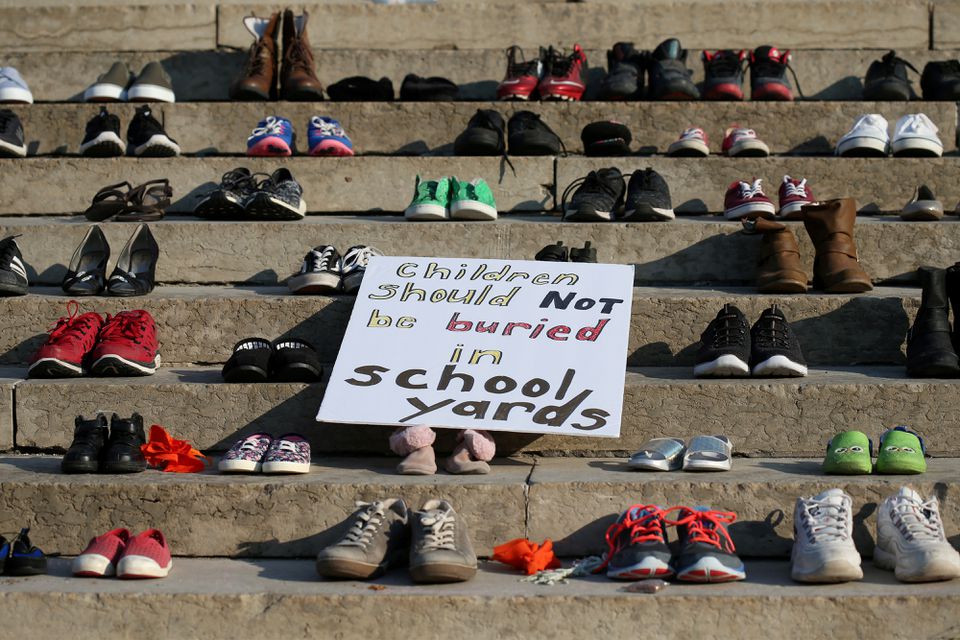

Less than a month after the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation’s uncovering of 215 unmarked graves of indigenous children at Kamloops Indian Residential School, another harrowing discovery revealed an additional 751 unmarked graves at the site of the Marieval Indian Residential School in Saskatchewan by the Cowessess First Nation. The Federation of Sovereign Indigenous First Nations is continuing their ongoing search for the bodies of children who died while attending Canadian residential schools throughout their devastating hundred-year duration. According to the Anishnabek Nation, it is estimated that “over 150,000 First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, between the ages of 4 and 16 years old, attended Indian residential schools in Canada”. In the United States, estimates range in the hundreds of thousands of Native American children.

In addition to understanding their horrific conditions, it’s also essential to evaluate the role that residential schools, such as those at Kamloops and Marieval, played in the realization of the colonial projects that would become Canada and the United States. Indigenous peoples in North America and around the world are still fighting both the historical legacies of genocide, as well as ongoing assaults on their lands and cultures.

While acknowledgements and truth finding are essential elements for community healing, we have to recognize that our capitalist governments will never tell the truth, nor fundamentally change their mission to pillage and exploit. Thus, apologies from the state, religious institutions, and corporations will never be more than lip service under a capitalist framework. The fight for indigenous rights and self-determination is deeply entangled with the fight to take down the forces of capital.

The Roots of Capitalism

Before European contact, First Peoples existed on the continent of North America for thousands of years. The six large groups of First Nations in what is now Canada have been delineated by historians according to the environments they inhabited: Woodland First Nations, Iroquoian First Nations, Plains First Nations, Plateau First Nations, Pacific Coast First Nations, and First Nations of the Mackenzie and Yukon River basins. Inuit peoples inhabited, and continue to inhabit, the Arctic regions of Greenland, Canada, and Alaska. Each group had distinct lifestyles and methods of social organization according to the living conditions available to them by their natural environments. Whereas Iroquoian and Pacific Coast First Nations were able to establish permanent residences and in some cases council-based political systems, Plains First Nations organized themselves according to their migratory lifestyles. First Nations and European fishermen from many different countries engaged in informal trade for about a hundred years by the early 1600s. At that point, larger groups of Europeans, having heard stories of the vast wealth of resources and “untouched” land, came to see for themselves.

By the mid eighteenth century, tensions were high over which colonial European power would establish dominance over what was considered to be the “New World.” The relationship between the First Nations and the British was founded upon commercial and military interests, as First Nations were critical to the British victory over the French in the Seven Years War of 1756-1763. Early on, the British established the Indian Department to coordinate alliances with First Nations. After the war, the British Crown pressured the French-aligned First Nations to sign peace treaties so that the British could maintain its economic dominance over the lucrative fur trade. To establish a relationship of alliance, the Royal Proclamation of 1763 put in place a firm western boundary, beyond which no settlement or trade would be allowed without the express permission of Indian Department.

