Photo credits: Karim Aït Adjedjou

The idea of running Anasse Kazib as a candidate for the French presidency began as a proposal during the debates within the NPA, an organization in which Révolution Permanente was a public current. After two campaigns in which the NPA ran Philippe Poutou as its candidate (2012 and 2017), it seemed obvious that the time had come to “pass the baton.” The NPA had established “no more than two candidacies” as a sort of principle when Olivier Besancenot and Philippe Poutou himself had publicly announced that Poutou would not run again.1Translator’s note: Philippe Poutou is a former autoworker and union leader. Olivier Besancenot is a founder of the NPA and its main spokesperson. In addition, there was a new generation of activists who emerged from the wave of class struggle that began in 2016; they came from the labor movement and popular uprisings such as that of the Yellow Vests, as well as from the anti-racist, feminist, LGBTQ+, and environmental movements.

Kazib had the advantage of perfectly embodying this phenomenon. A 34-year-old railway worker from a family of Moroccan immigrants, he had become politicized in the movement against changing the French Labor Code in 2016,2Translator’s note: Beginning in March 2016, a huge movement erupted in France — with protests, strikes, and marches — in opposition to the Socialist Party’s proposed labor law reforms, which would lengthen the work week and make it easier for employers to fire workers. in the wake of which he joined Révolution Permanente and the NPA the next year. He had been part of all the fights during Emmanuel Macron’s term as French president. In the massive 2018 strike of railway workers against the railway reform, he was a visible leader of the “Intergares,” a collective of unionized and nonunionized railway workers who pushed to go beyond the slowdown strategy imposed by the union leaderships. He was active in the movement against pension reform, helped lead the coordinating committee established with RATP and SNCF workers,3Translator’s note: The RATP and SNCF are the public transit operator for Paris and environs, both with light rail and buses, and France’s public passenger railroad company, respectively. and was connected with the victorious strike of ONET workers who clean the train stations, the Yellow Vests, and Pôle Saint-Lazare.4Translator’s note: Pôle Saint-Lazare brought together thousands of militants from the labor movement and working-class neighborhoods to demonstrate alongside the Yellow Vests. He had close links with the anti-racist movement, the struggle against police violence, and so on. He had also made his presence known on television, as a commentator on Les Grandes Gueules podcast for two years, and through his many confrontations with bourgeois politicians around Macron’s various counterreforms.

The wave of strikes that began in 2009 had seen the emergence of figures from our class such as the trade unionists Xavier Mathieu and Mickaël Wamen. It soon became obvious that Kazib, along with Assa Traoré5Translator’s note: Assa Traoré is a well-known anti-racism activist in France and a leader of the Committee for Justice and Truth for Adama, named for her half brother Adama Traoré, who died in French police custody. and some people from the Yellow Vests, were the new figures of 2016 and beyond. In this respect, proposing that he be a presidential candidate marked a change in orientation, breaking with an adaptation to La France Insoumise,6Translator’s note: La France Insoumise (LFI, Unbowed France or Unsubmissive France) is a social-democratic populist party founded in 2016. which had been expressed in particular in the regional elections, in favor of an openly revolutionary candidacy that would represent what had been achieved in the particularly valuable class struggles that France had just gone through.

The NPA leaders, unfortunately, had the opposite view. In a party in which all debates are public, they treated the proposal for Kazib’s candidacy as an “attack on the party.” It served as a pretext for pushing the 300 militants and sympathizers of Révolution Permanente out the door two months later. They then made the conservative choice of a third Poutou candidacy, which no one wanted — first and foremost Poutou himself. That move was supported by only 52 percent of the delegates at the National Conference, despite that excluding Révolution Permanente from the ballot left no alternative candidate.

