Today, in 1925, a group of porters launched the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP). After a number of attempts to organize, these workers finally succeeded in winning union recognition and a union contract. They also won an international charter from the American Federation of Labor (AFL) which was a fight in itself to combat the racism within organized labor. All this would take over twelve years of struggle. But the history of one of the most influential Black unions — and of its leader A. Philip Randolph — is not simply one of heroic workers defeating the powerful Pullman Car Company, but one filled with lessons on class struggle.

Three Porters Meet With the “Lenin of Harlem”

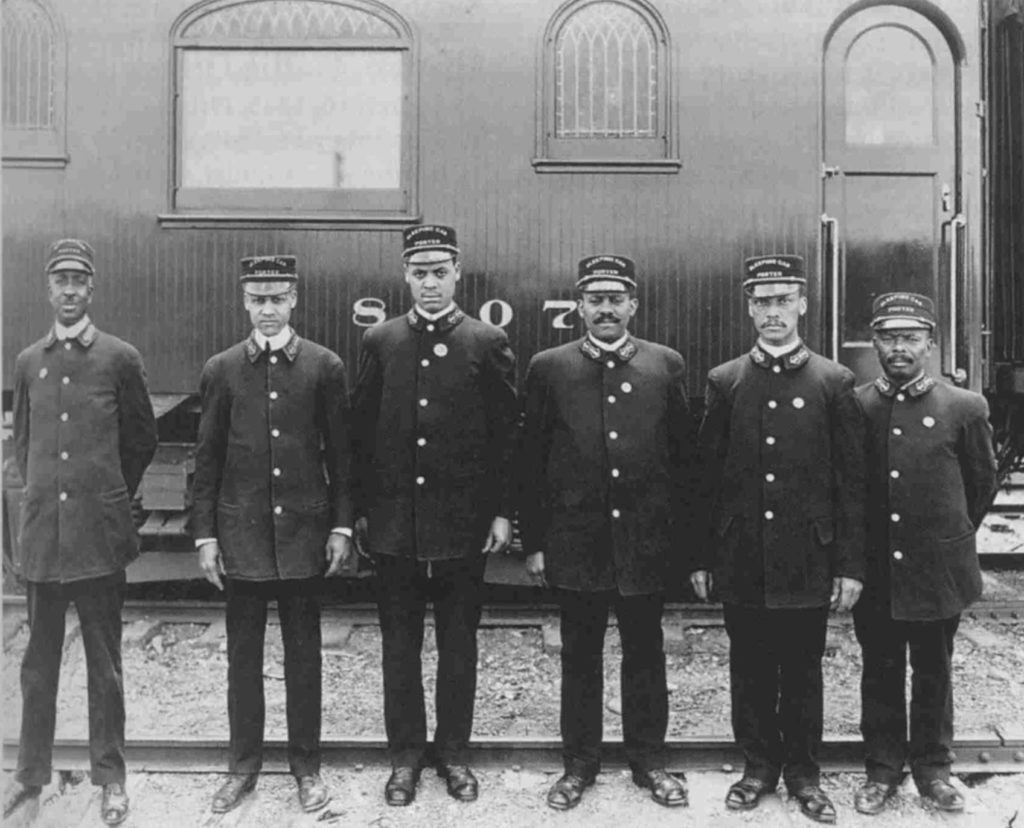

In August 1925, three Pullman porters — Ashley Totten, W.H. Des Verney, and Roy Lancaster — approached Asa Philip Randolph with the proposition to help them organize a union for the porters. Labeled the “most dangerous Negro in America” by Attorney General Alexander Palmer in 1919, Randolph was the firebrand co-founder of what he called the “only magazine of scientific radicalism in the world, published by Negroes,” The Messenger. With a circulation of up to 26,000 copies, the magazine was mainstay on the left, and within the milieu of the Harlem Renaissance. With the magazine, and experience in organizing elevator operators, Randolph was the natural choice for the porters. They were also looking for a leader not employed by Pullman since attempts to organize floundered over the years because of firings and the use of stool pigeons. From Des Verney’s house, they started to plan.

