NOTE: This is the second of three linked documents on Left Oppositionists in a Russian Prison. The brief introductory reading guide is here. The political introduction to the series of three is here. The final document –— the text from the imprisoned Left Oppositionists in the 1930s — is here.

In this article, historian Aleksandr Fokin, a researcher at Tyumen University and Chelyabinsk State University in Russia, provides an overview of his research project related to the booklets discovered two years ago in the Verkhneuralsk prison. We thank the author for his kind permission to publish this article and for the booklets he transcribed.

***

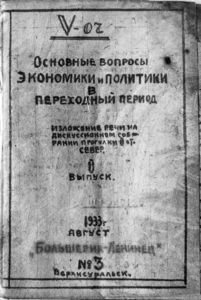

In early 2018, the Russian Federal Prison Service for the Chelyabinsk region, located in the capital city of the same name on the southern side of the Ural mountain range that creates the border between Europe and Asia, reported that during repairs to the Verkhneuralsk prison, a folder containing documents dating from 1932–3 was found under the floorboards of Cell No. 312. The documents — which came to be called “Notebooks of the Verkhneuralsk Political Prison”1GI translator’s note: The prison was run by the GPU (later the NKVD and KGB) during the Soviet period. Today, it continues to function, but as an ordinary prison. — were transferred to Chelyabinsk, where they were made available for study.

The growing number of projects involving oral histories, journals, letters, and other documents of interest to historical memory serves as a kind of alternative to academic historiography based on official documents, and these projects suggest a reevaluation of older attitudes toward archival evidence as the most important condition for an objective reconstruction of the past. In this new context, accidental findings like the Notebooks are of interest simply because new archives are so rare today. But do we really expect any revelations from the Notebooks compared to what we already know from the archival revolution of the 1990s?2GI translator’s note: This is a reference to the opening of the archives of the Soviet Communist Party and the Communist International, which had previously been mostly kept secret, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

The Notebooks remind us that the ideas of the so-called “school of totalitarianism”3GI translator’s note: This is a reference to the predominant historiographical interpretations by Western sovietologists during the Cold War period. regarding the omnipresent police control of the state did not reflect that even in the Stalinist Soviet Union, many people still thought and sometimes acted against the regime’s policies.

The Notebooks also show that the activities of the Left Opposition beginning in the late 1920s and into the 1930s have not yet been fully studied. This is due in part to the well-established stereotype that Trotsky’s supporters in the Soviet Union had been defeated in 1927, and therefore the attention of researchers shifted to their activities abroad.

Several contemporary researchers,4Broué; Gusev; Shabalin; Vakulenko drawing on both national and regional material, have challenged this view. They have shown that the activities of the Left Opposition continued under conditions of illegality, including in detention centers. But until recently, information about the activities of the Left Opposition within the Soviet Union in the 1930s was primarily indirect—such as through materials from the “Opposition Bulletin” and memoirs like the book by the famous Yugoslav communist Ante Ciliga, who spent time in various facilities as a political prisoner between 1930 and 1935. It is certainly feasible that several sources about the underground activities of the Left Opposition remain in state archives, but in most cases, researchers have not had access to them.

As Alexei Gusev points out, the political prisons of Verkhneuralsk, along with those of Yaroslavl and Suzdal, were the center of the Left Opposition’s ideological life after it was defeated by the repressive forces. Based on the memoir of Ante Ciliga, who came to the Verkhneuralsk prison in 1930, Gusev recounts the publication of the Bolshevik-Leninist journal in the prison:

“What a variety of opinions were presented here, what freedom in every article! What passion and openness in considering not only theoretical and abstract problems, but also the most current issues! Is it still possible to reform the system by peaceful means, or is an armed rebellion, a new revolution, required? Is Stalin a conscious or unconscious traitor? Is his policy one of reaction or counterrevolution? Is it possible to eliminate him simply by displacing the ruling elite, or is a real revolution necessary? All the articles were written with absolute freedom, without any concealment, their authors dotting their i’s, signing — oh, horror! — with their full names.”5Gusev, Stalinism through the Eyes of Trotskyists, p. 14

But if researchers had previously only built assumptions about the content of these publications, the Notebooks allow access to primary sources.