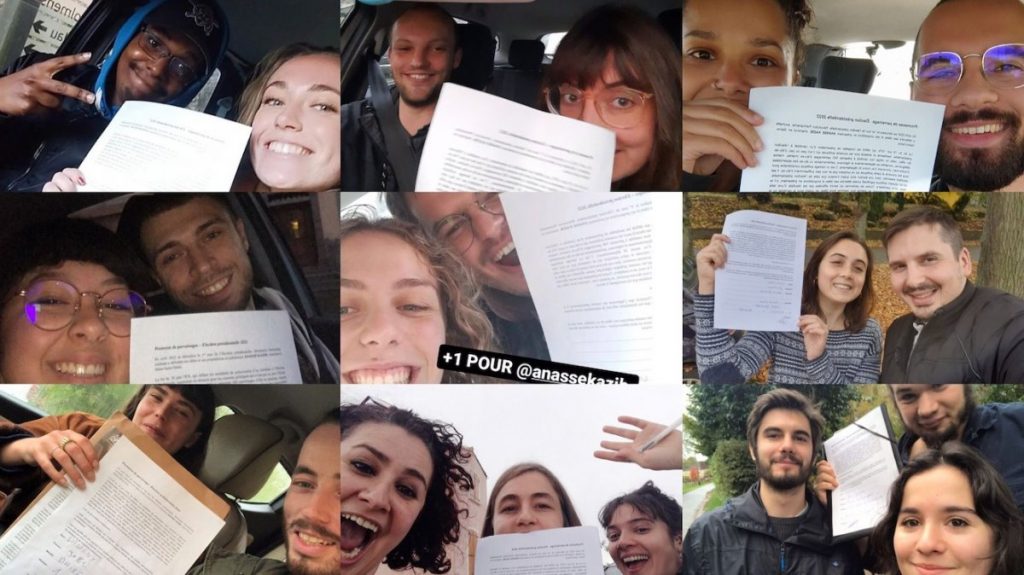

Once we were kicked out of the NPA, we decided to formalize the candidacy of Kazib, convinced that it would be a profound step to take that would carry the seed of a necessary revitalization of the Far Left in France, which had almost universally missed the boat with the wave of struggles that began in 2016. We knew that obtaining 500 sponsorships7Translator’s note: French election law requires that presidential candidates, to gain first-round ballot access, secure 500 “sponsorships” from mayors, members of parliament, and regional councillors from 30 different departments (which are like counties) in the country — roughly like the petitioning often required to secure ballot access in the United States. These are not endorsements of the candidate, but statements in support of the democratic right of the candidate to run. would be a tough hill to climb for a current that had just become an independent organization and that, moreover, would be running a young worker from an immigrant background in a presidential campaign monopolized by xenophobia and racism. We determined, however, that it would be worth the effort and that it would be a battle we ought to fight.

A Subversive Campaign That Openly Confronted the Far Right

The campaign officially kicked off in mid-October, with a meeting that brought together nearly 500 people in an enthusiastic rally with many prominent supporters. The next day, the Far Right launched a campaign denouncing the absence of the French tricolor flag in the room, then trended on Twitter with the hashtag #AnasseRemigration. In more than 60 years of the Far Left’s participation in French elections, there have never been tricolor flags in the meetings — and it had never caused a scandal. Clearly, it was Kazib’s status as a candidate of postcolonial immigration that made this time different.

A torrent of hatred was unleashed. Kazib was accused of “spitting on the French flag” and “hating France.” There were threats to “hang him” with the tricolor and to “bleed him out” — and his family — “in the halal way.” This offensive continued the next day on the set of Touche pas à mon poste8Translator’s note: Touche pas à mon poste! (TPMP) is a live talk show on French television broadcast each weeknight and rebroadcast throughout the daytime hours. (his only invitation to appear on TV until February), with the show turning into a trial against the candidate, described as the “anti-Zemmour,” around this same flag narrative.9Translator’s note: Eric Zemmour is a far-right media personality in France who is running for president on an openly racist and xenophobic platform.

A few months later, Kazib was asked to participate as part of the Debates at the Sorbonne series to which other candidates were invited. The Natifs (Natives), the new name of a far-right group known as Génération identitaire (Identitarian Generation) that was forced to dissolve in March 2021, plastered the Latin Quarter of Paris with a poster denouncing the invitation, describing Kazib as a candidate “0 percent French, 100 percent ‘woke,’ 100 percent Islamist.” Faced with the threat that the Natifs would attempt to disrupt the conference, a call went out on social media for solidarity around the hashtag #AnasseSorbonne. Nearly 500 people gathered at the Place du Panthéon, in front of the Sorbonne building that was supposed to host the conference. Ultimately, the meeting was held outside, well secured thanks to an outpouring of solidarity from several anti-fascist collectives.