After Britain recognized the independence of the United States in 1783, thirty thousand Loyalist refugees came to Canada and wanted land. In addition, First Nations who supported the British during the war were also dispossessed, their lands given to the United States in the Treaty of Versailles. The Indian Department brokered land surrenders with the First Nations around the St. Lawrence River and Great Lakes, and created two reserves for First Nations — one at the Bay of Quinte and the other along the Grand River. The British were careful to maintain peaceful relationships with the First Nations. As their numbers were so great compared to the settlers’, their alliance would be needed in the case of war with the new colonial state to the south. This would soon materialize in the War of 1812, when Tucemseh’s Confederacy and the Iroquois would support the British in defending what is now southern Ontario against a U.S. invasion.

In the period following the war, more European settlers came to the burgeoning colony demanding more land. Now that the number of settlers were growing in relation to the indigenous people, the Crown began to regard the First Nations, rather than allies, as impediments to growth and expansion. The Crown began to encroach upon the remaining territory controlled by First Nations, pressuring them to sign greater numbers of land surrender treaties.

The rapid transformation of the way of life of First Peoples can be traced back to the capitalist exploitation that had taken root by this historical moment. The Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), a fur trading monopoly in the region, and its rivals capitalized upon the ravenous desire for animal pelts in Europe, leading to increasing exploitation of the land’s natural resources and the indigenous people who were skilled at harvesting them. In turn, indigenous communities became flooded with European products such as guns, knives, and iron products, increasing their dependence on these goods. The invasive seeds of capitalism had begun to germinate.

The Assimilation Era

In the midst of the changing power dynamic and in search of a way to justify its colonial exploits, a new philosophy was emerging with respect to the role of the British Empire toward the Indigenous people it subjugated. The view held that the British lifestyle was superior, and the Crown was therefore obligated to “civilize” the indigenous people over which it ruled, from the Aboriginal people of present-day Australia to the First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people of present-day Canada. This “civilizing mission,” which centered on sedentary agricultural practices and conversion to Christianity, was the foundation for the assimilation era that was to follow.

Throughout the first half of the nineteenth century, more legislation was passed that consolidated control over land in the hands of the Crown (Crown Lands Protection Act of 1839) and incentivized First Nations to give up their traditional lifestyle (Gradual Civilization Act of 1857). In 1867, the British North America Act established the independent Dominion of Canada, which opted to maintain the centralized policy over First Nations in the new country. The government of Canada bought an enormous chunk of land previously controlled by the Hudson’s Bay Company, which expanded its reach westward. In the colony of British Columbia, the policy was marked by a persistent refusal to acknowledge Aboriginal land title.

The Indian Act of 1876 was the legislation that most significantly shaped Canadian policy toward First Peoples in the assimilation era. It granted greater authority over the Department of Indian Affairs, which would establish itself as a “guardian,” regulating First Nations land, money, and resources and carrying out its “civilizing mission.” Throughout its many amendments, the Indian Act made further strides to compel First Nations to give up their traditional ways of life, established automatic enfranchisement upon the receipt of a college degree, and forbidding Aboriginal land claims without the permission of the Department of Indian Affairs.

Boarding schools constituted a major part of the Dominion’s strategy to assimilate and dispossess First Peoples of their land and culture. Key to the assimilation project were the Indian Department, which already possessed a relationship with the First Nations, and Christian missionaries, eager to spread their religion to the indigenous population. The majority of residential schools were designed and carried out by churches with the financial support of the Crown, and later the Dominion of Canada. In light of the recent discovery at Marieval, the Catholic Church is getting particular heat for its role in perpetuating the deadly boarding school policy. This should not be at the expense of forgetting the role of Anglican, Methodist, Presbyterian, and United churches in the atrocities of boarding schools.

The words of Richard Henry Pratt, an American general who oversaw the first Indian Residential School established in Carlisle, Pennsylvania in 1879, came to embody the credo of boarding schools throughout their tragic duration in North America: “Kill the Indian, Save the man.” Pratt, and others in the “Friends of the Indian” movement, regarded boarding schools as a humane alternative to the dominant settler view that Indigenous people were subhuman and unable to learn.

