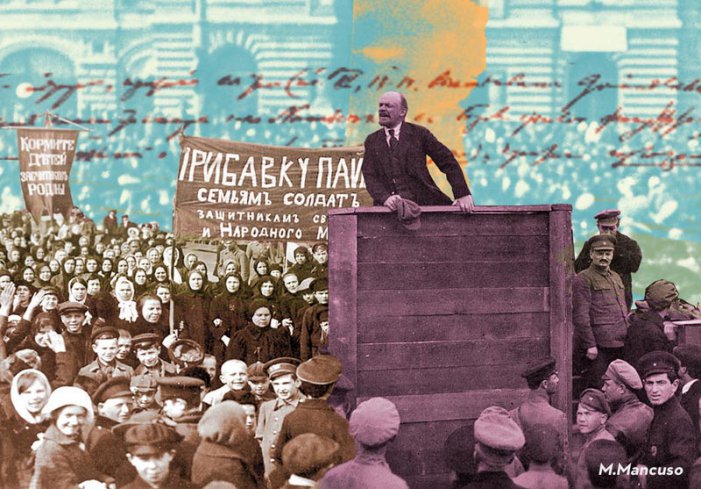

The workers in Russia created the first dictatorship of the proletariat, contrary to social democratic claims that socialism would first arise out of the highly industrialized nations. Profound reforms were won through armed revolution in the most under-developed nation in Europe, pushing Russia into the vanguard of world history. But the country’s economic and cultural backwardness, combined with the defeats of the workers’ movement in the advanced countries, obstructed the path between the initial moment of the revolution and the final goal of socialism.

From 1918 to 1921, when the brand-new workers’ state went through the period known as “war communism,” efforts were concentrated on the development of military industries and the fight against the hunger that ravaged cities. Across Russia, industry produced less than one-fifth of what it had produced before the imperialist First World War. Moscow’s population was half the pre-war level, Petrograd’s barely a third. Meanwhile, revolution was defeated in one of the most advanced capitalist countries in Europe: Germany. As a result, the conservative forces of Europe’s ancien régime were able to regain their footing. By the beginning of 1919, the reactionary European project of surrounding the nascent Soviet republic had been consummated.

The hope that the Bolshevik leadership placed in the German revolution was no mere daydream of a group of out-of-touch leaders; the survival of the Soviet power during its first few months was due to the European proletariat; among them, the heroic German working class stood out — these workers had toppled the Reich In the midst of the imperialist war. The fate of the Russian Revolution was, in the eyes of Lenin and Trotsky, inextricably tied to the resolution of this monumental battle of one class against another in one of the most developed capitalist countries of that time.

As the survival of Soviet Russia hung in the balance, the first workers’ state in history passed an unprecedented legislative measure. “The Soviet regime was hardly one month old when it issued a decree that the Provisional Government had proved incapable of issuing throughout its eight months’ existence: The law introducing the right to divorce, and, in particular, to divorce by mutual consent. (About the same time, civil marriage replaced religious marriage.)” (1)

The historian Henri Chambre points out that Soviet legislation was based on two fundamental principles: “the emancipation of women and ending the policy of unequal rights between legitimate and illegitimate children” (2). Wendy Goldman shares this assessment: “From a comparative perspective, the 1918 Code was remarkably ahead of its time. Similar legislation concerning gender equality, divorce, legitimacy and property has yet to be enacted in America and many European countries. Yet despite the Code’s radical innovations, jurists were quick to point out ‘that this is not socialist legislation, but legislation of the transitional time.’ As such the Code preserved marriage registration, alimony, child support, and other provisions related to the continued if temporary need for the family unit. As Marxists, the jurists were in the odd position of creating legislation that they believed would soon become irrelevant”(3).

II

The 1917 revolution, World War I, the post-revolution civil war, droughts, and plagues had turned old Russia on its head. By the end of 1920, disease, hunger and freezing temperatures had killed 7.5 million Russians, while the war had claimed 4 million more lives.

Thousands of children roamed the streets, searching for bread crusts to keep them alive. They were the orphans of war, revolution, and famine and had needs that the young workers’ state struggled to address. The “besprizornost” (street children) were accustomed to theft, vagrancy, hard lives, and rough treatment from authorities, and when the agricultural economy was incentivized, they were sent into the fields. “In 1926, 19,000 homeless children were removed from state-funded children’s homes and placed in extended peasant households to sow with a centuries-old wooden plough, and to reap with a sickle and scythe,” Goldman describes (4). In 1925, educator T.E. Segalov used Fourier’s famous comment about women and applied it to children. He writes, “The manner in which a given society protects childhood reflects its existing economic and cultural level.” In some respects, this did not bode well for the USSR.

At the same time, there were also tremendous innovations in the study of child development and an unprecedented pedagogical revolution. Everyone who knew how to read and write was mobilized for a massive literacy campaign; literary classics were published, co-educational schooling was established, and education was given a polytechnic and collective character. Exams were abolished and schools were managed by a council of the school’s workers, representatives of local workers’ organizations and students over the age of twelve. The new Soviet republic made all university education free.

Revolutions, no matter what their ideals and intentions, have to work with the existing material conditions to radically transform society. This includes making difficult decisions within a context of heartbreaking contradictions, as was evident in the USSR. Amidst these violent contradictions, the revolution struggled to survive and find its way. Cheap books, meant to help the literacy campaign, often ended up in the fire, keeping their intended readers from freezing as a result of the shortage of fuel.

These were the contradictions of the post-revolution USSR.

Part II of this article will be most in the next few days.