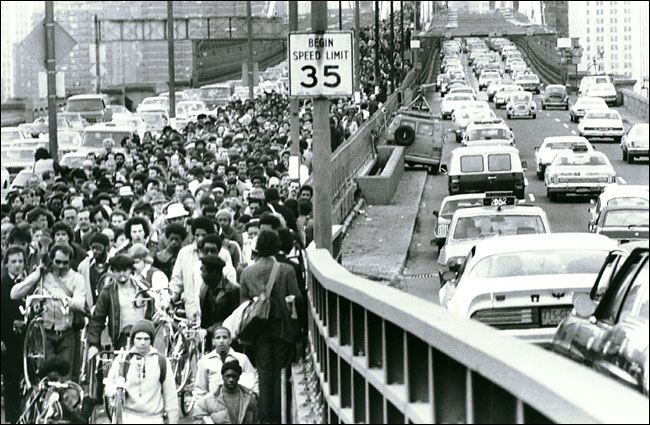

Image of the 1966 New York City subway workers strike from Transport Politic.

In the U.S., the huge defeat of the air traffic controllers’ strike in 1981 ushered in an era of attacks on the working class and on labor unions. Reagan´s presidency marked the beginning of the neo-liberal era , and with it, the loss of labor rights and the hard-fought gains of the past. At the same time, capitalism expanded to former workers’ states, bringing about unprecedented profit for the international bourgeoisie. It was the “end of history” and thanks to the propaganda of American academia and to the offshoring of jobs, many argued that the working class no longer existed.

Because of this state-supported amnesia, some make the ahistorical claim that strikes are foreign to U.S. culture. They argue that we don’t see strikes in the U.S. the way we do in Latin America or Europe because American workers simply don’t want to strike.

This is markedly untrue. In 1886 alone, workers led over 1,400 strikes nationwide. Labor organizing and radicalism among the working class continued after 1886 too: there were about a thousand strikes per year in the 1890s and in 1904 there were a staggering four thousand strikes. Four hundred thousand miners went on strike in 1946; the Steel Strike of 1959 included a half a million workers and in 1970, 210,000 U.S. postal workers went on strike.

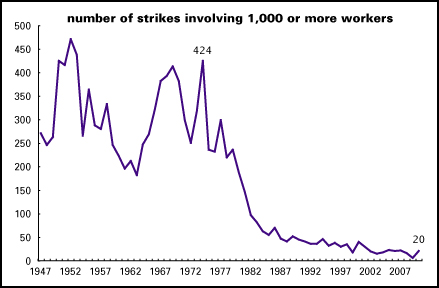

These are just a few examples. As the chart below demonstrates, the U.S. has a long tradition of labor unrest and it is only relatively recently that workers have not undertaken strikes as a method of resolving labor disputes and fighting for better living and working conditions.

There are historical reasons for the absence of work stoppages in the United States and one of them is the passage of laws restricting workers’ ability to strike. In New York, the Taylor Law, passed in 1967, punishes both public sector unions that strike as well as individual employees. This law was broken constantly in the early years of its existence, but it is now seen as a nearly insurmountable barrier to organizing a labor stoppage by public sector employees, who constitute the vast majority of organized workers in New York State.

In order to understand the Taylor Law, and particularly, the no-strike clause, it is critical to first understand the importance of strikes under capitalism, as a basis for understanding why it is so important for the state to curb them. With this understanding, this article will then analyze the historical context for the emergence of the Taylor Law.

Strikes are a School of War

Although he wrote over a 100 years ago, Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin’s analysis of strikes uncovers the reasons that strikes are so feared by the capitalist class. A strike involves workers withholding their labor as a tool for negotiating with the boss. In an arrangement where the boss makes all decisions about production — determines salaries, sets working hours, hires and fires workers, etc. — the only weapon that workers have in their arsenal is their ability to withhold their labor via the strike.

Yet, strikes can be much more than a bargaining chip — they are the way the working class learns its role in society. Strikes are a method for workers to shift from being passive victims of their circumstances to becoming political subjects. Lenin says, “When the workers state their demands jointly and refuse to submit to the money-bags, they cease to be slaves, they become human beings, they begin to demand that their labor should not only serve to enrich a handful of idlers, but should also enable those who work to live like human beings.”