Throughout the campaign, the Far Right never let up on Kazib, spreading “fake news” and insults about him and making continual threats. It was an offensive against the Far Left rarely seen in France, one that expressed the tremendously subversive nature of the Kazib candidacy as articulating the centrality of the working class and alliance with the struggles of all the oppressed (anti-racists, LGBTQ+, feminists, etc.) in the service of a revolutionary perspective. It was no concession by Marxism to “wokeist” or “decolonial” tendencies, as some reactionary politicians and journalists would have us believe, but instead constituted a return to the best of the revolutionary tradition. In a period marked by a radicalization of the Right, this alternative campaign was greeted by more than 250 intellectuals, artists, and political, trade union, and anti-racist activists, who insisted that Kazib’s absence from the election would be a “defeat.”

Dynamic, Militant Campaign Lays the Foundation for a “Bloc of Resistance”

Interest in the campaign was striking among workers, youth, and residents of working-class neighborhoods throughout the six months of campaigning. Attendance at rallies and meetings — even though they took place several months before the elections themselves — testify to this: 500 people in Paris, 350 in Toulouse, 400 at the Institute of Political Studies in Bordeaux, 400 at the University of Paris 8, and 250 in Marseille, to name only the largest turnouts. Driven by the candidate’s charisma and fiery speech, these figures speak to a very militant campaign that involved more than 500 people, across the country, who helped organize rallies and public meetings, distributed leaflets, put up posters, and went on the road to meet public officials to encourage them to become sponsors.

The campaign won the support of entire teams of industrial and service workers and hundreds of students that these events brought together. The Paris meeting that launched the campaign opened with a list of the sectors present in the room, to thunderous applause:

We are proud to see delegations from different sectors of the working class that have kept society running during the pandemic: the Neuhauser workers, who forced their boss to redistribute food during the pandemic; the Transdev strikers; the Infrapôle agents on strike for seven months; the SKF workers in Avallon fighting against layoffs; workers from Onet; the CSP Montreuil activists who were recently attacked. At their side are dozens of workers from the RATP and the SNCF. There are refinery workers, and teachers, and students from Paris 1, Paris 5, Paris 8, and Nanterre, as well as several groups of families of victims of police violence.

All this reveals a campaign that was not undertaken simply so we could say we’d done so, but showed itself capable of speaking to and mobilizing those who have been engaged in struggle over the past five years. Youcef Brakni, an activist in the working-class neighborhoods, keenly described this dynamic at a meeting in the Paris 8th arrondissement when he declared, “With these meetings and these tours, we are building a bloc of resistance for the future.” This “bloc” is, for us, a fundamental achievement of these past months, and it will have to broaden to prepare for a counteroffensive against the coming attacks of the next government and the Far Right.

We also saw this dynamic unfold among the many public figures who supported the campaign in many ways, including Adrien Cornet, from the CGT trade union at the Grandpuits oil refinery; well-known activists from the Adama Committee, such as Assa Traoré and Almamy Kanouté; and the transfeminist activist Sasha Yaropolskaya. Some of them, along with many local workers and activists, committed themselves to the campaign by taking part in meetings from the podium and by working together in a support committee. Others came out to support Kazib from the offensive waged against him, spreading the word about our campaign, denouncing the attacks, signing open letters, and speaking out with their own words of solidarity, as did noted economist and philosopher Frederic Lordon, actor Adèle Haenel, and writer Sandra Lucbert.

The Anti-democratic Workings of the Regime Revealed

Even with all its momentum, though, the campaign confronted many hurdles. The first one was obviously the high bar of obtaining 500 sponsorships from elected officials, a system that has revealed its complete bankruptcy this year, and whose anti-democratic character was amplified in our case.

Despite an immense effort, including meetings with more than 7,000 mayors and other officials, the campaign faced pressure from above, blackmail for payoffs, and other difficulties. There were mayors who slammed the door as soon as they saw Kazib’s photo on his statement of principles or heard his name. Others, rather embarrassedly, told us they could hardly explain to their constituents sponsoring a candidate “like Anasse” when in their village the Far Right was scoring high in every election. These pressures were reinforced by the Far Right’s effort to undermine our campaign, such as when a mayor promised his sponsorship but later informed us that he had been attacked by his first deputy for having done so and subsequently had to lodge a complaint with the police!

