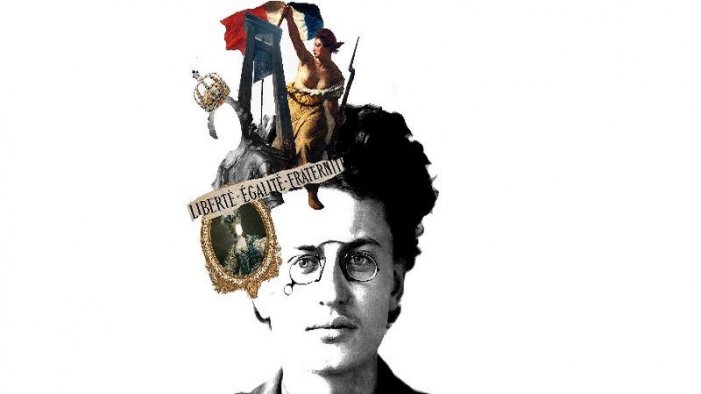

Leon Trotsky was a student of the 17th- and 18th-century bourgeois revolutions. But was it mere scholarship, or was he sharpening his critiques so they could be used as a weapon? Are historical analogies valid for any situation, for any time and place? What is the point of comparing two revolutions? These are the questions I will try to answer.

Prison Writings

After the defeat of the 1905 revolution in Russia, when Trotsky was in prison, he wrote with the next revolution in mind. To ensure its victory, he needed to understand the bourgeois revolutions. Other comrades imprisoned with him said later that his cell became a library where he read and wrote, joking ironically that they no longer had to hide from the police.1Translator’s note: The reference is to Trotsky’s autobiography, in which he mentions D. Sverchkov’s description of their imprisonment together. Trotsky quotes Sverchkov’s memoir At the Dawn of the Revolution. See Trotsky, My Life, chap. 15, “Trial, Exile, Escape.”

It was there he wrote Results and Prospects (1906). In one of its chapters, he reflects on three revolutions: 1789 and 1848 in France and 1905 in Russia. He gives an account of the revolutionary potential of the bourgeoisie in 1789, not only to rise up against the Old Regime of France, but against reactionary monarchism across Europe. So, the French Revolution became a national one in the sense that all the people participated: the petty bourgeoisie, the peasants, and the workers. That aggregate of classes elected members of the bourgeoisie as deputies, who bestowed upon the masses an ideology and a political orientation — Jacobinism.

Having explained that, Trotsky puts forth a combined criticism and vindication of Jacobinism, writing:

The bourgeoisie has shamefully betrayed all the traditions of its historical youth, and its present hirelings dishonor the graves of its ancestors and scoff at the ashes of their ideals. The proletariat has taken the honor of the revolutionary past of the bourgeoisie under its protection. The proletariat, however radically it may have, in practice, broken with the revolutionary traditions of the bourgeoisie, nevertheless preserves them, as a sacred heritage of great passions, heroism and initiative, and its heart beats in sympathy with the speeches and acts of the Jacobin Convention.2Trotsky, Results and Prospects, chap. 3, “1789 – 1848 – 1905.”

He argues that in the early years of the 20th century, the bourgeoisie reconfirmed its political cowardice. For this reason, he reflects on the 1848 revolutions, when the bourgeoisie camouflaged itself with revolutionary phraseology but was no longer even a tenth of what Jacobinism had been. The French Leftist philosopher and political writer Alain Brossat has called this type of “intermediate” revolution, like those of 1848, the “no longer” of the bourgeois revolutions and the “not yet” of the proletarian revolutions.

Karl Marx wrote that “all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice … the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.”3Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, chap. 1 (1852). He was describing the change of the era, when the bourgeoisie had already mutated and begun to show its reactionary characteristics. If that was the case for 1848, then in the imperialist epoch Trotsky was analyzing there was no path the bourgeoisie would take other than to guarantee the continued exploitation of the working class at any cost.

Dual Power

In analyzing the February 1917 revolution in his book The History of the Russian Revolution, Trotsky notes the revival of the soviets (councils) of workers’, soldiers’, and peasants’ deputies. The masses took the path of self-organization. Trotsky returns to the experiences of dual power in the bourgeois revolutions of both 17th-century England and 18th-century France. He points out that the existence of a situation of dual power occurs in the framework of the struggle between a class that is “dying” and another one that is “being born.” He argues that the situation of dual power does not last forever, but is resolved through civil war or, in other words, through the struggle between revolution and counterrevolution.

With respect to the French Revolution, he argues that the bourgeoisie made its Convention into a dual-power body that fought against the absolutist aristocracy, and that the duality was formally resolved with the declaration of the Republic. But he warns that within that duality, and within that revolutionary camp, there is another duality4Translator’s note: Trotsky refers to it as “a new double sovereignty” that “with increasing boldness contests the power with the official representatives of the national bourgeoisie.” that is expressed by the pressure the people exert on the bourgeoisie to go beyond its intentions. In this regard, he writes of the plebeians:

It seemed as though the very foundation of society, tramped underfoot by the cultured bourgeoisie, was stirring and coming to life. Human heads lifted themselves above the solid mass, horny hands stretched aloft, hoarse but courageous voices shouted! The districts of Paris, bastards of the revolution, began to live a life of their own. They were recognized — it was impossible not to recognize them! — and transformed into sections. But they kept continually breaking the boundaries of legality and receiving a current of fresh blood from below, opening their ranks in spite of the law to those with no rights, the destitute sans-culottes.5Translator’s note: The sans-culottes (French for “without breeches”) were the lower-class commoners of late 18th-century France who comprised the militant popular partisans of the revolution. The term, which was used to distinguish these pants-wearing urban laborers from the nobility and bourgeoisie who wore fashionable silk breeches, was coined by a French general and used derogatorily, but came to be embraced by the revolutionary masses. At the same time the rural municipalities were becoming a screen for a peasant uprising against that bourgeois legality which was defending the feudal property system. Thus from under the second nation arises a third.6Trotsky, The History of the Russian Revolution, chap. 11, “Dual Power.”