Furthermore, strikes are one way the working class can begin to understand the nature of capitalism and the power that the working class has within it. Lenin goes on to say, “When the workers refuse to work, the entire machine threatens to stop. Every strike reminds the capitalists that it is the workers and not they who are the real masters — the workers who are more and more loudly proclaiming their rights.” The machine of society is moved by workers, not by the capitalists who exploit them. Every strike teaches the working class this very important fact.

The fact that strikes, particularly successful strikes, embolden the rest of the working class is expressed by several academics, even those who defend the Taylor Law. In the Michigan Law Review, the conservative Theodore Kheel says “The strike fever is contagious, and leapfrogging demands and multiplying disputes leave the government hesitant, defensive and distracted from the unresolved problems of our urban crisis” (Kheel 1969, 932). Lenin echoes this in his 1899 text, On Strikes.

Furthermore, in a strike, workers also understand that the function of the legal system and the class character of the state. Lenin says, “The workers begin to understand that laws are made in the interests of the rich alone; that government officials protect those interests; that the working people are gagged and not allowed to make known their needs; that the working class must win for itself the right to strike, the right to publish workers’ newspapers, the right to participate in a national assembly that enacts laws and supervises their fulfillment… Every strike strengthens and develops in the workers the understanding that the government is their enemy and that the working class must prepare itself to struggle against the government for the people’s rights.” The working class, when mobilized against the bosses, are repressed by the state. The government seeks to stop strikes by invoking the justice system and threatening workers with fines and even jail time. There is no mistaking whose side the government is on. The government seeks to stop strikes in order to maintain profit for the capitalists — or in the case of public sector employees, in order to keep the system running smoothly in order to ensure profits.

Although this is the potential work of a strike, that does not mean that all strikes do this. There are strikes that refuse to mobilize the rank and file, exerting some pressure on the bosses to gain minimal concessions. Strikes have the potential to be schools of war for the working class, but the union bureaucracy does everything possible to keep strikes from getting out of hand.

The reason that the government makes strikes illegal is not only to maintain capitalist profit. It is also because strikes reveal the truth of society to the working class and therefore, behind every combative strike lies the specter of revolution. Lenin says, “The government itself knows full well that strikes open the eyes of the workers and for this reason it has such a fear of strikes and does everything to stop them as quickly as possible. One German Minister of the Interior, one who was notorious for the persistent persecution of socialists and class-conscious workers, not without reason, stated before the people’s representatives: ‘Behind every strike lurks the hydra of revolution.’”

Before The Taylor Law: A Brief History

When World War II ended and profits for U.S. capitalists continued to skyrocket, the U.S. working class began to mobilize. In the first year after the end of World War II, one tenth of the nation’s workers went on strike, totaling 5 million strikers engaged in 4,630 work stoppages. All of the country’s basic industries were affected: coal, steel, auto and the railways. Even workers who were not organized into unions took part. For example, between 1920 and 1943, a total of 13 school districts went on strike. From February 1946 to May 1947, there were 29 strikes (Donovan 1990, 1).

In New York, for example, in May 1946, transportation workers, newspaper workers and other private employees went on strike against the firing of almost 500 workers and the move by the governor to privatize public-sector jobs. As a result, the governor was forced to recognize the right of public-sector workers to form unions (Donovan 1990, 3).

However, the government and the capitalists had learned from World War I, where a wave of worker mobilizations rocked the nation immediately after the war; in 1919, 4 million workers went on strike. After World War II, the government sought to curtail worker mobilizations, this time formally and by law. This meant the passage of the Taft Hartley Act in 1947.

Taft Hartley outlawed closed shop workplaces and required unions to give a 60-day advanced notification of a strike. It also authorized an 80-day federal injunction when a strike threatened to “imperil national health.” In other words, spontaneous strikes were outlawed and any strike that substantively shakes society in all of the ways Lenin described would be barred. The law prohibited sympathy boycotts, making it illegal for stronger unions to throw their weight and support behind smaller and weaker unions. It also narrowed the definition of unfair labor practices and required union officers to deny, under oath, any Communist affiliations. According to “Who Built America?,” “The law signaled a major shift in the tenor of class relations in the United States. To survive, the unions would have to function less as a social movement and more as interest groups protecting their own turf” (Brown, Clark et al 2008, 492).

