Over the past few months, a debate has unfolded among Marxists concerning the legacy of Karl Kautsky, the onetime “Pope of Marxism” and leading theorist of the Second International (1889-1914).

It is surely no coincidence that this is happening now. As more and more self-identified socialists win elected office in the United States, the chance of building working-class power through elections seems, to many on the left, greater than it has in decades.

In this context, it is easy enough to understand the lure of Kautsky’s vision of the “road to power”—in which the call for overthrowing the bourgeois state, though perhaps acknowledged in principle, is in effect deferred indefinitely in favor of building political power within that state.

Equally understandable is the desire of all sides, pro or con, to find support for their views in the writings of the great revolutionary socialists of the time, Lenin in particular.

Of course, we can never assume that Lenin (or anyone else) can give us the last word on this or any other subject. The point is not to argue from authority, but rather to try to understand how the greatest minds of the Marxist tradition grappled with these ideas in real time, as the events that shaped them were actually unfolding.

“Architect of the Russian Revolution”?

The most recent contribution to this discussion comes from Lars Lih, author of the magisterial and exhaustive “Lenin Rediscovered: ‘What Is to be Done?’ in Context” (2005).

In an article posted on the Jacobin website on June 29, Lih argues that Kautsky should be viewed not only as “mentor to the Bolsheviks […] on the issues that defined them and divided them from their Menshevik rivals,” but even as “the architect of the Russian Revolution.”

Lih begins backing away from this last extraordinary claim with his very next sentence.

Of course, I am not saying that Kautsky was necessarily the first to come up with these ideas or that the Bolsheviks did not arrive at them independently. But Kautsky gave authoritative endorsement to the key tactical ideas of Bolshevism, giving clarity and confidence to the Russians with an impact that is hard to overestimate.

So we have here an “architect” who, so to speak, neither came up with the design concept nor drew up the actual plans used in construction, but merely provided his “authoritative endorsement.” Not exactly a compelling case.

But if Lih’s claims for Kautsky as “architect” are easily dismissed, closer attention should be given to his arguments concerning the continued importance of Kautsky’s writings to the Bolsheviks, and to Lenin in particular, even after Kautsky had, in their view, turned “renegade” around the outbreak of the First World War.

Lenin’s “Kautsky Fixation”

“[D]id Lenin actually ever reject Kautskyism, if by this term we mean the ideas that he, Lenin, had earlier praised so enthusiastically?” Lih writes. “What, in fact, did the post-1914 Lenin have to say about the pre-1914 Kautsky?”

Luckily [Lih continues], Soviet scholars created a research tool that allowed me to answer this question definitively: Exhaustive bibliographic references to any literary production mentioned by Lenin in any way. …

What I found stunned me. First of all was the sheer volume of references—not just to the post-1914 Kautsky who became a more and more virulent critic of Bolshevism—but rather to long-ago Kautsky publications from before the war. Lenin’s remarks start immediately after the outbreak of war in 1914 and continue right up to the end (Lenin’s last article contains one). Clearly Lenin had a Kautsky fixation, even while Kautsky was becoming yesterday’s man in the West.

The references are also remarkable for the wide range of Kautsky’s pre-1914 writings that Lenin felt called upon to discuss. Indeed, Lenin once answered a party questionnaire by affirming that he had read just about everything by Kautsky. And finally, these references are striking because they are overwhelmingly positive. Taken all in all, they constitute a strong endorsement of Kautsky-when-he-was-a-Marxist (as Lenin expressed it).

Lih acknowledges that Lenin attacked Kautsky “relentlessly” after 1914, but argues that he did so “[p]recisely because he saw Kautsky as a renegade, that is, as someone who renounced or refused to act on his own correct views.” At no point, Lih argues, did Lenin seriously waver in his admiration for the ideas Kautsky had advanced before turning renegade.

Lih has been over all this ground before, notably in a talk given at the Left Forum in New York City in March 2008. Regrettably, the passage of 11 years seems to have done little to lessen the current of mystification that, deliberately or otherwise, runs through Lih’s account.

