Prisons, like police, exist to repress the working class and Black and Brown people. They are used to punish activists and revolutionaries, put the most oppressed sectors of the working class “in its place,” and create — along with the unemployed — part of the reserve body of labor that is low-cost, compulsory, and fractured from the remainder of the working class. The prison system has developed into what is called the “prison industrial complex” — a vast network of for-profit institutions that work with and for major corporations through subcontracted work for upkeep, construction, food distribution, and so on. This system is the largest it has ever been, and is highly concentrated in the capital of imperialism, the United States.

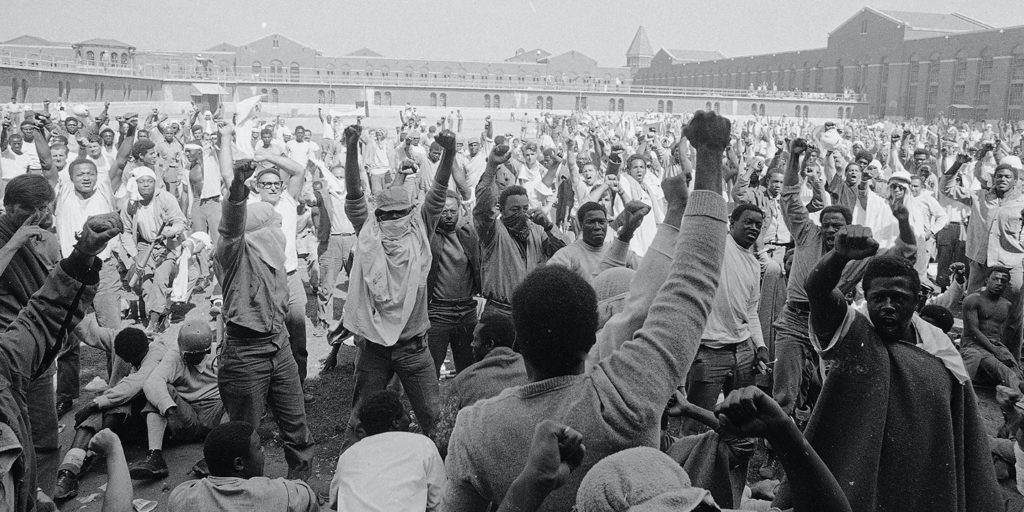

Often, the incarcerated working class, especially incarcerated Black and Brown victims of the system, fight back. Against the behemoth that is the prison system, imprisoned people have organized hunger strikes, labor strikes, and rebellions. One of the most notable rebellions is the 1971 uprising at the Attica Correctional Facility, in which an organized body set out to realize clear political goals. The struggle of the Attica fighters that began 49 years ago today lives on in more contemporary prison uprisings and strikes, campaigns to free political prisoners, and growing movements to abolish the police completely.

Backdrop to the Attica Rebellion

Attica Correctional Facility is a maximum-security prison located in the small town of Attica in upstate New York. In 1971, the conditions there were profoundly horrible. In her book Blood in the Water,1Heather Ann Thompson, Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Aftermath (New York: Pantheon, 2016). Heather Ann Thompson details the conditions in which the incarcerated people of the time lived. They were given monthly allotments of toilet paper insufficient to last; kept in cell blocks that were freezing cold or sweltering hot; allowed one shower per week; and had their reading material censored. There were only two doctors responsible for more than 2,000 people, those doctors were often apathetic to the prison population when serious concerns were raised. Patients were typically dismissed with nothing but aspirin, and those who could not speak english were almost completely ignored.

The incarcerated population at Attica were mostly Black and Puerto Rican people from New York City from poor working-class backgrounds. Visits from their families were unaffordable, between the cost of a bus ticket and missing a day’s work. That left those incarcerated in a difficult situation: their families could not afford to see them and provide in-person emotional support, and those same families could not afford to support them financially so they could get needed supplies such as additional toilet paper and clothing. They often had nothing to supplement the slave wages they were paid in the exploitative jobs they were forced to work: the most someone could receive in a day was $2.95, but on average the daily pay was about 40 cents.

Even when those who were incarcerated were finally approved for parole, they would not be allowed to leave the prison until they could prove they had a job waiting on the outside. Parolees would be forced to sit all day at a prison phone making calls for which they had to pay with their commissary money, working through a phone book to call different places looking for work. Jobs were hard to come by, because those who’ve served time in prison are discriminated against — in addition to discrimination for being Black or Latinx.

