The following article originally appeared on La Izquierda Diario in Spanish.

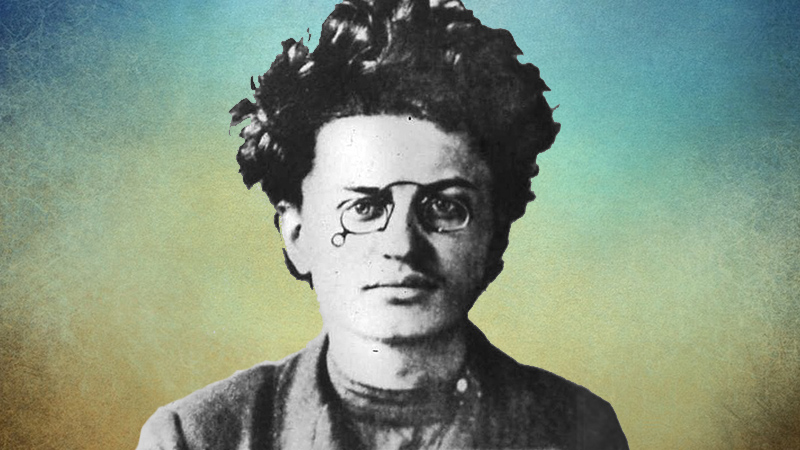

“The facts of my personal life have proved to be so closely interwoven with the texture of historical events that it has been difficult to separate them.” – Leon Trotsky, My Life (1930)

The day that Leon Trotsky turned 38 years old, he directed the taking of the Winter Palace with Vladimir Lenin, an accident, of course, but an accident that shows how Trotsky’s personal life was interwoven with historical events. November 7 is a day to remember in history, even 100 years later. Not only it is Trotsky’s birthday but also the day that the oppressed and exploited came to power in Russia, led by the Bolshevik Party.

Trotsky even pointed this out himself. In My Life, he says, “The date [of my birthday] coincides with that of the October revolution. Mystics and Pythagoreans may draw from this whatever conclusions they like. I myself noticed this odd coincidence only three years after the October uprising.”

Until he was 9 years old, Trotsky lived in the country with his land-owning family. His life changed substantially in 1888 when he was sent to study in Odessa, far from his family and home. He describes this period thus: “The awakened hunger to see, to know, to absorb, found relief in this insatiable swallowing of printed matter, in the hands and lips of a child ever reaching out for the cup of verbal fancy. Everything in my later life that was interesting or thrilling, gay or sad, was already present in my reading experiences as a hint, a promise, a slight and timid sketch in pencil or water-color.”

His seventh year of school was spent in Nikolaiev, where his leftist militancy began to develop through political exchanges with leftist workers and students. This experience allowed him to make close contact with the workers while taking his first steps on the road to revolution. After supporting workplace organizing, Trotsky was arrested by the Tsarist regime. Prison, deportation, and exile were Trotsky’s university.

During his tenure in prison, things started to change. The students were protesting against the autocracy. Social democracy was gaining strength and increasingly merging with the workers’ movement. The prisons were full of workers and leftists incarcerated for organizing. While in the Moscow prison, Trotsky devoted his time to advancing in theoretical study. It was there that Trotsky first heard of Lenin and read his book on the development of Russian capitalism. In the fall of 1900, Trotsky was deported to Siberia. It was in those freezing lands that Marxism would become the basis of his conception of the world and his method of thought.

While in prison, Trotsky received reports that a Marxist newspaper, Iskra, had been founded abroad. Iskra was more than just a paper; it was a Marxist voice that aimed to build a centralized organization of professional revolutionaries. While in prison, he also read Lenin’s pamphlet “What it is To Be Done,” dedicated to an examination of how to build a revolutionary organization. Convinced by these ideas, Trotsky began to plan his escape from Siberia to join the Iskra staff. He describes an experience riding the train: “In my hands, I had a copy of the Iliad in the Russian hexameter of Gnyeditch; in my pocket, a passport made out in the name of Trotsky, which I wrote in it at random, without even imagining that it would become my name for the rest of my life.”

After a long journey by sleigh, train, and ship, he arrived in London in 1902 and joined the editorial staff of Iskra with Lenin and other important leaders of the Russian Social Democracy such as Plekhanov, Zasulich, and Martov.

