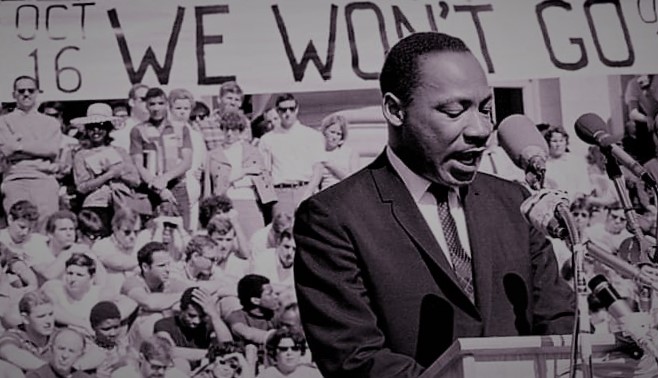

When most people think of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s writing, they think of his famous “I Have a Dream” speech or perhaps his “Letter From a Birmingham Jail.” King is uncontroversially one of the great leaders of the civil rights movement, but the more radical aspects of his politics are generally unknown. For example, his stance on the Vietnam War, one of the bloodiest conflagrations led by U.S. imperialism in the 20th century.

Read or listen to King’s “Beyond Vietnam” speech in full here.

King delivered “Beyond Vietnam — Time to Break Silence” on April 4, 1967 at the Riverside Church in Morningside Heights in Manhattan, a nondenominational and highly diverse church with a long history of social justice initiatives. In this speech, King speaks out against U.S. imperialism and discusses how war is always conducted at the expense of the international working class and always benefits the ideological and material interests of the dominating country, not the people they are supposedly “helping” through their intervention. While King was of course speaking about the ongoing Vietnam War, much of the speech can be directly applied to current U.S. military actions in the Middle East, including the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the conflict in Syria, and the developing situation in Iran.

King opens the speech by quoting a statement from the Clergy and Laymen Concerned about Vietnam, that “A time comes when silence is betrayal.” He says it is long past time for him to break his silence on the war and speak from “the burnings of my own heart,” and urges others to do the same.

In the first main section of the speech, King lists several reasons he is morally and politically opposed to the war, and sees the anti-war movement as fundamentally intersecting with the struggle for civil rights, which we can apply to today’s situation as well:

The U.S. government uses war as an excuse to divert funding from domestic social programs.

In his case, King was referring to the poverty program, which he thought would have significant positive outcomes for the working class of all races. However, as tensions in Vietnam began to build, the program was “broken and eviscerated, as if it were some idle political plaything of a society gone mad on war.” King described war as a “demonic destructive suction tube” funnelling people and resources toward violence.

Debating the amount of money that ought to be spent on war vs. social programs is ultimately reformist, but it remains true that the U.S. routinely uses war as a way to control the working class. A more recent example is the PATRIOT Act, which significantly increased digital surveillance and invasions of privacy on U.S. citizens and people around the world in the name of anti-terrorism. Even more recently, we can look at Trump’s attempted travel ban against Muslims entering the U.S. and the Iranians detained at airports just in the last two weeks.

King perhaps begins with this argument because it is the most politically palatable. We see many liberals today making similar arguments — that social programs like Medicare for All and tuition-free universities would be possible if only the U.S. government would divert money from military spending. This argument also implies that the primary problem with military spending is that it takes away money from solving domestic problems, not that the U.S. military is a weapon of imperialist violence around the world. Rather than criticizing the U.S.’s desire to violently interfere with another country’s democratic revolution against colonial powers (France and Japan), he first prioritizes U.S. interests before developing more radical arguments.

War uses the working class as cannon fodder

The U.S. military is disproportionately made up of Black people, working class people, and people without a college education, and the same was true during the Vietnam War. King notes the hypocrisy of allowing white and Black soldiers to fight and die together while not allowing them to eat, live, or learn together at home.

The statistics are even worse when looking at those conscripted via the draft: about 11-14% of Vietnam veterans were Black, but about 16% of draftees were Black. Additionally, Black Vietnam soldiers found themselves disproportionately court-martialed, assigned to combat roles, placed in military prisons, and assigned nonjudicial punishments. While the racial breakdowns for combat deaths over the course of the entire war are close to proportional with enlistment, in 1965, about 25% of U.S. military members who had died in Vietnam were Black.