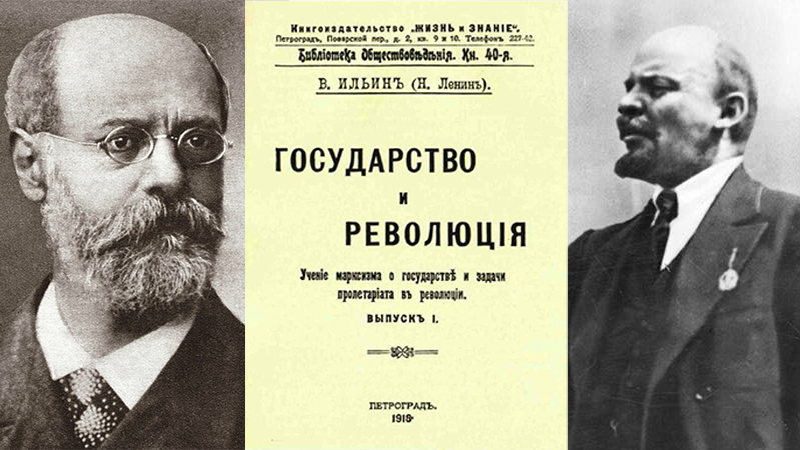

To begin with, as Lih knows perfectly well, one needn’t go hunting through neglected Soviet bibliographies to discover “what the post-1914 Lenin had to say about the pre-1914 Kautsky.” Indeed, “State and Revolution,” arguably the most famous of all Lenin’s works, devotes a good deal of space to this very point (as we shall see later on).

Yet Lih professes to have been “stunned” by the results of his research. What can this mean? Surely such a response makes sense only if the crop of unfamiliar references he has gathered reveals new and surprising insights.

The implication seems to be this: If we base our understanding of Lenin’s views primarily on his “greatest hits” (“State and Revolution,” “Left-wing Communism,” “Imperialism” et al.), we will come away with a picture that is distorted, if not simply wrong. To know what Lenin really thought about Kautsky, Lih seems to be saying, we must follow the path that Lih himself has taken.

Naturally, as with any writer, the more of Lenin we read, the better we will understand his ideas and how they developed over time. But the question here is not whether Lih’s discoveries deepen our understanding of Lenin’s views on Kautsky—undoubtedly they do—but whether they fundamentally alter that understanding.

Lih offers no evidence that this is so. What he offers instead is, despite the depth of his research, not a more detailed picture of Lenin’s relationship with Kautsky’s writings but a much cruder one.

Back When Kautsky Was a Marxist

For Lih, it seems, Lenin’s postwar view of Kautsky can largely be reduced to a single two-part formula: (1) Lenin quotes approvingly from something Kautsky wrote before 1914; (2) Lenin adds an acerbic remark concerning how well Kautsky thought and/or wrote before he turned renegade.

It is certainly very easy to find examples that fit this pattern. Take, for instance, the opening chapter of “‘Left-Wing’ Communism: An Infantile Disorder” (1920), in which Lenin quotes a lengthy except from an article by Kautsky that had appeared in the underground Russian socialist newspaper Iskra in 1902.

Lenin begins by framing the source article as a product of “bygone days, when he [Kautsky] was still a Marxist and not a renegade,” and then, after the quotation, closes his chapter by observing, “How well Karl Kautsky wrote eighteen years ago!”

Lih’s formula obviously has merit when applied to passages such as this. But it is hardly news that such passages exist: As we have just seen, they can be found in some of Lenin’s best-known works. Perhaps the number of similar passages uncovered by Lih may be unexpected, but he offers no hint of anything in their content that ought to surprise us.

This is perhaps why Lih emphasizes the “sheer volume” of “overwhelmingly positive” references to Kautsky that he found in Lenin’s post-1914 writings.

It would be one thing, he seems to be saying, if Lenin made only an occasional and grudging reference to something Kautsky had written before turning “renegade.” But since Lenin constantly quotes Kautsky approvingly, surely that must mean that he never abandoned his prewar enthusiasm for the latter’s “pre-renegade” works?

We might begin to answer this question by challenging Lih’s characterization of Lenin’s approving references to Kautsky as “overwhelmingly positive.” Consider again the passage from chapter 1 of “Left-Wing Communism,” described above: Taken as a whole, with the quotation framed by Lenin’s bitter commentary, does this passage strike you as “overwhelmingly positive”?

More importantly, the effect of this line of thinking is to reduce Lenin’s views on the writings of Kautsky to a simple question of fandom. The idea seems to be that, by simply counting up the numbers of positive and negative references to Kautsky in Lenin’s work, we can produce a final, thumbs-up or thumbs-down verdict: Either Lenin was a fan of Kautsky, or he was not.

