Monday, May 15 is the 75th anniversary of the Nakba. At the time of writing, the Zionist state of Israel is bombarding the Gaza Strip. Even amid the continued dispossession, displacement, and attacks, Palestinians are still fighting for their liberation. Around the world, massive demonstrations are taking place in solidarity with Palestine against the Zionist occupation.

The Nakba, or “catastrophe” in Arabic, refers to the process of ethnic cleansing that followed the establishment of the Zionist state of Israel in 1948. This included the forced displacement and dispossession of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians from their homes and their land.

Backed first by British and then later U.S. imperialism, Israel was created with the express purpose of serving these imperialist interests in the region. For decades, the U.S. has been Israel’s main source of support through military and economic aid, providing billions of dollars each year. Israel is now the most powerful military force in the region, serving reactionary causes all over the world, from the Chilean dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet in the 70’s to training US police today.

The Nakba was characterized by widespread brutality, including massacres, forced evictions, and destruction of homes and villages. It meant the destruction of thriving towns, the demolition of homes and the creation of Israeli settlements on the ashes. Many Palestinians were killed or fled their homes in fear of violence. In all, more than 750,000 Palestinians became refugees. Many were forced to live in precarious refugee camps in Palestine and surrounding countries, and their ancestors continue to live there today. Many Palestinian families still have the keys to their former homes.

While the Nakba marks a turning point in the history of the people of Palestine, the process of their displacement began many decades before, and is the product of a much broader process of global imperialist conflict in the early 20th century. The interests of British and U.S. imperialism, the Zionist project, and Arab bourgeois governments are all complicit in the ongoing oppression and displacement of Palestinian people today.

The British Mandate for Palestine

Throughout the 1800’s, Palestine was part of the vast Ottoman Empire, which included much of the Middle East, Southeastern Europe, and Northern Africa. Primarily agricultural, Palestine developed some thriving cities. As Sumaya Awad and Annie Levin write about Palestine before the Nakba:

“olive groves stretching across rolling hills dotting the land between mountains and the Meditarranean sea. Cafes and bakeries where Palestinians and people in transit from across the region filtered through on a daily basis on their way to school, a meeting or a doctor’s appointment with some of the finest physicians in the region. Each Palestinan city and town had an identity, a rich history and tradition, perhaps best reflected in unique tatreez patterns, or embroidery stitches attributed to different regions. Traditions of three different faiths existed side by side.”

Although it was mostly Arab, a small percentage of Jews and Christians lived in peace in Palestine. Arab nationalist movements were emerging against the Ottoman empire and historians such as Muhammad Muslih and Rashid Khalidi highlight the rise of Palestinian nationalism prior to the rise of Zionism, starting to see Palestine as a nation, or Palestine as part of a pan-Arab nation.

World War I reshaped the world map, including Palestine. This war was an imperialist war — a competition for markets, territories, and spheres of influence in the context of a crisis of capital accumulation and a world that colonial powers had divided up, organizing the world between imperialist powers and colonies. The war was centered on the control of international territory in the search for greater resources to boost these territories’ industries and thus gain new markets. The result of the war — a victory for the Allies, including the United Kingdom and France — reinforced the power and influence of the British in this area of the Middle East. The Ottoman Empire, which had previously controlled Palestine, sided with the Central Powers, who lost World War I.

The decline of the Ottoman Empire, dominant in the Middle East until the end of the 19th century, created the conditions for the developed capitalist powers of Britain and France to become hegemonic in the region. These two countries divided up the region in 1915 through the Sykes-Picot Treaty.

In 1917, in order to neutralize the Arab nationalist movements that had arisen against the oppression of the Ottoman Empire and to safeguard the imperialist British interests in the area (like control of the Suez Canal), Britain promoted the declaration of British Foreign Secretary Lord Balfour, who stated that he was in favor of the “creation of a Jewish national home” in Palestine. A colonial official explained the goal was “forming for England ‘a little loyal Jewish Ulster’ in a sea of potentially hostile Arabism.” Many antisemitic European leaders, however, also viewed the Zionist project of a Jewish homeland in historic Palestine as a way to rid Europe of its Jewish populations.

The declaration had a significant impact on the course of history in the region, leading to increased Jewish immigration to Palestine and laying the groundwork for the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948.

The Mandate for Palestine was officially created in 1922, following the granting of a mandate to Britain by the League of Nations — the imperialist predecessor of the United Nations — to administer the territory of Palestine. “Mandates” were simply a way to establish de facto colonies of Britain and France while claiming they were liberating colonies from other imperialist powers.

