In September 1923, German Communist Ruth Fischer visited Moscow, where she observed that the people were excited about the prospects of revolution in the west:

[Moscow was] plastered with slogans welcoming the German revolution. Banners and streamers were posted in the center of the city with such slogans as “Russian Youth, Learn German — the German October Is Approaching.” Pictures of Clara Zetkin, Rosa Luxemburg, and Karl Liebknecht were to be seen in every shop window. In all factories, meetings were called to discuss “How Can We Help the German Revolution?”1Ruth Fischer, Stalin and German Communism: A Study in the Origins of the State Party (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1948), 312.

It is not hard to imagine the reasons for this renewed hope. If the German proletariat took power, then this would end the isolation of the Soviet Union and quite possibly change the whole international situation.

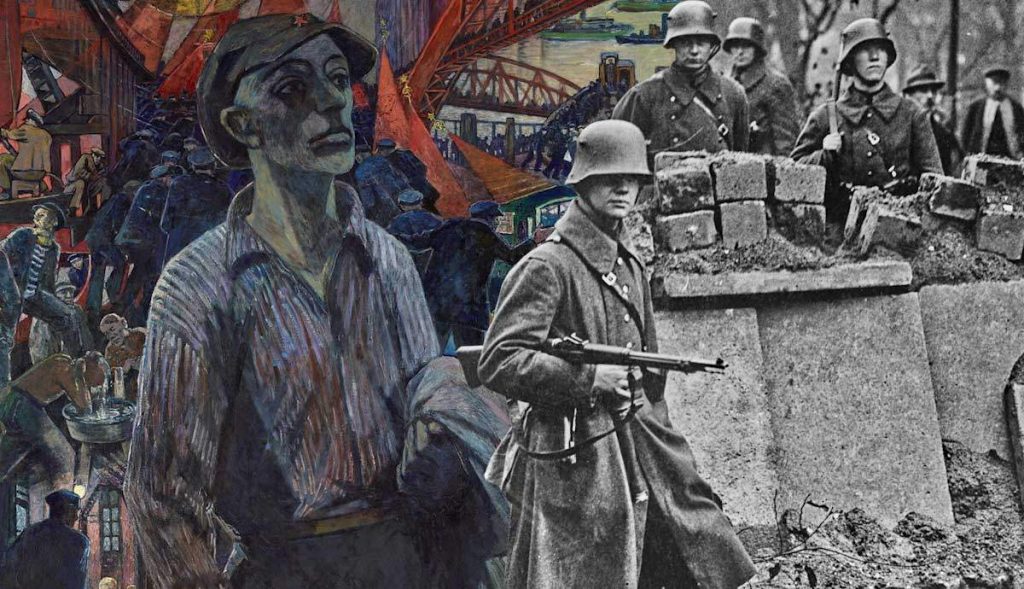

Looking back a century later, we can confidently say that a German Revolution would have changed the course of history. The spread of socialism to Germany — one of the most developed capitalist countries in the world — would have made Stalin’s slogan of “socialism in one country” a nonstarter. Furthermore, it would have meant that Adolf Hitler — should he have escaped justice from the German Red Guard — would have likely died unknown in exile. The German October of 1923 represents one of the moments when history failed to turn.

The Occupation of the Ruhr

The postwar years in Germany, from 1918 to 1921, were marked by the clash between the forces of revolution and counterrevolution. In Berlin, Munich, and the Ruhr, the working class rose in revolt, and a state of semi–civil war existed. But all these upheavals were violently suppressed thanks to the joint work of the German Social Democratic Party (SPD), the army, and right-wing paramilitary death squads known as the Freikorps.

Yet the Weimar Republic remained anything but stable. Under the terms of the Versailles Treaty (1919), which formally ended the First World War, Germany was obligated to not only accept responsibility for the war but also to pay reparations to the Allies (mainly France). Yet these reparations were more than Germany could afford to pay. Even with various reductions, the German debt remained enormous. Soon the economy suffered, and Germany fell behind on its payments.

To force Germany to pay reparations, French and Belgian troops occupied the industrial heartland of the Ruhr on January 11, 1923. Two days later, the conservative German government of Wilhelm Cuno called for passive resistance. As a result, local authorities and businesses in the Ruhr boycotted the occupation forces, industrial production ceased, and reparation payments were halted.

Passive resistance quickly led to the effective collapse of the German economy. This was most dramatically reflected in the collapse of the German mark. The exchange rate of the mark to the U.S. dollar in 1923 showed just how worthless it became:

January: 17,920

February: 20,000

May: 48,000

June: 110,000

July: 353,412

August: 4,620,455

September: 98,860,000

October: 25,260,208,000

November: 4,200,000,000,0002Werner T. Angress, Stillborn Revolution: The Communist Bid for Power in Germany, 1921–1923 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1963), 285, 350.

Scenes of hyperinflation became one of the enduring memories of 1923. The value of paper money disappeared so quickly that some companies paid their employees in the morning so they could rush and spend their wages at lunchtime. At restaurants, one could order a coffee and then find that the price had doubled or more by the time the bill arrived. The most familiar image of hyperinflation was of workers who brought wheelbarrows full of bank notes to grocery stores to buy bread and other simple items.

While the working class was reduced to pauperism and despair, the bourgeoisie used hyperinflation as an opportunity to gain immense fortunes and pay off their debts. As the historian Pierre Broué recounts,

It is said that Stinnes acquired 1,300 firms in the most varied sectors of activity, and that he confessed that he could not give a full account of his own affairs. The export industries made fabulous profits. On the one hand, the low level of rents and wages, and the fall in the real value of their debts, enabled them to charge prices against which no one could compete, and, on the other, they were paid in foreign exchange. Large businesses could deposit capital abroad in foreign currencies. They set up firms in Switzerland, the Netherlands and South America to hide their gains, and created intermediary companies through nominees to enable them to evade the law against capital exports. In short, the big capitalists collected their profits in dollars or gold, and paid their debts in paper — to their very great benefit.3Pierre Broué, The German Revolution 1917–1923 (Boston: Brill, 2005), 712.

Nor was passive resistance a common struggle by Germans of all classes. During the duration, the industrialists did not lose sight of their short-term interests. They made sure coal was not distributed to the workers who were on strike, particularly if they were left-wing activists. In addition, the Cuno government subsidized coal and steel businesses to compensate for their losses. The working class received no such relief. Not only was there a sharp divide between how the proletariat and bourgeoisie experienced hyperinflation, but the state seemed both powerless and unwilling to do anything about it.