On August 25, the first meeting was held and 500 porters plus Randolph launched the campaign. Randolph put The Messenger to work by publishing the “Case of the Pullman Porter” which painted the exploitation and humiliation porters faced on the job in vivid detail and ended with the demands of the porters. Delivering the porters’ experience to a broad audience, the article explained how they worked exhausting routes with little sleep for a paltry wage and how 400 hour months for around $70 was the norm. They earned a few tips here and there from travelers who called them George, hearkening back to the custom of calling slaves by the name of their masters, in this case, George Pullman. Like slaves too, the hours they prepared the sleeper cars were unpaid labor, and on top of that, they had to pay for their own meals and replace towels and toiletries that were stolen by passengers. And so, the porters demanded a living wage, paid preparation time, equal pay with white conductors if they were assigned to do conductor’s work and an opportunity for promotion to conductor, a 240 hour month, guaranteed time to sleep, and the right to organize.

With the press, and skilled organizers like Milton P. Webster in Chicago, the newborn Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) spread quickly through the train routes. At the transportation hubs of the country, like in Chicago, New York, and St. Louis, meetings brought in hundreds of porters. The BSCP was off to a good start.

Pullman Retaliates

At first, the Pullman company ignored the latest campaign since they had precautions in place to limit the effectiveness of union drives, one of which was their profile in the Black community. By 1925, the company was the largest private employer of Black workers, and the jobs were seen as marginally better than farm labor and other sectors that did not discriminate. Understanding this, the company established good relations with parts of the Black bourgeoisie, in churches, and with the Black press, notably with the Chicago Whip and the Chicago Defender. These newspapers would come to support the incipient union, albeit with reformist reservations.

The company had previously founded yellow unions such as the Pullman Porters Benefit Association (PBA) and the Employee Representation Plan (ERA) to forestall organizing. Here, they were encouraged to set up company unions by the post-World War I federal government that preferred arbitration and collaboration to strikes and conflict. These organizations, funded and supervised by the company, were shams to every porter, including Totten and Lancaster who themselves were officials of the PBA and the ERA.

The third component of the Pullman anti-union strategy was the utilization of spies to root out militants and sow confusion. Previously all this was enough to put down attempts at unionization. But, when these measures failed and by late 1926 half of the 12,000 porters belonged to the BSCP, the company went on the offensive with mass firings.

The crackdown, as well as the tribune of The Messenger, brought allies to the BSCP in the form of the NAACP, the Urban League, and other liberal circles. Wives and girlfriends of porters started the Economic Council of Women as an auxiliary to support the BSCP. Conferences, speaking tours, and fundraisers were used to build the cause into a hegemony in the workers’ movement and the Black community. Though attacked, their numbers grew.

The AFL, the BSCP, and the Federal Government

While the BSCP was in struggle with the Pullman company, in 1926, Randolph made his first bid to win an international charter from the American Federation of Labor, which was then under the leadership of a new president, William Green. The Executive Council initially postponed the application to conference on jurisdiction questions of the Brotherhood, since both the hotel workers’ union and the bartenders’ union claimed Pullman cars as “hotels on wheels.” In the end the BSCP’s charter was rejected in favor of the various locals throughout the country joining the AFL labor councils as federated units. This would have split up the BSCP locals and allowed it to be subsumed into numerous unions. This “compromise” was rejected and the AFL continued to refer to this plan against years of attempts to join the AFL as a whole.

To understand why the AFL refused to grant the charter to Black workers requires a brief note on the political battles within the union movement. Whereas some of the early union federations, most notably the Knights of Labor, were committed to organizing all workers and did practice racial integration in some assemblies, they also tolerated segregation at the discretion of the local unions so as to not offend some affiliates. The “unity” of the movement based on accommodating prejudice was more important than the hard political fight required to build the real unity of workers, Black and white. This commitment also did not extend to immigrant workers, and the Knights of Labor was not alone in supporting the Chinese Exclusion Act.

