitimizing the Democratic Party) brought attention to the massive wealth disparities that only increased under neoliberalism. In the aftermath of Trump’s electoral victory, the DSA grew exponentially, and socialism became more popular than capitalism among young people.

In recent years, the working class has emerged as a significant actor in U.S. politics, undergoing ideological shifts and leading increased strike activity. From the 2018-2019 teacher’s strike wave to Striketober in 2021, and from being labeled as “essential workers” during the pandemic to the phenomenon of the “Great Resignation,” a new political generation — dubbed “Generation U” for its attraction to unions — has been reshaping the terrain for class struggle in the United States. Promisingly, there are unions rising to prominence in companies that have historically relied on worker precarity — new unions at Amazon and Starbucks are the most conspicuous examples. These fights have inspired workers across the labor movement. But they also highlight the obstacles that follow a successful unionization vote, transitioning into the initial contract negotiation phase. Corporations are making these early stages of unionization incredibly hard, in part to hamstring these important processes and scare off union attempts in other sectors and industries.

The Black Lives Matter movement was a profound moment in class struggle, with millions across the country and world mobilizing against anti-Black racism. In the streets, BLM challenged the enormous public investments in police, linking these to the massive diversion of funding and divestment from communities of color, healthcare, and education. A sector of the labor movement began to question unions’ representation of the police, as expressed by the campaign SEIU Drop the Cops. And some took labor action against police brutality, like the ILWU shutting down the port on Juneteenth. However, these examples were not generalized with widespread strikes for Black lives because the vast majority of union leaderships kept the BLM movement separate from workplace struggles.

But the legacy of BLM continues to affect the labor movement. As Carmin Maffea explained in From BLM to Generation U: How the Spirit of the Uprising Persists in Today’s Labor Movement, “Due in part to the ideological and political influence of BLM, Starbucks workers like Casey say, ‘You can’t be pro-LGBTQ, pro-Black Lives Matter, pro all these things and be anti-union.’”

This new generation of workers sees the organic connection between labor struggles and broader struggles against oppression. Young workers understand that any barrier between so-called “bread-and-butter” issues and questions of special oppression is an artificial one meant to weaken worker power. The new labor activists see the organic connection between workplace issues and issues of oppression. This is expressed in the countless statements for Palestinian coming out of unions and labor groups, as well as combative labor actions such as Google workers who staged a sit-in earlier this month against the company’s AI agreement with the Israeli government, for which they have faced severe repression and 28 workers were fired. At Labor Notes, this connection between exploitation and oppression is expressed in the numerous panels on immigrant workers, LGBTQ+ workers, the Starbucks Workers United Strike in defense of trans rights last June, and more. This new generation of workers is playing an important role in revitalizing the labor movement and uniting it with struggles in defense of historically oppressed people.

Union Density: A Battle Against Union Busting and Anti-Union Laws

While we are witnessing more and more workers beginning to unionize, it has not reversed the historic decline in unions. High turnover levels, intense labor precarity, and faster growth of non-union jobs have kept overall unionization rates from rising.

The Economic Policy Institute (EPI) reported that in 2023 there were approximately 16.2 million workers in the United States represented by unions, marking an increase of around 191,000 from the previous year. However, despite the growth in the number of union-represented workers, the overall percentage of unionized workers experienced a slight decline from 11.3 percent to 11.2 percent. This declining trend has persisted for over four decades.

In their annual report, the EPI revealed that the share of nonunion workers who want a union at their workplace exceeds significantly the share who actually have union representation. Survey data from 2017 show that “nearly half of nonunion workers (48%) would vote to unionize their workplace if they could.”

A Gallup poll about labor unions shows that in 2023, 67 percent of people in the United States supported unions, a slight decrease from the previous year’s 71 percent — a record high in the last 50 years. Other surveys by Gallup reveal that support for workers greatly outstrips support for corporations. For example, three in four Americans sided with the United Auto Workers in their recent negotiations with U.S. auto companies.

Unionizing in the U.S. remains particularly difficult, with anti-union laws creating many barriers. Unionization remains a multi-step, months-long process in which bosses are able to engage in virtually unfettered anti-union propaganda and intimidation.

At the same time, unions have refused to go on the offensive to unionize sectors that are not organized and reverse the downward slope of union density. Newly elected AFL-CIO President Liz Shuler pledged to organize one million workers. . . over the next decade, far from what’s needed to reverse the trend of declining union density. To do that, we need to build a combative labor movement that fights against all the union-busting tactics of corporations and the anti-union laws of the state.

