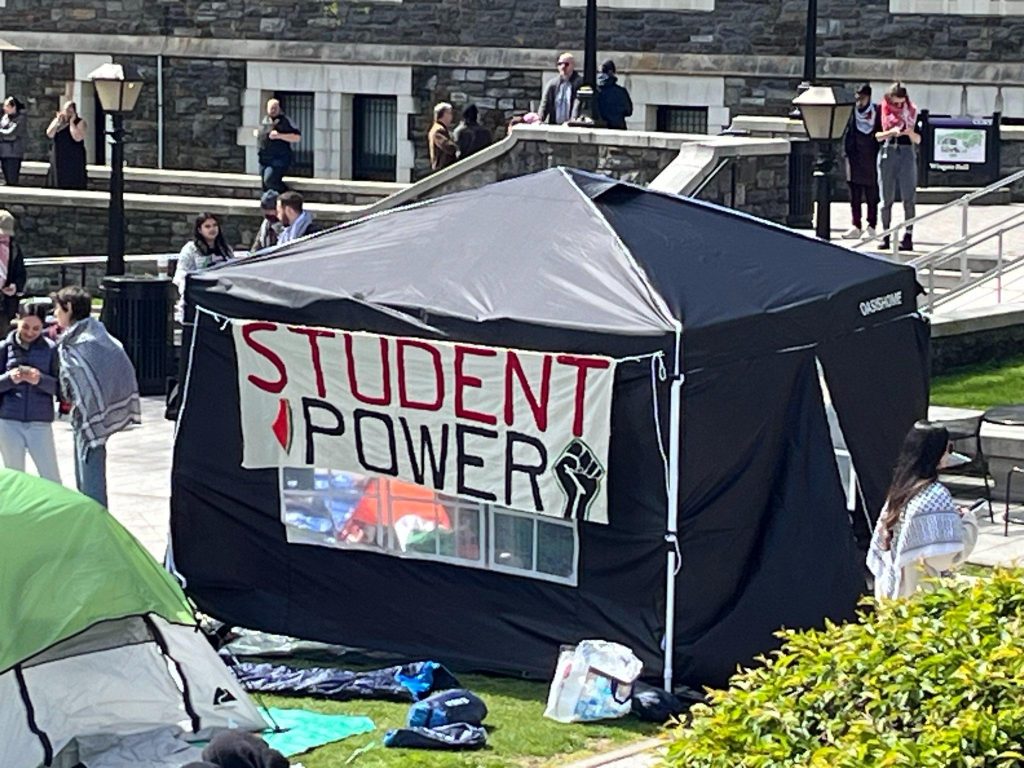

As of 9:30 a.m. Thursday, the spirit of the University of Harlem has been resurrected in Hamilton Heights as “Intifada University” on the campus typically known as the City College of New York (CCNY). Students from across the City University of New York’s 25 campuses assembled on the quad and set up a Gaza Solidarity Encampment, joining other campus encampments springing up across the United States and around the world. The encampment is taking inspiration from the CCNY occupation of 1969, which put forward five demands to combat racism at the university. One of the main banners from the 1969 occupation read “Support the Five Demands, Viva Harlem U,” and now the main banner of the Gaza Solidarity Encampment reads, “Support the Five Demands, Viva Palestina.” Like the other encampments, this one is demanding that the university divest from Israel and companies that manufacture the weapons being used in Palestine, along with four other demands, including a demand for “A People’s University,” which includes making CUNY tuition-free again, providing students with other forms of material support like MetroCards and health care, and meeting the contract demands of the faculty, staff, and graduate assistant union, PSC-CUNY (AFT Local 2334).

“University of Harlem” was the name given to the campus during the occupation of April 1969. Those students’ five demands pertained to racial justice on campus, and they took inspiration from the 1968 occupation of Columbia, which some of the CCNY students had attended in solidarity. The current movement for campus divestment is the biggest set of campus uprisings since the movement against the Vietnam War in the 1960s and 1970s. Much has been said over the last two weeks about the 1968 Columbia occupation, but in 1969, City College students organized as the Black and Puerto Rican Student Community took over South Campus, leading classes to be canceled for two weeks in late April and early May, exactly the timeframe of this current occupation. Allied white students occupied another building on North Campus in support.

