Wendy Z. Goldman is a history professor specializing in Russian history. Her study of women’s liberation in revolutionary Russia — Women, the State, and Revolution — was published back in 1993. It has since been published in Spanish by Ediciones IPS and in Portuguese by Edições Iskra, two publishes connected to Left Voice’s sister publications. She gave the following talk in Madrid and Barcelona on September 12 and 15 to present this book.

Today, women are demanding changes that women 100 years ago could not have imagined, and this is because so many struggles have been won. The conditions that women face today, their problems, and their issues are different that those confronting women in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, when socialist feminists like Clara Zetkin, Aleksandra Kollontai, Inessa Armand, Aleksandra Artyukhina, and others first developed a program for emancipation. In most of the developed world, women have entered the waged labor force, won the right to vote and to participate in the public sphere, gained access to higher education, to the professions, and to competitive sports. We won the right to contraception and to control our own sexuality. We fought and passed laws against sexual harassment and disrespect. We challenged oppressive gender roles and stereotypes, and achieved greater equality with men at home and at work. In many countries, LGBTQ people have won new freedoms, social recognition, and legal rights. The changes in my own lifetime have been enormous.

At the same time, throughout many parts the world, there is a fierce patriarchal reaction, often driven by organized religion, male backlash, and authoritarian states. This reaction seeks to rob women of the advances we have made and the freedoms that we have won. Today, in the United States, for example, American women in many states recently lost the right to abortion, and we are now fighting battles that we thought were long over. Mothers and daughters demonstrate together for reproductive freedom as mothers remember the horror and fear of illegal abortion and daughters face new and intrusive controls on their bodies and their rights.

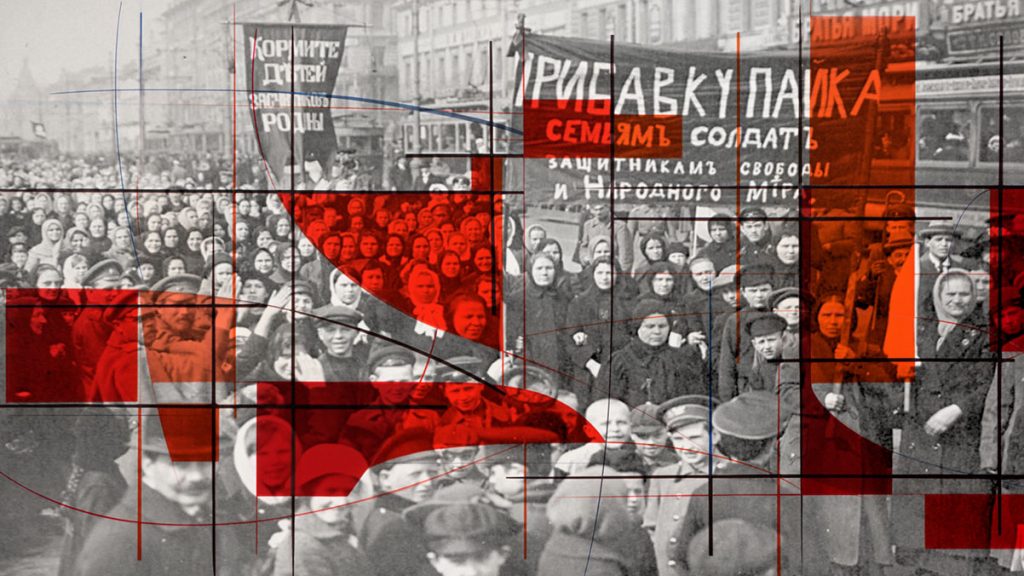

Today, I want to share with you a forgotten chapter from Soviet history, a chapter that belongs to us and is an important part of the long struggle of feminists and socialists. I want to take us back in time to a great moment in history when workers, peasants, women, and revolutionaries seized power and it seemed possible to remake every aspect of society. This moment was the Russian revolution in October 1917.

When the soviets came to power in October 1917, revolutionaries had a vision of women’s liberation that was very radical. It aimed to completely transform the family and to create genuine conditions for women’s equality in the larger society. This vision was only partially implemented for many political, social, and economic reasons. But it still holds many lessons for us today.

The Russian revolutionaries had a vision of women’s liberation that rested on four principles. First, “free love” or “free union.” Second, women’s emancipation through economic independence. Third, the socialization of household labor. And fourth, gradual and inevitable disappearance of the family as a unit regulated by Church and state.

“Free union” or “free love” was a term that was widely popular in the nineteenth century. It meant that relationships and marriage should be based on mutual attraction and respect. Relationships should be free of economic constraint, parental control, and dependence. They should be free of the interference by either religious authorities or the state. People should make their own choices about who to love. No person should have to remain in a relationship where love no longer existed or where they were abused. No external power should force anyone to contract or remain within a marriage if they wanted to be free.