As Kim Moody explains in On New Terrain, borrowing from historian Eric Hobsbawm, the labor upsurge is not merely a slowly rising slope. Rather, class struggle happens in leaps, where previously conservative and apolitical workers suddenly throw themselves into labor action and struggle. While we are clearly on an upward slope of labor action, the numbers of strikes are far below those of the 1930s and the 1970s. At this point, unionization rates have also not lept ahead. While we have witnessed explosions in the terrain of social movements, from Black Lives Matter and to some degree the movement for Palestine, this has not yet meant mass radical actions by the working class in the labor movement. While on one hand union leaderships have played a key role in keeping social movements and the labor movement divided, the Democratic Party has played a central role in co-opting and quelling these movements. Part of our task as socialist workers is to fight against any division between labor and social movements, as well as against the co-option of the Democratic Party, which only serves to quell independent radical action of the working class.

2023 Had the Most Strikes in the Last 20 Years

While we have not yet witnessed a mass strike wave, 2023 was the year with the highest number of large strikes in decades. The U.S. Labor Department reported a staggering figure of 458,900 workers participating in 33 strikes within workplaces with more than 1,000 workers — a big leap from the 14 major strikes just 20 years before.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) 2023 report

Yet the official count by the Labor Department falls short of capturing the full extent of labor unrest, as it only tracks stoppages involving 1,000 or more workers. A separate database from Cornell University’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations recorded 466 strikes in 2023.

High-profile strikes like those of SAG-AFTRA and the WGA, the Coalition of Kaiser Permanente Unions, the Los Angeles Unified School District, and the UAW Stand-Up Strike contributed significantly to the overall increase. The workers’ movement of 2023 showed us that strikes work, and that we have the power to throw a wrench into the massive profits that the bosses obtain from squeezing our last drops of sweat. The combativeness of this new sector can come to fruition and open countless opportunities for the working class.

A Test for the Rank and File & the New Union Leaderships

Two of the most important struggles of 2023 were centered around the UAW and Teamsters, both with new union leaders who replaced bureaucratic, corrupt, and stodgy leaderships of the past decades. The UAW led a strike that, for the first time, directly affected the Big Three automakers — Ford Motor Company, General Motors, and Stellantis (formerly Chrystler) – all at once, while the Teamsters’ negotiations with UPS averted a potential strike that could have been the largest and most impactful in decades.

A common theme in both contract negotiations was the fight for more time off and an end to grueling, long-hour shifts. Workers want to reclaim their lives and protect their health in factories, warehouses, and trucks. They demand that bosses prioritize workers’ lives over profits. To articulate these aspirations and channel them into support for union leaderships, the UAW even proposed a 32-hour workweek with 40-hour pay. A very powerful idea. While automation and AI pose threats in the hands of capitalists, the UAW campaign shows that workers can fight to leverage this technology to work less and enjoy more free time.

As a result of their strike, the UAW secured higher wages, ended most of the two-tier system, obtained cost-of-living adjustments (COLA), and advanced pathways toward unionizing battery and electric vehicle (EV) plants.

Meanwhile, although the Teamsters did not go on strike, the strike preparations created major pressure to win concessions. The Teamsters also achieved higher wages, eliminated the two-tier system for drivers, and began the process of installing more air conditioning in trucks, albeit at a slow pace and with insufficient numbers.

These high-profile strikes put the working class at the center of national politics. It couldn’t be any different, as they revealed to all those who still refused to see the vital role played by workers in the country. To offer an example, the Big Three automakers’ factories combined produce about 50 percent of the vehicles manufactured annually in the U.S., accounting for 1.5 percent of U.S. GDP.

However, both unions fell short in several key areas. Neither ended tiered labor, allowing significantly lower wages for new temporary and hired workers compared to their counterparts under the contract. This was especially painful for UPS workers, who accepted a contract that continued low wages for part time workers, without going on strike. The UAW also ultimately dropped their demand for a reduced workweek. Furthermore, combative as they were compared to the bleak years of neoliberalism, these strike efforts did not fully rely on the strength of the rank and file. There were almost no spaces for discussion and deliberation (UAW autoworkers did not even know when and if the factories where they worked would stop until Fain’s livestream on Facebook).

Naturally, there are significant challenges with contract fights of national magnitudes such as UPS and UAW, but national negotiating committees could have been organized by delegates voted by regional and local strike committees (counting on the support of the community). This is but an example: the current state of the labor movement in the U.S. deserves to break with traditional union practices, such as having but a small layer of unionists deciding the next steps of the movement and limiting the fight to periods of contract negotiations. For example, if a national coordination of UPS and UAW strikes had taken place, we would be in a much better position, having learned through mistakes what went wrong and what worked. Many more workers would have blossomed and developed into organic organizers, and it would have been a serious example to follow – and that would have been just the tip of the iceberg.