The uprising at Attica took place during the Black Power movement, a time of heightened anti-capitalist sentiment and revolutionary activity, particularly around Black struggle. It was during this period that the Black Panther Party emerged, with Black people organizing themselves against racism, capitalism, and the state, which they saw as one of the greatest purveyors of racism. A core demand in the Black Panther Party program was the immediate release from prison of all Black people in the United States — because no Black person ever received a fair trial by the racist state.

With all of these factors in play, including excessive brutality and continued abuse by prison guards, and informed by the revolutionary spirit and rhetoric of the time, those incarcerated in Attica decided to rebel against this entity of state violence and demand their basic democratic and material rights.

The Uprising and Its Brutal Suppression

On September 9, 1971, thousands of people incarcerated in Attica seized various sections of the prison, captured weapons and used those they had fashioned themselves, and took guards as hostages. They issued a manifesto with a list of political demands, both democratic and material. They demanded the right to assemble free from brutalization, as well as demanding legal representation, an end to media censorship, and an end to racial and political persecution.

Their material demands included adequate medical staff and facilities available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Beyond issues of health and democratic rights, those incarcerated believed themselves to be workers whose labor was being exploited to profit the state and its corporate partners. With this, the workers of Attica also demanded that industries provide vocational training inside the prison and that those incarcerated be allowed to organize unions. They demanded that their work be subject to all federal and state minimum wage laws and that their compensation be enough to support not only themselves while in prison but also their families back home.

The uprising lasted for four days and captured the attention of the world. Then, on the morning of September 14, it was violently suppressed. New York’s governor at the time, Nelson Rockefeller, sent in State Police. The State Police were beyond ruthless. They shot and killed 29 of the incarcerated (and some of their guard hostages) and injured 85 others. There was no ultimatum about surrendering; the cops simply removed their identification badges so they couldn’t be held accountable for the violence and began shooting. In the aftermath, prison authorities tortured, burned, and sexually abused those who had taken part in the rebellion.

The violent suppression of the Attica uprising amplified the “tough-on-crime” policies that persist today and that dehumanize incarcerated people and people of color in particular. It was a prime example of how the state responds to Black and Brown people fighting for their liberation. At the time, President Richard Nixon hailed the attack, and Rockefeller told him it was a “beautiful operation.”

We Choose Perseverance to Combat State Violence

Today, the spirit of the Attica rebellion lives on — despite that, the state continues to use violence and prisons to suppress the working class and people of color. The United States leads all countries of the world, by far, in the number of prisons and incarcerated people. Those numbers have expanded tremendously since the end of the Attica rebellion. However, just as in 1971, the fightback continues.

In 2016, a wave of prison strikes occurred across the United States. In the spirit of the Attica Rebellion, imprisoned people in nearly half of U.S.states took part in a general strike. An estimated 24,000 to 72,000 people took part — making it, in either case, the largest prison strike in U.S. history.The struggle against prison exploitation, for democratic rights for incarcerated people, and for decent wages, is class struggle.

More recently, with the Covid-19 pandemic, prisons have been hit hardest because of unsanitary conditions and the inability to practice social distancing. At a Lansing, Kansas prison, incarcerated people destroyed offices and windows and set fires across the facility, demanding to be transferred either to house arrest or be given personal protective equipment (PPE) and ample cleaning supplies.

Coronavirus-related prison uprisings are not limited to the United States. In the Buenos Aires neighborhood of Villa Devoto in Argentina, those in jail set mattresses ablaze and took to the roof to hurl objects at guards. “We refuse to die in prison,” they insisted, and demanded protective equipment to protect people from the virus and that judges reevaluate their cases so inmates could be released.

State repression and the abuse of incarcerated people persists well beyond the borders of the world’s largest carceral state, the United States. Political struggle against the prison apparatus is a global phenomenon.

Unity of the working class is paramount if we are to rid the world of prisons. The working class is the revolutionary component that will destroy the carceral institutions that maintain capitalism, but it can happen only if the working class consolidates its strength and fights back as one fully formed fist. We need to include the hyper-exploited working class in prisons in the larger movement for socialism, and the working class outside of prisons must support class-struggle uprisings inside prisons.

The state always chooses violence against the working class and oppressed people and the state’s victims continually fight back with ferocity and a militant political perspective. Though the state mercilessly suppressed the Attica uprising, it has never been able to kill the spirit that started the rebellion! The struggle will continue until the eradication, by the working class and its oppressed sectors, of prisons, the state, racism, and capitalism.

Notes

| ↑1 | Heather Ann Thompson, Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Aftermath (New York: Pantheon, 2016). |

|---|