At the time of the revolution, people in the new Soviet society debated: What would love look like in a socialist society? How long were such “free unions” likely to last? Would they last lifetime, several years, a few days, or perhaps only a few hours? Many at the time believed that no shame or value should be attached to length of a union. It would be only as long as both people agreed. One Soviet sociologist wrote at the time, “The duration of marriage will be defined solely by the mutual inclination of the spouses.”

For unions to be truly “free,” people needed the legal right to divorce (which did not exist before the revolution), and also, they required the ability to support themselves, to be economically independent. Women, in particular, needed to have access to a fair and independent wage, which would allow them to support themselves and their families, and to escape dependency on men. The Bolsheviks believed that women’s participation in the labor force had another benefit as well. It would not only give women economic independence from men, but it would also introduce them to a wider world beyond the kitchen and the home. They would become full and equal participants in the new society, no longer confined to the narrow world of the home, housework, and the family.

Yet once women entered the waged labor force on an equal basis with men, who would perform the household labor previously done by women in the home for free? Household labor (or in Marxist terms, reproductive labor), namely the care of children, washing, cleaning, cooking, care of elderly and the sick, was essential to society. Once women entered the public sphere to work for wages and participate in the wider society, the new Soviet state planned to socialize most reproductive labor. These tasks would be transferred to the larger economy, transformed into respected work, performed by men and women, for good wages. People would be able to eat in neighborhood dining halls, and have access to laundries and daycare centers for their children. In addition, the Soviet state passed strong maternity legislation to protect women, provided paid time off before and after birth, guaranteed that a woman’s job be held for her after the birth of a child, and offered protections for nursing mothers. At the time, this package of legislation was the strongest in the world.

This vision, stressing the socialization of reproductive labor, differed from the contemporary feminist demand that men and women share household labor equally. The revolutionary idea was to socialize household labor, not fight over it. It also differed from the more contemporary demand launched by women in the 1970s under the slogan, “Wages for Housework,” which demanded that the state pay women a wage for the work that they performed in the home, or the current idea that everyone should work shorter hours in order to have more time to spend with children or on household labor. The new Soviet government sought dissolve traditional gender roles entirely by creating communal institutions to perform household labor. It did not plan to leave household labor (either paid or unpaid) centered within the traditional family in the hands of women.

The fourth element of the revolutionary Soviet vision, perhaps the most radical of all, was “the withering away” (in Russian, otmiranie) of the family. As Marxists, many Soviet revolutionaries believed that the family was a mutable or changeable institution that assumed a different form in various epochs. Its form was tied to the mode of production. The peasant family under feudalism, for example, took a different form than the nuclear family of workers under capitalism. Every family form had its own social relations between men and women, ways of rearing children, customs, traditions, and habits. The form was not fixed and eternal but subject to change. And just as the family form under capitalism differed from that of feudal or tribal society, the family form under socialism would differ from its previous incarnations.

Under socialism, the family would cease to have an economic function, it would no longer be an organization to pass down property, women would no longer be controlled by men, and children would no longer be separated into “legitimate” and “illegitimate” categories in terms of their rights. There would be no need to regulate the family by law. People would come together or separate as they wished. They would have no need to get married. Children would be supported and cared for regardless of whether their parents were married or not. Once economic dependency was eliminated, the family as an economic unit would eventually “wither away.” Loving relations between parents and children and between partners would continue to exist, but not in any form mandated by the state or religion.

These ideas about the family were also closely related to revolutionary ideas about law. The Bolsheviks and many revolutionaries at the time believed that within a short period, the state and law would also eventually wither away. Jurists had exciting debates over the nature of law. Did it represent the written power of one class over another? Or was it the result of classes in conflict? How soon would law under socialism take a new form? They all believed that in a society without poverty and class exploitation, crime would largely disappear. Eventually, criminal law and coercive state power would become superfluous. Likewise, in the absence of capitalist corporations and private enterprise, civil law regulating corporate rights would also become unnecessary. Socialist jurists differed over how quickly criminal, family, and civil law would become outmoded, but they agreed that under socialism, an entirely new relationship to law itself would develop.

Alexander Goikhbarg, the young revolutionary who helped draft the 1918 Family Code, said at the time, “Of course in publishing these law codes, proletarian power does not want to rely on them for very long. Proletarian power constructs its laws dialectically, so that every day of their existence undermines the need for their existence.” In short, the aim of law was to make law superfluous.