The Movement for Palestine and Labor Zionism

One of the most important struggles taken up by the labor movement this last six months is the fight against the genocide in Palestine, which puts the rank and file in direct confrontation with the Biden administration and with union leaderships. As we explained in The Movement for Palestine Needs Independent, Working-Class Politics, the U.S. has been “the primary backer of Israel, both militarily and ideologically, using universities, unions, schools, and the media to promote and support Zionism. But a new generation is breaking with all that to create a movement against genocide, against Israel, and, for many, against U.S. imperialism.”

In a clear expression of the changes in the working class, workers all over the country demanded that their unions speak out against the genocide funded by the administration of Joe Biden, or as he’s known by activists, “Genocide Joe.” Despite decades of labor backing Zionism, tying our unions to the state of Israel and to the Democratic Party’s policies, rank and file members have forced our unions to pass resolutions condemning the genocide in Gaza.

Thousands of workers attending the Labor Notes conference have been part of the movement in solidarity with Palestine, and while the assault on Gaza continues, many are carrying the questions of “how do we end the genocide?” This conference should take with all its strength an anti-Zionist and pro-Palestine stand, discussing and organizing concrete measures to be taken in that direction. Workers around the world have shown the way by refusing to load weapons onto ships and appealing to workers from other countries to do the same. Workers in the U.S. can and must play a strategic role in fighting the state of Israel.

Most union leaders have stood in the way of any action that goes beyond a resolution. They have refused to mobilize members to actions. They have refused to heed the calls of Palestinian labor unions, who are calling workers to stop arms shipments to Israel, as workers in Belgium and Italy did.

This is particularly acute for the UAW, who called for a ceasefire, but continued to produce and ship weapons to Israel. The UAW members also pushed for the creation of the Divestment and Just Transition working group to study UAW investments in Israel. UAW leaders must follow through on this directive from members — and end all investments in the apartheid state. Further, unions like the UAW must also take up the fight to end the production of weapons bound for Israel, following the example of the ILWU, which refused to unload Israeli ships in 2021.

As we explained in Uniting Workers for Palestine Is a Fight for the Future of Labor, “The labor movement is at a crossroads. As it becomes more combative — with increased strikes and the building of more unions — it must make a complete break with business unionism, imperialism, and the Democratic Party if it is to fight on the side of Palestine…Fighting labor imperialism means fighting all these pernicious elements in the labor movement.”

We Must Resist the Attempts to Align the Labor Movement with the Democratic Party

Once again, the discussion of lesser evil will be on the table. The Far Right has been gaining ground worldwide, from the ascent of the new right-wing libertarian president in Argentina, Javier Milei, to the rise of the Alternative for Germany in the heart of Europe. Here in the U.S., the Far Right has succeeded in pushing the Republican Party further to the extreme, leading attacks against LGBTQ+ rights, abortion rights, and other basic freedoms, accompanied by xenophobic rhetoric and policies toward immigrants. In this context, the 2024 presidential elections will be portrayed as the “the most important election of our lifetime” and Democrats will present themselves as the only party capable of defending “democracy.”

However, during the Obama administration and the current Biden presidency, it has become evident that not only has the Democratic Party been incapable and clearly unwilling to combat the Far Right, but the Far Righthas also grown in strength during these years. The Democrats’ consistent austerity policies and governing on behalf of big business drives sectors of workers into the arms of the Right, especially in lieu of a real left political option.

The battle against the Far Right, amid the declining hegemony of the United States and escalating geopolitical tensions, demands nothing less than class independence. The Democrats don’t fight the Right; they compromise and, in fact, align with the Right on countless political issues. And their failed promises drive ever more people to the arms of the Right. We must fight the Right by putting forward a viable political alternative – by demonstrating that the real enemies are the capitalist class, not Mexican or Chinese workers; by fighting for free public healthcare and education for all; and by uniting workers around the fight against oppression.

Some important theorists have pointed in the opposite direction. Jane McAlavey, one of the most important contemporary labor strategists, has the merit of calling for a combative labor movement — one that organizes a supermajority to strike and strikes to win big in each workplace. She sees the need for deep rank and file organizing. She also understands the strategic role of logistics workers, like those at UPS, and the need to organize across industries for the strongest possible strike. She puts forward a version of class struggle unionism. But, for McAlavey, class struggle unionism can and should make important allies within the Democratic Party that, with adequate pressure, can fight in the interests of the labor movement and ultimately “democratize” capitalism to make life better for the working class.

By subordinating the working class to the political leadership of an imperialist, racist, pro-business party, the potential of the working class remains highly constricted. Workers are told they can’t do more than organize for better conditions of exploitation and vote every few years on which candidate will run the country on behalf of the ruling class. As socialists, we believe that a working class that organizes for itself has the potential to run all of society, not just vote for the lesser of two evils, or exert “pressure” on candidates. McAlavey’s politics does not do justice to the increase of class struggle in the American labor movement of recent years and the incredible desire of workers to fight not only for better working conditions but also against all forms of oppression.