As described in the Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question:

The text of the Mandate reiterates Britain’s commitment to the Zionist project as phrased in the Balfour Declaration. It also decides that an ‘appropriate Jewish agency shall be recognized as a public body for the purpose of advising and cooperating’ with the Mandatory Power in matters related to the establishment of the Jewish National Home. It specifies that the Zionist Organization will be considered as such agency and requests it to secure the cooperation of all Jews who are willing to assist in the establishment of the Jewish National Home.

Under the British mandates, the British began to privilege the minority Jewish population over the majority Palestinian. By 1935, Zionists owned 872 out of 1212 industrial firms in Palestine, although they were still a minority of the population (Sumaya Awad and Annie Levin).

The increased influence of Zionists in Palestine was part of the reshuffling of imperialist powers after the war and reflected attempts by British imperialism to increase its wealth and power in the region. For the British who laid the foundations for the state of Israel, Zionism was not an ideological project, but was rather an imperialist project meant to enforce British wealth and power in the region.

The Origins Behind the Creation of the Zionist State of Israel

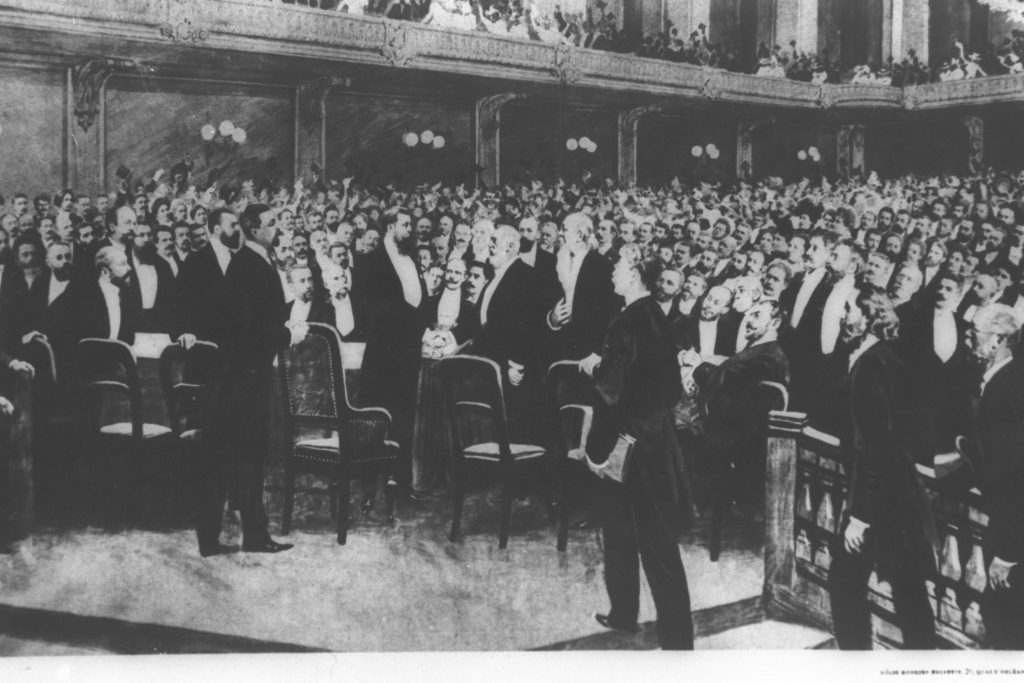

Zionism emerged in the late 19th century as a political and ideological movement among a small sector of the Jewish bourgeoisie. Their goal was to establish an exclusively Jewish homeland. While numerous locations were considered, including Argentina and South Africa, Palestine was chosen as the location for the founding of a Jewish nation. The movement gained momentum in the wake of a series of violent antisemitic incidents in the late 19th century, including the Dreyfus Affair in France and the pogroms in Tsarist Russia, but Zionists remained a minority among Jewish people. Rather than leave their home countries, many instead wished to stay to fight antisemitism.

As Mirta Pacheco explains,

At the end of the 19th century, [Jews] were forced to flee the pogroms in which they were murdered by the thousands, especially in Central and Eastern Europe, where bourgeois development was more backward, in contrast to Western Europe, whose bourgeois revolutions in England, France, and the Netherlands allowed the progressive integration and assimilation of Jews.

This backward Eastern European bourgeoisie confined Jews in those regions to misery and as a social force, pushed the Jews to proletarianization, misery and confined them to live in ghettos. They had become practically the last rung of their societies and that served the bourgeoisie to set them up as scapegoats for the sufferings of the masses.