In remembering those years, Trotsky reminisces, “In prison, I had to start my revolutionary education almost from the abc’s. Two and a half years in prison and two years of exile in Siberia gave me the theoretical foundations for a revolutionary view of life. My first stay abroad was my school for political education. Under the guidance of distinguished Marxist revolutionaries, I was learning to understand events in a broad historical perspective and in their international context.”

Bolsheviks and Mensheviks

In 1903, at the II Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Party, two factions emerged in the election of the Central Committee and the Drafting Committee of Iskra; the vote was divided between the Bolsheviks (majority led by Lenin) and the Mensheviks (minority led by Martov). Although these differences seemingly revolved around organizational issues, they actually expressed deeper strategic differences. Trotsky says that “at the time of the London Congress in 1903, revolution was still largely a theoretical abstraction to me. Independently I still could not see Lenin’s centralism as the logical conclusion of a clear revolutionary concept. And the desire to see a problem independently, and to draw all the necessary conclusions from it, has always been my most imperious intellectual necessity”.

The Second Congress separated Trotsky from Lenin for several years; Trotsky believed that the Bolsheviks and Mensheviks could find common ground and unite under a single party. At the same time, Trotsky agreed with Lenin about the need for absolute independence of the working class from the capitalists, a position the Mensheviks disagreed with.

It was not until 1917 that Trotsky joined the Bolshevik Party in the heat of the mass movement towards revolution. After reading the April Thesis, Trotsky and his group called Interdistrictites joined the Bolsheviks. Once Trotsky joined the Bolsheviks, Lenin said that “from that time on there has been no better Bolshevik.”

However, in his later reflections he affirms that “when I consider the past as a whole, I do not regret what happened. I returned to Lenin later than many others, but I did it on my own path, having traversed and meditated on the experience of the revolution, the counterrevolution, and the imperialist war. Thanks to these circumstances, I returned to him more firmly and seriously than those of his ‘disciples’ who, when he was alive, imitated him, sometimes incorrectly, in his words and gestures; and then, after his death, they revealed themselves to be impotent epigones and unconscious instruments in the hands of enemy forces.”

1905: the first Russian Revolution

The year began with a strike by the workers of the Putilov factory, which quickly spread to other factories in St. Petersburg. On Sunday, January 9, about 200,000 workers mobilized to call on Czar Nicholas II to give them greater public liberties. This was by no means a revolutionary march; it was a non-violent march led by Father Georgy Gapon. The government unleashed fierce repression on the crowd, and hundreds were killed and wounded. The bloody response by the government to these basic and minimal demands radicalized the Russian people. “Bloody Sunday” was the first act of the open revolutionary process. The three most intense months of the 1905 Revolution were October, November, and December.

The working class demanded the end of the autocracy, the separation of the Church and State, amnesty for the imprisoned fighters, and the creation of a Constituent Assembly. It was in the heat of the months-long general strike against the autocracy that the first Soviet (Council) of Workers’ Deputies emerged. The Soviets met for the first time on October 13 in the city of Petersburg and became the center of strike activity. Representation in the Soviets was based in the workplaces and was the primary connection among the proletarian masses. One delegate was elected for every five hundred workers, and their mandate was revocable. Upon returning from exile, Trotsky was voted to the leadership of the Petrograd Soviet at just 26 years old.

The attempt at revolution in 1905 demonstrated that the proletariat did not yet have hegemony over other sectors of society. The military was still on the side of the Tsar. Repression at the hands of the Army and the Cossacks accelerated, and members of the Soviet, including Trotsky, were arrested. The Moscow Soviet called a general strike with the intention of turning it into an insurrection. However, the resistance was isolated in the cities, resulting in its inevitable defeat in December of 1905.

Another factor that led to the defeat was the lack of a revolutionary party based on the working class. A revolutionary party must have organization, experience, and the ability to take power. The Bolshevik Party had all of these things in 1917.

At the young age of 26, Trotsky had been through Tsarist prisons, deported, and exiled. He had been an editor of Iskra, and he led the Petersburg Soviet. After the failed 1905 Revolution, he formulated the basis for his theory of the “Permanent Revolution,” arguing that the working class would bring about a socialist revolution in a backwards country like Russia, leading the peasants against both the capitalists and the landed aristocracy.

The 1905 Revolution was essential in the formation of Trotsky as a revolutionary, in both theory and practice. But this was just the beginning of a life committed to the fight for socialism marked by crises, wars, and revolutions.