A lot has been written about the Communist International, a global revolutionary organization that was founded by Lenin in 1919 and dissolved by Stalin in 1943. The Comintern had up to 80 national sections, alongside internationals for youth, women, unions, peasants, and others. The experience of this “world party” offers numerous lessons for revolutionary socialists today.

Books on the Third International tend to focus on its leaders and its congresses: Lenin and Trotsky fighting for the united front in 1921, and similar episodes. A collective of dedicated historians has spent decades publishing documents from all the Comintern’s meetings in English.

The retired history professor Brigitte Studer, with a distant background in Switzerland’s Trotskyist movement, offers a new approach to Communist history: her book, published in German in 2020 by Suhrkamp, with a new English translation by Verso hitting shelves now, looks at the “travelers of world revolution.”1This review is based on the German edition of the book. In other words, she focuses on the thousands of professional revolutionaries who kept the International running. These polyglot activists earned very little money, traveling from country to country, often illegally, doing myriad jobs, and sometimes ending up in prison. They converged at different hotspots of world revolution: Moscow 1920, Berlin 1923, Shanghai 1925-27, Madrid 1936. Theirs is the story of the Comintern as a workplace.

The book names 320 individuals, but focuses on the stories of roughly two dozen, in a kind of transnational collective biography. Some of these people are the unknown worker bees dedicated to routine tasks: the typists, couriers, translators, encryptors, and others. Studer has done some original research about Comintern employees in Shanghai during the revolution of 1926-27. They ran the underground apparatus needed to maintain links between Chinese revolutionaries and the headquarters in Moscow, and when they were arrested, an international campaign tried to get them back to Switzerland. But with a few exceptions, this book is not the story of such virtually nameless proletarians. It might be possible to write such a book based on the archives in Moscow, but that would require at least a hundred researchers.

Studer’s main protagonists are actually quite well-known activists who published their memoirs, such as the Indian revolutionary M.N. Roy, his American wife Evelyn Trent-Roy, the German propagandist Willi Münzenberg, his partner Babette Groß, the German Stalinist Heinz Neumann, his partner Margarete Buber-Neumann, the founder of the German communist intelligence service Karl Gröhl / Retzlaw, the Swiss expert for Latin America Jules Humbert-Droz, and a few others. These were not top-tier leaders, but not exactly rank-and-file activists either — they were more like middle management.

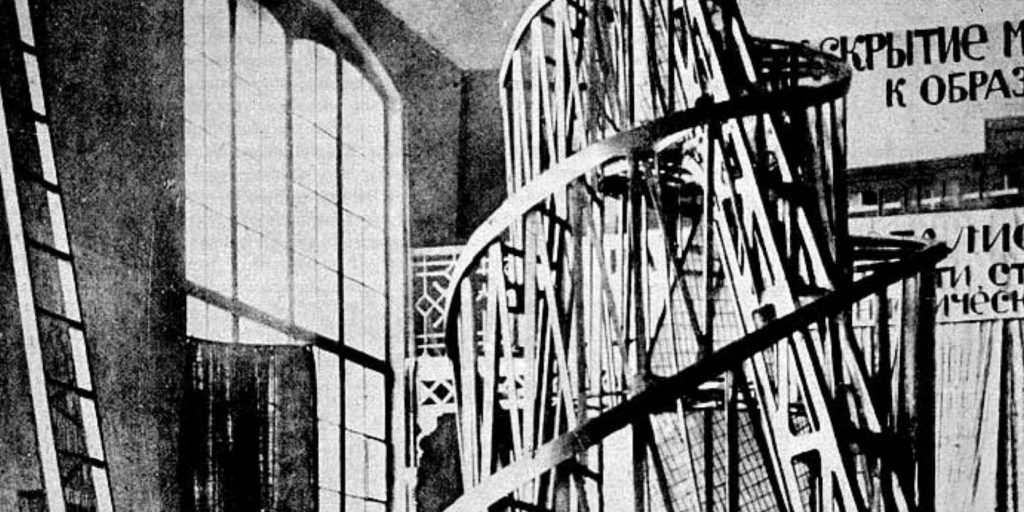

Studer has not only supplemented their autobiographies with material — including excellent photos — from the Comintern archives. Even for history nerds like me who have read most of these memoirs, Studer has done a great service by weaving their stories together and showing how they intersected in different international campaigns.

Women played important roles at all levels of the Comintern, making up about a sixth of all employees, but Studer shows how they could be doubly excluded, once from leadership roles in the movement and again from the history of the movement. Often, a courageous and groundbreaking revolutionary like Trent-Roy is only remembered as the wife of so-and-so, and Studer works to correct that.

For a Berliner like me, a particular interest is seeing how the German capital served as a “second global center of international communism” next to Moscow. Before power was handed to the Nazis in 1933, Red Berlin served as a gateway between the Soviet Union and the capitalist world. It was from an office in Berlin’s center that Willi Münzenberg coordinated international anti-colonial campaigns with African communists like Joseph Ekwe Bilé. While the book gives a good overview of revolutionary movements across the Eurasian double continent, there’s unfortunately less of a focus on the work of the Communist International in Latin America and Africa, where many of these same “Cominterians” were active.

The employees of the Comintern often experienced the contradictions between their revolutionary ideals and the frustrations of a low-paid job with lots of overtime — compounded if they had to live underground without much of a social life. Communists were willing to take on incredible burdens in the struggle for universal human emancipation. But many of them were ultimately broken by the counterrevolution inside the Communist movement: the rise of Stalinism. Some were physically liquidated: a third of the 320 people mentioned in this book suffered violent ends. Many more were morally broken: of the numerous figures mentioned here who were active in the Comintern in 1920, not a single one was still around when it was dissolved in 1943.

Heinz Neumann, for example, was once a dedicated Stalinist who led the Communist Party of Germany (KPD). Neumann was responsible for the disastrous “third period” policy of opposing any united front against fascism. As Stalin’s Great Purges progressed, with horrendous and preposterous accusations against revolutionary leaders, Neumann slowly lost his faith in the “man of steel” he had once admired. After he finished a job translating transcripts of the Moscow Trials, he informed his partner he was going to kill himself. He couldn’t stomach the lies against Old Bolsheviks, but also lacked the strength to speak up against them. In the end, he didn’t commit suicide — he was was shot by Stalin’s secret police, alongside so many exiles at Moscow’s Hotel Lux.

In such a thorough look at Comintern history, it is surprising that Studer offers no theoretical framework for understanding Stalinism. She describes Stalin’s murderous bureaucracy as a “human resources department of a special kind” going through a Weberian process of bureaucratization. We would be hard-pressed to find any other HR department that murdered most of its founders and employees. This book offers ample evidence that Stalinism did not represent the logical development of Lenin’s legacy — it was the radical negation of the ideas that inspired the October Revolution. Proof of this is the Comintern itself: while Lenin fought to organize a global revolutionary movement, Stalin destroyed it.

Rumors indicate that a monumental history of the Communist International by French Trotskyist historian Pierre Broué is finally going to appear in English translation in the not-to-distant future. Studer’s work is full of interesting stories, Broué can explain why things happened the way they did.

Brigitte Studer, Travellers of the World Revolution: A Global History of the Communist International (London: Verso, 2023), 496p, $39.95.

Notes

| ↑1 | This review is based on the German edition of the book. |

|---|