The anti-communist clause and the attack on the right to strike should not be seen as separate entities. Organizing the working class and demonstrating its strength in strikes is an essential tool for communists. Unity of the working class against its capitalist enemies is an essential component of Marxist thought. Fostering yet another division and distrust among the working class is essential to demobilizing workers. As Who Built America? states, “ In conjunction with the anti-communist currents then sweeping the working class and stiffening the backs of employers, the anti-communist clause represented state action of a sort that opened the door to inter-union raiding and gave defenders of union political orthodoxy a new powerful weapon that decimated their opponents and weakened the idea of union solidarity” (Brown, Clark et al 2008, 501) The state was given a weapon to use against any kind of progressive union organizer, and the state fostered worker prejudice against socialism and socialists.

Also in 1947, New York State passed the Condon-Wadlin Act, which like Taft-Hartley, attacked labor organizing. It was brought about after public employees strikes in Rochester and Buffalo and the threat of a transit workers strike in New York City. The act made it illegal for state employees to go on strike; under this new law, strikers were fired. Workers could only be re-hired if they did not economically benefit from the strike. But, even in these cases, they would not be eligible for a raise for three years and would be placed on probation for five years.

However, the act was not enforced through most of its existence. In 1962, 2,000 motor vehicle operators engaged in a two-week strike that won a wage and benefit increase. In 1965, welfare workers went on strike for 28 days and despite the jailing of 19 labor leaders and the firing all of the strikers, the workers were re-hired and won pay benefits, the first 100 percent city-paid health insurance for civilian employees and the right to collective bargaining. There were 21 job actions that seemed like violations of the Condon-Wadlin Act, but the law was only invoked seven times. Only twice were strikers dismissed (Ronald 1990, 6).