Such judgments are as useless as they are facile. If someone argues that Lenin disagreed with Kautsky on a particular issue, it is no response at all to say, “Actually, Lenin was a big fan of Kautsky. He was always quoting approvingly from his works.”

The Small Matter of “State and Revolution”

But easily the most serious problem with Lih’s thesis is that, by characterizing Lenin’s attitude toward Kautsky as essentially a long series of “overwhelmingly positive” endorsements, he all but ignores the fundamental criticisms of the pre-1914 Kautsky that the post-1914 Lenin undeniably did make, most notably in “State and Revolution.”

In his 2008 Left Forum talk (though, curiously, not in the current Jacobin article), Lih did acknowledge that one of the objections likely to be raised against him was the fact that “in State and Revolution … Lenin specifically criticizes some prewar writings by Kautsky that he, Lenin, had previously admired greatly.”

In fact, as we shall see, Lenin does far more in “State and Revolution” than merely “criticize some prewar writings by Kautsky.”

In any case, having thus minimized the objection, Lih makes a rather feeble attempt to brush it aside:

The discussion of Kautsky in “State and Revolution” also contains many strong statements that show Lenin’s continued appreciation of the very writings he criticizes. In any event, the writing of “State and Revolution” in 1917 causes no appreciable blip in the flow of positive references to Kautsky’s prewar writings.

Here again we encounter the notion of fandom: Sure, Lenin may have expressed some disagreements with Kautsky in this book, but overall, he was still a fan, so the criticisms can’t have been too bad.

Actually the criticisms raised in “State and Revolution” matter very much—all the more so today, when so many people seem eager to rehabilitate Kautsky while minimizing or even ignoring the profound flaws in his thinking.

Opportunism and the Question of State Power

For Lenin, the besetting vice of the Second International was opportunism—that is, the betrayal of the interests of the international working class in order to benefit some smaller group, such as one’s own labor bureaucracy.

Writing in 1915, Lenin described the economic basis of opportunism as “an alliance between an insignificant section [insignificant in size, that is] at the ‘top’ of the labour movement, and its ‘own’ national bourgeoisie, directed against the masses of the proletariat.”

Lenin’s aim in “State and Revolution” was to counteract the distortions and evasions that had come to obscure Marx and Engels’ “theory of the state” as a result of two decades of ever-increasing opportunism. In the preface to the book, he names the individual whom he regards as “chiefly responsible for these distortions”: Karl Kautsky.

Of particular importance to the development of Lenin’s argument was the great lesson that Marx and Engels had drawn from the experience of the Paris Commune in 1871: Namely, as Marx phrased it in “The Civil War in France” (1871), that “the working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made state machinery and wield it for its own purposes.” Instead, Marx and Engels argued, the proletariat must smash that machinery and replace it with something new.

This is because the institutions of the capitalist state are institutions of class rule. This is not simply a consequence of mismanagement or corruption; rather, it is a fundamental property of the institutions themselves.

Consider, for instance, the police force in any city: While it certainly makes some degree of difference how conservative or “progressive” the chief of police happens to be at any given time, the force as a whole remains at root an instrument of oppression, structured to “protect and serve” the ruling class while keeping the lower orders in line. This is basic to its very nature. Such an institution cannot simply be “reformed” and taken over: It must be smashed.

As Lenin argues forcefully in “State and Revolution,” the conclusion that the bourgeois state cannot simply be taken over by the working class, but must instead be smashed, was a vital development in Marx and Engels’ conception of the dictatorship of the proletariat—the period between the initial victory of the working class over the bourgeoisie and the ultimate withering away of the state. But thanks to opportunism, this conclusion fell increasingly on deaf ears during the period of the Second International.

It’s not hard to see why this was so. This was a time when working-class political parties, above all the German Social Democratic Party (SPD), were growing ever larger and becoming steadily more successful (occasional drawbacks aside) in winning parliamentary seats. The temptation to make some sort of peace with the capitalist system, rather than seek to overthrow it, must have been very strong.

The reality that any such “peace” could, at most, benefit a small layer of the working class while consigning everyone else to continuing oppression and exploitation, seems not to have overly troubled those who succumbed to the lure. (The parallels to our own time surely need no further spelling out.)

Systematic Deviation

It was against this background, in 1899, that Kautsky entered the fray against the “revisionist” Eduard Bernstein, who argued that a good deal of Marx’s analysis of capitalism was no longer valid. At this stage, Kautsky was arguing for Marxist orthodoxy and against the opportunism that flowed from Bernstein’s ideas.