In the last few years, most of the student activism at City College has come from its Muslim student population; in 2022, students rallied for an interfaith prayer space, and since October 7, most protests on campus have been organized by the CCNY chapter of Students for Justice in Palestine. But even though other campuses like Hunter College have a more of a reputation for political organizing now, City College has historically been a center for student political activity, especially in the 1930s and 1960s, and also in the 1990s.

Student Anti-fascist Organizing in the 1930s

I’ve previously written about faculty organizing at City College in the 1930s and 1940s and student organizing in support of faculty being targeted by anti-Communist hearings. But students did an enormous amount of organizing of their own during this period too.

In the 1930s, most of the City College student body consisted of Jewish, working-class New Yorkers from immigrant families struggling to pay the bills during the Great Depression. They were excluded from institutions like Columbia, not only because they were poor but also because admissions quotas excluded Jewish students, especially those of Eastern European descent. While the ethnic composition of City College has changed in the last 90 years (now most CCNY students are Latinx or Asian), the majority still come from low-income families, and many are immigrants or children of immigrants. The alcoves of the old cafeteria in the basement of Shepherd Hall were the gathering places of leftists of varying tendencies, divided into Stalinist and anti-Stalinist camps. Students protested and went on strike from their classes regularly during the 1930s and early 1940s, protesting the presence of the ROTC on campus, the repression of fellow students and faculty, the draft, fascism, and other issues.

One story from this period will seem familiar to those following the Columbia occupation. On May 29, 1933, students marched to Lewisohn Stadium, which stood where the North Academic Center is now, to protest the ROTC and U.S. imperialism more generally. The college president at the time, Frederick B. Robinson, called the police on the protest, resulting in several student suspensions, the dismissal of a faculty member, the dismissal of several student clubs, and the banning of a student publication. Allegedly, Robinson also hit several students with his umbrella — an incident he never lived down, resulting in a recurring umbrella motif in student mockery for the rest of his tenure. The protest was the subject of media outrage and misinformation, and students put out a flyer to correct the misinformation shortly after, along with advertising a follow-up demonstration in protest of the suspensions. Alumni signed a letter in solidarity. The next year, 21 students were suspended in October at an anti-fascist rally, and their classmates walked out in their defense.

On April 22, 1936 — exactly 63 years before students occupied South Campus in 1969 — over 3,500 students and faculty walked out for a “strike against war” as part of a nationwide day of action coordinated by the American Students Union (500,000 students participated around the country). The resolutions and demands proposed at the rally included the abolition of the campus ROTC, the idea that “war anywhere is war everywhere” and a condemnation of imperialism; the defense of academic freedom and reinstatement of suspended students; official recognition of the CCNY chapter of the American Student Union; the redirection of military funds to pay for books, the end of student fees, and higher wages for faculty and staff; and the refusal to support any war conducted by the United States.

While the demands of today’s movement are more specific to Palestinian liberation instead of a broad anti-war stance, there are clearly many resonances between the demands of the campus then and the demands of the campus now. Mid-April demonstrations for peace and for academic freedom became an annual event that one journalist in 1991 described as part of the “rites of spring” at CUNY. The CUNY encampment continues that tradition but expands the demands beyond peace in general and opposition to U.S. militarism, calling specifically for a free Palestine.

Student Anti-racist Organizing in 1969

On April 22, 1969, students took over the campus, renaming it the “University of Harlem” or “Harlem University,” depending on the banner. Their now-famous “Five Demands” included (1) a school within the college dedicated to Black and Puerto Rican Studies; (2) a dedicated freshman orientation for Black and Puerto Rican students; (3) joint power over decision-making in the SEEK program, which serves low-income students in need of financial and academic support; (4) admission to City College for any high school graduate regardless of their grades, along with the necessary academic support to succeed; and (5) a requirement that all education majors take classes in Black studies, Puerto Rican studies, and Spanish, in order to better serve the students of New York City. Minor progress had been made in negotiations over the demands in the preceding months, but the students remained unsatisfied, resulting in the campus takeover and cancellation of classes for two weeks.