This situation of persecution, oppression, and precarious living conditions, pushed large sectors of the Jewish community to lean towards socialist ideas and many joined socialist organizations with the aim of changing their living conditions and fighting against oppression. Major theorists of socialism have been Jewish, including Rosa Luxemburg and Leon Trotsky, who vehemently opposed Zionism. The Jewish Bund also organized Jewish socialists, also opposing Zionism. Chaim Weizmann, president of the World Zionist organization wrote “The lion’s share of the youth is anti-Zionist, not from an assimilationist point of view as in West Europe, but rather as a result of the revolutionary mood.. Almost the entire Jewish student body stands firmly behind the revolutionary camp.” (quoted in Sumaya Awad and Annie Levin).

Jewish Marxist Abraham Leon denounced Zionism “as a brake upon the revolutionary activity of the Jewish workers throughout the world, as a brake upon the liberation of Palestine from the yoke of English imperialism, as an obstacle to the complete unity of Jewish and Arab workers in Palestine.” Proponents of Zionism sought the support of European leaders making precisely this argument– that Zionism would solve the “problem” of Jewish people turning to socialism. Winston Churchill himself wrote an article entitled “Zionism versus Bolshevism,” calling for a Jewish movement that would lead Jewish people away from socialism.

While Jewish people wanted to live free from persecution and discrimination, the founders and subsequent leaders of Zionism had their own political goals and didn’t hesitate to make alliances with anti-Jewish political leaders. There are countless examples of this.

Theodor Herzl, one of the founders of Zionism, saw the deeply anti-Jewish Tsarist regime as a potential ally to create Israel. As writer Lenni Brenner explains:

Herzl looked elsewhere, even turning to the tsarist regime for support. In Russia Zionism had first been tolerated; emigration was what was wanted. For a time Sergei Zubatov, chief of the Moscow detective bureau, had developed a strategy of secretly dividing the Tsar’s opponents Because of their double oppression, the Jewish workers had produced Russia’s first mass socialist organisation, the General Jewish Workers League, the Bund.

This brought Herzl to St Petersburg for meetings with Count Sergei Witte, the Finance Minister, and Vyacheslav von Plevhe, the Minister of the Interior. It was von Plevhe who had organised the first pogrom in twenty years, at Kishenev in Bessarabia on Easter 1903. Forty-five people died and over a thousand were injured; Kishenev produced dread and rage among Jews.

Zionism cannot be separated from colonial and racist ideologies as well. Theodor Herzl also argued in his book The Jewish State that the Jewish colonization of Palestine represented the European advance embodied as “an outpost of civilization as opposed to barbarism” of the Arab peoples.

One of the most well-known examples of this type of alliance was the Haavara Agreement, which was signed in 1933 between the Zionist Federation of Germany and the Nazi government. It allowed Jewish people to transfer some of their assets out of Germany in the form of German goods, which were then sold in Palestine. The proceeds from the sales were used to finance Jewish settlement in the territory. With this agreement, the Zionists carried out the disgraceful policy of breaking the international boycott against Nazi Germany.

The creation of Israel was never about providing a safe homeland for Jewish people, but rather serving the interest of the bourgeois sector of the European Jewish community. In 1938, David Ben-Gurion, who was to become the first prime minister of Israel, wrote: “If I knew that it would be possible to save all the children in Germany by bringing them over to England, and only half of them by transporting them to Eretz Yisrael, then I would opt for the second alternative.”

Further and perhaps more insidiously, Zionism was an attempt to divert European Jewish workers and youth away from the process of class struggle and into a colonial project in Palestine. This became even more important for the European bourgeoisie after the 1917 Russian Revolution, which overthrew capitalism in Russia, led by none other than Leon Trotsky, who was Jewish.

The Jewish Community in Europe and in Palestine

Throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Jewish people in Europe faced increasing antisemitism. This included discriminatory laws and violent pogroms across Tsarist Russia, Poland, and Germany, among other countries. In the context of economic crisis and increased capitalist tensions, Jewish people served the role of scapegoat for the European bourgeoisie.

These attacks on Jewish people were exacerbated by the rise of antisemitic political movements like fascism in the lead up to the Second World War. Between 1941 and 1945, the Nazis carried out one of the most abhorrent events of human history: the Holocaust, which included the dispossession, persecution, and extermination of 6 million Jewish people in concentration camps, as well as numerous LGBTQ+ people, people with disabilities, and Roma people.

Britain, the United States, and Zionists used this persecution and suffering of the Jewish people for their own purposes and to encourage migration towards Palestine.

Contrary to popular belief, the conflict between Jews and Muslim Arabs is not inherently a religious conflict. In fact, at the beginning of the 20th century, Palestinian workers welcomed Jewish people, and before the founding of the State of Israel, they coexisted peacefully in Palestine. There were even examples of class solidarity, in which Jews and Palestinians created strong alliances against their oppressors and exploiters.