Chronologically, the Notebooks were written in 1932–33; they may be part of a larger collection, but earlier texts were either not preserved or have yet to be discovered. Since the discovery in Verkhneuralsk was made by accident during the repair of the cell, it is likely that other Notebooks will be found.

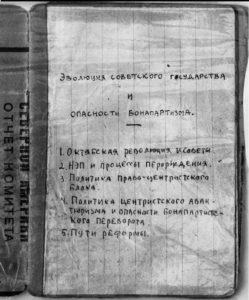

It should be noted that the specifics of how they were stored led to part of the Notebooks being severely damaged, and so it is impossible at this stage to determine the exact number of individual texts. Preliminarily, there are between 30 and 35 separate documents. Of those, about 27 are in a condition that allows for defining them with confidence and working with them. Among these, a sub-corpus of texts exists that the authors themselves designated as “The Crisis of the Revolution and the Tasks of the Proletariat.” This includes 11 separate Notebooks, two of which have been lost, but their titles and general content can be established from the list of all the documents.

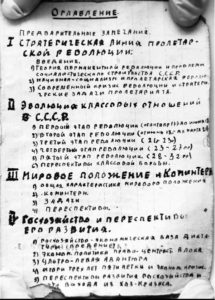

This sub-corpus “The Crisis of the Revolution and the Tasks of the Proletariat” includes the following texts:

- The Strategic Line of the Proletarian Revolution

- The Evolution of Class Relations in the USSR

- The World Situation and the Communist International

- The State Economy and the Prospects for its Development

- The Position of the Working Class

- Agriculture

- The Development of the Soviet State and the Danger of Bonapartism

- The Party

- Tactics and Tasks of the Leninist Opposition

- Program of Practical Suggestions

- Conclusion: Against Opportunism! For the Revolutionary Theory and Practice of Marx and Lenin!

This sub-corpus of texts is central to the Notebooks because it is the program of the Bolshevik-Leninists, in which they present their own views on the main aspects of politics in the country and the world. This very fact shows that even while they were imprisoned in 1932, the representatives of the Left Opposition did not consider their position lost and saw some prospects in the continuation of the political struggle against Stalinism.

Before the Notebooks were discovered, ideas about alternative forms of development in the Soviet Union, which were developed by representatives of the Left Opposition, could be found in Leon Trotsky’s materials and related publications, mainly in the Opposition Bulletin. It is worth mentioning that some issues of this publication also contain information from the Verkhneuralsk prison, which indicates that there may have been communication between prisoners and émigrés.

The basic idea from which the Bolshevik-Leninists built their program was the concept of permanent revolution. Trotsky updated this theory in 1929 in his book The Permanent Revolution, published the following year. The author, polemicizing with his critics, conceptualized this theory and opposed the Stalinist regime, calling it “national socialism.” Based on Trotsky’s work, in addition to quoting Lenin profusely, representatives of the Left Opposition in the Verkhneuralsk prison point out that even after the socialist revolution in Russia, the country continued to exist within the framework of the world division of labor. On this basis, they believed that the concept of building socialism in one country, which was established in the Soviet Union after the internal struggle of the party in the 1920s, was incorrect because it was impossible to meet national needs within a closed and isolated system.

Also important for the Bolshevik-Leninists was the idea that it was impossible to distinguish between domestic and foreign policy. They believed that the development of the class struggle within the country was linked closely to the general course of the international class struggle. Therefore, contradictions would build up in an isolated country, which would eventually lead to its death. In other words, the aim of the socialist state must not be to compete economically with the capitalist states, but to fight against the world bourgeoisie. It is necessary to bring the dictatorship of the proletariat to the international level, not to lock itself up in one country.