Passive resistance also heightened social tensions in Germany. By February, the conflict in the Ruhr escalated into clashes with French soldiers, ending in violent reprisals. Moreover, the Far Right gained immeasurably from the crisis. Thanks to the complicity of the army, paramilitaries across Germany gained new volunteers, particularly Hitler’s National Socialists in Bavaria.

In this situation, the traditional reformist working-class organizations associated with the Social Democratic Party were completely powerless. As Broué notes,

The traditional trade-union practice of Social Democracy was empty of all content. Trade unionism was powerless, and collective agreements a joke. Working people left the unions, and often turned their anger against them, reproaching them for their passivity, and sometimes for their complicity in their plight. The collapse of the apparatuses of the trade unions and Social Democracy paralleled that of the state: what happened to notions of property, order and legality? How, in such an abyss, could anyone justify an attachment to parliamentary institutions, to the right to vote and universal suffrage? Neither the police nor the army escaped the infection. A whole world was dying. All the elements which only a year before had served as a basis for analysing German society had now been destroyed.4Broué, German Revolution, 714.

Germany appeared to meet the three criteria for Lenin’s definition of a revolutionary crisis: (1) the bourgeoisie could no longer rule in the old ways; (2) the suffering and exploitation of the oppressed classes had grown more acute; and (3) there was a considerable increase in the activity of the masses, who were now being drawn into political action.5V. I. Lenin, “Collapse of the Second International” (1915), Marxists Internet Archive. In this atmosphere, millions of Germans concluded that revolution offered the only escape.

The Communist Party of Germany

While all the objective factors of the revolution were falling into place, this was only part of the equation. For this situation to become a full-blown revolution, an organized vanguard party also had to exist, one that was willing to act and seize power. The dominant force on the Far Left was the Communist Party of Germany (KPD), which had been formed in late 1918. The KPD had participated in two abortive uprisings (1919 and 1921) and was allied with neighboring Soviet Russia. By 1922, the KPD numbered 222,000 members, making it the largest nonruling Communist Party in the world. Everyone on the Left and Right knew that the KPD stood for armed revolution and communism.

Despite its mass base and rich revolutionary experience, the KPD lacked a political leadership of the caliber of Lenin and Trotsky. Its early and talented leaders — Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht, and Eugen Leviné — had all been murdered during the revolutionary storms of 1919. The KPD’s next leader, Paul Levi, had been expelled after publicly criticizing the ultra-left March Action of 1921. Heinrich Brandler, August Thalheimer, Jacob Walcher, and Ernest Meyer formed the leadership of the KPD in 1923. Compared to their predecessors, however, they were politically cautious and dependent on Moscow for advice. After the March Action, according to Broué, that they had become

resolute “rightists,” systematically persisting in an attitude of prudence, armed with precautions against the putschist temptation or even a simple leftist reflex. Convinced by the leadership of the International of the magnitude of their blunder, they lost confidence in their own ability to think, and often failed to defend their viewpoint, so that they systematically accepted that of the Bolsheviks, who had at least been able to win their revolutionary struggle.6Broué, German Revolution, 577.

As a result, during the first half of 1923, the KPD’s line lacked direction, cohesion, and courage.

Even though the KPD possessed no clear revolutionary line, it was still a visible pole of attraction for the workers. Throughout the year, the party condemned the government and economic misery. It also led strikes and other actions to combat the crisis. In 1923, at least 70,000 joined the KPD, increasing its membership by a third. These numbers, however, underestimate the party’s reach in the working class. By June, the Communist Party had influence over at least 2,400,000 union members, approximately one third of the organized working class.7Chris Harman, The Lost Revolution: Germany 1918 to 1923 (London: Bookmarks, 1982), 246.

In addition, the KPD had a great deal of support among the factory council movement, which had taken over many functions from the unions. Out of about 20,000 factory councils, the Communists had a majority in 2,000. The Communists gained a hearing in the councils because they suggested forms of action that could succeed. Communist-led councils also organized committees to control prices on food and rent. The control committees allowed the KPD to mobilize not only workers but also women and the unemployed.

As the historian Arthur Rosenberg observed, both the state and Social Democracy were paralyzed by the crisis, while the KPD appeared to have a mandate for revolution by the middle of 1923:

Since the SPD failed to find a way out of the existing misery, the disappointment of the workers in the Cuno government was to some extent transferred to Social Democracy. The SPD was obliged to pay in 1923 for mistakes in policy of which they were entirely innocent, merely because their legal tactics seemed to imply acquiescence in the laws and therefore in the existing state of affairs. The KPD had no revolutionary policy either, but at least it criticised the Cuno government loudly and sharply and pointed to the example of Russia. Hence the masses flocked to it. As late as the end of 1922 the newly-united Social Democrat Party comprised the great majority of the German workers. During the next half-year conditions were completely changed. In the summer of 1923 the KPD undoubtedly had the majority of the German proletariat behind it.8Arthur Rosenberg, “The Occupation of the Ruhr and the Inflation, 1923,” chap. 7 in A History of the German Republic (1936), Marxists Internet Archive.

Between Internationalism and Nationalism

The Ruhr occupation had unleashed a wave of nationalism across Germany that the KPD attempted to navigate. One method it used to combat national chauvinism was to encourage fraternization between working-class Germans and French troops in the Ruhr. The KPD was assisted in this endeavor by the Communist Party of France (PCF) and the Communist International. Both the KPD and PCF produced posters encouraging French soldiers to resist the occupation. One bilingual poster read: “French soldiers, workers in uniform, you have been brought to the Rhine on the orders of your exploiters in order to put a yoke on your proletarian German brothers, already oppressed by their own bourgeoisie. French soldiers, your place is alongside the German workers. Fraternise with the German proletariat.”9Harman, Lost Revolution, 251. While the results of the fraternization policy were mixed, this was a principled action of internationalist agitation by the Comintern.

The Communists, however, also appealed to some of the nationalist sentiment in Germany. On May 28, the KPD paper Die Rote Fahne published a statement entitled “Down with the Government of National Disgrace and Treason against the People!” The Communists also attempted to win over outright fascist elements among the middle classes. Brandler argued that there was a class division in the fascist camp “between capitalist-paid Pinkerton” and “those petty bourgeois who have joined the [Fascist] movement from genuine nationalist disappointment.”10Angress, Stillborn Revolution, 318–19.

