This article was originally published in Spanish in La Izquierda Diario

One striking quality about Lenin was his keen intellect in interpreting international political and economic situations and developing a plan for revolutionary action. In December 1900, at the age of 30, Lenin established Iskra, one of the most important projects of Lenin’s political life. Iskra laid the groundwork for a centralized organization of Russian Marxism which, until then, was fragmented into small isolated groups across Russia and in exile in Europe.

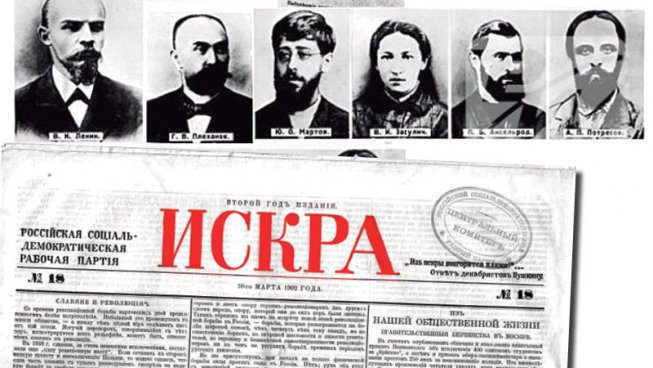

The first issue of Iskra (The Spark) was published in December 1900. Its motto was “a single spark can start a prairie fire.” Iskra helped organize and train a new generation of worker and intellectual cadres that would go on to form the vanguard of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP). The initial editorial board of Iskra was composed of six members: Vladimir Lenin, Georgi Plekhanov, Pavel Axelrod, Vera Zasulich, Aleksandr Potresov, and Julius Martov. In practice, Lenin was the director of the newspaper. He worked relentlessly writing letters to editors, making criticisms, and suggesting ideas for new articles.

In his book What is to Be Done? (1902), Lenin summarized the first two years of his work with Iskra. Towards the end of the 19th century, many workers had begun to embrace Marxist ideas as the Russian workers’ movement gained momentum. However, Lenin analyzed that, although the RSDLP had existed since 1898, mass arrests, deportations and spying by the Czarist autocracy rapidly disintegrated local cells that formed in the heat of conflict. These actions undermined efforts to create a centralized leadership of the revolutionary movement. The result was that Iskra had to be published in Europe and distributed from there to Russia.

Iskra’s fight against economism

Under the leadership of Lenin, Iskra was key in the political struggle against the economist opposition within Russian social democracy–the so-called “legal Marxists.” The economists defended strikes for economic demands, but were not as ready to embrace theoretical struggle. The economist opposition struggled within Russian social democracy in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to reduce the RSDLP program of abolishing the state to isolated trade union demands. Furthermore, the economist opposition was critical of the Iskra movement, saying it was organized outside of the traditional left-wing sectors and intervened in an autonomous fashion outside the RSDLP. To this, Lenin replied, “If we do not train strong, local political organizations, what value would a central, all-Russian newspaper have, even if it were excellently organized?”

Lenin defended his vision of Iskra, stating, “The proletariat, which is the most revolutionary class in today’s Russia only if it succeeds in organizing itself into such a party, will be able to perform the historic task for which it is destined: to unite under its banner all the democratic elements in the country, and to lead this struggle, reinforced by so many sacrificed generations, to a triumph over the hated regime.” The economists separated the trade union struggle–undertaken by the working class–from the political struggle, led by theorists and intellectuals. Lenin, on the other hand, saw Iskra as a revolutionary political newspaper that would be published for workers, and aimed at uniting the whole movement and raising the theoretical level of the vanguard (1).

Revolutionary press plays a different role from bourgeois press. It is the most suitable means to influence events and organize the militant and revolutionary base of a workers’ party.

Lenin’s political intransigence would not keep him from discussing with the great leaders of the international social democratic movement. Lenin invited Rosa Luxemburg and Kautsky, among others, to write in Iskra (despite their political differences) in order to fuel debate and critical spirit. This was central in his idea of journalism, debunking historical falsifications that portray Lenin as an “authoritarian leader.”

Press as “scaffolding”

As Iskra continued to be published as a revolutionary press underpinning the Russian social democratic movement, the leaders of Russian social democracy edited Iskra from overseas while an extensive network of local reporters formed the backbone of the newspaper. Iskra had representatives in Berlin, Paris, Switzerland and Belgium who collected funds to finance the publication-– veritable internationalism as praxis.

This structure gave vitality to Iskra. For Lenin, these networks “could be compared to the scaffolding around a building under construction, marking its contours, facilitating the relationship between different sectors, helping them share the work and measure the overall results of the organized effort.” In this “scaffolding” structure, Iskra could unite the scattered groups and their conflicts by translating international mobilization against hunger and exploitation into organized class struggle. This organized struggle was best expressed in the motto, “A newspaper of agitation for all Russia,” that would unify the fight against the Czar.

Newspaper and party

The Iskra experience provided the basis of the party newspaper that Lenin had in mind, guided by the idea crystallized in this excerpt from What is to Be Done?:

“The mission of the newspaper is not limited, however, to disseminating ideas, providing political training and attracting political allies. The newspaper is not only a collective propagandist and a collective agitator, but also a collective organizer.”

In line with the strategy of being an organizing tool, Lenin adapted his idea of a revolutionary newspaper to new circumstances and created Pravda (Truth) in 1912 when the workers’ struggles began to escalate. Pravda was the newspaper of the revolutionary party that would triumph in gaining state power in Russia in October 1917.

Today, revolutionary Marxists should place the goal of politically organizing the working class as top priority. As Partido de los Trabajadores Socialistas (PTS), we seek to contribute to this task with the online and print versions of La Izquierda Diario. In the next article, we will examine the foundation and the consequences of the creation of Pravda.

Notes

(1) The political struggle within Iskra allowed the expression of the trends which concretized in the split at the Second Congress of RSDLP held in July – August 1903. The Bolsheviks argued that every member had to participate in some instance of the organization (interestingly enough, during the Pravda period, Lenin would have another idea about militancy). The Mensheviks had a laxer viewpoint and ended up growing closer to the positions of the liberal bourgeoisie. The new Editorial Board had three members: Plekhanov, Lenin and Martov. When Plekhanov leaned towards the Mensheviks (Martov was already a leader of this latter faction), Lenin -in minority- decided to leave the Editorial Board in November 1903.

Translated by Baris Yildrim

Copy-editor Connie White