In this context, how the Left Opposition viewed the kolkhoz collective farm system is of interest. According to the “Bolshevik-Leninists, the Stalinist leadership — rather than solving the problems of the village — instead spearheaded the [kolkhoz] system, defining it a priori as a socialist system. While the official view on collective farms was distinguished by the desire to eliminate the social stratification of the village and eliminate the kulaks (rich peasants) as a class, the Notebooks instead posit that the collective farms are a cover for capitalist tendencies in which the rich peasants in the kolkhoz exploit the poor peasants. The Bolshevik-Leninists attributed this to the fact that “Stalinist centralism” needed social support but could not find it in the working class, and so the struggle against the kulaks was carried out. So, from the point of view of the Left Opposition, “Stalinist centralism” was creating collective farms in an effort to win the support of the average peasant.

According to the Bolshevik-Leninists, dependence on the average peasant in the kolkhoz was due to the conflicting interests of the bureaucracy and the working class. The theory of building socialism in one country responded to the social needs of the Soviet bureaucracy, which was becoming increasingly conservative in its aspirations for national rule and required the final consecration of the revolution. This is an interesting idea that implies the existence of different perceptive models of the October Revolution. The line implemented in the USSR presupposed the formation of the “founding myth,” in which the October Revolution was given a central place, since it had begun a new and true history. But this approach assumed that the Revolution was a process that had already been completed, the basis upon which the new Soviet society had been built. The alternative view of the Bolshevik-Leninists was that the Revolution could not be completed until final victory was achieved. In this case, the transformation of the Revolution into a myth is the defeat of the Revolution and the refusal to continue fighting. In this perception, the image of the Revolution goes from being a symbol of liberation to being an instrument of control by the political bureaucracy.

What, then, did the Bolshevik-Leninists propose to overcome the crisis? In 1932, they saw two paths for the development of the Soviet state. In one, they assumed there would be a bourgeois restoration in the Soviet Union, the instrument of which would be a violent coup d’état. However, it was not clear who, according to the Left Opposition, would be the initiator of this coup: either the regenerated Soviet bureaucracy, which would thus seek to consolidate its dominant position, or the remnants of the bourgeoisie, who could take advantage of the situation for revenge. But the reason for this coup d’état would be the Soviet leadership’s loss of the population’s support.

The second scenario involved a complete restoration of the dictatorship of the proletariat. Thus, the position of the Bolshevik-Leninists reflected the crisis of the idea of the dictatorship of the proletariat, which could end with the complete loss of power of the working class or with the restoration of the principles that had guided the first years of Soviet power. It is important to note that the struggle to restore the dictatorship of the proletariat was described as political — that is, the main means was reform and purification, not the violent seizure of power and the displacement of the leadership of the country.

Political changes were also to lead to changes in the economic sphere. The Bolshevik-Leninists believed that to maintain Soviet power, the peasants had to regain their confidence in the state, which had been undermined by adventurism in industry and agriculture. The state economy should not be based only on developed industry, but should also play the role of a link [smychka] between city and countryside. At the same time, the development of agriculture and industry had to be balanced. While recognizing the leading role of the state as regulator, they believed that market mechanisms should also be used in the face of planned regulation. Thus, in 1932, the Bolshevik-Leninists opposed Stalin’s policy of forced industrialization and collectivization by proposing a return to the New Economic Policy (NEP). Perhaps not in its entirety, but they saw the NEP as a way to preserve the unity of the workers and peasants. This view shows that the vision of the representatives of the Left Opposition as supporters of radical and large-scale industrialization is, in many ways, stereotypical. It is important to note that the return of the NEP involved only the economic component; market methods should be under the strict control of the proletariat. It was up to the party and the proletariat to set the boundaries of market relations. In such a situation, the peasants, being the subjects of economic relations, were perceived in the field of politics only as objects.

In this situation, Stalinist centralism, according to the Bolshevik-Leninists, contributed to the bourgeoisie’s desire for revenge by fighting against the Left Opposition. The Bolshevik-Leninists still saw the situation in the country as a field of struggle between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie. From this perspective, the main threat was not Stalin’s system: judging by the available documents, they did not see a long-term perspective for Stalin’s personal regime of power, although they perceived it as a certain world trend. The main threat they saw was the bourgeois Thermidor, for which national socialism was paving the way.