The main impetus for this nationalist line came from Karl Radek, who was partly responsible for the ultra-leftism of the March Action in 1921. Now he argued that the Versailles Treaty was reducing Germany to the rank of a colony, which meant that the Communists must “place the nation first.” At an enlarged meeting of the Comintern’s Executive Committee, held in June 1923, Radek made a speech eulogizing Leo Schlageter, who had been executed by the French in the Ruhr. A martyr to the nationalists, Schlageter was a Freikorps veteran who fought the Bolsheviks in the Baltics and the workers in the Ruhr in 1920. Radek claimed that Schlageter was an honorable, albeit misguided, figure who deserved to be honored by the Communists. He argued that the example of Schlageter showed that Communists should join together with rank-and-file nationalists:

But we believe that the great majority of the nationalist-minded masses belong not to the camp of the capitalists but to the camp of the workers. We want to find, and we shall find, the path to these masses. We shall do all in our power to make men like Schlageter, who are prepared to go to their deaths for a common cause, not wanderers into the void, but wanderers into a better future for the whole of mankind; that they should not spill their hot, unselfish blood for the profit of the coal and iron barons, but in the cause of the great toiling German people, which is a member of the family of peoples fighting for their emancipation.11Karl Radek, “Leo Schlageter: The Wanderer into the Void” (June 1923), Marxists Internet Archive. In 1933, the philosopher and Nazi Party member Martin Heidegger also praised Schlageter as an authentic hero for Germany: “Schlageter died the most difficult of all deaths. Not in the front line as the leader of his field artillery battery, not in the tumult of an attack, and not in a grim defensive action—no, he stood defenseless before the French rifles. But he stood and bore the most difficult thing a man can bear. Yet even this could have been borne with a final rush of jubilation, had a victory been won and the greatest of the awakening nation shone forth.” Martin Heidegger, “Schlageter (May 26, 1933),” in Richard Wolin, ed., The Heidegger Controversy: A Critical Reader (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993), 42.

The KPD’s embrace of the “Schlageter line” was endorsed by Comintern president Grigorii Zinoviev. This began a Communist campaign of appeals to German nationalists, including joint public meetings and debates with the Nazis. However, Communist speakers seemed more inclined to appeal to the anti-Semitic prejudices of their audience than to combat them. For example, KPD leader Ruth Fischer said at one meeting, “Whoever cries out against Jewish capital … is already a fighter for his class [Klassenkämpfer], even though he may not know it. You are against the stock market jobbers. Fine. Trample the Jewish capitalists down, hang them from the lampposts. … But … how do you feel about the big capitalists, the Stinnes, Klöckner? Only in alliance with Russia, Gentlemen of the völkische side, can the German people expel French capitalism from the Ruhr region.”12Angress, Stillborn Revolution, 339–40. Years later, Fischer defended her remarks as follows: “At a meeting of Berlin University students organized by the Berlin party branch, I was the speaker. The attitude of the nationalists against capitalism was discussed, and I was obliged to answer some anti-Semitic remarks. I said that Communism was for fighting Jewish capitalists only if all capitalists, Jewish and Gentile, were the object of the same attack. This episode has been cited and distorted over and over again in publications on German Communism”; Fischer, Stalin and German Communism, 283.

These “debates” continued until August 14, when the Nazis broke them off. Some historians, such as Broué and Harman, claim that the debates ended because the Communists were making headway among Nazi supporters. Yet a more sober analysis reveals that the Schlageter line brought little to no political benefit to the Communists. Radek claimed that his purpose had been to combat fascism by showing the petty bourgeoisie that capitalism was the source of their legitimate nationalist grievances. But this adaptation to the Right brought with it the genuine danger that sections of the proletarian movement could cross over to the class enemy. In addition, the campaign undercut initiatives for fraternization with French soldiers and building a united front with the SPD.

However wrongheaded the Schlageter line was, it was marginal compared to the KPD’s calls for a united front with the SPD against the Nazis. Furthermore, the KPD’s main effort in 1923 was against nationalism. For example, Communist deputies in the Reichstag voted against nationalist resolutions, while the Social Democrats voted for them.

Toward Insurrection

Throughout the spring and summer of 1923, the situation in Germany continued to deteriorate. Wages lost all their value, and the populace headed toward destitution. The working class found itself desperately fighting for the bare necessities as bread riots erupted in major cities. As Fischer observed, the state seemed to be fracturing under the strain of the crisis:

This disruption of economic life endangered the legal structure of the Weimar Republic. Civil servants lost their ties to the state; their small salaries had no relation to their daily needs; they felt themselves in a boat without a rudder. Police troops, in sympathy with the rioting populace, lost their combative spirit against the hunger demonstrations and closed their eyes to the sabotage groups and clandestine military formations mushrooming throughout the Reich. Hamburg was so tense that the police did not dare interfere with looting of foodstuffs by the hungry masses. In August, large demonstrations of dock workers in the Hamburg harbor led to rioting. “Parts of the police,” [KPD member Walter] Zeutschel wrote, “are regarded as unreliable; they sympathize with the working class.” The Cuno cabinet itself contributed to the weakening of legality by sponsoring the Black Reichswehr and instigating sabotage in the Ruhr.13Fischer, Stalin and German Communism, 291–92.

In June and July, a strike wave engulfed Germany. By now, the KPD wanted to show that it could lead a nationwide movement. To that end, Brandler proposed an Anti-fascist Day for July 29. This was not just a call for a united front against the Right, but also a chance for the Communists to show their strength. Brandler’s plan was adopted by the KPD, and he wrote a front-page article announcing it in Die Rote Fahne:

We Communists can win this battle with the counter-revolution only if we succeed in leading the Social-Democratic and non-party workers into the struggle with us. Our party must raise the combativity of its organisations to a height that can ensure that they are not taken unawares when civil war breaks out. … The fascists hope to win the civil war by overwhelming brutality and the most resolute violence. Their attack can only be put down by red terror opposed to white terror. If the fascists, armed to the teeth, fire on our proletarian fighters, they will find us ready to wipe them out. If they put one striker in ten up against a wall, the revolutionary workers will shoot one fascist in five! … The Party is ready to fight shoulder to shoulder with anyone who sincerely agrees to fight under the leadership of the proletariat. Forward! Let us close the ranks of the proletarian vanguard! Into battle, in the spirit of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg!14Broué, German Revolution, 736.

When it was announced, this event electrified the masses, who escalated strikes. The SPD and conservatives denounced the event while fascists and the police prepared for a confrontation. When the Anti-fascist Day was banned by the government, the KPD — following the advice of Moscow — backed down.

By the beginning of August, the government was on the brink of collapse. On August 8, Cuno gave a speech in the Reichstag defending his policies and calling for a vote of confidence. As the deputies debated, worker delegations surrounded the Reichstag and demanded Cuno’s resignation. They were ignored. After two days, Cuno got his vote of confidence (the SPD abstained, and the KPD voted against).