At the founding of the AFL in 1881, president Gompers asserted that the federation does “not want to exclude any working man who believes in and belongs to organized labor.” And for some years the AFL exhorted affiliated unions to organize Black workers. However, by 1895, the railroad unions had begun to implement discrimination in their constitutions against Black workers. Like in the Knight of Labor, not wanting to lose such an important constituency, the AFL reneged on its earlier spirit. After 1900, membership requirements were entirely in the hands of affiliated unions and the compromise was a kind of “separate but equal” practice by which separate charters were allowed for unions “composed exclusively of colored workers.” This was the go-ahead to exclude Black workers. The Order of Sleeping Car Conductors itself — a Pullman rail white union — even used this reasoning to justify their neglect of the Pullman porters for years.

The AFL did donate funds to the Brotherhood, and Randolph, who believed that the BSCP could be a spearhead for Black workers into the labor movement, continued to list the AFL and the railroad unions as “moral support” in the press.

A relationship with the main union federation in the country had advantages outside of being financial and moral support. In May of that year, the Railway Labor Act was passed. The law ostensibly protected railroad workers from forming independent unions, outlawed company unions, and set the rules around elections for recognition. Randolph believed that the AFL international charter would assist the Brotherhood’s petition for an election. With or without that charter, after two years of deliberation, the mediation board established by the law sided with the company.

A Strike is Planned

In March, 1928, following the “adverse decision from the ICC,” Milton P. Webster, who by this time had been elected as the Vice-President of the BSCP, noted in a letter to Randolph the “high spirit” of the workers and the need to strike “while the iron is hot.” A strike vote was held and the result was 6,053 in favor, and 17 against — an overwhelming mandate. But, on the night before the strike was to begin, Randolph, in consultation with President Green of the AFL, called off the strike. He was convinced that further mediation would produce a different result and wanted to maintain good relations with the AFL leadership. Randolph then went after disappointed rank and filers — who he believed were Communist Party agitators — claiming that the strike was only postponed and that the BSCP had “undoubtedly got the Pullman Company licked” in the field of public opinion. The membership did not buy it, and by 1933, only 500 porters were enrolled in the union. By sacrificing militancy for a seat at the table, Randolph and the other leaders nearly destroyed the union. The “Lenin of Harlem” became a bureaucrat within a decade.

Victory

Between 1928 and 1937, when the first collective bargaining agreement was signed between the Pullman company and the BSCP, a few things happened. The Great Depression, and the rise of renewed labor militancy that would be exemplified in the explosive growth of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) terrified the Roosevelt administration. The AFL was also worried. The unions that would form the CIO, that unionized unskilled labor on an industrial basis that had previously been kept out of the AFL, made explicit calls on Black workers. As such, the AFL leadership started to budge, and for his part Randolph, the devoted anti-Communist, was not interested in the radical nascent CIO and remained loyal to Green. Thus, the Brotherhood was offered the international charter in 1935.

Likewise in 1935, changes in the law and the pressure of the government forced an election. By 8,316 votes to 1,422, the BSCP won union recognition. Another two years of struggle led to the first contract, which was signed on August 25, 1937, twelve years to the day of that first meeting in Harlem. The porters won a monthly wage of $175 for 240 hours and a grievance procedure. With a contract in hand, the Brotherhood grew to around 16,000 members in 102 locals by 1950.

From then on the BSCP continued fighting racism. In 1941, with the country preparing to enter World War II, Randolph and the BSCP demanded that the government outlaw discrimination in the workplace. When lobbying the administration did not work, Randolph proposed a massive demonstration to be organized by a coalition of working class and liberal forces, including the BSCP, and called it the March on Washington Movement. Before long, it looked like a hundred thousand people would attend. But — as during the aborted strike in 1928 — Randolph and the organizers of the march called it off after Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8802. The order nominally banned discrimination in hiring, but lacked any power to enforce companies’ compliance, while also leaving the military segregated. Still, Randolph and the BSCP became the old guard to the Civil Rights Movement that would reach its zenith in the 1960s. And though abandoned in 1941, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom did occur in 1963.

The long struggle of the Pullman porters for a union and against racism — a struggle they continued throughout their history and into 1978 when the union dissolved into the Brotherhood of Railway and Airline Clerks — illuminates the need for the labor movement to take up the cause of Black people and forge a deeper unity of workers against exploitation and oppression.