Parasite has broken a Hollywood taboo — which has lasted 90 years — by winning the most coveted award, the Oscar for Best Picture, even though it is not in English, becoming the first non-English-language film to do so. The Academy’s hyperfocus on English-language films is to be expected if we consider that the Academy Award was created to promote not cinema in general but Anglo-American cinema specifically (with all its ideological baggage). Otherwise, how else can one explain the existence of a specific (and minor) award for Best Foreign Film, which Parasite also won? The event deserves some reflection to understand why this film is so special.

Even before it won big at the Oscars, Parasite had already enjoyed wide public and, above all, critical acclaim around the world. What struck many reviewers, beyond the film’s appreciable aesthetic aspects, was its courageous representation of class struggle in the interaction between a very poor and a very rich family. The members of the poor family, who experience a terrible life of misery, on the margins of everything, take advantage of a series of circumstances to be hired by the rich family as tutors, drivers, housekeepers. The poor family’s “hunger” is so deep and ancient that, to maintain their relative privilege, they are willing to hurt and kill other competing workers, before killing — almost by chance — their master.

Considering that class conflict has largely been absent from the cinema of the last 40 years — to the point that pronouncing the word “class” or “proletariat” is almost unheard of — one can understand the positive astonishment of many critics. Excited by the novelty (wow, class struggle!), however, critics have ended up neglecting important elements of the film. They have dwelled on the representation of the pitiful state of the workers’ class consciousness, on the fact that the film shows how evil the bosses are, and on today’s extreme inequalities.

You might also be interested in: Class, Morality, and Capitalism in ‘Parasite’

All in all, we share these reflections. Indeed, these elements are present in the film, but they were not put there to be explained to the proletariat: the film does not speak to them; it addresses the bourgeoisie. This was revealed by the director himself at the Oscars, when, after having vaulted the golden statues into the air, he declared, “Between rich and poor, neither good nor bad.” Bong Joon-Ho felt the irrepressible need to publicly exclude a moralistic view of his film. In doing so, he ironically confirmed his moralistic viewpoint (which is ultimately classist): equating the superpoor family’s reprehensible behavior with the routine and gratuitous violence of the rich family, who are the primary cause of the former’s miserable and precarious condition. Bong Joon-Ho is not alone in this. It has now become fashionable to equate the behavior of the truly violent with that of those who react to violence, fascists with the partisans of the Italian Resistance… the false equivalence of fascism and communism has practically been institutionalized.

Parasite speaks to the bourgeoisie because it is the filmic representation of their greatest fear, that the poor rise up and the rich fall down, as billionaire Johann Rupert, owner of Cartier, confessed in 2015 at the Financial Times Business of Luxury Summit in Monaco. The thought of a social upheaval grips the bosses; the hatred of the proletariat keeps them awake at night. To put it in Rupert’s words, they ask themselves incessantly, especially in these last years of endless crisis, “How is society [i.e., the bourgeoisie] going to cope with structural unemployment and the envy, hatred and the social warfare?”

All the bourgeoisie’s moves since the crisis of 2008 have been aimed at preventing, containing, managing, and redirecting the hatred of the proletariat. Ricardo Antunes and Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen are right when they define the current international reactionary movements in the world (led by Trump, Bolsonaro, Orban, Le Pen, Putin, Salvini, et al.) as a “preemptive counter-revolution.” This is not to say that the world is now in a (pre-)revolutionary situation, but that reactionaries want to prevent any desire for insurgency, since the bourgeoisie understands — at the moment much better than the proletariat — that capitalism has definitively lost its magic propulsive force, that is, the illusion that one can get a better life by working. The number of the working poor in the world, of those who work 12 hours a day but cannot feed or clothe themselves, is growing exponentially. In the absence of the great illusion, what remains? The objective truth of an existence made up of domination, hierarchy, racism, and violence, not to mention the definitive destruction of the biosphere. The veil has been swept by the storms of the crisis, and the masters risk appearing for what they are: vampires and serial torturers. This is what disturbs them and puts them on alert.