The analysis of the Bolshevik-Leninist position on the key problems of the country’s development raised an important question: how did the imprisoned authors of the Notebooks plan to begin reforming the Soviet system and thus avoid the revenge of the bourgeoisie? That, in turn, makes one wonder to whom the texts were addressed. Did the Bolshevik-Leninists see themselves as the revolutionaries of the early 20th century who, from prison, had made plans to overthrow the Tsarist regime? How much did they believe in the possibility of carrying out their own plans?

It seems possible to identify two motivations in the writing of the Notebooks. On the one hand, they played the role of “meeting place” for these particular prisoners in the Verkhneuralsk political detention center. Being in detention, under conditions of political defeat, these people were thus supported within a certain group that not only sought physical survival during their incarceration, but also saw a more significant reason for their existence. One could consider the work of writing the Notebooks as a tool to overcome the crisis of the Opposition. On the other hand, many of the prisoners had had the experience of going through the Tsarist prisons. Furthermore, the relative leniency toward political opponents in the early 1930s allowed the Bolshevik-Leninists to share their political program in the context of the crisis, both at home and abroad, which would also become relevant and serve as a basis for a return to the dictatorship of the proletariat and the construction of genuine socialism.

Bibliography

Вакуленко А. А. Политическая публицистика коммунистической оппозиции: 1929–1941 гг.: дисс… канд. ист. наук. Тюмень, 2009. [A.A. Vakulenko, “Political Journalism of the Communist Opposition: 1929–1941,” Dissertation, Tyumen University, 2009]

Гусев А. В. “Сталинизм глазами троцкистов: дискуссии о характере сталинского режима в среде левой коммунистической оппозиции в конце 1920-х – 1930-е гг.” // Политические и социальные аспекты истории сталинизма. Новые факты и интерпретации. Москва, 2015. С. 7–17. [А.V. Gusev, “Stalinism through the Eyes of the Trotskyites: Discussions of the Character of the Stalinist Regime among the Left-wing Communist Opposition in the Late 1920s–1930s.” In Political and Social Aspects of the History of Stalinism: New Facts and Interpretations (Moscow, 2015, pp. 7–17)]

Гусев А. В. Троцкистская оппозиция в конце 20-х – начале 30-х годов: дисс… канд. ист. наук. Москва, 1996. [А. V. Gusev, “Trotskyist Opposition in the Late 1920s–Early 1930s,” Dissertation, Moscow, 1995]

Шабалин В. В. Пейзаж после битвы. Из истории левой оппозиции на Урале. Пермь, 2003. [В. V. Shabalin, Landscape after the Battle: From the History of the Left Opposition in the Urals (Perm, 2003)]

Broué, Pierre, “Party Opposition to Stalin (1930–1932) and the First Moscow Trial,” In John W. Strong (ed.), Essays on Revolutionary Culture and Stalinism (Bloomington, IN: Slavica Publishers, 1990), 98–111.

Ciliga, Ante, Dix ans au pays du mensonge déconcertant (Paris, 1977) [Ante Ciliga, Ten Years in the Land of Disconcerting Lies (Paris, 1977)]

First published on May 3, 2020 in Spanish in Ideas de Izquierda.

Translation: Scott Cooper

Notes

| ↑1 | GI translator’s note: The prison was run by the GPU (later the NKVD and KGB) during the Soviet period. Today, it continues to function, but as an ordinary prison. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | GI translator’s note: This is a reference to the opening of the archives of the Soviet Communist Party and the Communist International, which had previously been mostly kept secret, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. |

| ↑3 | GI translator’s note: This is a reference to the predominant historiographical interpretations by Western sovietologists during the Cold War period. |

| ↑4 | Broué; Gusev; Shabalin; Vakulenko |

| ↑5 | Gusev, Stalinism through the Eyes of Trotskyists, p. 14 |