The deaths of the Vietnamese during the imperialist intervention were even more numerous. The Encyclopedia Britannica estimates that about 2 million Vietnamese civilians (from both the North and the South) died during the war, about 1.1 million soldiers from North Vietnam and Vietcong members, and between 200,000 and 250,000 soldiers from South Vietnam. In Vietnamese civilian deaths alone, that’s about the entire current population of New Mexico (the 36th most populous state). When including both civilian and military deaths across all involved countries, it amounts to around the total current population of Connecticut (3.5 million, the 29th most populous state). Each of those deaths is a victim of imperialist violence.

The U.S. government should not get a moral exception.

King says that over the past few years, as he tried to promote his tactic of nonviolence among Black youth around the country, many people asked him, “What about Vietnam?” Between the military and the police force, state violence is the ultimate expression of the belief that violence gets results. In his own words, “I knew that I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today — my own government.”

While state violence can take many forms, including war and police brutality, the U.S incarceration rate per capita alone outpaces the nationwide rate of violent crime per capita. If we are to be concerned about interpersonal violence in the name of safety for U.S. citizens, we must first be concerned about state violence and the class warfare it represents and maintains.

Moral duty extends beyond any racial or national boundary.

As a Christian minister, King viewed his ultimate calling as one of “sonship and brotherhood” to all people. However, while he thinks of his obligation in Christian terms for himself, he does not limit his internationalism to one faith, but to anyone who finds commonality across national boundaries:

This [care for all suffering people] I believe to be the privilege and the burden of all of us who deem ourselves bound by allegiances and loyalties which are broader and deeper than nationalism and which go beyond our nation’s self-defined goals and positions. We are called to speak for the weak, for the voiceless, for the victims of our nation and for those it calls “enemy,” for no document from human hands can make these humans any less our brothers.

As Trotskyists, we are unconditionally against imperialism and support militant resistance to it around the world. We believe that the common enemy of the working class and the oppressed is global imperialism and the capitalists who exploit us within national borders. The working class has no homeland — our allies are the exploited and oppressed of the world. Although MLK’s internationalist sentiment was correct, it lacks a class analysis of the world order and U.S. imperialism, which prevented him from developing a more thoroughgoing anti-Vietnam War policy that would call for the unification of the U.S. working class, the Black liberation movement, and the Vietnamese working class against the same enemy.

King demonstrates this analysis himself as he ponders the history of U.S. involvement in Vietnam. “They [the people of Vietnam] must see Americans as strange liberators,” he says, observing that Vietnam had already declared its independence from France in 1945, quoting the U.S. Declaration of Independence in its founding documents, yet the U.S. refused to acknowledge their sovereignty.

In King’s own words:

They watch as we poison their water, as we kill a million acres of their crops. They must weep as the bulldozers roar through their areas preparing to destroy the precious trees. They wander into the hospitals with at least twenty casualties from American firepower for one Vietcong-inflicted injury. So far we may have killed a million of them, mostly children. They wander into the towns and see thousands of the children, homeless, without clothes, running in packs on the streets like animals. They see the children degraded by our soldiers as they beg for food…What do the peasants think as we ally ourselves with the landlords and as we refuse to put any action into our many words concerning land reform? What do they think as we test out our latest weapons on them, just as the Germans tested out new medicine and new tortures in the concentration camps of Europe?

King continues by expressing empathy for the hatred and distrust the National Liberation Front must feel toward the United States and recognizing that they are the only organized political party in the country actually in touch with the needs of the peasants: “Surely we must understand their feelings, even if we do not condone their actions…Surely we must see that our own computerized plans of destruction simply dwarf their greatest acts.”

Regrettably, most of the rest of the speech is spent advocating in favor of a “peaceful revolution of values” led by the United States in order to avoid true socialist revolution around the world. However, while we may disagree with Dr. King that meaningful revolution is possible through social reforms, he is right that such horrible wars will continue “unless there is a significant and profound change in American life and policy.”

In the last months of his life, Dr. MLK shifted to the left and correctly identified the link between the civil rights struggle and the fight against the Vietnam War. He clearly identified that the enemy of both the Vietnamese people and the Black people in America was the U.S. government. And it was for that reason that he was assassinated. Today we salute his legacy and remember him with an eye toward our own domestic and international situation, learning from his mistakes and successes for the struggles to come.