Socialist Simone Ishibashi describes that:

During the centuries of Moorish domination of Andalusia, in the Spanish Empire, Arabs and Jews lived together in peace. After the Inquisition, Sephardic Jews were received by the Ottoman Empire in Egypt, North Africa, and for 500 years they lived peacefully alongside Turkmen and Christian Arabs. At the beginning of the 20th century, in Palestine, Jews constituted a minority of 5% of the population integrated into a predominantly Arab society, with full freedom of worship.

As Miguel Raider explains:

Concentrated in ports, communications, railroads, metallurgies, oil refineries and large bakeries, hundreds of thousands of Arab and Jewish workers performed common tasks. This working class resided in the two great urban centers: Jaffa (the founding neighborhood of the future Tel Aviv) and Haifa, the main port and industrial center. The relations of solidarity between Arabs and Jews were expressed in the bakers’ union, declared to be of ‘international character’ and ‘open to all workers’.

In the 20’s, there were examples of unified actions of Arab and Jewish workers. In 1922, the Union of Railway, Postal, and Telegraph Workers formed, which unified Arab and Jewish workers. In 1931, there was a 10 day strike of Arab and Jewish workers protesting taxes on gasoline. However, Zionist union leadership has actively worked at every turn to deter any unity of Jewish and Arab workers. Miguel Raider goes on to explain

David Ben Gurion, leader of the Histadrut (the Zionist labor center) and future head of the State of Israel, maintained that Jewish workers should be organized in unions ‘linked’ although ‘separated’ from the Arabs, according to ‘national sections’. Jaim Arlozoroff developed this orientation by assimilating the experience of South Africa, where the most qualified tasks were reserved for whites, organized in unions separated from blacks. Thus, the Histadrut ended up expelling the communist militants of Jewish origin who fought for common unions.

The Zionist workers’ center put all its efforts into breaking strikes carried out jointly by Arabs and Jews, such as the conflict of April and May 1933 in the Nesher quarry. Under the slogan of kibush haavoda (conquest of work), the Histadrut concluded agreements with the employers to substitute the Arab labor force, in exchange for labor discipline. As a result of this racist and pro-employer policy, PAWS emerged, the first Palestinian workers’ union based in Haifa, Jaffa and Jerusalem, which stood for unity, against Zionism and Palestinian independence.

The period between 1929-1939, when persecution against Jewish people in Nazi Germany and Europe was increasing significantly, marked the fifth wave of Jewish migration to Palestine. During this decade over 230,000 Jews immigrated to Palestine, making it the largest wave before the Nakba.

Meanwhile, the U.S. and European countries denied asylum to hundreds of thousands of Jewish refugees. One example from the U.S. is the case of the St. Louis, a ship that carried 937 passengers, almost all of them Jewish refugees from Germany. They were turned away at U.S. shores and 250 were killed once they came back to Europe.

Another example is the Wagner-Rogers Bill, a 1939 proposal in the U.S. Congress that would have admitted 20,000 Jewish refugee children from Germany over two years. But the bill was opposed by anti-immigration and anti-semitic groups, and never passed.

By contrast, Trotskyists of that era were campaigning to let them all in. The Socialist Workers Party (SWP) advocated for the admission of Jewish refugees and actively campaigned against the U.S. government’s restrictive immigration policies. In their publication Socialist Appeal, the main headline in November 1938 was “Let the Refugees into the U.S.! – Open the Doors to Victims of Hitler’s Nazi Terror!”

At the same time, the so-called “left-wing” Zionists set up “socialist” colonies (the so-called kibbutzim) in Palestine, which in fact were military camps that interfered with communications between the Palestinian villages.

A Fierce Palestinian Resistance

Throughout the 1920’s and 1930’s, a fierce Palestinian resistance formed against British colonialism and Zionist incursions in Palestine. In 1929, Palestinians organized the Buraq Rebellion against new incursions by Zionist settlements, which was repressed by the British army.

