In the past few weeks a debate has been taking place inside the recently formed Revolutionary Socialist Organizing Project (RSOP). The debate centers around revolutionary organization, what the orientation of revolutionaries should be, how we engage with the broader Left, and what methods are needed to politically develop the revolutionary vanguard and the broader working-class and oppressed masses.

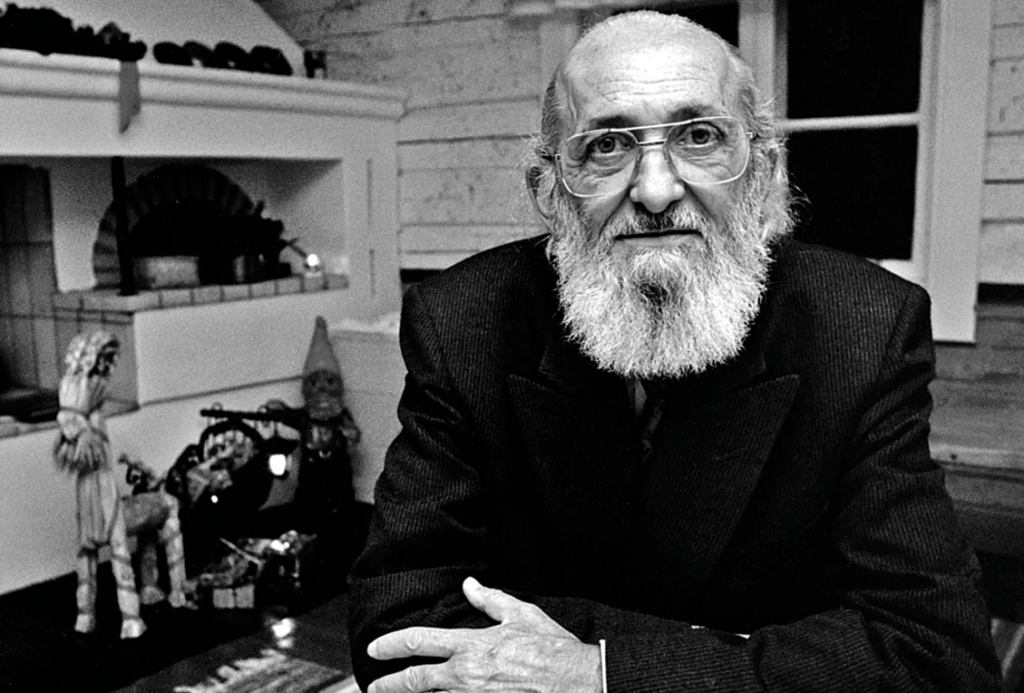

A faction within the RSOP raised Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed as a model that revolutionaries can use to answer some of the issues raised in the debate. What follows is a critique of Freire’s work, one that points out the flaws of using his work as a model for revolutionary organizing.

Pedagogy of the Oppressed starts off with a critique of what Freire calls the “banking method” of education, in which the teacher is the sole arbiter of truth. The students know nothing and must learn by receiving “deposits” of knowledge. According to Freire, those who approach education with the banking method view it as an exercise in rote memorization and blind acceptance of a list of facts, procured by the teacher. Freire criticizes this system as dehumanizing.

Freire contrasts this with “problem-posing” education, wherein the teacher and the student both learn as co-investigators of the subject. Rather than “depositing” knowledge, the teacher poses problems to the students and works with them to find solutions. Though the teacher may know a solution, they do not directly state it, instead probing and guiding the students until they come up with a solution themselves. For political education specifically, Freire proposes forming discussion circles centered around the issues in the community, such as racism, low wages, patriarchy, etc. The coordinators of these discussion groups, according to Freire, should restrict themselves to only posing these problems, not discussing solutions. Doing so will allow the participants to produce solutions themselves. After conducting these discussion groups, the coordinators produce reports on them and discuss the results.

Throughout the book, Freire analyzes the relationship between oppressors and oppressed. He argues the banking model serves the interests of the oppressors, and he promotes problem-posing education as a liberatory alternative. He argues that the banking method cannot be used for liberatory purposes.

In the final chapter, Freire applies the critique of the banking model and its use by the oppressing class to the arena of politics. According to Freire, revolutionary leaders must break down the hierarchy created by the banking model and instead engage in dialogue with the oppressed if they are to succeed. He contrasts the characteristics of the political strategy of the oppressors with that of the revolutionary leaders. For Freire, oppressors maintain their political power through conquest (convincing the oppressed of myths that maintain the status quo), divide and rule, manipulation, and cultural invasion (convincing the oppressed to take on the norms and culture of their oppressors). In contrast, revolutionary leaders should promote cooperation, unity, organization, and cultural synthesis (overcoming the contradiction between leaders and led, eliminating the idea of a “superior culture,” undoing cultural invasion).