In response, anger in the population boiled over into a general strike. Comintern correspondent Victor Serge described the strike and mood as follows:

The big factories in Berlin began passive resistance, systematic go-slow and then more vigorous action. Berlin metalworkers stopped work. Printers too — in particular those working for the Reichsbank; a tube strike had just been ineffectively stifled. In Hamburg, work stopped in the docks. At Lübeck in Saxony, at Emden, at Brandenburg, at Gera, at Lausitz, at Hanover, at Lea, huge mass movements stopped production, brought massive crowds onto the streets, sometimes turned into rioting, and confronted shopkeepers and capitalists with the immediate threat of a revolution.15Victor Serge, Witness to the German Revolution (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2011), 75. Lübeck is not in Saxony.

A mere two days after receiving the support of the Reichstag, Cuno resigned in humiliation. A new government was formed by Gustav Stresemann, who led a grand coalition stretching from the conservatives to the SPD. Stresemann promised to end the Ruhr crisis, reach an agreement with France, and stabilize the mark. Yet Stresemann was not at all confident of success and admitted that he was the final barrier preventing revolution: “We are the last bourgeois parliamentary government,” he said.16International Communist League, “Rearming Bolshevism: A Trotskyist Critique of Germany 1923 and the Comintern,” Spartacist 56 (Spring 2001): 9.

After the Cuno strike, the Communists felt the wind was at their back. Now they began seriously contemplating the possibility of a German Revolution. To that end, a KPD delegation led by Brandler traveled to Moscow in late August to consult the Comintern Executive. The delegation found that the Soviet party was divided on the prospects for a revolution. Zinoviev and Radek did not think the situation was ripe. Joseph Stalin doubted that any revolution was on the horizon in Germany:

Should the [German] Communists strive, at the present stage, to seize power without the Social-Democrats? Are they sufficiently ripe for that? That is the question, in my opinion. When we seized power we had in Russia such resources in reserve as (a) the promise [of] peace; (b) the slogan “land to the peasants”; (c) the support of the great majority of the working class; and (d) the sympathy of the peasantry. At the moment, the German Communists have nothing of the kind. They have, of course, a Soviet country as neighbour, which we did not have; but what can we offer them? If the Government in Germany were to topple over now, in a manner of speaking, and the Communists were to seize hold of it, they will end up in a crash. That is in the “best” case. While, at worst, they will be smashed to smithereens and thrown way back. The whole point is not that Brandler wants to “educate the masses” but that the bourgeoisie plus the rightwing Social-Democrats are bound to turn such lessons — the demonstration — into a general battle (at present all the odds are on their side) and exterminate them [the German Communists]. Of course, the Fascists are not asleep; but it is to our advantage to let them attack first: that will attract the whole working class to the Communists (Germany is not Bulgaria). Besides, all our information indicates that fascism is weak in Germany. In my opinion we should restrain the Germans, not spur them on.17Leon Trotsky, Stalin: An Appraisal of the Man and His Influence, trans. Alan Woods (London: Wellred Books, 2016), 530.

Others in the Soviet party, such as Trotsky, thought the situation in Germany was maturing rapidly and that a decisive battle would take place in the near future. Trotsky argued that preparations for an insurrection needed to begin at once. As he said later,

Precisely for this reason the Communist Party has absolutely no use for the great liberal law according to which revolutions happen but are never made and therefore cannot be fixed for a specific date. From a spectator’s standpoint this law is correct, but from the standpoint of the leader this is a platitude and a vulgarity. … If the country is passing through a profound social crisis, when the contradictions become aggravated in the extreme, when the toiling masses are in constant ferment, when the party is obviously supported by an unquestionable majority of the toilers and, in consequence, by all the most active, class-conscious and self-sacrificing elements of the proletariat, then the task confronting the party — its only possible task under the circumstances — is to fix a definite time in the immediate future, a time in the course of which the favourable revolutionary situation cannot abruptly react against us, and then to concentrate every effort on the preparation of the blow, to subordinate the entire policy and organization to the military object in view, so that this blow is dealt with maximum power.18Leon Trotsky, “Can a Counter-revolution or a Revolution Be Made on Schedule?,” September 23, 1923, in The First Five Years of the Communist International, vol. 2, Marxist Internet Archive.

Eventually, the Soviets decided to give the German Revolution their blessing. Over the objections of Brandler and Radek, Trotsky suggested fixing the date of the uprising as close as possible to the anniversary of the Bolshevik insurrection (November 7) — making the revolution into “the German October.”

Brandler, however, was honest enough to admit that he was not the “German Lenin.” He wanted someone with more experience to lead the forthcoming revolution and asked the Soviets to send Trotsky to Germany. Even though Trotsky was interested, this idea was vetoed by the Politburo. According to Deutscher, Stalin was worried that Trotsky would score another revolutionary victory. Yet as head of the Red Army, Trotsky was involved in preparations for war. If the German insurrection were successful, Britain and France would likely intervene. In response, the Red Army was preparing to send its soldiers through Poland and the Baltic states to aid Germany.19David Stone, “The Prospect of War? Lev Trotskii, the Soviet Army, and the German Revolution in 1923,” International History Review 25, no. 1 (December 2003): 799–817. See also Edward H. Carr, A History of Soviet Russia: The Interregnum 1923–1924 (London: Macmillan, 1954), 215–19. Ultimately, the Red Army never sent its troops, but these mobilizations are a testament that the USSR was willing to risk a general war to support a proletarian revolution in Germany.

Preparations

Despite his doubts, Brandler returned to Germany with plans for an insurrection. The technical preparations for an uprising had already begun. The KPD had an underground apparatus known as the M-Group to handle various aspects of military affairs. The previous year, its organization had been strengthened with help from the Soviet Red Army. As plans for an insurrection gained traction in September, the work of the M-Group picked up speed. It created a general staff known as the Revolutionary Committee (REVKO), headed by August Gulasky (aka Kleine). The REVKO divided Germany into six districts corresponding to the military defense districts of the German army (aka the Reichswehr). These, in turn, were subdivided into districts and subdistricts with a clear chain of command.20Harman, Lost Revolution, 274–75; Angress, Stillborn Revolution, 107, 416–22.

At the subdistrict level, the combat groups were expected to train and drill the Proletarian Hundreds, eventually leading them into battle. The Proletarian Hundreds were originally formed in March by the factory councils as self-defense militias. Now the KPD hoped that they would be the nucleus of a German Red Army. According to the historian Werner Angress, the Proletarian Hundreds had an estimated strength (on paper) of 100,000 fighters by October 1923.21Angress, Stillborn Revolution, 422.