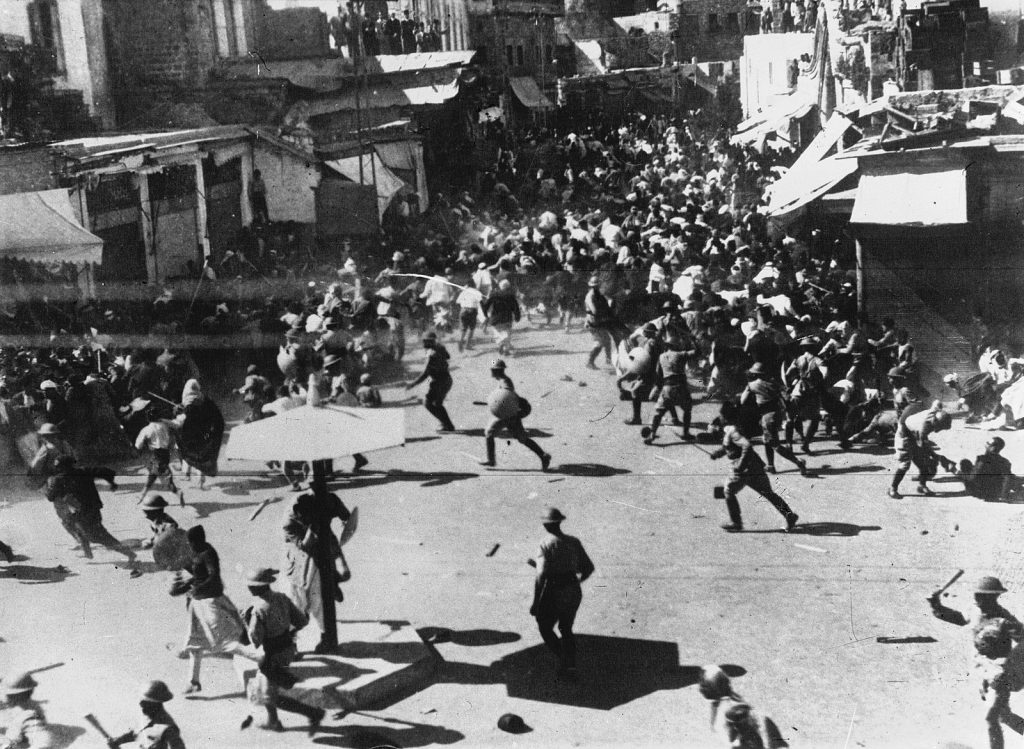

In October of 1933, a general strike in Palestine took place in protest of the growing Jewish immigration and British policies favoring land acquisition by Jewish settlers. The British Mandate authorities declared the strike illegal, and deployed troops to end the rebellion. Over the course of the strike, more than 30 Palestinians were killed by live ammunition and 200 were injured.

While the Palestinian political leaders ended the strike, the main issues remained unresolved and tensions escalated. In 1935, a shipment of arms destined for the Haganah was discovered by Arab dock workers. The Haganah was a Zionist paramilitary organization that had existed in Palestine since 1920, working closely with British colonial authorities and carrying out clandestine operations, including smuggling in weapons. This deepened the Palestinians’ concerns that the Zionists were getting ready to advance in their project of building their own state and expelling the Palestinian population.

The Arab revolt began in April 1936 with a general strike and acts of civil disobedience, and quickly escalated into violent repression of the British security forces and Zionists.

As historian Alex Winder explains:

The strike was widely observed and brought commercial and economic activity in the Palestinian sector to a standstill. Meanwhile, Palestinians throughout the countryside came together in armed groups to attack—at first sporadically, but with increasing organization— British and Zionist targets. Some Arab volunteers joined the rebels from outside Palestine, though their numbers remained small in this period. The British employed various tactics in an attempt to break the strike and to quell the rural insurrection. The ranks of British and Jewish policemen swelled and Palestinians were subjected to house searches, night raids, beatings, imprisonment, torture, and deportation. Large areas of Jaffa’s Old City were demolished and the British called in military reinforcements.

The British responded with a massive military crackdown, deploying tens of thousands of troops, tanks, warplanes, and heavy artillery. During the three years of the revolt, around 5,000 Palestinians were killed and nearly 15,000 wounded. To bring some stability to the region, the British wrote the White Paper of 1939, which stated that the British government intended to establish an independent Palestinian state within 10 years, conditional on safeguarding “the special position in Palestine of the Jewish National Home,” with a limit on Jewish immigration and land purchases in the meantime.

However, this was far from a real solution for Palestinians. The British Mandate had been collaborating with the Zionists from day one, and was responsible for their advance against the Palestinian population. Now, Palestinian resistance forced the British to change their strategy, which resulted in Zionist backlash against the British Mandate as well as Palestinian civilians. The deteriorating British hegemony in the region paved the way for the creation and strengthening of Zionist paramilitary organizations that enacted more terror on Palestinians.

Among these was Irgun, which launched a wave of attacks against Palestinians mainly in Haifa and Jerusalem, including bombs, killing dozens of Palestinians and wounding hundreds. The Irgun was formed in 1931 and it was led by Menachem Begin, who later became Prime Minister of Israel. Since then, the tensions between the British Mandate, the Zionist and Palestinians only deepened.