Nor did the banks make life easy for us. Throughout the campaign, we had to fight to open a campaign bank account that would enable us to collect donations by credit or debit card. Most banks we contacted just refused to open an account; those that opened an account wouldn’t let us use that service, which is essential to fundraising. More generally, money was a real obstacle to waging the campaign, with lots of expenses for gas and room rentals. Like all the campaigns that failed to obtain 500 sponsorships, we are ineligible for any reimbursement, which leaves all these significant costs for our new organization to handle.10Translator’s note: Political parties in France receive some state funding in the form of what are called “fractions,” which depend on the proportion of the vote a party won in the last round of parliamentary elections and the actual number of seats the party wins in parliament. This funding represents about 40 percent of party funds across the board. This is the “reimbursement” to which the authors are referring.

Did you know Left Voice has a podcast? Listen to All That’s Left on Spotify and Apple Podcasts.

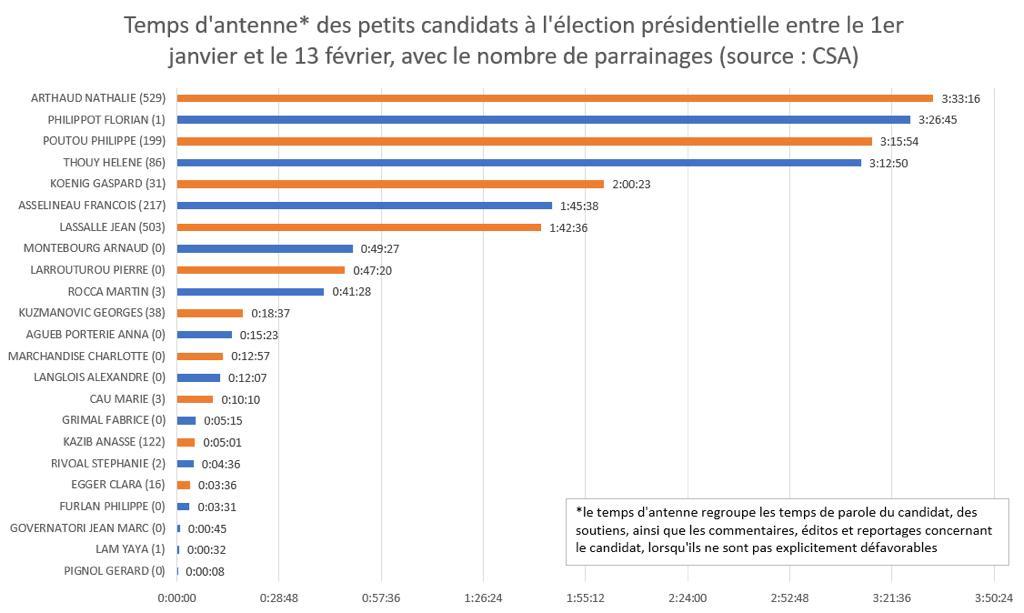

The explicit media blackout of Kazib’s campaign was also a major obstacle. From January 1 to February 13, our candidate was able to speak on television and radio for only three minutes, far less than all the other candidates. When the Constitutional Council of France published its tracking of sponsorships on February 15, several television channels went further — simply omitting Kazib from the counts they were showing of validated sponsorships and including candidates with far fewer, such as Hélène Thouy and Christiane Taubira.11Translator’s note: Hélène Thouy of the Animalist Party campaigned solely around animal rights. Christiane Taubira won the so-called French People’s Primary to stand as a “unity Left” candidate in the elections; she had 73 sponsorships at the moment in question. She was minister of Justice in the Socialist Party government of President François Hollande from 2012 to 2106. This open boycott gave birth to the hashtag #OùEstAnasse (Where is Anasse?), a playful way of pointing out and denouncing Kazib’s “invisibilization” by the mainstream media. Neither a complaint to the French media regulatory authority nor to the Council of State brought an end to the blackout.

Finally, the campaign ended with what was the last tool available to the regime to pressure our candidacy: Kazib was summoned by the police after the public prosecutor’s office investigated the Sorbonne rally. Quite incredibly, the prosecutor has decided to charge Kazib with holding an unauthorized rally, and he must appear in court on May 18. Meanwhile, not a single activist from the Far Right who threatened him has had anything to worry about.