To carry out a revolution, cadre alone — no matter how dedicated — were not enough. The KPD needed arms if it was going to seriously challenge the Reichswehr. Historical sources give wildly different figures, ranging from 600 to 50,000 for the number of rifles at the KPD’s disposal.22Angress, Stillborn Revolution, 422. Even if one accepts the highest estimate for rifles, then the Communists were still seriously outgunned by the Reichswehr. As part of its preparations, the KPD worked to split both the Reichswehr and the police forces. The Reichswehr, however, was an all-volunteer force that carefully screened its recruits to keep Communists, socialists, and Jews out of its ranks. By 1923, much of the Freikorps had been incorporated into the Reichswehr. The police were equally immune from Communist agitation. Yet this does not mean that the Reichswehr and the army would have remained solid in the face of an insurrection. As Arthur Rosenberg argues, “If there had been a really great popular movement against the ruling system, the civil servants — who were after all themselves victims of the inflation — including the police, would hardly have displayed much severity, and whether the Reichswehr soldiers would have fired on their starving fellow-citizens for the sake of exchange profiteers is very doubtful.”23Rosenberg, “Occupation of the Ruhr.”

Trotsky came to an assessment — which he would later revise — that a third of the police would fight the revolutionaries while another third would stay neutral, and the final third would join the KPD. Leon Trotsky, “Revolutionsaussichten in Deutschland,” October 20, 1923, Marxists Internet Archive.

If the KPD launched an insurrection, then it would likely find the full strength of the Reichswehr and the police on the side of the counterrevolution.

To procure arms, Moscow instructed the KPD in October to form workers’ governments. This plan was based on policies developed at the Comintern’s fourth congress in 1922, which focused on the united front. One resolution stated that in certain circumstances a workers’ government supported by the mobilized movement could serve as a transitional step toward the dictatorship of the proletariat. As Trotsky said in December 1922,

If you, our German Communist comrades, are of the opinion that a revolution is possible in the next few months in Germany, then we would advise you to participate in Saxony in a coalition government and to utilize your ministerial posts in Saxony for the furthering of political and organizational tasks and for transforming Saxony in a certain sense into a Communist drillground so as to have a revolutionary stronghold already reinforced in a period of preparation for the approaching outbreak of the revolution. But this would be possible only if the pressure of the revolution were already making itself felt, only if it were already at hand. In that case it would imply only the seizure of a single position in Germany which you are destined to capture as a whole. But at the present time you will of course play in Saxony the role of an appendage, an impotent appendage because the Saxon government itself is impotent before Berlin, and Berlin is — a bourgeois government.24Trotsky, “Report on the Fourth World Congress.”

Trotsky believed that communist participation in a regional government alongside the SPD was a tactic that could only be used in preparation for an insurrection.

Now the Comintern argued that this situation applied in Saxony and Thuringia where the SPD was dependent on the KPD for a legislative majority. As the left wing of the SPD, it was nervous that they would be swept away by the fascists if it didn’t join with the Communists. The KPD was instructed to accept an open SPD invitation to join the government. Afterward, the Communists would use their new positions to prepare popular resistance to an attack from the national government in Berlin. On October 10, the KPD joined the government in both provinces.

Brandler objected to these efforts to accelerate the revolution:

I strongly objected to the attempt to hasten the revolutionary crisis by including communists in the Saxon and Thuringian governments — allegedly in order to procure weapons. I knew, and I said so in Moscow, that the police in Saxony and Thuringia did not have any stores of weapons. Even single submachine guns had to be ordered from the Reichswehr’s arsenal near Berlin. The workers had already seized the local arsenals twice, once during the Kapp putsch, and again in part in 1921. I declared further that the entry of the communists into the government would not breathe new life into the mass actions, but rather weaken them; for now the masses would expect the government to do what they could only do themselves.25Isaac Deutscher, “Dialogue with Heinrich Brandler,” in Fred Halliday, ed., Marxism, Wars, and Revolutions: Essays from Four Decades (New York: Verso, 1984), 162.

As expected, Berlin saw the entry of Communists into provincial governments as a provocation. On October 19, the national government invoked emergency powers and sent the Reichswehr to remove the SPD-KPD governments and disperse the Proletarian Hundreds.

The moment of decision for the KPD was now at hand. On October 21, delegates of factory committees from across the state of Saxony gathered in a hastily convened conference in Chemnitz to decide on their response. Brandler called for a general strike to defend Saxony. He had expected the Social Democrats to agree with the call to arms, instead he was met with icy silence. The conference rejected the call for a general strike and delegated a committee to look into the topic. As August Thalheimer observed: “It was a pauper’s burial of the proposal.”26August Thalheimer, “A Missed Opportunity? The German October Legend and the Real History of 1923,” Marxists Internet Archive; see also Carr, History of Soviet Russia, 221–22.

Bandler believed that Communists could not act alone and after conferring with other KPD leaders, he called off their planned insurrection. As he recalled years later:

After discussions with the other members of the Zentrale, I advised against the proclamation of a general strike, and in this course I received the assent of all the Zentrale members present, including Ruth Fischer… I was of the opinion, and I still am today, that a defensive uprising is condemned to defeat, and should only be risked if there is no other possible way out.27Deutscher, “Dialogue with Heinrich Brandler,” 160.

Even though Radek and other Comintern delegates were not present at Chemnitz, they accepted Brandler’s decision.

What followed was an anticlimax. The army entered Saxony and Thuringia where it ousted the communists without any serious opposition. While the KPD had dispatched couriers across Germany to countermand orders for an uprising, word never reached Hamburg. Two members of the central committee, Hermann Remmele and Ernst Thälmann, left before the end of the Chemnitz Conference. Both were under the impression that the uprising was assured of victory. However, this remains in dispute among historians. Some believe that Thälmann deliberately avoided the message and tried to provoke a national uprising himself. Arriving in Hamburg on October 23, they ordered the Communists to take power. For the next 48 hours, several hundred communist insurgents fought heroically as they occupied several police stations and seized control of portions of the city. Yet they fought alone and defeat was inevitable once the Reichswehr was sent into Hamburg. Aside from the street-fighting at Hamburg, the German October ended before it truly began.28For more on the Hamburg uprising, see Larissa Reissner, Hamburg at the Barricades: And Other Writings on Weimar Germany (London: Pluto Press, 1977); A. Neuberg, Armed Insurrection (London: New Left Books, 1970), 81–104. As Angress observed, the Hamburg uprising gained unearned mythical status in the party due to the participation of future KPD leader Ernst Thälmann: “The Hamburg barricades became the party’s Thermopylae, and Thälmann its Leonidas.” Angress, Stillborn Revolution, 451.

