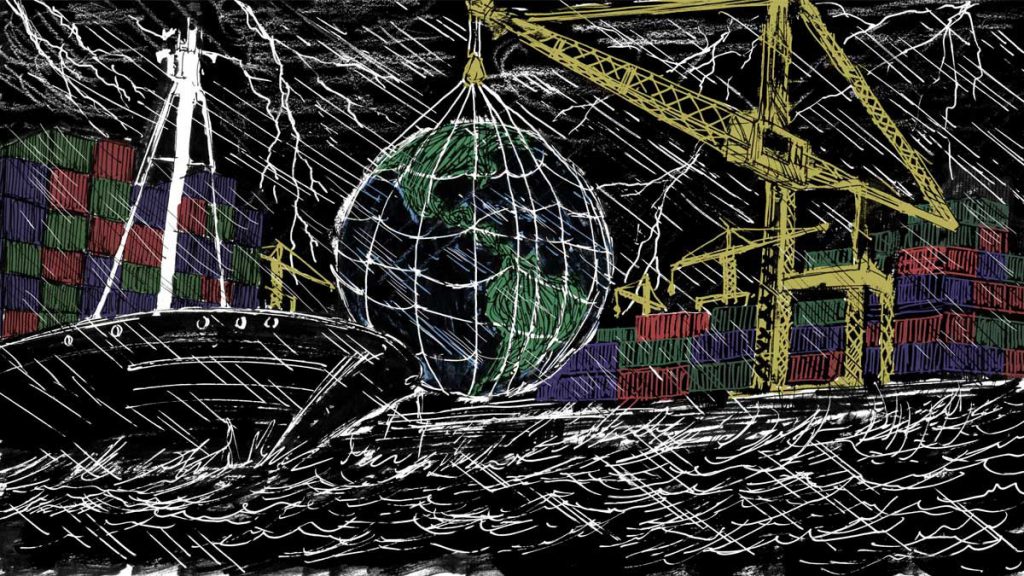

In recent weeks, images of ships stranded near U.S. ports, crowded with unloaded containers, have made headlines around the world. So too have supermarket shelves empty of a wide variety of products. Online purchases that consumers were only recently used to receiving within days (or even hours), with no shipping costs, can now be delayed by weeks.

A Perfect Storm, and Bottlenecks

What we are seeing in the United States is an exacerbated version of what is happening in many other countries that also similarly satisfy a good part of their consumption with import goods produced in other parts of the world through global production chains. These chains have been built up over decades as multinationals have globalized production, seeking to take advantage of low wages, tax exemptions, and lax regulations against pollution in poor and developing countries. Globalized production was based on relocating a good part of the productive processes outside the imperialist countries that, until the 1970s, had enjoyed undisputed industrial primacy, relying on “just-in-time” (JIT) schemes aimed at reducing stocks as a way to reduce costs. But a series of JIT failures has led to the recent problems.

The backup of goods (whether those goods are sitting in containers on ships or stacked in ports) and what has now become a tortuous path through the logistics chains within countries is the result of a steep rise in demand that has come up against overstretched infrastructure — the result of years of underinvestment — and a lack of enough workers to cope with the stresses of distribution. Together, it is a perfect storm.

“Sorry, no french fries with any order. We have no potatoes.” So read a sign recently at a Burger King in Miami. The lack of fries in the land of fast-food chains is a glaring illustration of the extent to which supply chains are being disrupted. There is a shortage of basic foodstuffs. Soft drinks are in short supply (owing to a lack of bottles for packaging, among other reasons), as are corn-based products such as tortillas. So, too, are clothing. Meanwhile, the prices of whatever does reach the supermarket shelves have increased. There are also shortages of medicines and medical equipment, cellphones, computers, cars, washing machines, refrigerators, and microwaves. With Christmas coming, there are shortages of toys, Christmas trees, and plastic cups. Basically, anything that enters the United States through its ports, as well as anything that depends on the country’s extensive internal distribution chains, is in short supply or — in the best cases — has become more expensive because of the costs of getting it to market. This, to a large extent, explains the growing inflation over the last few months.

What’s going on here? Let’s start at the end, where we find a sort of funnel that is causing trouble for the inflow of goods to the United States — a situation replicated in other wealthy countries. First, we have a strong increase in demand. There was already a tendency during the pandemic to channel expenditures that weren’t going to services and activities into purchasing goods, and this grew sharply with the recovery. Container Trades Statistics reports that growth in shipments from Asia to the world’s main economies grew substantially: from January to August 2021, it was 25 percent higher than in 2019, the year before the pandemic — which was a year of economic growth in the United States. That figure is consistent with the robustness of U.S. goods consumption, which Capital Economics reports was 22 percent higher in August 2021 than in February 2020, when Covid-19 seemed to be a problem only for China and purchases in the United States were chugging along as usual.