The group most committed to this vision of a new life, or in Russian, novyi byt, for women, was the Zhenotdel or Women’s Department within the Communist Party. It was created in response to strong pressure from women party members, and its purpose was to remake daily life for women. The creation of a separate organization devoted to organizing women around their own interests was not easy. Many party members, male and female, disagreed with the idea of female “separatism,” an idea they associated with bourgeois feminism. They believed that women should join organizations such as trade unions or the Party, and not segregate themselves in special groups. The establishment of the Zhenotdel was the result of a sharp struggle between male and female communists within the Party.

The organization was composed of delegate assemblies and local commissions. The delegate assemblies elected working-class and peasant women, called delegatki, and placed them in various branches of government for short periods of time so they could learn how to govern. Many delegatki went on to take leading posts in the government and the Party. The women’s commissions worked on the local level to establish child care centers, laundries, and dining halls.

The Zhenotdel organized hundreds of thousands of women throughout the Soviet Union. It fought against female unemployment, combated prostitution, and provided education for working women and housewives. In the 1920s, its activists, known in Russian as bytoviki, faced great obstacles: a lack of state funds for social services and high female unemployment. Millions of children had been orphaned by World War I, the Civil War, and a terrible famine in 1921. Moreover, at the lower levels of the Party and in the unions, many men remained hostile to women’s issues and to women organizing among women.

On the legal front, the new soviet state also took radical action. Within less than a year, the new socialist government introduced a Family Code that put the revolutionary vision into law. The 1918 Family Code swept away centuries of patriarchal and Church power. It was the most progressive family legislation the world had ever seen. The Code was the first in the world to create full equality for women under the law. It established civil marriage (which did not exist in tsarist Russia) in place of religious marriage. Although people could still get married in church if they wished, religious ceremonies were no longer recognized by the state. The Code allowed divorce at request of either spouse, and no grounds were needed. It provided equal right to alimony for men and women who were disabled and poor. It abolished the concept of illegitimacy and entitled all children to parental support regardless of whether they were born within or outside marriage. In 1920, SU became the first country in the world to legalize abortion, and to make abortion available in hospitals, to make it safe, free, and legal.

In 1927, after intense nationwide debate, Code became even more radical. In an effort to encourage new forms of partnerships and to provide legal protection for people who were not married, it recognized de facto marriage or cohabitation as the legal equal of civil marriage. Cohabitation received the same legal rights as marriage, thus undercutting the need for people to marry at all. The Code also further simplified the divorce procedure, moving it out of the courts to the registry offices. Either spouse could go to registry office to fill out a short form for divorce. If their spouse was not present, they would be notified of the divorce by postcard! This provision became known as the famous Soviet “postcard divorce.”

The radical legislation coupled with rapid changes in personal attitudes and morality, however, began to produce some serious social problems that had a negative rather than an emancipatory influence on women. Divorce was so simple that many men married and divorced multiple women, often leaving each one with a child. High unemployment for women in the 1920s made divorce especially painful. Many women were dependent on their husbands for support. Women who did divorce could not support themselves and had trouble collecting alimony and child support. The courts overwhelmed by desperate women petitioning for alimony and child support. Studies of prostitutes showed that most were former workers who had lost their jobs to returning veterans and could not find employment. Many had children or elderly parents to support, and were forced to sell themselves on the streets for money. Moreover, even if a woman did have a job, there were few public dining halls, laundries, or childcare centers. In 1920s, the government was trying to rebuild the economy after years of ruin during World War I and the Civil War. In this reconstruction period, the country had few resources available for social services.

Peasants, who constituted the majority of the country, also had trouble with the new law. The peasant household was multigenerational, patrilocal, and patriarchal. Its property – land, animals, tools – was held in common by the extended family and could not be divided. The cow, for example, could not be cut in half. A peasant woman could not live independently in the village, making divorce very difficult.

Finally, in 1920, when abortion was legalized, most male jurists and medical experts believed that once material conditions improved, women would not want to have abortions. This idea turned out the be false. Women turned to abortion in high numbers, not only because they were unable to support a child, but also because they did not want to have children at a particular time. Students who wanted to study, women who wanted to work, mothers with many children, and others all turned to abortion for personal reasons that were not necessarily based in poverty or material difficulty. Contraception barely existed and women wanted to be able to control their fertility. As abortion rate increased, the state became increasingly concerned about the decrease in birthrate.

In 1930, after fierce struggles against the Left and Right oppositions, Stalin assumed unchallenged leadership within the Party, and moved forward with a program of rapid industrialization and collectivization of the peasantry. Women entered the industrial labor force in record numbers, and cities and industrial towns grew rapidly. Millions of peasants left the countryside. Between 1928 and 1937, 6.6 million women entered the workforce. In no country of the world did women constitute such a significant part of the working class in so short a time. The Party launched a new slogan: “Face to Production,” which affected every area of life. All organizing, goals, and ideals were subordinated to meeting the first five-year plan, an approach known as “productionism.”