But, as Lenin explains in chapter 6 of “State and Revolution,” something vital is missing from Kautsky’s argument: Far from defending Marx and Engels’ conclusion about the need to smash the state, Kautsky simply avoided the issue, merely saying, “We can quite safely leave the solution of the problems of the proletarian dictatorship to the future.”

“This,” Lenin fumes, “is not a polemic against Bernstein but, in essence, a concession to him, a surrender to opportunism, for at present the opportunists ask nothing better than to ‘leave to the future’ all fundamental questions of the tasks of the proletarian revolution.”

Lenin next considers Kautsky’s book “The Social Revolution” (1902), in which, again, Kautsky takes up his pen against opportunism. Here, too, Lenin finds that Kautsky “speaks of winning state power—and no more; that is, he has chosen a formula which makes a concession to the opportunists, inasmuch as it admits the possibility of seizing power without destroying the state machine.”

A common theme begins to emerge: While declaring his hostility to opportunism, Kautsky remains silent on the crucial question of state power—which has the effect, as Lenin says, of ceding vital ground to the opportunists.

This may at first seem a fairly minor sin, but remember the historical context described above. For a would-be defender of Marxism in an era of ever-increasing opportunism, the question of state power was one of the worst possible places to allow a breach in the wall.

Kautsky’s silence on this point is even more troubling in “The Road to Power” (1909)—“the last and best of Kautsky’s works against the opportunists,” as Lenin puts it. Lenin notes that this book is a “big step forward” compared to its predecessors, since it deals not merely with theoretical issues or the generalized tasks of the social revolution, but rather “deals with the concrete conditions that compel us to recognize that the ‘era of revolutions’ is setting in.”

Yet even here—even in a book that declares itself to be an analysis of “the political revolution” and declares that the “era of revolutions” is already upon us—Kautsky declined to be drawn on the question of state power. In Lenin’s words, “he completely avoided the topic.”

Kautsky Makes His Opportunism Explicit

So far, Lenin has traced Kautsky’s “systematic deviation towards opportunism” (as he phrases it in the book’s preface) primarily by noting what Kautsky left unsaid in each case. But after “The Road to Power,” as Lenin says, “[t]hese evasions of the question, these omissions and equivocations, inevitably added up to that complete swing-over to opportunism with which we shall now have to deal.”

This brings Lenin to the final stage of his discussion: A survey of the controversy between Kautsky and the Dutch socialist Anton Pannekoek, which unfolded in the pages of Die neue Zeit in 1912. And here, at last, Kautsky makes explicit what he has until now left unsaid.

As part of his response to Pannekoek’s advocacy of the view that one of the tasks of the proletarian revolution is to smash the capitalist state, Kautsky writes, “Up to now, the antithesis between the Social Democrats [i.e., the Marxists] and the anarchists has been that the former wished to win the state power while the latter wished to destroy it. Pannekoek wants to do both.”

Actually, as Lenin points out, both Marxists and anarchists call for the smashing of the capitalist state, though there are fundamental differences between the two camps. It is worth quoting him at length on this point:

The distinction between Marxists and the anarchists is this:

(1) The former, while aiming at the complete abolition of the state, recognize that this aim can only be achieved after classes have been abolished by the socialist revolution, as the result of the establishment of socialism, which leads to the withering away of the state. The latter want to abolish the state completely overnight, not understanding the conditions under which the state can be abolished.

(2) The former recognize that after the proletariat has won political power it must completely destroy the old state machine and replace it by a new one consisting of an organization of the armed workers, after the type of the Commune. The latter, while insisting on the destruction of the state machine, have a very vague idea of what the proletariat will put in its place and how it will use its revolutionary power. The anarchists even deny that the revolutionary proletariat should use the state power, they reject its revolutionary dictatorship.

(3) The former demand that the proletariat be trained for revolution by utilizing the present state. The anarchists reject this.

Clearly, however, Kautsky wishes to place the “Social Democrats” in neither camp.

Lenin observes: “Kautsky abandons Marxism for the opportunist camp, for this destruction of the state machine which is utterly unacceptable to the opportunists, completely disappears from his argument, and leaves a loophole for them in that ‘conquest’ may be interpreted as the simple acquisition of a majority.”