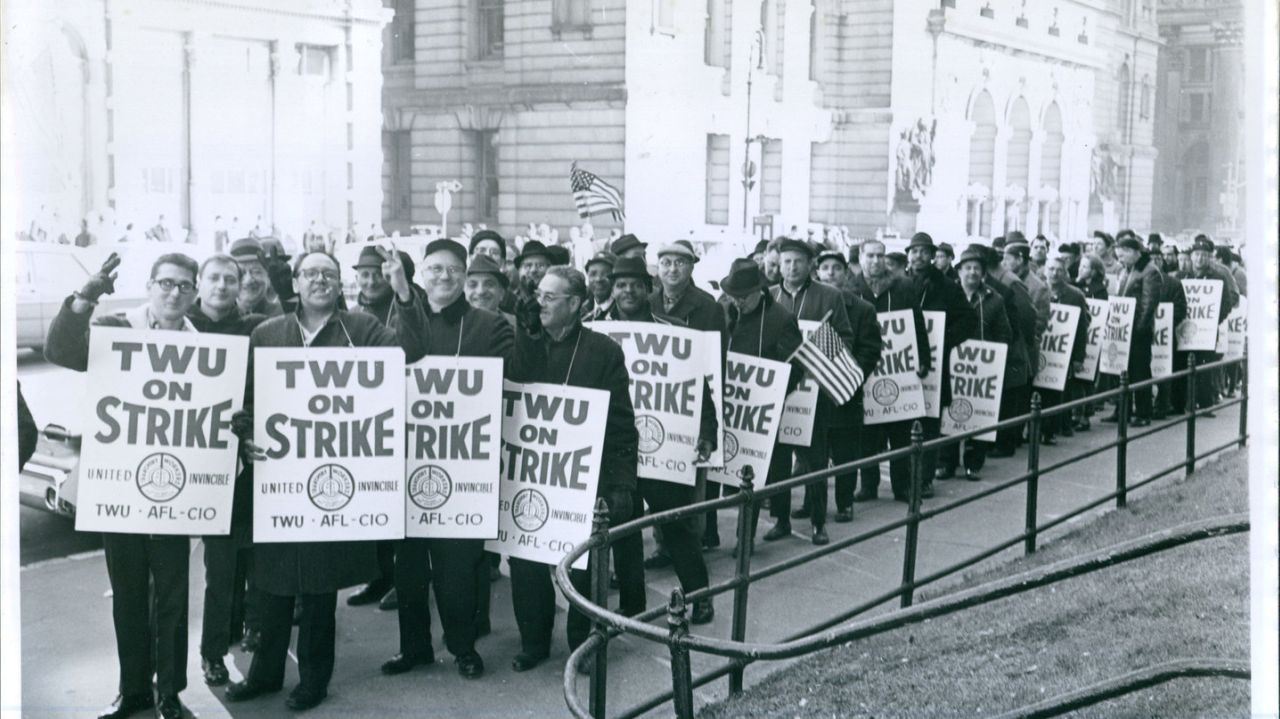

The transit workers strike of 1966 was the last straw. The 12-day strike brought New York City to a standstill and nine union leaders were jailed. Again, workers were not fired and won a pay increase as well as pension benefits. The wage increase was relatively minor. What was important about the strike is that the transit workers were prepared to go on another strike to defend themselves against the Condon-Wadlin penalties. “Not only had the law failed to stop the strike, but it threatened to produce a second work stoppage because of the penalty provisions… As a result, the governor and the legislature concluded that there was no alternative but to waive the penalties despite the clear violations of the statute. The law was in disrepute” (Kheel 1969, 933).

Image from AM New York

Ending Condon-Wadlin

After these strikes, it was clear that the Condon-Wadlin Act was not serving the government. Major strikes disrupted business as usual and the demonstrated the government’s inability to enforce the law against the working class. Clearly this could not stand. “A consensus rapidly emerged that penalties alone could not prevent public employee strikes and that some collective bargaining machinery was necessary to ensure labor peace” (Horton 1974, 163).

In 1966, Governor Nelson Rockefeller created the Committee on Public Employee relations that was meant to “make legislative proposals for protecting the public against the disruption of vital public services by illegal strikes, while at the same time protecting the rights of public employees” (Ronald 1990, 23). The chairman was George W. Taylor, a Professor of Industry at University of Pennsylvania. From this committee, what became known as the Taylor Law emerged.

The committee met privately and in informal meetings with interested parties. There was only one day of public hearings. While in public, the unions spoke out against the no-strike clause, in private they did not fight against it. In a memorandum, Victor Gotbaum of District Council 37 of AFSCME said “he wouldn’t be concerned with a statute barring strikes…” (Ronald, 1990 27 — based on memorandum of Corbin to committee in Cole papers.) There was some worker organizing against the law, reaching its zenith when the public employee unions organized a rally in Madison Square Garden denouncing the law.

Their efforts were not enough and most of the recommendations from Taylor’s committee were incorporated into state law in 1967.

The second article in this series explains the Taylor Law as well as its implementation.

Works Cited

Alvarado, Alfredo. “Strike Wave, Dramatic Growth, Huge Gains.” AFSCME District Council 37. N.p., n.d. Web.

Aronowitz, Stanley. The Death and Life of American Labor: Toward a New Worker’s Movement. London: Verso, 2015. Print.

Clark, Christopher, Joshua Brown, Roy Rosenzweig, Nancy Hewitt, and Nelson Lichtenstein. Who Built America?: Working People and the Nation’s History. Vol. 2. Boston, Mass.: Bedford/St. Martins, 2008. Print.

Freeman, Joshua B. “Anatomy Of A Strike.” New Labor Forum 15.3 (2006): 9-19. Web.

Helsby, Robert D., and Thomas E. Joyner. “Impact of the Taylor Law on Local Governments.” Proceedings of the Academy of Political Science 30.2 (1970): 29. Web.

Horton, Raymond D. “Public Employee Labor Relations under the Taylor Law.” Proceedings of the Academy of Political Science 31.3 (1974): 161. Web.

Kheel, Theodore W. “Strikes and Public Employment.” Michigan Law Review 67.5 (1969): 931. JSTOR [JSTOR]. Web.

Lenin, V.I. “Lenin: On Strikes.” Marxist Internet Archive. N.p., n.d. Web. 25 May 2017.