DSA and Jacobin, who will be presenting at Labor Notes and are playing a significant role in the burgeoning labor movement, also deliberately attempt to align the working class with the Democratic Party. They call the Democratic Party’s economic populism “Trump’s kryptonite” to convince progressives to win more working-class voters. This strategy reduces the power of the working class to “voters” — in the best cases “strike and vote” — but never making workers subjects of their own political destiny. In other words, they abandon the idea of breaking with the Democratic Party and the working class having its own party. And further, it exists within the confines of populist nationalism, providing an economistic approach to politics. The logical conclusion of these politics means propping up and rallying people behind people like John Fetterman, who refuse to question the U.S. imperialist project. While Jacobin has since criticized Fetterman’s virulent Zionism, Fetterman’s nationalist attempts to speak to the working class lead directly to his Zionism.

The framework presented by McAlavey and the DSA created the context for a Labor Notes conference that is platforming labor leaders who are currently working to tie the working class to the Democrats. Shawn Fain, the leader of the UAW, has engaged in the McAlavey framework of using union struggles to rebuild the Democratic Party. Despite endorsing a ceasefire resolution, he endorsed the candidacy of “Genocide Joe,” after leading a strike and attending Biden’s State of the Union address, in an attempt to tie the heroic fighting spirit of the UAW members to the Biden 2024 campaign. In an interview on CBS news, when asked about elections, Shawn Fain replied, “Joe Biden has a history of serving others, and serving the working class, and fighting for the working class, standing with the working class.” This directly contradicts the fact that Biden serves and is funded by billionaires, and defends U.S. imperialist interests.

Even more alarmingly, Democrat Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson will be at the opening main session at Labor Notes. Despite his “progressive” profile, Johnson’s 2024 spending plan would “increase the overall Chicago Police Department (CPD) budget to nearly $2 billion.” According to a report by the Police Brutality Center, the CPD “on average, kills about 26 times more Black people than white people every year.”

The activists gathering at Labor Notes are to a large extent the same people who have been protesting on the streets and organizing in their workplaces and campuses, demanding an end to the Israeli occupation and genocide in Palestine. These same people are sure to be mobilizing against the DNC in August — and are going to face severe repression by Chicago police under Brandon Johnson, who is not authorizing protest near the convention.

The imperialist policies of the Democratic Party and its conciliatory politics toward the Far Right are not separate from their relationship to the working class and the labor movement. Both serve the interests of the capitalist class — the bosses — keeping the working class and class struggle in check, at times with intense repression, and at other times with concessions to bring sectors of the working class back into the fold on their terms.

With this in mind, the auspicious new developments in the labor movement — which are driven by activists, who are ready to use the firepower of the working class to fight for better living conditions and against oppression, and to change this system — cannot afford to see the Democrats as “friends with contradictions” that are allies on some issues and enemies on others. The working class has to forge its own policy to win big and force the hand of the two ruling class parties.

A Working Class Party That Fights for Socialism

U.S. imperialism’s responses to the crisis of neoliberalism and the significant decay of its hegemony, exemplified by the emergence of China as a serious challenger, rely on further attacks on the working class and the oppressed. The labor movement in the U.S. must rely on its combative tradition of massive strikes, such as the railway strike of 1877; the Minneapolis, Toledo, and San Francisco strikers in the early 30s; the unwavering fight of Black people in defense of civil rights and better working conditions; the anti-imperialist struggle in the 60s and 70s; and the feminist movement that did not succumb to liberalism and stood within and by the working class. Examples abound, despite energetic efforts of the establishment to downplay the combative tradition of the multiethnic working class. We must build on such traditions and at the same time set our eyes on socialism, the only possible path to guarantee a life free of exploitation and oppression, and ensure a harmonic relationship with nature. It is not realistic to place hopes inside the Democratic Party, a cornerstone of the racist, imperialist bipartisan regime.

The working class needs its own political organization — a working class party that fights for socialism, a party that faces each and every struggle with the strategic goal of uniting the ranks of the working class, bringing to its corner the poor, oppressed and all who suffer under capitalism, a party that actively contributes to the defeat of the American bourgeoisie. We need a party that understands that as long as there is capitalism, there will be injustice: exploitation of workers, the destruction of the environment, imperialism, oppression, and brutality. We need a party that fights against this system, not with the impossible goal of democratizing a system based on private accumulation of profit, but to build a new socialist society democratically run by working class and oppressed people.

A system where one percent of the population controls 32 percent of the country’s wealth does not deserve to linger. The material conditions are in place for everyone to live in better conditions and work less. Collective human knowledge, expressed in machines and new technologies, must be freed from the obstacles imposed by the private ownership of the means of production and exchange. This is what is necessary to build a system that is not governed by the desire for profit but by the needs of the entire society and in the greatest possible harmony with nature.