It is important to note that the vanguard of the numerous uprisings against Zionism and the British mandate were working class and peasant Palestinians. The elite and emerging bourgeoisie in Palestine, while opposing British colonialism and Zionism, played a role as a brake on the anti-Zionist struggle. As Mostafa Omar explains, wealthy Palestinian families often competed for support from British authority. Further, they had ties to the pro-British Arab ruling class, which made the Palestinian elite play a conservative role in the struggles of Palestinian workers and peasants against colonialism. As Mostafa explains, “The Palestinian elite were more interested in maintaining its wealth and its ties with Arab regimes than it was in leading the fight against British colonialism and Zionism. In contrast, throughout the same period, Palestinian workers and peasants made enormous sacrifices in the nationalist struggle. In the cities, workers organized numerous strikes and street protests. In the countryside, peasants fought bravely despite years of British terror.”

The defeat of the uprisings in Palestine in the 30’s set the stage for the Nakba.

The Nakba

In December 1947, Palestinians constituted two thirds of the total population of Palestine. The other third were Jewish settlers, most of whom had arrived after 1920. Of the total cultivated land, most belonged to the native population and only 5.8 percent was in the hands of Jewish settlers. Most Jewish people had settled in the cities, and there were isolated Jewish colonies in the countryside.

As the end of the British Mandate approached, the United Nations put forward a Partition Plan for Palestine, which was adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1947 as Resolution 181. In doing so, the United Nations was ready to hand over more than half of the Palestinian territory to the Zionists to create their new colonial state — without considering in the least the interests of the Palestinian population, who opposed the partition.

Palestinians rightfully refused to accept the plan, and on May 15, 1948, a day after the Zionist State was declared, a general strike took place across the country in opposition to this attack on Palestinian self-determination. But the strike was met with strong violence from Zionists, who imposed curfews and carried out political persecution and assassinations against resistance leaders. Palestinians also organized military defense at local levels, but they were defeated by Zionist forces which were armed with more advanced weaponry and trained mainly by British imperialism. The support from other Arab and Muslim countries was not coordinated enough to provide a stronger resistance. The occupation army was able to advance in Palestinian territory through blood and fire.

According to research by Salman Abu Sitta published in The Atlas of Palestine, an estimated 700,000 to 800,000 Palestinians out of a population of 1.9 million were displaced during the Nakba. Many were forced to flee their homes due to violence and intimidation, while others were expelled by Israeli forces. An estimated 15,000 Palestinians were killed.

The Nakba created one of the largest refugee populations in the world. Today, there are an estimated 5.7 million Palestinian refugees, including those who were displaced during the Nakba, as well as their descendants.

Over 500 Palestinian villages were depopulated or destroyed during the Zionist offensive. Many of them were sites of open massacres, like in Baldat al-Sheikh (1947), al Khisas (1947), al-Abbasiya (1948), Lyyda (1948), Deir Yassin (1948), among others. The latter involved the killing of over 100 Palestinian villagers, including men, women, and children by Zionist paramilitary forces from the Irgun and Stern gangs (also known as Lehi).

The attack in Deir Yassin began in the early hours of the morning, when Irgun and Stern members entered the village and began shooting indiscriminately at the villagers. Many were killed in their homes, while others were shot while trying to flee. The attackers also reportedly used grenades and machine guns to kill as many people as possible. This attack had a menacing impact on the surrounding Palestinian villages, prompting many people to flee their homes in fear of similar attacks.

Menachem Begin expressed in his memoirs that without what was done in Deir Yassin, there wouldn’t have been an Israel. After that massacre, according to him the Zionists were able to “advance like a hot knife through butter.”

Communists and the Creation of Israel

The first country to recognize the creation of Israel in 1948 was the United States on May 14, just hours after Israel declared “independence.” A few days later, on May 17, the bureaucratized Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin also recognized the Zionist State after initially expressing support for the creation of a Jewish state. The following day, May 18, Czechoslovakia, which was already part of the Soviet Bloc, added its recognition and later sent weapons to the Zionists.

This tremendous betrayal by supposed “communists” is yet another powerful example of the degree to which the Soviet Union had degenerated into a bureaucratized workers state, one driven primarily by maneuvers to maintain what Stalin called “socialism in one country.” Rather than seeking to expand the revolution, Stalin attempted to make agreements with imperialist powers. Leon Trotsky, the leader of the Left Opposition, and later the Fourth International, sought to maintain the threads of continuity of the revolutionary movement by standing for internationalism, class independence and global socialist revolution.

As a result of the Stalinist support to creation of Israel, writer Nathaniel Flakin points out:

the ideas of socialism and communism, which once had great appeal to the Arab masses, were discredited across the region. In the United States, the official communists were already used to accepting sudden zig zags in their political line. Within a few months, the CPUSA was offering unqualified support to the Zionists’ ethnic cleansing and spreading false reports about supposed Arab atrocities in order to justify it.