Freire’s book contains many interesting critiques of oppression and its effects. He clearly has a deep interest in overcoming oppression. His emphasis on dialogue between revolutionary leaders and the oppressed is welcome. There are still too many on the Left today who see revolutionary socialism as a political project to be imposed from above rather than to be developed from below.

While the book serves as an interesting critique of certain aspects of capitalist society, its use in political organizing is problematic. One major problem is that Freire’s approach to education is not useful for training activists in Marxism or in organizing workers for struggle. The approach has two underlying, unstated assumptions that need to be challenged: (1) workers can be convinced to struggle against oppression through education alone, and (2) workers automatically come to revolutionary conclusions.

It’s hard to see how simply posing the problems of racism, low wages, climate apocalypse, etc., to average people would lead them to formulate a single viable political solution. Workers largely already know which problems are most pressing. It does not take a revolutionary to inform workers that their wages are too low or that climate apocalypse is on our doorstep. What we need is leadership and solutions. When political issues do arise, the working class tends to come to a variety of political solutions — some worth considering, others much less so. The duty of revolutionaries is to identify which political solution has the most revolutionary potential and to argue for it.

For example, during the Black Lives Matter rebellion of 2020, the issue of police brutality came to the fore. The liberals proposed retraining the police to be less violent. The conservatives defended the status quo. The Left argued for defunding the police. In this case, the correct course of action was to point out the fundamentally reactionary, racist nature of the police and to win other activists to the idea of defunding the police. But following Freire’s logic, revolutionaries should have just stood aside and engaged in neutral, probing dialogue instead. In fact, Freire implies that political argument is unnecessary or even harmful (from chapter 3 of Pedagogy of the Oppressed):

[Revolutionary leaders] forget that their fundamental objective is to fight alongside the people for the recovery of the people’s stolen humanity, not to “win the people over” to their side. Such a phrase does not belong in the vocabulary of revolutionary leaders, but in that of the oppressor. The revolutionary’s role is to liberate, and be liberated, with the people — not to win them over.

If revolutionaries do not need to win workers to the idea of revolution, then being part of a broad movement is enough. Why bother trying to found a revolutionary party at all? If the objective of revolutionary leaders is simply to “fight alongside the people,” then the people are already on their way to the revolution. We simply need to stand aside and let it happen!

The working class as a whole does not automatically come to revolutionary conclusions. Mixed consciousness is the norm. In nonrevolutionary times, revolutionaries will be a political minority, by definition. This means that taking a revolutionary stance will usually be controversial and alienate a large section of the working class. Since nonrevolutionary times are the norm for capitalist society, revolutionaries must be comfortable with being a political minority for a long time.

To really win a revolution, or even reform struggles, firm, tested ideas are required. The role of Marxists is to furnish these firm, tested ideas to the working class in the course of struggle. As Lenin said, revolutionary socialists must “patiently explain” and win over workers to their viewpoint. There is no substitute for democratic political debate. There is no substitute for revolutionary leadership. This is not the same thing as imposing a political regime from above; in fact, to win a real revolution, workers must be completely convinced of the superiority and necessity of socialism.

Apart from casting aside the essential tools of debate and political argument, Freire’s approach is idealistic. It rests on the assumption that the primary obstacle to working-class liberation is the perception of oppression or average people’s ideas about the world. This quote from chapter 3 sums this up pretty well:

Thus it is not the limit — situations in and of themselves which create a climate of hopelessness, but rather how they are perceived by women and men at a given historical moment: whether they appear as fetters or as insurmountable barriers. As critical perception is embodied in action, a climate of hope and confidence develops which leads men to attempt to overcome the limit-situations.

Here, “limit-situation” refers to a concrete political reality that constrains the humanity of certain people — i.e., oppression. True, Freire does recognize the need for the understanding of oppression to translate into real action to fight it. But it is only under certain objective circumstances that average people become open to new political ideas and become willing to fight. These circumstances cannot be created by revolutionaries through education alone. Rather, these circumstances are created by capitalism itself. For this reason, revolutionaries must intervene when circumstances arise and hold firm to our politics when in nonrevolutionary times.