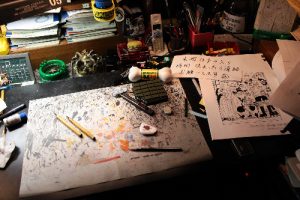

Parasite has translated the universal anguish of the masters of the world into images and language. And Bong Joon-ho has done so by staging the cruelest and most disturbing class relationship that exists, that between masters and domestic workers. Here the director’s merit must be acknowledged: his sociological outlook is particularly refined (the director, among other things, holds a degree in sociology). Harriet Martineau, one of the most important mothers of sociology, explained back in 1838 how domination was the figure of domestic work:

The peculiarity in the life of domestic service is subjection to the will of another… A servant enters a family for the very purpose of fulfilling the will of the employer… How troublesome and fundamentally vicious an arrangement that is, becomes apparent when we consider the difficulty of settling where this obedience to another’s will is to stop.

There is no work that better reveals the intensity of class tension between master and worker. The orders of the master, who is near and can be felt and touched, arouse deep emotions and feelings in the worker, invoking a depth of feeling not easily found in other jobs, in which the master is distant, invisible, and untouchable. The close social distance with the master transforms the workplace into a meeting place of hidden causes, of impulses, but obviously also of social and economic causes. The class tension here is composed of stimuli that come from within the body and the environment. The masters feel this extreme tension developing inside their homes, and for this reason they very often try to hide it even from themselves, to mask it, to remove it. It is no coincidence, in fact, that one hears phrases like “She sued me for her lack of social contributions, even though I treated her like a sister”; “My housekeeper and I are friends, I went to her son’s baptism”; “With Maria we often go out to dinner, I gave her some of my clothes.”

Within the limited space of the house, there arises a powerful hatred among the domestic workers, because they see the bosses in their most intimate dimension and feel their deep contempt and racism.

All this emerges very well in one of the film’s emblematic dialogues, when the Park couple, lying in the dark on the living room sofa, talk about the disgust they feel every day when they smell their servants (money does not stink, but rags to), and this excites them sexually:

Mr. Park: Where does this smell come from?

Mrs. Park: What smell?

Mr. Park: Mr. Kim’s smell.

Mrs. Park: Mr. Kim?

Mr. Park: Yes.

Mrs. Park: I don’t know what you mean.

Mr. Park: Really? You must’ve smelled him. That smell in the car, how can I describe it?

Mrs. Park: The smell of an old man?

Mr. Park: No, no, that’s not it. What is it? Like an old radish. No, you know when you boil a rag? It smells like this.

The stench that the Parks smell is coming from under the living room table, where driver Kim, and his whole family, hear the bosses’ words (and disgust). This physical closeness between bosses and domestic workers creates a magnetic field that intensifies the bosses’ neurosis (already created by market competition) and causes their nightmares, their terrible fear of being slaughtered at night by the servants. Paradoxically, it is in their homes that they feel less protected, more exposed to the hatred of the exploited. For the space outside is always the state with all its ideological-repressive apparatus, but in the home they are vulnerable and in close contact with those who hate them.

That the film speaks to the bosses can also be seen in the dystopian ending: the poor family man ends up walled up alive in the villa of the rich (now abandoned), his daughter dies, and his wife and son are tried and then condemned to return to their extreme misery. The son, desperate and traumatized, will continue to daydream of a rich man’s future. The film is an apocalypse with no way out for the poor family. The horizon assigned to them is one of resignation to domination and exploitation. That’s all there is to it.

The film recounts the nightmares of the masters in the contemporary world, and, although they are expressed in Korean, the masters of the Academy have recognized them. One can thus understand the general excitement for a film that puts the conduct of masters and workers on an equal footing, creating a deliberate cognitive and emotional confusion in the spectator. But Parasite has only one important message, and this message is for the bourgeoisie of all latitudes: soon the extreme and brutal hatred that you have put into circulation will come back against you. Soon the proletarians will wake up from their sleep and “make us fall.” From a psychoanalytic point of view, one could say that this film mirror’s the bourgeoisie’s unconscious desire for punishment.

Let’s satisfy that desire!

Originally published in Italian on La Voce delle Lotte on February 18, 2020.

Translation: Giacomo Turci