While it might seem that this higher volume of merchandise should be manageable without problems, that has not been the case. After years of disinvestment in port infrastructure — all part of the logic of operating at a level just enough to maximize profits — the extra margin of capacity in major U.S. ports was estimated to be no more than 5 percent, according to Gary Hufbauer of the Peterson Institute for International Economics. A fivefold increase in that margin could predictably lead to a bottleneck that quickly turns into chaos. Everything that would typically go smoothly becomes a disruption: containers that are usually emptied quickly and returned to the ships instead pile up at the port because there aren’t enough workers or trucks; newly arriving container ships are delayed just outside the port or are diverted to other ports, which are often less able to handle them, where the same congestion tends to be reproduced.

Beyond the infrastructure problems, there is the shortage of port staff and truckers. While this is partly a result of the pandemic, it also flows from a more far-reaching problem: the degradation of working conditions in the industry, which are far worse than they were decades ago. As Rebecca Heilweil argues in Vox/Recode, “Worsening conditions for truck drivers in the U.S. have made the job incredibly unpopular in recent years, even though the demand for drivers has gone up as e-commerce has become more popular.” The fact that Amazon — not exactly known for the good working conditions of its delivery drivers — is poaching drivers from trucking companies should be enough to give an idea of the actual state of the industry. As Matt Stoller observes,

Driving a truck, which used to be a middle-class job in the 1970s, has become a cyclical low-paid profession with high burnout and little stability, a so-called “sweatshop on wheels.” While it’s tempting to blame this situation on trucking firms, the reality is that the problem is due to the market structure of transportation created by the deregulation of the 1970s.

As the pandemic raged, many veteran truck drivers took early retirement, and new drivers couldn’t obtain their licenses because trucking schools were closed during the shutdown. This meant, as Heilweil writes, that “as Americans relied more on online shopping during the pandemic, getting goods from ports to doorsteps has been challenging.” And while the Biden administration has secured a commitment from logistics companies to work around the clock to relieve freight congestion, staffing shortages may conspire against these efforts.

Bottlenecks at the entry points of goods is just one of the disruptions that global supply chains face. After the production stoppages during the worst of the pandemic — although it must be noted that employers made every effort to frame their businesses as essential regardless of the risks to the workforce — many companies saw their stocks reduced below normal levels, making it difficult to cope with sharp increases in demand. Rebuilding stock levels takes time. It requires putting the production apparatus at full throttle to produce at faster-than-normal rates, but it also depends on having raw materials and components that are not always available. Stock shortages extend all along the production lines. Add to this that transit times between countries haven’t returned to normal; they’ve gotten longer. This affects not only getting products to their final destinations, but also moving components to assembly sites.

On top of that are other problems that predate the pandemic, such as the one plaguing semiconductor production. As Chad P. Bown observes in Foreign Affairs, one of the biggest culprits in the semiconductor shortage “was a sudden shift in U.S. trade policy.” The Trump administration in 2018 “launched a trade and tech war with China that jolted the entire globalized semiconductor supply chain. The fiasco contributed to the current shortages, hurting American businesses and workers.”

In May, lead times for chip orders stretched to 18 weeks — four weeks longer than the previous peak. This affects all sorts of sectors: computers, phones, automotive, appliances, and even aircraft production, which has also been hampered by the lack of this critical component.

What’s happening in China hammers home that things are far from returning to normal. The world’s main industrial producer and exporter is experiencing an energy crisis that has forced it to impose recurring shutdowns in its manufacturing sector. This means further tightening that will continue to strain a supply chain already under maximum stress.

The Benefits and Contradictions of Global Value Chains

Over the last few decades, multinational companies have perfected internationalized structures of production that have been dubbed “global value chains.” They were configured as part of a sweeping restructuring of goods production (and, increasingly, services as well). Two processes went hand in hand. First, production lines were gradually broken down into a series of partial production stages, in which different independent production units each take charge of a single stage or specialize in producing some set of components. Second, many of these operations were relocated from the wealthier, increasingly deindustrialized countries to a number of dependent countries, mostly in Southeast Asia. This was especially the case with “labor-intensive” operations. As a result, “assembly lines” came to span tens of thousands of kilometers or more across dozens of countries.