…

Genuine communists — those opposed to Stalinism — always rejected Zionism. While Stalin’s bureaucracy was busy making deals with imperialist powers — first with the Nazis, then with the “democratic” imperialists — it was the Left Opposition led by Leon Trotsky that fought for the political independence of the working class. This meant opposing any form of imperialism and colonialism, including Zionism.

A small Trotskyist group existed in Palestine at the time called the Revolutionary Communist League– a break with the Stalinist Communist Party. Made up mostly of Jewish people, it spoke directly to Jewish workers, many rightfully fearful for their safety in the aftermath of the Holocaust, explaining that the creation of the Jewish Israeli state would be a tool of imperialism. In their declaration following the 1948 creation of Israel, they wrote,

In order to solve the Jewish problem, in order to free ourselves from the burden of imperialism, there is only one way: the common class war with our Arab brothers; a war which is an inseparable link of the anti-imperialist war of the oppressed masses in all the Arab East and the entire world.

The force of imperialism lies in partition – our force in international class unity.

Arab Governments and the Zionist State.

While the governments of the Arab League were against the creation of the Zionist State, there were occasions where their leaders tried to negotiate with them or didn’t rally united behind the Palestinians’ interests. That tension is even stronger today, as more Arab countries are establishing diplomatic relationships with Israel.

As Mirta Pacheco explains,

This policy of beginning to occupy lands that did not originally belong to them, constituted the great agreement between Zionism and the imperialist powers, specifically in this case Britain, but had the complicity of members of ‘royal’ Arab families, as is the case of Faisal Husain, a member of the Hashemite family. (…)

Husain was a nationalist leader of the Arab rebellion (1916/1920) against the Ottoman Empire and whose project was an Arab state, founded on the basis of a constitutional monarchy in the territories known at that time as Syria, which included present-day Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, the State of Israel and the occupied territories. As this project clashed with the aspirations of the imperialist powers for the distribution of markets, Faisal was confronted with France, which for that imperialist distribution possessed Northern Syria (Lebanon and Syria), he was expelled from Syria by the French who unleashed a bloodbath in that area, that made him turn to agreements with Britain and Zionism, since he was the visible face of the Arab monarchy that also claimed for itself the lands of Palestine.

In 1919 Faisal signed an agreement with Zionism represented by its leader Jaim Weizmann, where he recognized their right to mass immigration to Palestinian lands, simply in exchange for religious equality and Muslim control over the holy places of Islam and to promote the constitution of an Arab state that excluded Palestine.

However, the Faisal-Weizmann Agreement was never implemented due to political opposition from other Arab leaders and resistance from the British. A few months later, Zionism took advantage of the Paris Conference (the meeting where the Allies discussed the conditions to be imposed on the defeated countries of World War I) and Husain abandoned this strategy.

Later on, closer to the Nakba, the Arab League was divided in two sectors: a Hashemite bloc consisting of Transjordan and Iraq, and an anti-Hashemite bloc led by Egypt and Saudi Arabia. Neither sector had a solid and strong stance toward defending Palestine. Rather, they had their own political goals. For example, Jordanian King Abdullah bin Hussein had his own ambition of becoming the leader of a Greater Syria, which included Transjordan, Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine, threatening these countries’ independence.

In 1979, Egypt became the first Arab country to sign a peace treaty with Israel, known as the Camp David Accords. In 1994, Jordan signed a peace treaty with Israel, normalizing relations between the two countries. Six years later, in 2020, the UAE and Bahrain signed the Abraham Accords and Morocco normalized relations with Israel in exchange for long-sought U.S. recognition of its claims on Western Sahara. These diplomatic and commercial relationships between Arab nations and Israel have created strong discontent among the population of these countries.

This period of history also holds important lessons for socialists. The capitalist leaders of Arab nations are primarily concerned with holding onto their own power and expanding the interests of the capitalists in their region. While that may put them in momentary conflicts with U.S. and Western imperialism, it has meant usually not taking up the Palestinian cause or using it as a bargaining chip. The answers to the struggle for Palestinian liberation lie not with Arab bourgeois governments, but with the Arab working class.

75 Years After Nakba

The Nakba is not merely a historical event. It is not in the past — the catastrophe is ongoing. Using U.S. funding, Israel is now a monstrous settler-colonial apartheid state that continues the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians. The violence and dispossession against Palestinians are constant.

Since the week prior to this year’s Nakba anniversary, the Zionist State of Israel has been attacking Gaza in an operation dubbed “Shield and Arrow” with the supposed goal of assassinating senior commanders of the second largest armed group in the coastal region, Islamic Jihad. But the attacks were far from hitting military targets: they destroyed over 15 homes, damaged over 900 houses, damaged other civilian structures, and killed at least 5 children and 31 other Palestinians.