That same year, the Central Committee abolished the Zhenotdel claiming that it replicated the work of other organizations. Despite strong protests from women activists, Party leaders instructed them to stop organizing around issues of byt or daily life and concern themselves with raising production in the factories and on the new collective farms. It was a great irony that women lost the one organization capable of articulating their needs and remaking daily life just at the point they gained access to an independent wage.

Under Stalin, there was a strong ideological shift in the state’s attitude toward the family. Industrialization and collectivization created massive upheaval and social disorder throughout the country. Judges, educators, social workers, and the militia became increasingly concerned by the large numbers of orphaned and neglected children on the streets. The state began searching for new solutions to social problems, and it turned away from the early progressive vision in favor of more repressive alternatives. Jurists, who once approached juvenile crime as a product of social and material conditions, now argued that it was the result of parental irresponsibility. Women pressured the courts to find and to prosecute men who failed to support their children. One writer urged that men who abandoned women or treated them solely as “bed partners” should be charged with the crime of “sexual hooliganism.” The state launched a great propaganda campaign in favor of the stable family and against male irresponsibility. It passed a new law that increased punishment for nonpayment of alimony, and made divorce became more difficult to get. The practice of “postcard divorce” ended and the law established increasing fees for each subsequent divorce. In 1936, the state passed a law prohibiting abortion and criminalizing abortion providers. It included strong material incentives to encourage women to have more children.

Official state ideology now rejected idea that the family would “wither away“ under socialism. Propaganda now emphasized the “strong socialist family.” During the Terror, many of the early revolutionary jurists were arrested and executed for “legal nihilism,” or idea that the state, law and family would eventually wither away under socialism. By the end of the 1930s, Stalin and the Party’s leaders rejected and reversed many of the earlier social and political ideas of the revolution. The great reversal was in part a result of social pressure from below to stabilize society by resurrecting traditional family bonds and responsibilities. Yet party leaders also made an ideological choice to promote the family and stable unions, and the reject the early revolutionary vision. The overwhelming majority of women did not support the criminalization of abortion. Women continued to try to control their fertility, and they were forced underground. After a brief increase in the birthrate, it soon began to fall again as women resorted to the dangerous practice of illegal abortion.

At the same time, the state did not reject all the elements of the early emancipatory vision. Women moved into the work force in record numbers. They took skilled jobs in industry and the professions that were previously reserved for men. The state created daycare centers, dining halls, and laundries. These services became a fixed feature of Soviet life, and were widely used by people. People often ate their main hot meal at work or at school in expensive, subsidized dining halls, lifting some of the burden for cooking from women. Yet women still remained responsible for most household tasks. Cultural attitudes toward gender roles were slow to change. Women assumed what we call today “the double burden”: working for wages and doing most of the household labor.

What relevance does the revolutionary vision have for us today, more than a century after the soviets first took power? The problem of the double burden has still not been solved. Women with families who work for wages are stressed out, exhausted, and resentful. Under capitalism, neither state nor private institutions have kept pace with the need for high quality, inexpensive childcare. Household labor has not been socialized, and it is still mainly performed by women. Capitalism offers two solutions, but neither is adequate to the problem, and both work most effectively for the wealthy. The first solution is that wealthier families hire poor women, immigrants, or low-paid workers, to do the family’s household work. The second solution is that household work is transformed into a for-profit business, through restaurants, daycare centers, laundries, maid services, and elder care homes. These services, which all families depend on to some degree, provide better quality at a higher cost. Small children with working mothers receive a level of care commensurate with their family’s resources.

The problem of household labor has now taken a global form. Millions of men and women are forced by economic necessity to leave their own countries and their own families to seek work in other places. Maids, babysitters, and eldercare workers now cross borders to work in the service sector of countries thousands of miles from their homes. The servants in Qatar and Saudi Arabia come from Pakistan and India; in the United States, women from the Philippines, Latin America, and the Caribbean do service and household labor. Many people live illegally without papers and without protection. They are forced to leave their own children behind. This is hardly a solution to the problem. The Bolsheviks had a vision one hundred years ago of what emancipation for women might look like. The question before us now is: what kind of system can emancipate ALL women, not just a small elite? In the words of the old American labor song, “Pass it On”:

Freedom doesn’t come like a bird on the wing

Doesn’t come down like the summer rain

Freedom, freedom is a hard-won thing

You’ve got to work for it,

fight for it, day and night for it

And every generation has to win it again

First published in Contrapunto on September 16, 2023.