The creation of global value chains was made technically possible by improvements in communications technology and reductions in transportation costs (a milestone was achieved with the implementation of containers and, since then, many “revolutions” have lowered freight costs even more). The main driver was finding a way to take advantage of the cheap labor force in the poor and middle-income countries — in ways never before possible — which had undergone growth in their industrial production. In the late 20th century, the world’s manufacturing sector shifted to China and, more broadly, to a host of dependent countries that together saw their industrial workforce grow from 322 million to 361 million, while the manufacturing workforce in the developed countries fell from 107 million to 78 million (still a significant number that belies any idea of that the industrial workforce in these countries has disappeared).1United Nations International Development Organization (UNIDO), Industrial Development Report 2018. Demand for Manufacturing: Driving Inclusive and Sustainable Industrial Development (Vienna: UNIDO, 2017, 158). The industrialization that took place in this periphery that benefited from the relocation of production was, in most cases, deformed by specialization in only partial production processes, always under the control of the multinationals. This led to quite limited transformations in the productive structures of these countries compared to industrialization in the developed countries, or even in dependent countries, during most of the 20th century. In the overwhelming majority of cases, the aspiration to climb the development ladder by becoming part of these value chains proved elusive.

Global value chains became the latest craze for production efficiency, based on the idea (according to the terms of mainstream economics) that operations that rely most heavily on the labor-intensity “factor” — that is, the simplest, most repetitive tasks — could be located in the countries that offer the greatest abundance of this “factor.” The most reputable consultants and analysts urged the industrial and service firms of the imperialist countries, large and small, to take part in this great offshoring and globalization of production in the name of economic “rationality” — lest they face intense competition from those more adept at doing so, even at the risk of perishing altogether. As these global chains strengthened and new technologies made it possible to provide digital services at a distance, this craze expanded to more and more intangible production. No longer was it only the simplest and most repetitive tasks that were subjected to this international competition that capital imposed on world’s labor forces.

From the point of view of multinational capital, the rationale for global value chains was based on the fact that countries competed to offer more “flexible” (that is, precarious) working conditions, tax at lower rates, and accept polluting practices that imperialist countries no longer tolerated. Thus, it seemed completely reasonable, because it was profitable for firms to break down their production processes by having certain units perform specialized tasks — an ideal way to increase productivity and lower costs.

Doing so, however, meant far greater demands on logistics. It is not only that finished products must travel enormous distances to reach consumer markets; components must also travel long distances to reach final assembly sites. When fuel is cheap, this is a polluting waste, one that has no social efficiency or rationality. In fact, it’s quite the opposite. The value chains’ “externalities” worsened the environmental consequences of globalized production. “Externality” is another term from mainstream economics that arbitrarily converts the consequences of firms’ actions on the environment into something “external.”

Under different circumstances, globalized production could be the path to a better system of production that meets the entire world’s social needs — focusing on the reduction of working time and achieving a harmonious relationship between society and nature, rather than today’s alienated relationship, which is taken to its absurd limits by multinationals that seek only to maximize their profits. These very business leaders who, at the Davos forums, feign contrition when they talk about climate change and insist that corporations must combat it, are the main protagonists of this version of globalization, which makes sense only for the capitalists. But even for them, it only makes sense under certain conditions. Sometimes, it can be an economic catastrophe — as today, with fuel costs skyrocketing and the cost of container freight growing by leaps and bounds (according to Statista, it grew eightfold from July 2019 to September 2021).

Global chains, with all the advantages they provide in normal times for transnational firms to deliver cheap goods to your doorstep at low cost, can turn into a nightmare when unexpected events occur, as with the border closures and the quarantines of 2020. That is why the concept of “resilience” became so prevalent last year as a new element to incorporate into the value chains equation. Given the evidence of just how precarious this globalized production scheme really was, since it threatened to leave many countries and regions without basic goods, the consultants concluded that too much dependence on a few firms or supplier countries could increase the risks, so it is necessary to diversify. It is their way of mincing words, given how bewildered and nervous they are now that it seems less and less promising, across the world, that the cost differences that were so profitable for so many decades are still available. Before the pandemic, the rising specter of protectionism and glimpses of trade wars put a question mark on continuing globalized production, which had already begun in 2015 or even earlier to show many signs of weakness (trade and foreign investment grew at a slower pace than the overall world economy). But after the upheavals of the pandemic and the current situation, questions about the future are proliferating.

All that remains to be seen. What is certain is that the disruptions — despite all the efforts to quicken the pace of logistics and to unclog the ports — will continue for several more months, because the consequences of the problems that exist all along the global production chain will continue to appear.

Bottlenecks as a Strategic Dimension

The shock to supply chains from so many bottlenecks has brought to the forefront something that some sectors of the working class in the logistics sectors had already experienced and took advantage of firsthand. A capitalism organized through value chains — allowing companies to profit from pitting workforces across the globe against each other and imposing degraded working conditions and wages worldwide — exposes itself to all manner of fragilities that are intrinsic to the configuration of these transnationalized assembly lines. This is now becoming apparent. But it is not just these failure points, resulting from objective contingencies, that create the disruptions we are seeing today. It has also become clear that sectors of the workforce can take action on fundamental links in the production chains — links that capital needs to function with clockwork precision. From a strategic perspective in the struggle against capital, these choke points are pivotal.