Today, more than two million Palestinians are crowded into the Gaza Strip, one of the most densely populated areas in the world. It has been under blockade by Israel since 2006 and is the world’s largest open-air prison.

According to an Amnesty International report, there are over 600,000 Jewish Israeli settlers living on occupied Palestinian land. Those settlements are surrounded by walls, control towers, and a perpetual military presence. In the West Bank, this is a constant threat to Palestinians’ lives and livelihood, not only because of the violence, harassment, and isolation from other Palestinian cities, but also because these zones are used as trenches to expand the dispossession, displacement, and killing of Palestinians.

Jerusalem, a city of religious significance to Jewish, Muslim, and Christian people alike, continues to be a zone of intense repression for Palestinians. Though Jerusalem has long been the capital of Palestine, the Zionist regime, with the support of U.S. imperialism, has claimed the city as its own capital. In Jerusalem and its surroundings, Palestinians suffer constant evictions and house demolitions, military harassment, and constant and increasing violence in the Al-Aqsa Mosque. Even Palestinian schools and education are under attack. The U.S. continues to contribute billions of dollars annually to arm the occupation forces to the teeth against Palestinian, as well as against other U.S. rivals in the Middle East.

In 2021, the occupation forces launched an eleven-day war against Gaza. It resulted in the deaths of over 250 Palestinians, including more than 60 children and 12 Israelis. Many buildings and infrastructure in Gaza were destroyed or severely damaged during the conflict. This offensive sparked a massive international movement in solidarity with Palestine. Recently, Israel has been wracked with political turmoil– corruption charges against Netenyahu and now the inability to form a government in Israel. Israel has been immersed in massive protests against the new far-right government and their attacks against the judiciary system and democratic rights of Israelis. All of this inner turmoil in Israel has not provided a left wing response; in fact, Israel is moving further and further to the right, with Netenyahu expanding settlements and violence against Palestinians with essentially no opposition. Liberal Zionism, if there ever was such a thing, is seemingly dead.

Recently, Israel has been immersed in massive protests against the new far-right government and their attacks against the judiciary system and democratic rights of Israelis. But, as Illan Pappé puts it,

their liberal Zionism is founded on a series of oxymorons: Israel as an enlightened occupier, a benevolent ethnic cleanser, a progressive apartheid state. Thanks to Netanyahu’s government, this image is now under threat; its contradictions are no longer containable. The state’s reputation is being damaged not only domestically, but also among the ‘international community’ that typically hails Israel as the only democracy in the Middle East and Tel Aviv as the LGBT capital of the world, while ignoring the besieged Gaza ghetto a few miles south.

This crisis in which Israelis are denouncing the lack of democracy in Israel also opens the question: democracy for whom? Any serious questioning has to include the end of the Palestinian occupation and the Zionist state.

For a Free and Socialist Palestine

The Zionist state of Israel is a completely reactionary entity, from its foundations tied up in maintaining profits for western imperialism. A true peace, and a state where Arabs and Jewish people can coexist in full equality, will not be possible as long as a Zionist State exists. This state, an arm of imperialism, is based on colonization and national oppression, whose constitutive principle is the exclusionary Jewish character of the state. For this very reason, this state is completely incompatible with the Palestinian people’s right to national self-determination. As long as Israel exists, there will be no Palestinian liberation.

As explained, in order to think of Palestinian liberation, we cannot look to the Arab bourgeoisies, like many petty bourgeois leaderships in Palestine, including Hamas, do. Israel is primarily a creation of imperialism and of capitalism. The way to fight it must include the struggle of the Arab working class, which have initiated strikes and taken the streets in numerous uprisings. While the Israeli working class is predominantly reactionary and Zionist, a socialist perspective means fighting for a sector of that working class to break with Zionism and join the struggle for a free Palestine. And the workers of the world, especially in the United States have a role to play in stopping arms shipments to Israel and demanding an end of U.S. aid to Israel. This movement, led by the working class, is the only force that can free Palestine. And as Trotsky’s theory of the permanent revolution highlights, achieving national liberation will mean confronting capitalists interests in Israel and in the region. The task of national liberation is intimately linked to the task of expropriating the capitalist interests that are tied to Western imperialism and to Israeli capitalism.

A State that shelters working people, regardless of whether they profess the Muslim, Jewish, Christian, or no religion — as they did for centuries before the imperialist offensive — will only be possible through a workers’ and socialist Palestine that embraces all its historical territory, defending the need for a Federation of Workers’ Republics of the Middle East. This is a task to be undertaken by the working class, poor, and oppressed of the whole region and the world.

¡Viva Palestina Libre!