Queens College students also walked out on April 22, 1969, and later occupied a building on their own campus. Brooklyn College students released their own 18 Demands that same month. As is always the case, faculty perspectives on the occupations and other campus protests differed. Action, the newspaper of the United Federation of College Teachers (UFCT), the more radical one of the two competing faculty unions at the time, dedicated space in its May 1969 issue for faculty to present their positions and arguments.

While occupying South Campus, the students opened their occupation to members of the Harlem community, offering food, medical services, access to teach-ins on political theory, and tutoring. This community-oriented approach is evident in the current CCNY occupation as well. Unlike those at many other schools, CUNY activists are explicitly inviting members of the community to join them at their encampment. Student activists are acutely aware of the differences between CUNY and Columbia, but they are also acutely aware of CUNY’s position as a working-class university, inseparable from the working class of New York City. Eighty-two percent of CUNY students attended a NYC public high school, 80 percent of its graduates are still working in New York State 10 years after graduation, and CUNY graduates make up 17 percent of the statewide workforce with a college degree — and many more New Yorkers have some college credit from CUNY without completing a degree.

Compared to 1969, it’s more difficult to force a college to cancel classes through student activism because the pandemic has left us with Zoom class as a familiar and feasible option. For instance, rather than canceling class, Columbia has moved all classes online for the time being. CUNY students are on spring break right now; it remains to be seen what the university will do once classes resume on May 1 — which is also May Day, or International Workers Day, when much of New York City’s labor movement will be mobilizing for both annual May Day activities and a rally for Palestine. The CUNY faculty today are also fiercely arguing about the campus protests and how to respond to them, just like their colleagues who published in the May 1969 issue of their union newspaper, but unlike in 1969, these arguments are primarily taking place over email. Hopefully these private arguments will result in increased faculty solidarity with and attendance at the encampment.

Student Occupations against Budget Cuts in 1991

The last campus occupations at CUNY took place in April 1991, according to records in the CUNY Digital History Archives. These were in response to a proposed $500 tuition increase and devastating budget cuts under Governor Mario Cuomo. Students at nine CUNY schools occupied buildings and staged sit-ins as part of a three-week set of protests. This series of occupations began at the City College’s North Academic Center (NAC), an imposing brutalist building built some time after the 1969 protests.

In their promotional flyer, the City College strikers explicitly tied their fight against the cuts to the fights against racial oppression, against working-class exploitation, and against the first Gulf War. These students also practiced basic principles of democratic self-organization, holding daily assemblies on campus in the evening to “discuss and resolve the situation in the CUNY system and make collective decisions in activity, our strategy and tactics and on which way forward will fight and win.”

Student protesters across the country are rapidly learning lessons in organizing from each other, from the protests of the past, and from activist elders and mentors. To sustain the movement, it will be important to practice collective and democratic decision-making and to rally the support of the broader campus and municipal communities, as protesters at Columbia have done, drawing over 1,000 supporters at a Tuesday night midnight deadline set by the university. Fears ran high about the National Guard or at least another attack by the NYPD, but the throngs of people, ranging from supportive to merely curious, showed the administration that any further repression would only fuel their outrage. Faculty and staff at Columbia are organizing in solidarity with the encampment, as have faculty at NYU and elsewhere, and this must be one of the next steps to massify and sustain the movement. The faculty at the University of Texas at Austin went on strike on Thursday in response to state troopers repressing their students yesterday. Every student encampment makes the whole movement stronger, and every worker action in support helps protect it.

Student activists at the CUNY encampment at City College this week are standing on the shoulders of giants, the campus organizers of decades past. Today, they are creating their own chapter in our university’s proud history of working-class struggle against imperialist violence, against student and faculty repression, and against oppression, this time focusing their gaze on the ongoing genocide in Gaza.

As the faculty, staff, and graduate assistant union’s T-shirts say, “Everybody loves somebody at CUNY” — and everybody in our CUNY community should come out to City College to support the encampment.