The Aftermath

In the following days, the German government seized the initiative. On November 3, the KPD was declared illegal, its press was suspended, and its activists were arrested. A few days later, on November 8–9, Adolf Hitler staged his famous beer hall putsch in Munich, which was quickly put down. By the middle of November, order had been restored throughout Germany.

The debacle in Germany immediately led to a huge debate in the USSR and the Comintern over what had gone wrong. While this was a necessary discussion, it occurred just as bureaucratization was accelerating in Russia. This meant that any discussion immediately became embroiled in the inner-party struggle between Trotsky and the troika of Stalin, Zinoviev, and Kamenev. At first, Zinoviev accepted that the retreat was necessary, and he minimized the defeat.

The ultraleftist Ruth Fischer said that the KPD should have given battle even at the risk of defeat. Fischer, now backed by Zinoviev, blamed Brandler for the defeat. New research by Ralf Hoffrogge confirms that Fischer was completely passive in October, making her an armchair insurrectionist. 29See Ralf Hoffrogge, A Jewish Communist in Weimar Germany The Life of Werner Scholem (1895–1940) (Boston: Brill, 2017), 322-26. In January 1924, both Brandler and Thalheimer were removed from the KPD’s leadership in disgrace. As Victor Serge recalled, this was a sign of the Comintern’s growing bureaucratization: “But now the ECCI [Executive Committee of the Communist International], solicitous above all for its own prestige, condemns the ‘opportunism’ and inefficiency of the two leaders of the KPD, Brandler and Thalheimer, who have been so incompetent in managing the German Revolution. But they did not dare move a finger without referring the matter to the Executive!”30Victor Serge, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (New York: New York Review of Books, 2012), 204.

Even though Trotsky had criticized Brandler’s leadership, he objected to the Comintern’s summarily removing a foreign party leader. As he said sometime later, “In [Brandler’s] case as in others, I fought against the inadmissible system which only seeks to maintain the infallibility of the central leadership by periodic removals of national leaderships, subjecting the latter to savage persecutions and even expulsions from the party.”31Leon Trotsky, The Third International after Lenin (New York: Pathfinder Books, 1996), 119–20. Trotsky believed that the responsibility for the German defeat lay with the Comintern, which had failed to act until many crucial months had already passed. The Comintern, however, shrank from assessing its role in the defeat. As a result, no sober balance sheet was drawn on the German October.

Assessment

We are left with the question of why the German Revolution was defeated. Even though Brandler was no Lenin, he was not solely to blame. The KPD itself possessed several major weaknesses that prevented it from taking advantage of the revolutionary situation in 1923. First: the KPD had experienced organizers and fighters but no leaders who could take the place of either Luxemburg or Liebknecht. To compensate for their lack of experience, Brandler and Thalheimer looked to Moscow for guidance. Second: the KPD leaders made crucial errors on the road to power. For example, at Chemnitz, they gave the Social Democrats veto power over the revolution. As the historian Evelyn Anderson pointedly noted, “The Communist position was manifestly absurd. The two policies of accepting responsibility of government, on the one hand, and of preparing for a revolution, on the other, obviously excluded each other. Yet the Communists pursued both at the same time, with the inevitable result of complete failure.”32Evelyn Anderson, Hammer or Anvil: The Story of the German Working-Class Movement (London: Victor Gollancz, 1945), 95.

Contrary to the claims of Anderson, the workers’ government tactic was not an impossible contradiction. As Trotsky argued, the purpose of the workers’ government was to establish “fortresses” that could strengthen the factory councils, Proletarian Hundreds, etc., into a network of self-organization and self-defense bodies. This would enable the Communists to organize a national insurrection under the banner of defending the workers’ governments against the Reichswehr. The problem was that, once the SPD opposed a general strike, the KPD leadership transformed the workers’ governments into ends in themselves after they backed down from revolution. Instead of acting as a launching pad for revolution, the workers’ governments ended up as dead weights.

This analysis of the German October’s defeat assumes that the situation was objectively revolutionary. But according to others, such as Brandler and Thalheimer, the balance of forces in Germany did not favor a revolution in 1923. Thalheimer, for example, argued that after the August strikes, the Stresemann government could have stabilized Germany. In addition, the entrance of the Social Democrats into the grand coalition fostered reformist illusions in the working class. As Thalheimer said, “When we had discussions with the Social Democrats we found that they placed high hopes on the entry to the government of Hilferding. Social Democrats who, quite spontaneously, had stood shoulder to shoulder with us in every struggle, who had joined in the strike against Cuno, the whole mass of them were filled with new illusions.”33Thalheimer, “A Missed Opportunity?” By September, Stresemann managed to stabilize the mark and ended passive resistance in the Ruhr. Given the unfavorable objective circumstances, the masses were unwilling to fight for power.

Thalheimer’s position, however, assumes that the mass of the workers accepted in advance that Stresemann’s plans would prevail. This was far from the case. The end of passive resistance was not immediately followed by an agreement with the French. Inflation was still rampaging Germany in the autumn of 1923. Contrary to Thalheimer’s claims, the workers had little reason to believe that Stresemann would succeed where other governments had failed.

Trotsky offered an alternative rationale for the failure of the German October. He concurred with Thalheimer that the Cuno strike was the crest of the revolutionary wave:

True, in the month of October a sharp break occurred in the party’s policy. But it was already too late. In the course of 1923 the working masses realized or sensed that the moment of decisive struggle was approaching. However, they did not see the necessary resolution and self-confidence on the side of the Communist Party. And when the latter began its feverish preparations for an uprising, it immediately lost its balance and also its ties with the masses.34Leon Trotsky, “Author’s 1924 Introduction,” in The First Five Years of the Communist International, vol. 1, Marxists Internet Archive.

Yet the KPD should not have stood down. Into the autumn, the political situation in Germany remained fluid, and an offensive by the Communist Party could still unveil the true balance of forces, as Trotsky noted: “Only a pedant and not a revolutionist would investigate now, after the event, how far the conquest of power would have been ‘assured’ had there been a correct policy.”35Trotsky, Third International after Lenin, 117. Success may not have been certain in October, but the KPD still had an opening that it failed to exploit. Its mistake in October only culminated its failure to keep up with events throughout the summer.