Yet it is clear that this paternalistic scheme was far from humane, which sought to “assimilate” and “civilize” Indigenous people through linguistic and cultural deprivation. New boarding school arrivals were first shorn of any outward signs of their cultures — long braids worn by boys were cut off and traditional clothing replaced by standard uniforms. They were then christened with new white names and forced to learn European table etiquette. They were taught English or French at the expense of their native tongues, which, for the children at Marieval, would be Cree. Punishments for uttering a word of their languages ranged from haircuts to beatings and meal deprivation. The “education” sought to instill European beliefs and values while ensuring compliance with the capitalist system, drilling the importance of “private property, material wealth and monogamous nuclear families.”

Indigenous children were exploited for their labor. In many residential schools, the stated goal was to provide the vocational and social skills used to obtain a job in mainstream society. Yet the real motive for their “vocational training” was The Department of Indian Affairs’ demand that schools be self-sustaining so that they could take in more students with no additional cost to the state. Many residential schools adopted a half-day system, where half the day was allotted for academics and the other for “industrial school.” Children were taught and expected to perform the gender-normative roles of a European household — girls were assigned to mend clothes, do the laundry, cook, and clean while boys were expected to perform the manual labor that the school required, including growing the food, farming the land, and tending to animals. Carlisle developed a “placing out” system in which children were sent to work on the farms and in the homes of white families to “learn the values of work and the benefits of civilization.” Residential schools did not only destroy language and culture; they also served to exploit the labor of children.

Accompanying the indoctrination and exploitation at residential schools was near-ubiquitous physical, emotional, and sexual abuse. Survivor testimony suggests that in many schools, sexual and physical abuse rates were higher than 75 percent. Unsanitary conditions were widespread, and many children died of disease. Others died in their attempts to run away. Children resisted their “education” by maintaining intimate friendships, secretly speaking to each other in their natives tongues or teaching them to children who never learned.

Residential Schools in the United States

At the time the boarding school policy was established in the United States, the federal government was well into its project of establishing prisoner-of-war camps that would later become known as reservations. However, officials needed a way to prevent collective action against the United States. The Dawes Allotment Act of 1887 and the boarding school system constituted a double-pronged attack on the lifestyle and sovereignty of Native people in the U.S. The Dawes Act sought to break up tribal land into individual plots for standardized farming. The plots were mere fractions of the land they previously inhabited, and were often unfarmable. Through the Dawes Act, the U.S. government stole over 90 million acres of tribal land and sold remaining plots to white homesteaders.

Recruitment to boarding schools thus also served to maintain control over nations resisting colonization. They took captive the children of leaders to ensure “good behavior.” The U.S. Department of War sent Pratt to the Dakota Territory to recruit some of the first students for Carlisle, which included children of the Oglala Sioux and Brule Sioux tribes, who were in the latter half of a forty-year fight to retain their land and way of life during the Sioux Wars. Recruitment to boarding schools was more than a paternalistic effort to assimilate Indigenous people — it was about maintaining control.

Recruitment took various forms as time went on. Federal officials told indigenous leaders that boarding schools were a way for their children to learn English to better be able to serve the interests of the tribe. More often than not, children were forcefully kidnapped. In the late 19th century, the government enacted laws that compelled mandatory school attendance for all indigenous children. Because of the remote locations of many communities, sending one’s children to boarding schools was often the only way to comply with the law. The legislation enabled federal officials to forcibly remove Indigenous children from their families and send them away.

Throughout the assimilation era, abductions were met with fierce resistance. When government officials came to take away their children, some parents would send their children to play hide-and-seek to evade their kidnappers. When they had the means, some families would leave their homes for days or weeks at a time while round-ups took place. In the early twentieth century, the Teetł’it Zheh responded to the death of the chief’s daughter at a residential school by refusing to send more children at the threat of imprisonment, and petitioning the government to build more day schools in their community. One of the political organizations created in response to this tragedy evolved into what is now the Assembly of First Nations. In another act of resistance in 1894, seventeen Hopi men were sent to the U.S. military prison in Alcatraz for refusing to allow government officials to take their children away. Still, many Indigenous were coerced into enrolling their children under threats of violence, imprisonment, and withdrawal of rations.

Not Ancient History

Many elders remember the heartache of boarding schools viscerally — abducted from their families, compelled to forget their languages through force, and exposed to physical, sexual, and psychological abuse. To further isolate children from their culture, family visits were limited, vacations were rare, and even letters from families were confiscated. Some of the most prominent leaders of the American Indian Movement (AIM), such as Dennis Banks, who attended boarding schools recall the void left by their time there. For many, the return home proved to be heartbreaking, no longer able to connect with their parents through a language they were forced to forget. The language theft catalyzed by the boarding schools is one of the most destructive remnants of this era.