For example, the Black Lives Matter movement of 2020 after George Floyd’s murder happened against the backdrop of a string of increasingly brutal and unjustifiable police murders, as well as the emergence of the Covid-19 pandemic, which had suddenly left millions of people unemployed. The uptick in unionization and worker struggle in 2021 happened amid a historically tight labor market, giving workers newfound confidence. The unfortunate reality is that revolutionaries cannot simply conjure these circumstances whenever we like.

It is during times such as these that intervention becomes essential. Intervention can take many different forms, depending on the movement, the issues, etc. Sometimes it could be passing out a flyer with a revolutionary perspective at a protest, giving a speech at a rally, convening a reading group, or any number of other actions. But the space for intervention among broader layers of workers and the oppressed exists only under certain objective circumstances. For example, at a recent rally in support of Starbucks unionization in Seattle, a few speakers brought up the dangers of business unionism. In the past, such speeches might not have been well received. But amid several new unionization efforts and a series of high-profile sellout contracts from various union leaderships, they were instead met with applause.

Freire’s idealism leads either to opportunism or ultraleftism. When the organizers of these discussion circles eventually realize that some people simply cannot be convinced, no matter how much they poke and prod, they will be forced into believing either that their politics are wrong and need to be adjusted (opportunism) or that the participants are not oppressed enough to be revolutionaries (ultraleftism).

Another major problem with Freire’s analysis is his conception of the oppressed-oppressor dichotomy. Throughout the book, Freire contrasts the conflicting interests and views of the oppressed and the oppressors. He gives no indication that anyone can belong to both categories, or be something in between. In fact, Freire seems to think that “professionals” and other middle-class layers belong to the category of oppressor alongside the capitalists, if this quote from chapter 4 is any indication (for context, “steering,” “conquering,” and “cultural invasion” are, for Freire, tactics of the oppressor):

The fear of freedom is greater still in professionals who have not yet discovered for themselves the invasive nature of their action, and who are told that their action is dehumanizing. Not infrequently, especially at the point of decoding concrete situations, training course participants ask the coordinator in an irritated manner: “Where do you think you’re steering us, anyway?” The coordinator isn’t trying to “steer” them anywhere; it is just that in facing a concrete situation as a problem, the participants begin to realize that if their analysis of the situation goes any deeper they will either have to divest themselves of their myths, or reaffirm them. Divesting themselves of and renouncing their myths represents, at that moment, an act of self-violence. On the other hand, to reaffirm those myths is to reveal themselves. The only way out (which functions as a defense mechanism) is to project onto the coordinator their own usual practices: steering, conquering and invading.

This overly simplified dichotomy, combined with Freire’s idealism, leads him to ascribe every reactionary tendency of the oppressed merely to internalizing the image of their oppressor, while the actions of the oppressor are completely intentional and malicious. There is no discussion of the economic interests of either “class” in the book, no discussion whatsoever of how the objective circumstances shape the people in question. The oppressed are merely confused saints waiting to take their rightful place as humanity’s savior, while the oppressors are irredeemable demons.

In reality, it is the objective circumstances that give space for oppressive ideas. This is because people tend to justify the things they are compelled to do. For example, since women’s wages are often less than men’s, it often makes economic sense for women to drop out of paid work entirely and look after the children. This objective circumstance is, in part, what creates space for the idea that women’s “natural place” is at home. Able-bodied workers generally feel alienated and exhausted after a full day of work and long for nothing more than rest. This is what gives rise to resentment among some able-bodied workers toward those who are disabled, since they appear “free” from wage labor. Oppressive ideas are, of course, promoted by the ruling class to sow division among the working class and get them to acquiesce to capitalism. The role of bourgeois propaganda should not be understated. But without the objective circumstances created by capitalism, oppressive ideas, much like their revolutionary counterparts, would find no audience.

As Marxists, we must reject a political approach that idealizes the oppressed or any other group of people. Marxists must instead base their analysis on the material reality of people in our society. We view the working class as the only basis for socialism in our society because socialist revolution is in the class interest of the working class, and because all wealth ultimately derives from the labor of the working class, workers have the economic basis to reorganize society. Revolutionaries do not push for socialism out of moral concern or charity for the oppressed. We do so because we are workers ourselves, because we see that capitalism is an existential threat to us and to all of humanity, and that socialism is the only viable path forward.

As Marxists, we have a duty to argue against ineffective and harmful political approaches when we see them. Every social movement that failed because it adopted a reformist or utopian approach represents a lost opportunity for Marxist intervention. The need for revolutionary change has never been more urgent. Amid the backdrop of eroding civil liberties and reproductive rights, rapidly worsening climate change, rampant inflation and more, the choice between socialism and extinction has never been more stark. Our role is to make that choice clear for the working class as well.