Against All Odds: 161 Sponsorships

The subversive nature of our candidacy, the media blackout, and all these other elements obviously had a direct impact on obtaining sponsorships. It became an insurmountable obstacle for a first-time candidate, little known by mayors, running from an organization that is also new. At the beginning of February, half the 250 sponsorship promises we had collected could not be converted into the real thing. Some officials argued that they never saw us in the media or in the polls, and so had decided to sponsor another candidate. Others gave in to pressure from institutions or their constituents. Still others consciously chose to help better-known candidates, many of whom were parading their fear that they wouldn’t meet the 500-signature threshold.

With momentum slowed by the pandemic and an insufficient base of sponsorships, it became more and more difficult for us to convince new officials that it was worthwhile to sponsor us and that we could still make the cut. On top of that, no one else lifted a finger to help. In fact, we have not received any help from anyone — obviously not from so-called liberal democrats, but also not from the organizations of the institutional Left either, which, for example, have enabled the NPA to obtain almost 250 new sponsorships just in the last week, in the name of what they the call in their communiqué “political solidarity.”

Given this, obtaining 161 sponsorships was no small feat, and it’s something we are very proud of. We knew how difficult it was going to be to run a working-class, immigrant, and revolutionary candidate in the presidential election. But we made the conscious choice to wage the campaign and expose the anti-democratic character of this system. The journey we’ve taken puts the lie to the claim that anyone can run for office. Through its parties, its media, and its justice system, the regime ultimately decides who can and who cannot be a candidate.

A Vote for Class Independence

Despite our many disagreements with the presidential candidates of Lutte Ouvrière (LO)12Translator’s note: Lutte Ouvrière (Workers’ Struggle) is a French Trotskyist party that traces its origins back to 1939. and the NPA — as recent statements by LO’s Nathalie Arthaud concerning women wearing headscarves, and Poutou’s in favor of sanctions against Russia, further illustrate — we recognize them as candidates of our class who are running on programs of revolutionary transformation of the society. In this, they differ from the candidacy of Jean-Luc Mélenchon13Translator’s note: Mélenchon is the founder of La France Insoumise and the party’s presidential candidate., who has no intention of building and deepening the class struggle fights that Macron has had to face during his five-year term (Yellow Vests, pension reforms, anti-racist mobilization) but instead aims to channel them onto an institutional terrain. Of course, there are those who will vote for the LFI candidate as the “lesser evil,” given the neoliberalism and xenophobia of the Right and Far Right, but our view is that now, in a period of exacerbation of crisis, is the time to prepare the working class and oppressed to fight.

As we see it, this struggle can be carried out only on the basis of complete independence from big business. Mélenchon, though, calls on us to work with the bosses. We cannot have any illusions in such a policy of conciliation. Counting on a transformation of society through institutional means is a dead end; the failures in our neighbors — Syriza in Greece and Podemos in the Spanish State — are a reminder.

A New Revolutionary Organization

War returned to Europe just as our campaign came to an end, and it is becoming clear that the contradictions of the capitalist system are leading us toward ever more brutality, authoritarianism, and misery for the working class and oppressed. The coming five-year period, most likely with Macron still president, will be very difficult. Macron has already promised to raise the retirement age, establish new conditions for unemployment and underemployment benefits, sharpen the offensive against immigration and working-class neighborhoods, and smash the national education system. In an international context of growing crises and wars, and with the presidential election being held as demonstrations break out in Corsica14Translator’s note: The large Mediterranean island of Corsica, with a population just shy of 350,000 people (mostly a national minority, Corsicans, with their own language), is a “territorial collectivity” of France (one of the country’s specific administrative divisions). It became a colony of France in the mid-18th century and has been occupied ever since. Last month, demonstrations broke out on the island after a leader of the Corsican independence movement who was imprisoned in 1998 was beaten by another inmate and left in a coma. and tensions in France over wages and price increases grow, class struggle will erupt sooner rather than later.

In this context, our criticism of the “strategic vote”15Translator’s note: The vote utile (literally “useful vote”) is the rough equivalent of voting for the “lesser evil” in the United States. Here, it is being used to refer to votes for Mélenchon of the LFI. is the opposite of a call for passivity. We are calling for a critical vote for the candidates of the NPA and Lutte Ouvrière, but at the same time we are convinced that the Far Left needs a revolutionary refoundation after years of its routinism, its lack of initiative in the class struggle, its adaptation to the trade union bureaucracy, and its conservatism in response to the new generation of workers and activists. This is why Kazib will run in June’s legislative elections in a district of the Paris suburb of Seine-Saint-Denis, and the day after the vote we will launch the founding of a new revolutionary organization.