Because the KPD failed to provide leadership at the decisive moment, the bourgeoisie was able to seize the initiative and defeat it. As he wrote in The Third International after Lenin, Trotsky did not believe this outcome was inevitable:

In the summer of 1923, the internal situation in Germany, especially in connection with the collapse of the tactic of passive resistance, assumed a catastrophic character. It became quite clear that the German bourgeoisie could extricate itself from this “hopeless” situation only if the Communist Party failed to understand in due time that the position of the bourgeoisie was “hopeless” and if the party failed to draw all the necessary revolutionary conclusions. Yet it was precisely the Communist Party, holding the key in its hands, that opened the door for the bourgeoisie with this key.

Why didn’t the German revolution lead to a victory? The reasons for it are all to be sought in the tactics, not in the existing conditions. Here we had a classic example of a missed revolutionary situation. After all the German proletariat had gone through in recent years, it could be led to a decisive struggle only if it were convinced that this time the question would be decisively resolved and that the Communist Party was ready for the struggle and capable of achieving the victory. But the Communist Party executed the turn very irresolutely and after a very long delay. Not only the Rights but also the Lefts, despite the fact that they had fought each other very bitterly, viewed rather fatalistically the process of revolutionary development up to September-October 1923.36Trotsky, Third International after Lenin, 116–17.

Trotsky argued that the KPD needed to act in October. Even if the moment to act had passed by then, the KPD still let many opportunities pass by. These possibilities went untested since the party had a certain level of conservatism that prevented it from taking the offensive. As Trotsky said in The Lessons of October, this conservatism was only natural, since most of the time the opportunity to take power does not exist:

This preponderance manifests itself in daily life, at every step. The enemy possesses wealth and state power, all the means of exerting ideological pressure and all the instruments of repression. We become habituated to the idea that the preponderance of forces is on the enemy’s side; and this habitual thought enters as an integral part into the entire life and activity of the revolutionary party during the preparatory epoch. The consequences entailed by this or that careless or premature act serve each time as most cruel reminders of the enemy’s strength.37Leon Trotsky, “On the Eve of the October Revolution — the Aftermath,” chap. 6 in The Lessons of October, Marxists Internet Archive.

The decision to struggle for power was not just a matter of this or that decision by a particular leader but required a complete transformation in the party’s outlook. Thus, it is unsurprising that sections of the party dragged their feet and refused to make the needed changes. The confusion inside the party affected the class as well:

On one and the same economic foundation, with one and the same class division of society, the relationship of forces changes depending upon the mood of the proletarian masses, the extent to which their illusions are shattered and their political experience has grown, the extent to which the confidence of intermediate classes and groups in the state power is shattered, and finally the extent to which the latter loses confidence in itself.38Trotsky, “On the Eve of the October Revolution.”

Throughout a good portion of 1923, the KPD showed more confidence in the stability of German capitalism than the bourgeoisie itself. Rather than taking advantage of fault lines in the enemy camp, the KPD ended up inadvertently giving the bourgeoisie an opportunity to regroup. While the Communists had a base of millions on their side, they failed to show them a way out. As a result, the workers lost confidence in the KPD, shifting to the SPD and the right-wing parties.

It is not voluntarist to claim that the German October was a missed opportunity. Based on Lenin’s three criteria outlined above, Germany was in a revolutionary situation in 1923: (1) the German ruling class proved unable to handle the crisis throughout the year, resulting in governmental paralysis; (2) hyperinflation and economic collapse had exponentially increased the suffering of the dominated classes; and (3) the strikes, mass actions, and growth of the factory councils and Proletarian Hundreds signaled an increase in working-class self-activity.

The failure in 1923 was due to vacillating leadership. During the first half of 1923, the KPD had not grasped the possibility of revolution, and then, after the Cuno strikes, it rushed almost haphazardly toward an insurrection. Yet the KPD could have made different decisions. It could have coordinated and led the nationwide strike movement in the summer rather than let this scattered resistance sputter out. This would have placed the KPD in a better position to lead the masses in a civil war.

Appealing to the nationalist Right was both a violation of principle and a waste of effort for no gain. Instead, the KPD could have focused on mobilizing a united front against the Right on Anti-fascist Day. This event could have galvanized the workers and positioned the Communists for leadership over a mass movement. Anti-fascist Day could even have started the KPD’s fight for power. Yet after the Anti-fascist Day was banned, the KPD leadership feared any premature action and refused a contest.

This vacillation in the party’s upper echelons prevented them from taking the initiative at favorable moments in 1923. As Trotsky observed, a revolutionary party — no matter its size or the depth of the capitalist crisis — can hope to lead the working class only by mastering the whole arsenal of strategy and tactics, along with developing a tested core of leaders who can put them into practice. Ultimately, the KPD failed to overcome its internal weaknesses to rise to the challenge in 1923.

Even if the KPD had made its bid in October and failed, it would have been better to go down fighting than surrender without a battle. As the Communist Rosa Leviné-Meyer said after the insurrection was called off,

A retreat may have been inevitable. But not such a catastrophic and defenseless retreat. The workers were never able to find out by their own experience whether the revolution was “betrayed” or whether they lost the battle in a square fight, not yet being strong enough to achieve their goal. They felt humiliated and cheated.39Rosa Leviné-Meyer, Inside German Communism: Memoirs of Party Life in the Weimar Republic (London: Pluto Press, 1977), 56.

This is not a call for needless bloodshed. If every avenue is cut off and there is no other option, then it is better to go down fighting than to wave a white flag without a struggle. The latter will do far more to demoralize the working class than the former. While communists may not be able to avert defeat, they are responsible for the state in which workers emerge from it: either dispirited and apathetic or energized and ready to resume the struggle. A heroic defeat in October 1923 could have inspired the workers in future battles. That was a valuable contribution that the KPD could have made instead of retreating. The Stalinists did this after the fact by idealizing the Hamburg Uprising and Thälmann’s role in it, while masking the Comintern leadership’s failure as a whole.

Not only was the defeat without a struggle demoralizing for the working class and the party, but it was also felt materially in working and living conditions. Just as the workers paid for the passive resistance in the Ruhr with soaring prices while capitalists kept the mines open, now they were made to pay by the bourgeoisie again: the eight-hour day was abolished, and once the Rentenmark was stabilized in November, unemployment shot up dramatically.

The Failure to Turn

Looking back a hundred years later, we can conclude that the German October was a moment when history failed to turn. The stormy year of 1923 showed that workers in advanced capitalist countries were not immune to communist politics. After the Russian Revolution, the German October was one of the best opportunities for the workers to seize power in the world. Unfortunately, this opportunity was lost, and the German October marked an end to the revolutionary wave that had begun in 1917. After 1923 came the isolation of Soviet Russia and, 10 years later, the rise of Hitler’s counterrevolution. If we want to ensure that history turns to socialism at the next opening, then it is crucial to develop a party and leaders who can take advantage of a revolutionary situation. The German October failed to turn because the KPD lacked this type of tested leadership.