Or, in Kautsky’s own words (as quoted by Lenin):

[N]ever, under no circumstances can it [that is, the proletarian victory over a hostile government] lead to the destruction of the state power; it can lead only to a certain shifting [Verschiebung] of the balance of forces within the state power…. The aim of our political struggle remains, as in the past, the conquest of state power by winning a majority in parliament and by raising parliament to the ranks of master of the government.

No Break in Lenin’s Thinking?

This, then, is the main thread of Lenin’s analysis: that Kautsky’s “complete swing-over to opportunism” was not a sudden change of heart, but rather the final stage in a process of “deviation” that had, by 1912, been under way for well over a decade.

Whether or not one is persuaded by Lenin’s account, it must be admitted that by 1917, his views of “the pre-1914 Kautsky,” of whom he had previously held such a high opinion, had gone through dramatic and fundamental changes.

At this point the changes were still quite recent. Less than a year before he completed “State and Revolution,” Lenin was still arguing along lines strikingly similar to Kautsky’s own.

As late as December 1916, he could write, “Socialists are in favor of utilizing the present state and its institutions in the struggle for the emancipation of the working class, maintaining also that the state should be used for a specific form of transition from capitalism to socialism” (emphasis added).

In other words, as late as the end of 1916, Lenin still shared Kautsky’s view that, once the working class was in power, “the [existing] state should be used” to bring about the transition from capitalism to socialism. But by the autumn of 1917, as we have seen, Lenin was arguing vociferously against this view, insisting that “after the proletariat has won political power it must completely destroy the old state machine and replace it by a new one consisting of an organization of the armed workers, after the type of the [Paris] Commune.” It was this latter, entirely new kind of state that would bring about the transition from capitalism to communism.

Shortly after writing these words, Lenin embarked upon the researches that would produce “State and Revolution.” In the process, his view of Kautsky clearly went through a radical transformation, affecting not just Lenin’s opinion of specific writings but his overall understanding of Kautsky as a Marxist.

For Lih to dismiss this fundamental shift as “no appreciable blip,” and to suggest that there was never a significant shift in Lenin’s attitude toward Kautsky’s prewar writings, is nothing short of willful blindness.

“How Well Karl Kautsky Wrote Eighteen Years Ago!”

As for the fact that Lenin continued, despite this profound reappraisal, to find value in many passages of Kautsky’s earlier works, this does not, as Lih would have us believe, prove that the reappraisal wasn’t so profound after all. It merely demonstrates Lenin’s capacity to divorce his opinion of a piece of writing from his views on the writer.

Take, for instance, Lenin’s treatment of G.V. Plekhanov, which in some ways is strikingly similar to his treatment of Kautsky.

Plekhanov had been extremely important in the development of Russian Marxism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. But, like Kautsky, he moved to the right and ultimately became a vocal supporter of the war effort (in his case on the side of the Entente powers). He was a bitter opponent of Lenin and the Bolsheviks from 1905 onward, and (among other “sins”) he enthusiastically encouraged the rumor that when Lenin returned to St. Petersburg in April 1917, he was secretly working for the German government as an agent provocateur.

While unhesitatingly characterizing Plekhanov, too, as a renegade, Lenin nonetheless continued to honor and praise his earlier writings, even going so far as to write, in 1921, that “you cannot hope to become a real, intelligent Communist without making a study—and I mean study—of all of Plekhanov’s philosophical writings, because nothing better has been written on Marxism anywhere in the world.”

Clearly, Lenin had no difficulty continuing to find things to admire in the writings of people he regarded as political traitors.

“A Lackey of the Bourgeoisie”

The last word should go to Lenin. In 1918, in response to Kautsky’s denunciation of the October Revolution, Lenin wrote a pamphlet called “The Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky,” in which he offered a beautifully succinct description of Kautsky’s brand of Marxism. May it serve as a standing rebuke of those who seek to rehabilitate Kautsky and his opportunist “road to power.”

Kautsky takes from Marxism what is acceptable to the liberals, to the bourgeoisie (the criticism of the Middle Ages, and the progressive historical role of capitalism and capitalist democracy in particular), and discards, passes over in silence, glosses over all that in Marxism which is unacceptable to the bourgeoisie (the revolutionary violence of the proletariat against the bourgeoisie for the latter’s destruction). That is why Kautsky, by virtue of his objective position and irrespective of what his subjective convictions may be, inevitably proves to be a lackey of the bourgeoisie.