Of course, that dual power, born from the working-class districts of Paris and from the poor peasants across all of France, would be trampled underfoot as the radical political objectives of the revolution expanded. The movement began to decline because the bourgeoisie realized that its new privileges, especially the sacred “privilege” of “private property,” had to be sacrosanct.

In the case of the Russian Revolution, dual power was resolved by the soviets taking power, with Trotsky as the great organizer of the insurrection.

The French historian and Trotskyist Pierre Broué once wrote:

Reading and rereading the passages in Trotsky’s work that discuss the French Revolution fuels the disappointment over the absence of a specific, dedicated work [on the subject] and reveals the shortsightedness of the publishers of the 1930s who did not commission such a work from him after reading The History of the Russian Revolution. Page after page, a brilliant observation, dazzling does of humor, or a summary shows what has been lost because of this gap.7Pierre Broué, “Trotsky et la Révolution française” (“Trotsky and the French Revolution”), Cahiers Leon Trotsky 30 (June 1987).

I cannot help but agree with Broué’s disappointment.

Conclusion

When we find the historical analogies in Trotsky’s work, we realize he wasn’t out to “force” them to “coincide” with what was happening in the Russian Revolution. Instead, because he saw himself as a protagonist of the proletarian revolution, he was seeking points of support — in much the same way that Galileo did when he “killed” God. In The Lessons of October, Trotsky concludes that:

Had we failed to study the Great French Revolution, the revolution of 1848, and the Paris Commune, we should never have been able to achieve the October Revolution … we went through this “national” experience of ours basing ourselves on deductions from previous revolutions, and extending their historical line.8Trotsky, The Lessons of October, chap. 1, “We Must Study the October Revolution” (1924).

Victor Serge9Translator’s note: Victor Serge (1890–1947) was a Russian revolutionary writer who joined the Bolsheviks in Petrograd in early 1919 after having been an anarchist. He was a critic of Stalin and revolutionary Marxists until his death. tells how some of the Bolsheviks wanted to “conduct a trial of the last Tsar before the proletarians of the Ural” in which “Trotsky was to take the role of public prosecutor”10Victor Serge, Year One of the Russian Revolution, chap. 8, “The July–August Crisis” (1930). — just as Robespierre had done against the king of France — to address the crimes he had committed against the Russian people. But although other circumstances changed the fate of the royal family, it is worth noting that it was Lenin who erected in the land of the soviets the only statue of Robespierre in all of Europe.

The Great French Revolution left a deep mark on the thinking of the founder of the Red Army, Leon Trotsky. He explains that the sans-culottes defeated the monarchy not only because of class hatred, but also because of the political and moral conviction behind their objectives. He also explains this in his military writings: that the imperialist bourgeoisies could not understand how in Russia, a country devastated by World War I, the workers and peasants had not only taken power but also built an army of 5 million souls and defeated a siege by 14 imperialist armies, emerging victorious. When Trotsky founded the Red Army, he explained to the soldiers that they were now the vanguard of the world socialist revolution. In the trenches, the soldiers fought through mud, blood, and snow, but they kept going because they knew they were fighting to change world history, and political and moral conviction was as important as the gun.

Both the French and Russian revolutions changed the history of the world and deserve to be studied in preparation for the triumph of the 21st-century revolutions. That is not a utopian expectation; what would be utopian is to believe that there will never be another revolution in the world. That’s what King Louis XVI thought, until his head met the edge of the guillotine.

First published in Spanish on July 14, 2015 in La Izquierda da Diario.

Translation by Scott Cooper

Notes

| ↑1 | Translator’s note: The reference is to Trotsky’s autobiography, in which he mentions D. Sverchkov’s description of their imprisonment together. Trotsky quotes Sverchkov’s memoir At the Dawn of the Revolution. See Trotsky, My Life, chap. 15, “Trial, Exile, Escape.” |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Trotsky, Results and Prospects, chap. 3, “1789 – 1848 – 1905.” |

| ↑3 | Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, chap. 1 (1852). |

| ↑4 | Translator’s note: Trotsky refers to it as “a new double sovereignty” that “with increasing boldness contests the power with the official representatives of the national bourgeoisie.” |

| ↑5 | Translator’s note: The sans-culottes (French for “without breeches”) were the lower-class commoners of late 18th-century France who comprised the militant popular partisans of the revolution. The term, which was used to distinguish these pants-wearing urban laborers from the nobility and bourgeoisie who wore fashionable silk breeches, was coined by a French general and used derogatorily, but came to be embraced by the revolutionary masses. |

| ↑6 | Trotsky, The History of the Russian Revolution, chap. 11, “Dual Power.” |

| ↑7 | Pierre Broué, “Trotsky et la Révolution française” (“Trotsky and the French Revolution”), Cahiers Leon Trotsky 30 (June 1987). |

| ↑8 | Trotsky, The Lessons of October, chap. 1, “We Must Study the October Revolution” (1924). |

| ↑9 | Translator’s note: Victor Serge (1890–1947) was a Russian revolutionary writer who joined the Bolsheviks in Petrograd in early 1919 after having been an anarchist. He was a critic of Stalin and revolutionary Marxists until his death. |

| ↑10 | Victor Serge, Year One of the Russian Revolution, chap. 8, “The July–August Crisis” (1930). |