Notes

| ↑1 | Ruth Fischer, Stalin and German Communism: A Study in the Origins of the State Party (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1948), 312. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Werner T. Angress, Stillborn Revolution: The Communist Bid for Power in Germany, 1921–1923 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1963), 285, 350. |

| ↑3 | Pierre Broué, The German Revolution 1917–1923 (Boston: Brill, 2005), 712. |

| ↑4 | Broué, German Revolution, 714. |

| ↑5 | V. I. Lenin, “Collapse of the Second International” (1915), Marxists Internet Archive. |

| ↑6 | Broué, German Revolution, 577. |

| ↑7 | Chris Harman, The Lost Revolution: Germany 1918 to 1923 (London: Bookmarks, 1982), 246. |

| ↑8 | Arthur Rosenberg, “The Occupation of the Ruhr and the Inflation, 1923,” chap. 7 in A History of the German Republic (1936), Marxists Internet Archive. |

| ↑9 | Harman, Lost Revolution, 251. |

| ↑10 | Angress, Stillborn Revolution, 318–19. |

| ↑11 | Karl Radek, “Leo Schlageter: The Wanderer into the Void” (June 1923), Marxists Internet Archive. In 1933, the philosopher and Nazi Party member Martin Heidegger also praised Schlageter as an authentic hero for Germany: “Schlageter died the most difficult of all deaths. Not in the front line as the leader of his field artillery battery, not in the tumult of an attack, and not in a grim defensive action—no, he stood defenseless before the French rifles. But he stood and bore the most difficult thing a man can bear. Yet even this could have been borne with a final rush of jubilation, had a victory been won and the greatest of the awakening nation shone forth.” Martin Heidegger, “Schlageter (May 26, 1933),” in Richard Wolin, ed., The Heidegger Controversy: A Critical Reader (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993), 42. |

| ↑12 | Angress, Stillborn Revolution, 339–40. Years later, Fischer defended her remarks as follows: “At a meeting of Berlin University students organized by the Berlin party branch, I was the speaker. The attitude of the nationalists against capitalism was discussed, and I was obliged to answer some anti-Semitic remarks. I said that Communism was for fighting Jewish capitalists only if all capitalists, Jewish and Gentile, were the object of the same attack. This episode has been cited and distorted over and over again in publications on German Communism”; Fischer, Stalin and German Communism, 283. |

| ↑13 | Fischer, Stalin and German Communism, 291–92. |

| ↑14 | Broué, German Revolution, 736. |

| ↑15 | Victor Serge, Witness to the German Revolution (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2011), 75. Lübeck is not in Saxony. |

| ↑16 | International Communist League, “Rearming Bolshevism: A Trotskyist Critique of Germany 1923 and the Comintern,” Spartacist 56 (Spring 2001): 9. |

| ↑17 | Leon Trotsky, Stalin: An Appraisal of the Man and His Influence, trans. Alan Woods (London: Wellred Books, 2016), 530. |

| ↑18 | Leon Trotsky, “Can a Counter-revolution or a Revolution Be Made on Schedule?,” September 23, 1923, in The First Five Years of the Communist International, vol. 2, Marxist Internet Archive. |

| ↑19 | David Stone, “The Prospect of War? Lev Trotskii, the Soviet Army, and the German Revolution in 1923,” International History Review 25, no. 1 (December 2003): 799–817. See also Edward H. Carr, A History of Soviet Russia: The Interregnum 1923–1924 (London: Macmillan, 1954), 215–19. |

| ↑20 | Harman, Lost Revolution, 274–75; Angress, Stillborn Revolution, 107, 416–22. |

| ↑21 | Angress, Stillborn Revolution, 422. |

| ↑22 | Angress, Stillborn Revolution, 422. |

| ↑23 | Rosenberg, “Occupation of the Ruhr.”

Trotsky came to an assessment — which he would later revise — that a third of the police would fight the revolutionaries while another third would stay neutral, and the final third would join the KPD. Leon Trotsky, “Revolutionsaussichten in Deutschland,” October 20, 1923, Marxists Internet Archive. |

| ↑24 | Trotsky, “Report on the Fourth World Congress.” |

| ↑25 | Isaac Deutscher, “Dialogue with Heinrich Brandler,” in Fred Halliday, ed., Marxism, Wars, and Revolutions: Essays from Four Decades (New York: Verso, 1984), 162. |

| ↑26 | August Thalheimer, “A Missed Opportunity? The German October Legend and the Real History of 1923,” Marxists Internet Archive; see also Carr, History of Soviet Russia, 221–22. |

| ↑27 | Deutscher, “Dialogue with Heinrich Brandler,” 160. |

| ↑28 | For more on the Hamburg uprising, see Larissa Reissner, Hamburg at the Barricades: And Other Writings on Weimar Germany (London: Pluto Press, 1977); A. Neuberg, Armed Insurrection (London: New Left Books, 1970), 81–104. As Angress observed, the Hamburg uprising gained unearned mythical status in the party due to the participation of future KPD leader Ernst Thälmann: “The Hamburg barricades became the party’s Thermopylae, and Thälmann its Leonidas.” Angress, Stillborn Revolution, 451. |

| ↑29 | See Ralf Hoffrogge, A Jewish Communist in Weimar Germany The Life of Werner Scholem (1895–1940) (Boston: Brill, 2017), 322-26. |

| ↑30 | Victor Serge, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (New York: New York Review of Books, 2012), 204. |

| ↑31 | Leon Trotsky, The Third International after Lenin (New York: Pathfinder Books, 1996), 119–20. |

| ↑32 | Evelyn Anderson, Hammer or Anvil: The Story of the German Working-Class Movement (London: Victor Gollancz, 1945), 95. |

| ↑33 | Thalheimer, “A Missed Opportunity?” |

| ↑34 | Leon Trotsky, “Author’s 1924 Introduction,” in The First Five Years of the Communist International, vol. 1, Marxists Internet Archive. |

| ↑35 | Trotsky, Third International after Lenin, 117. |

| ↑36 | Trotsky, Third International after Lenin, 116–17. |

| ↑37 | Leon Trotsky, “On the Eve of the October Revolution — the Aftermath,” chap. 6 in The Lessons of October, Marxists Internet Archive. |

| ↑38 | Trotsky, “On the Eve of the October Revolution.” |

| ↑39 | Rosa Leviné-Meyer, Inside German Communism: Memoirs of Party Life in the Weimar Republic (London: Pluto Press, 1977), 56. |