Through this process, we want to begin — with many of those who worked with us in the presidential campaign — to build an instrument that can be used by workers, youth, and working-class neighborhoods to wage a social revolution, one that will put an end to capitalism, patriarchy, racism, and the destruction of the planet. We envision an organization that can intervene in the next explosions of the class struggle — which may not be long in coming, especially if the scenario of a second Macron five-year term comes to pass. The presidential elections are only temporary for us; ours is a longer-term perspective that we will be discussing with all the supporters of the Kazib campaign in the coming weeks.

First published in French on March 20 in RP Dimanche.

Translation by Scott Cooper

Notes

| ↑1 | Translator’s note: Philippe Poutou is a former autoworker and union leader. Olivier Besancenot is a founder of the NPA and its main spokesperson. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Translator’s note: Beginning in March 2016, a huge movement erupted in France — with protests, strikes, and marches — in opposition to the Socialist Party’s proposed labor law reforms, which would lengthen the work week and make it easier for employers to fire workers. |

| ↑3 | Translator’s note: The RATP and SNCF are the public transit operator for Paris and environs, both with light rail and buses, and France’s public passenger railroad company, respectively. |

| ↑4 | Translator’s note: Pôle Saint-Lazare brought together thousands of militants from the labor movement and working-class neighborhoods to demonstrate alongside the Yellow Vests. |

| ↑5 | Translator’s note: Assa Traoré is a well-known anti-racism activist in France and a leader of the Committee for Justice and Truth for Adama, named for her half brother Adama Traoré, who died in French police custody. |

| ↑6 | Translator’s note: La France Insoumise (LFI, Unbowed France or Unsubmissive France) is a social-democratic populist party founded in 2016. |

| ↑7 | Translator’s note: French election law requires that presidential candidates, to gain first-round ballot access, secure 500 “sponsorships” from mayors, members of parliament, and regional councillors from 30 different departments (which are like counties) in the country — roughly like the petitioning often required to secure ballot access in the United States. These are not endorsements of the candidate, but statements in support of the democratic right of the candidate to run. |

| ↑8 | Translator’s note: Touche pas à mon poste! (TPMP) is a live talk show on French television broadcast each weeknight and rebroadcast throughout the daytime hours. |

| ↑9 | Translator’s note: Eric Zemmour is a far-right media personality in France who is running for president on an openly racist and xenophobic platform. |

| ↑10 | Translator’s note: Political parties in France receive some state funding in the form of what are called “fractions,” which depend on the proportion of the vote a party won in the last round of parliamentary elections and the actual number of seats the party wins in parliament. This funding represents about 40 percent of party funds across the board. This is the “reimbursement” to which the authors are referring. |

| ↑11 | Translator’s note: Hélène Thouy of the Animalist Party campaigned solely around animal rights. Christiane Taubira won the so-called French People’s Primary to stand as a “unity Left” candidate in the elections; she had 73 sponsorships at the moment in question. She was minister of Justice in the Socialist Party government of President François Hollande from 2012 to 2106. |

| ↑12 | Translator’s note: Lutte Ouvrière (Workers’ Struggle) is a French Trotskyist party that traces its origins back to 1939. |

| ↑13 | Translator’s note: Mélenchon is the founder of La France Insoumise and the party’s presidential candidate. |

| ↑14 | Translator’s note: The large Mediterranean island of Corsica, with a population just shy of 350,000 people (mostly a national minority, Corsicans, with their own language), is a “territorial collectivity” of France (one of the country’s specific administrative divisions). It became a colony of France in the mid-18th century and has been occupied ever since. Last month, demonstrations broke out on the island after a leader of the Corsican independence movement who was imprisoned in 1998 was beaten by another inmate and left in a coma. |

| ↑15 | Translator’s note: The vote utile (literally “useful vote”) is the rough equivalent of voting for the “lesser evil” in the United States. Here, it is being used to refer to votes for Mélenchon of the LFI. |