Boarding schools are not the only way that indigenous families were — and continue to be — broken up. The foster care system is a way that the assimilation policy of boarding schools survives into today, even after their final doors have closed. Nunavut Member of Parliament Mumilaaq Qaqaqq asserted, “foster care is the new residential school system,” raising the vastly disproportionate rates of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis children in the foster care system in Canada. According to the 2016 Census, Indigenous children account for more than 50 percent of those in foster care but make up less than eight per cent of the child population.

It’s a similar story in the United States. By the 1970s, “…research found that approximately 25% to 35% of all Native children in the U.S. were being placed in foster homes, adoptive homes, or institutions, and 85% of these children were being placed outside of their families and communities, even when fit and willing relatives were available to care for them.” There continue to be alarming disparities between Native and non-native children removed from their families in the foster care system. It wasn’t until the passage of the 1978 Indian Child Welfare Act that parents gained the legal right to deny their children’s placement in off-reservation schools, yet Native American children are still disproportionately funneled into the foster care system. Health, educational, and economic disparities between native and non-native populations continue to be egregious. The Dawes Act continues to undermine autonomy by creating a “checkerboard pattern” of land ownership on reservations, making it nearly impossible for Native Americans to control their own economies despite their status as sovereign nations. In Montana, COVID mortality rates were nearly 4 times higher for Native Americans compared to the state’s white population. Among many factors, these outcomes are a result of vast resource deficits, poorly maintained physical and communication infrastructure, and the effects of years of compounded cultural deprivation.

Ongoing Assaults, Ongoing Resistance

The boarding school era of Indigenous genocide is far from ancient history. In Canada, the Marieval Indian Residential School was one of the last to close its doors in 1997 after 98 years of operation. While it is possible to estimate the number of deaths, abuse victims, and stolen languages, the true extent of the trauma and erasure throughout the some 150 years of the assimilation era is impossible to measure.

This is more than a “dark and shameful chapter” as Prime Minister Justin Trudeau tweeted; this is the foundation upon which capitalist states are founded. While recounting the whole story of the assault on Indigenous people in North America is beyond the scope of this article, it’s essential to recognize these attacks have not gone away; they have simply taken new forms.

Indigenous activism has led to crucial and urgent gains. Language revitalization is a grave necessity — many Indigenous languages are fading away, with only a few elders left who are able to fluently speak them. While First Nation language revitalization efforts in Canada have been informally underway since the resistance to language loss in boarding schools, federally recognized and supported language revitalization initiatives, such as the 2019 Indigenous Languages Act, have been implemented only very recently, and even those with significant deficits in federal responsibility.

It cannot be ignored that significant gains have been made in terms of language revitalization and the reclamation of Indigenous education. Yet under capitalism, these are merely concessions that serve to delay the uprisings needed to dismantle it. The ongoing exploitation that continues to marginalize and squeeze out the remaining labor and resources from Indigenous people will not fundamentally change absent organized, strategic resistance from the working class with the goal of tearing down capitalism for good. Capitalism has produced a unique blend of suffocating material conditions for Indigeous folks — rampant poverty, malnutrition, alcoholism, cultural deprivation, and displacement, to name only a few. Yet the conditions faced by other sectors of the working class stem from the same source — the capitalist system, which will always put easy profits over the lives of people.

The 2007 Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement made payouts to over 80,000 survivors of residential schools in Canada. We must demand further compensation for the wrongful deaths of the children who were found in the most recent discoveries. The United States has made no legitimate attempt at reparations for the indigenous people it has assaulted over the country’s nearly 250-year history. On June 22, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland announced that the Department of the Interior would comprehensively review the history of Indian residential schools, with a special focus on their intergenerational impact. In solidarity with indigenous people, we must demand that the U.S. government give reparations which are democratically decided by members of the nations themselves, with the full understanding that reparations will not be enough. We must also demand to put an end to the illegal land encroachment by oil companies and support the resistance of indigenous communities to these disastrous, contaminating invasions, such as the ongoing native-led battle in Minnesota against the Line 3 pipeline.

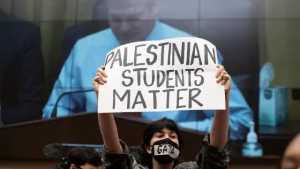

The Indigenous struggle in North America must not be seen in a vacuum — while the specificities of the U.S. and Canadian pogroms should be acknowledged, they must also be recognized as part of a pattern of settler-colonialism that is not in the past. To mourn the unmarked graves of indigenous children while failing to recognize the ongoing murder of indigenous Palestinian children is to be willfully ignorant. Apologies and truth telling is necessary, but it is not enough. The working class needs to stand in solidarity against the assaults on indigenous people all over the world, from Bolivia to Palestine.