As Kim Moody observed in his 2017 book On New Terrain, “More and more aspects of production are tied together in just-in-time supply chains that have reproduced the vulnerability that capital sought to escape through lean production methods and relocation.”2Kim Moody, On New Terrain: How Capital Is Reshaping the Battleground of Class War (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2017), 115.

Consider the case of the United States. By developing supply chains aimed at accelerating how quickly goods can be moved, capital has created a formidable workforce in this sector. Today, it employs 9 million people, or 6.3 percent of the country’s workforce. And far from being diffused and thus presenting a challenge for organizing, many are concentrated in large-scale warehouses that employ hundreds of people.

In a more recent interview, Moody returns to this question. He notes that the concentration of resources and workforces in logistics, aimed at making the transit of goods happen as quickly and smoothly as possible, has created gigantic clusters. In Chicago alone, he calculates, it comprises an army of 200,000 people.

What they’ve done is recreate what business in the U.S. tried to destroy thirty years ago when they moved out of cities like Detroit or Gary or Pittsburgh. They tried to get away from these huge clusters of blue-collar workers, particularly unionized ones and workers of color. Now, in order to move goods — across much more spread out production chains than in the past — they have recreated these huge concentrations of low-paid workers.

These clusters are choke points in a very real sense. If you stop a small percentage of activity going on in these places, you back up the whole movement of goods and the economy.

In the same vein, Jake Alimahomed-Wilson and Immanuel Ness state in the foreword to Choke Points: Logistics Workers Disrupting the Global Supply Chain:

Logistics workers are uniquely positioned in the global capitalist system. Their places of work are also in the world’s choke points — critical nodes in the global capitalist supply chain — which, if organized by workers and labor, provide a key challenge to capitalism’s reliance on the “smooth circulation” of capital. In other words, logistics remains a crucial site for increasing working-class power today.3Jake Alimahomed-Wilson and Immanuel Ness, “Foreword,” in Choke Points: Logistics Workers Disrupting the Global Supply Chain, ed. Alimahomed-Wilson and Ness (London: Pluto Press, 2018), 2.

The bosses are well aware of how dangerous it is to bring together thousands of workers in these clusters. That is why they have such an aggressive anti-union policy, using blackmail and threats in an effort to prevent the workers from organizing — with the collaboration of sectors of the union bureaucracy itself. Such is the case with Amazon, which fiercely faces down any attempt to organize its warehouses or its fleets of truck drivers, following the example of Walmart and McDonald’s, the other two main employers (which Amazon is on the way to dethroning).

Today, the logistics workforce is, thanks to just-in-time production chains, more intertwined than ever with the sectors that produce goods (which in the United States, despite the all the talk about “deindustrialization,” is still a workforce of no fewer than 12 million people, or 8.5 percent of the country’s total) and also with workers who provide various services. This flies in the face of the idea of the “end of work” or that the working class has lost its relevance. Rather, the centrality that the global chains give the working class in the production and distribution of basic goods and in the provision of fundamental services could not be greater — and that doesn’t even account for the work of reproducing the labor force, which takes place outside the market and is made invisible by the political economy of capital. The working class is the social force capable of activating the emergency brake on the irrationality of capital that, in the global chains of production, is once again giving us new examples of its multiple crises.

The strategic positions occupied by the logistics workforce, as well as those sectors engaged in the production of goods and the provision of services in these increasingly integrated supply chains, give them power at the center of the confrontation against capital; they can paralyze the normal circulation of goods and valorization. These strategic positions are also a fundamental foothold — moving past the trade union bureaucracies that maintain the division of the working class — for creating an independent force that can unite the exploited and oppressed, starting at production units and other nerve centers (company, factory, school, hospital, logistics center, transport system and stations, etc.), with its own methods of self-organization and with a view to confronting capital and the perspective of reorganizing society on a new basis.

As for the choke points that have been exposed by the supply chain, it is essential that we determine what they mean for the class struggle, especially at this moment when the working class in the United States is on the move — as we see from the strikes in so many enterprises and an unfolding anti-bureaucratic process.

First published in Spanish on October 24 in Ideas de Izquierda.

Translation by Scott Cooper

Notes

| ↑1 | United Nations International Development Organization (UNIDO), Industrial Development Report 2018. Demand for Manufacturing: Driving Inclusive and Sustainable Industrial Development (Vienna: UNIDO, 2017, 158). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Kim Moody, On New Terrain: How Capital Is Reshaping the Battleground of Class War (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2017), 115. |

| ↑3 | Jake Alimahomed-Wilson and Immanuel Ness, “Foreword,” in Choke Points: Logistics Workers Disrupting the Global Supply Chain, ed. Alimahomed-Wilson and Ness (London: Pluto Press, 2018), 2. |